Transcription

Business and the Liberal Arts:integrating professional and liberal educationReport of a Symposium on the Liberal Arts and Business, May 2007By David C. Paris

Copyright 2007 Council of Independent CollegesThe Council of Independent Colleges is an association of more than 570 independent liberal arts colleges anduniversities and 50 higher education affiliates and organizations that work together to strengthen college anduniversity leadership, sustain high-quality education, and enhance private higher education’s contributions tosociety. To fulfill this mission, CIC provides its members with skills, tools, and knowledge that address aspects ofleadership, financial management and performance, academic quality, and institutional visibility. The Council isheadquartered at One Dupont Circle in Washington, DC.

Table of ContentsAcknowledgements:6Introduction:7Opening Remarks:9Program Profiles:12Richard Ekman, President, Council of Independent CollegesNew Challenges and Opportunities for the Liberal ArtsRyan LaHurd, President, James S. Kemper Foundation“Blending” the Liberal Arts into Business ProgramsBirmingham-Southern College: The Great Writers and BusinessStephen Craft, Dean of Business Programs and Elton B. StephensProfessor of Marketing12Dominican University: Liberal Arts and Sciences SeminarsDaniel Condon, Professor of Economics13Franklin Pierce University: Bringing Business into the Liberal ArtsKelly Kilcrease, Associate Professor of Management and Chair,Business Administration Division14Mars Hill College: “Commons” CoursesPaul Smith, Associate Professor of Business Administrationand Chair, Department of Business Administration16Shenandoah University: An Individualized Bachelor’sin Business Administration (iBBA)John Winn, Associate Professor of Business Law16Thomas College: E-Portfolio Model and Internship ProgramJames Libby, Associate Professor of Business Administration17Ursinus College: Business as Part of a Liberal Arts Majorwith an Emphasis on WritingAndrew Economopoulos, Professor of Business and Economics18Southwestern University: A Liberal Arts ModelMary Grace Neville, Assistant Professor of Economics and Business19the council of independent colleges

Program Profiles:20Preparation for Business Beyond the Business MajorHanover College: “Camp 3”—Abolishing the Business Major(and Living to Tell the Story)Robyne Hart, Director, Center for Business Preparation20Ripon College: “Collaboration, not Conflict”—Building a BusinessProgram through the Liberal ArtsMary Avery, Associate Professor of Business Administration21University of Evansville: “iBASE,” A Certificate without a MajorRay Lutgring, Associate Professor, Department of Chemistryand Director, Honors Program22Remarks:23Program Profiles:27Keynote Address by Rick Stephens,Vice President for Human Resources,Boeing Corporation and Member, Secretary of Education Spellings’Commission on the Future of Higher Education“Outreach” Within and Beyond the CampusUniversity of Puget Sound: Recruiting Students and Building Tiesto the Business Community—The Business Leadership ProgramJim McCullough, George Frederick Jewett Professor of Business and Leadershipand Director, School of Business Leadership27Sweet Briar College: Contacting and Contracting On and Off CampusThomas Loftus, Associate Professor of Business and Economics28University of St. Thomas: Business Faculty Teaching in29Liberal Arts ProgramsMichele Simms, Associate Professor, Cameron School of BusinessEmory & Henry College: Reaching Out on Campusand Through Service LearningScott Ambrose, Chair and Assistant Professor of BusinessProgram Profiles:3031Using a Thematic Focus to Integrate Business and the Liberal ArtsChristian Brothers University: Ethics, Service, and PersonalDevelopment as the Core of the ProgramBevalee Pray, Associate Professor of Business Report of 2007 Symposium on the Liberal Arts and Business31

