Transcription