College of St. Catherine: “Sales” and Ethics as a Focus forBusiness/Liberal Arts StudyLynn Schleeter, Director, Center for Sales Innovation,Business Administration Department32Hendrix College: Entrepreneurship as a FocusS. Keith Berry, Professor of Economics and Business33Manchester College: “Innovation” as a Theme on Campus and BeyondJames Falkiner, Mark E. Johnston Professor of Entrepreneurship34Oklahoma City University: Globalization and the Liberal ArtsHossein S. Shafa, James Burwell Endowed Chair of Managementand Professor of International Business Finance35Program Profiles:36Programs in the MakingThe College of Idaho: A Paradigm for IntegrationJason Schweizer, Director, Department of Business and Accounting36Augustana College: Devising a New Curriculum,Bringing Together the Two “Sides”Craig VanSandt, Assistant Professor of Business Administration37Bridgewater College: Integration through Grant-SupportedProgramming across the CurriculumBetty Hoge, Assistant Professor of Economics and Business Administration38University of Richmond: A New Center for Innovation and EntrepreneurshipJeffrey Harrison, Professor of Business39Future Research:40End Notes:43Short Profiles of Participating Institutions45Participants List49Remarks by Anne Colby, Senior Scholar, Carnegie Foundationfor the Advancement of TeachingLessons Learned and Next Stepsthe council of independent colleges

AcknowledgementsThe Council of Independent Colleges is grateful to the James S. Kemper Foundation for itsgenerous support of the “Symposium on Business and the Liberal Arts: Integrating Professionaland Liberal Education” that was held in Chicago in May 2007. Not only did the Foundationprovide financial support, but its president, Ryan LaHurd, participated. His remarks were a valuablecomponent of the symposium.The 2007 symposium was the second in a series supported by Kemper and convened by CICout of concern that the proportion of students graduating with degrees in the liberal arts has beendeclining as preprofessional and technical programs have expanded and the quality of one sideor the other, or both, would suffer. During the meeting, faculty members and administrators from24 colleges and universities came together to address issues such as: How should our institutionsrespond to these shifts? What innovative approaches to these challenges might work best? Whatcan or should we do to combine liberal arts and preprofessional education? Based on thosediscussions, this report focuses on some programmatic examples of how studies in business and theliberal arts can be successfully combined, and it highlights some of the strategies that independentliberal arts colleges and universities are employing to respond to these concerns.The first “Symposium on the Liberal Arts and Business” in 2003 brought together ten corporateleaders and ten college and university presidents to address the connections between liberal artseducation and professional leadership, particularly in business. The discussions at the meetingwere summarized in the volume, Report of a Symposium on the Liberal Arts and Business, edited byThomas Flynn and published by CIC in 2004. Print copies of this publication are available freeof charge and may be ordered from CIC. A PDF version is available on CIC’s website at www.cic.edu/publications/books reports/index.asp.Thanks should be given to CIC Senior Advisor David Paris, who is also the Leonard C.Ferguson Professor of Government at Hamilton College, for leading the 2007 symposium andpreparing this report. CIC is grateful for the encouragement and support of Douglas Viehland,executive director of the Association of Collegiate Business Schools and Programs. For theirwork on the program and this publication, CIC also thanks Frederik Ohles, formerly CIC seniorvice president and currently president of Nebraska Wesleyan University, Thomas Hellie, formerpresident of the Kemper Foundation and now president of Linfield College, and CIC staff membersStephen Gibson, director of projects, and Laura Wilcox, vice president for communications.Finally, we owe special thanks to the speakers, college administrators, and faculty members whoparticipated in this symposium and shared their work and the ideas that made the event and thispublication possible.Richard EkmanPresidentCouncil of Independent CollegesWashington, DC Report of 2007 Symposium on the Liberal Arts and Business

introductionWith the pace of economic change and global competition constantly accelerating, theeducational requirements for most jobs are increasing. The market is demanding ever-higherlevels of problem-solving and communication skills, as well as the capacity for teamwork andadaptability to rapidly changing conditions. It is now widely recognized that some postsecondaryeducation is becoming the minimum standard for entry into well-paying jobs, and the proportion ofthe population entering postsecondary programs is increasing worldwide.As more students elect to attend college in response to these economic pressures, the kindsof programs they wish to pursue have shifted dramatically. Nationally, the proportion of studentsgraduating with degrees in the liberal arts has been declining as programs offering preprofessionaland technical degrees have expanded. These shifts reflect student demands for programs that are“practical” or “relevant” and degrees that have some clear instrumental value. Although employerscontinue to emphasize the importance of a well-rounded education and broad skill development,students also want access to more specific, job-oriented educational programs.These changes represent a challenge to the country’s approximately 600 smaller private collegesand universities that view liberal education as the foundation or core of their mission. How shouldour institutions respond to these shifts? What innovative approaches to these challenges mightwork? What can or should we do to combine liberal and preprofessional education?The Council of Independent Colleges (CIC), which is the national service organization forthe country’s small and mid-sized private colleges and universities, first addressed these challengesin 2003. With support from the James S. Kemper Foundation, CIC invited corporate leaders andcollege and university presidents to a “Symposium on the Liberal Arts and Business.” The two-daymeeting at Elmhurst College in Illinois involved intense discussions on the relationships of liberaleducation to business and how colleges and universities might view their role in responding to achanging economy.CIC believed that the next step in addressing these issues was to look at specific programs thatcombine a sound liberal arts education with preparation for careers in business. In the fall of 2006,again with the generous support of the Kemper Foundation, CIC’s membership was solicited forproposals for a symposium on “Business and the Liberal Arts: Integrating Professional and LiberalEducation.” Two-dozen institutions were selected to participate in the symposium, which was heldin Chicago, May 3–5, 2007.This report describes the programs of the schools participating in the symposium (through panelpresentations and poster sessions) and speeches by invited guests. As can be seen from the table ofcontents, a number of colleges provided imaginative ways of “blending” liberal arts material (“GreatBooks”) or concerns (attention to writing skills) into their business programs. Others achievedintegration through programs and practices that went beyond the business major including, in onecase, abolishing the major altogether. Several programs have developed successful ways of reachingout on and off the campus (service learning, “contracting”) or some specific thematic focus (ethics,innovation) as a means of improving preprofessional education in business and achieving the goalsof the liberal arts.the council of independent colleges

This typology is far less important than the overarching theme in all the presentations ofintegration. There is no single “right way” or “best practice” in integrating business and theliberal arts. Moreover, most, if not all, of the programs described in this report are doing variouscombinations of “blending” with outreach or themes or even alternatives to or within the businessmajor. Indeed, one could imagine grouping these programs in entirely different ways or subdividingthese or other categories—for example, the different pedagogical strategies (simulations, casestudies, or actual consulting) or particular uses of external resources (internships, mentor programs).Perhaps the best way to sample this variety is to use the link that each school has provided to findthe particular form or combination its program takes.Thus, any scheme describing these programs is less important than the fact that each reflectsa self-conscious effort at integrating business and the liberal arts. These efforts are constantlyevolving. As indicated in the final section of this book, symposium participants also heard aboutseveral programs “in the making” that were developing their own approaches to integration.Even the most casual perusal of this report shows that the discussions were wide-ranging,reflecting a variety of programmatic responses to integrating business and the liberal arts. Perhapsmost important, there was a high degree of agreement and optimism among the participants thatintegration can and should be achieved. The three speeches by Ryan LaHurd, Rick Stephens,and Anne Colby provide variations on this theme. Their remarks highlight the importance ofexperiential learning in both the liberal arts and business and the desirability of combining the two.Although all participants noted the institutional inertia and “silos” that create tensions in bringingbusiness faculty and programs together with their liberal arts counterparts, the range and success ofthe programs on display at the symposium demonstrated that integration can be achieved in a widevariety of ways. Indeed, the major accrediting organizations for business schools and programs—The Association of Collegiate Business Schools and Programs and the Association to AdvanceCollegiate Schools of Business—are strongly supportive of the liberal arts as part of professionalpreparation.CIC hopes that this volume will provide all smaller colleges and universities with ideas forintegrating preprofessional and liberal education. Our hope is to encourage ongoing conversationon campuses about these issues.David C. ParisSenior AdvisorCouncil of Independent Colleges Report of 2007 Symposium on the Liberal Arts and Business

opening remarksOn the first day of the symposium, the participants were greeted by Ryan LaHurd, president of the James S.Kemper Foundation, which provided funding for the symposium. LaHurd is a former professor of English,dean, and president of Lenoir Rhyne College and of the Near East Foundation. He discussed the KemperScholars Program, illustrating why integrating business and the liberal arts is so important, particularly withrespect to “the value of experiential learning.”More than 60 years ago, James Scott Kemper,founder of the Kemper Insurance Companies—at one time one of the nation’s largest and most diverseinsurance companies—set up and funded the JamesS. Kemper Foundation. The main mission of theorganization became to support the Kemper ScholarsProgram, an operational effort that responded toone of Mr. Kemper’s most strongly held beliefs: thatliberally-educated persons are the best candidatesfor organizational leadership. In a comment thatwould warm the heart of many a liberal arts collegedean or president, Mr. Kemper stated that he didnot want to hire people who had all the answers, butpreferred those who knew which questions to ask andpossessed the intellectual ability and the skill to seekthe answers. The Kemper Scholars Program each yearsupports 58 students on 15 college campuses throughsignificant scholarship assistance, mentorship, and paidsummer internships.Today the Foundation, with the same commitment,continues the Kemper Scholars Program alongwith a grants program whose goal is to supportefforts of smaller liberal arts colleges to advance theFoundation’s mission of encouraging and helpingstudents with education in the liberal arts and sciencesto make the transition to positions of leadership inAmerican for-profit and nonprofit organizations. Itis because of our shared mission that the KemperFoundation has supported the work of CIC in this areaand particularly this symposium.For most of my career I was a part of small liberalarts colleges: as a professor of English, an academicdean, and a president. I have spent much timeand devised various ways to argue the value andimportance of an education in the liberal arts andsciences. Despite pressure to accept a contrary view, Ihave always held and continue to hold that the liberalarts’ true value lies within them even though they mayadditionally have many applications to other things.I also know from these experiences that an oftencontentious conflict exists on many liberal arts collegecampuses between the so-called pure liberal arts andstudies in the professions, including and perhapsespecially business.Assuming that at least some of you have hadsimilar experiences to mine, I would like to use myfew minutes to talk about some of the things wehave learned from the James S. Kemper Foundation’slong experience with the Kemper Scholars Programthat might prove helpful to you as you consider therelationships between professional and liberal artseducation during this conference. While there aremany things I could tell you, because I do not havemuch time, I will briefly list five of the things andelaborate on one other. From our experience withKemper Scholars we have learned: First, like anyone else, students need to understanda profession before they can imagine doing itthemselves. Few students have any experience ofwhat it means to be a leader in an organization.When they experience the role through directobservation, they can see it as a possibility for theirown future. Experiential professional internshipsthus broaden their choices and possibilities.the council of independent colleges

Second, on the basis of many things, probably, butcertainly in part what they have experienced oncampus, many students from liberal arts collegesare prejudiced against business and business people.They often have the attitude that if one is going todo something to benefit humanity he or she couldnot work in business where everyone is greedy andpurely self-interested. To me it is disappointingthat such a bias is allowed to exist on campuseswhich would never allow students to express biasesbased on sex, race, sexual orientation, or disability.This is the United States. No one will be a trulyeffective and contributing citizen here with thisfalse prejudice. Third, even students with very high gradepoint averages and with genuine success in theacademic environment express great excitementand satisfaction and an enhanced sense of selfconfidence and motivation when they are toldby their internship supervisors that they haveaccomplished a task with professionalism.Experiential internships can give students renewedenergy for and satisfaction with their education. Fourth, most CEOs of organizations express anappreciation of and preference for employees withbroad liberal arts backgrounds because they arecurious and analytical, good at communicatingand solving problems, adaptable, and ethicallyaware. At the same time, it is clear that these CEOs(unlike James S. Kemper) most often apparently donot transmit these values to those in their humanresource departments who hire recent collegegraduates and who value specific technical skillsover broad educational background. This is an areaof discrepancy it would do all of us well to work atrevealing and changing. Fifth, demanding that students be reflective abouthow their experience in internship placementsrelates to and draws upon their college academicwork, about what they are learning aboutthemselves and others, and about what theyhave yet to learn turns out to be a most valuablepedagogical and developmental technique.Students learn to apply, analyze, and synthesizeusing their experience as the subject. They makeastute observations about their college work.But beyond these things and many other specificobservations I could make about what we have learnedfrom the Kemper Scholars Program’s insistenceon experiential education in the professionalenvironment, I consider one other to be mostvaluable to your considerations in this symposium.In fact, colleges have already demonstrated the valueof experiential education on campus in majors likebiology, chemistry, physics, theatre, and music. Noone thinks students have completed a major in thesefields unless they have been in the laboratory, on stage,or in the practice room or studio having done thethings which professionals working in those fields inthe nonacademic world actually do. In many majorsof the humanities and social sciences, however, rarelydo students experience what professionals otherthan academic professionals do. Their experience isoften limited to writing papers and making scholarlyarguments akin to those in academic journals. It isdifficult or impossible for these students to see theconnection between their education and some futurecareer unless they plan to be a professor.What I have seen is this: experiential education ina professional environment is not a threat to the liberalarts but a strong argument for their value. Experientialeducation does not become a demonstration of aliberal arts education’s incompleteness or its ivorytower uselessness. In fact, I have observed that effortsto argue abstract correspondences of usefulnessbetween liberal arts courses or majors and professionalskills are demeaning to both the liberal arts and theprofessions. I mean, for example, something like tellingstudents: “English majors are educated to be goodwriters and many jobs require communication skills.An English major could help you get a job.” What Ihave discovered—a revelation to me though perhapsnot to others—is that experiential education in theprofessional environment turns out to be a testing,shaping, and proving not of the liberal arts educationbut of the liberally-educated person.10 Report of 2007 Symposium on the Liberal Arts and Business

In the professional workplace with challengingwork and a helpful mentor, students experience whatthey can do and cannot do (usually much more of theformer), and what they know and do not know. Intheir reflections they come to see how much they havelearned in school and, in a Socratic revelation, howmuch they yet need to learn. They are often surprisedby the skills they actually need and use as opposed tothose they had imagined they would need and use.Perhaps the best illustration I can think of occurredlast September at our Kemper Scholars Conferenceduring which scholars make public presentations ontheir reflections about what they learned in theirinternships the previous summer. One of our KemperScholars from Xavier University in New Orleans,a communications major who worked at a Chicagopublic television station, told his fellow scholars thatbefore the experience he had thought he would mostuse what he had learned in his communication courses.In fact, he said, the course he used most turned out tobe one in theology because it had taught him to be acritical thinker, and he had been called upon to solvemany complex situations in his job.As his comment illustrates, our Kemper Scholarscome to know experientially that their liberal artseducation is valuable because they themselves—theproducts of such an education—are valuable to theirsupervisors and organizations; and they can articulateexactly how their education has developed them so far.They experience the gaps in their education and makeplans to fill the gaps when they get back to campus.They apply their education well beyond the tasks ofthe job into such areas as analyzing organizationalmission, ethical behavior, and human interactionsin the workplace. Based on this experience, I wouldargue that the most valuable integration betweenprofessional and liberal education will happen inexperience rather than in the classroom.I once overheard a college professor answering thequestion of parents of a prospective student aboutwhether their son who wanted to be a history majorwould learn anything that would help him in a careerafter college. “Well,” said the professor with a grin,“he will have a lot to talk about at cocktail parties.”I am here to tell you that the students I have workedwith as Kemper Scholars would offer a much moreastute answer.“I have observed that efforts to argue abstract correspondences of usefulnessbetween liberal arts courses or majors and professional skills are demeaning toboth the liberal arts and the professions . . . for example, telling students: “Englishmajors are educated to be good writers and many jobs require communication skills.An English major could help you get a job.” What I have discovered—a revelation tome though perhaps not to others—is that experiential education in the professionalenvironment turns out to be a testing, shaping, and proving not of the liberal artseducation but of the liberally-educated person.”—Ryan LaHurdthe council of independent colleges 11

Program Profiles:“Blending” the Liberal Arts into Business ProgramsIn her remarks before the closing session of the symposium Anne Colby, Senior Scholar at the CarnegieFoundation for the Advancement of Teaching, noted that there are several ways of achieving integrationbetween preprofessional education in business and the liberal arts. One straightforward way she called“blending” introduces elements of the traditional liberal arts into a business program or major. Almost all ofthe 24 programs that were presented at the symposium engaged in some “blending.” The programs belowprovide particularly promising ways of doing so.Birmingham-Southern College:The Great Writers and BusinessStephen Craft, Dean of Business Programs and EltonB. Stephens Professor of Marketingwww.bsc.edu/academics/business/index.htmA liberal arts education typically involves someencounter with classic works of philosophy andliterature. Whether through a prescribed “GreatBooks” curriculum or some form of distributionrequirements, a liberal arts curriculum includes the“best that has been thought and written.”The “introduction to business” course is a commonfeature of academic business programs in manyinstitutions. At Birmingham-Southern College,Foundations of Business Thought, a prerequisite for allupper-level courses in business, has been transformedto link students’ forthcoming professional preparationin business with traditional education in the liberalarts by examining the views of classic authors onbusiness topics.For each area of thebusiness curriculum,the Foundations ofBusiness Thoughtcourse links traditionalbusiness topics to writersfrom across eras andgenres of philosophyand social thought.For example, studentsare offered a traditional introduction to investmentsand credit markets while reading Saint ThomasAquinas on the practice of usury. Similarly, studentsexamine international trade and culture while readingChristopher Columbus, technology in light of readingsfrom Gandhi and Mark Twain, and business ethicsthrough the writings of Plato and Aristotle.The goal of the introductory course, Professor Craftnoted, is to create the “habit of integration” in puttingbusiness endeavors in the “context of a person’s life.”Through these readings students are asked to addressfundamental questions regarding the role of businessentities in the culture, the value of consumption asan end unto itself, the role of entrepreneurship as ameans to building community assets, the appropriaterole for public policy in a “winner-take-all” economicsystem, and how to reconcile a career in business withan ethical and socially aware life. Not surprisingly, thecourse attracts many nonmajors as well.“The goal of the business program at BirminghamSouthern is to create people better qualified to makehuman decisions in leadership positions in business.”—Stephen Craft12 Report of 2007 Symposium on the Liberal Arts and Business

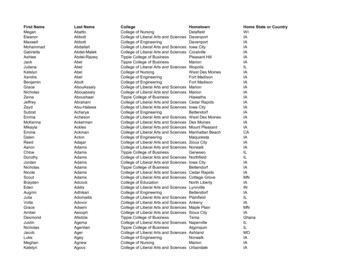

Syllabus for the Foundations of Business Thought class atBirmingham-Southern CollegeTUESTHUR2/06Syllabus2/082/13Introductions andDiscuss Class FormatDefining Business—US Business Environment2/152/20Bacon, Thoreau, DuBoisConducting Business Ethically andResponsibly (Paper I Assigned)2/222/27Business Fundamentals: Plato, AristotleUnderstanding Entrepreneurship andBusiness Ownership3/013/06Business Fundamentals:Rand, Confucius, SmithUnderstanding the Global Context ofBusiness (Paper I Due)3/083/13Business Development: ColumbusExam I3/153/20Exam ResultsSPRING BREAK3/223/27SPRING BREAKManaging & Organizing the BusinessEnterprise3/294/03Business Fundamentals:Rockefeller & ThoreauManaging Human Resources/ Motivating& Leading Employees4/054/10To Be AnnouncedUnderstanding Marketing Processes andConsumer Behavior Pricing, Distributingand Promoting Products4/124/174/194/244/26Daniel Condon, Professor of Economicshttp://domin.dom.edu/depts/RCAS/LAS seminars/index.htmDominican University provides a model of “blending”liberal arts and business through common coursesthat is similar to Birmingham-Southern College. Allstudents at Dominican University, including businessmajors, are required to enroll, according to their classstanding, in a Liberal Arts and Sciences (LA&S)seminar. There is a specific theme for each class level: Freshman Seminar: Dimensions of the Self Sophomore Seminar: Diversity, Culture,and Community Junior Seminar: Technology, Work, and Leisure Senior Seminar: Virtues and ValuesPrinciples of AccountingEach of these themes in turn has specific questionsaround which the seminar is organized. For example,the questions for the junior seminar include: Whatis wo

The Council of Independent Colleges is an association of more than 570 independent liberal arts colleges and . Business Faculty Teaching in 29 Liberal Arts Programs . Learning Scott Ambrose, Chair and Assistant Professor of Business progrAm profIles: 31 Using a Thematic Focus to Integrate Business and the Liberal Arts Christian Brothers .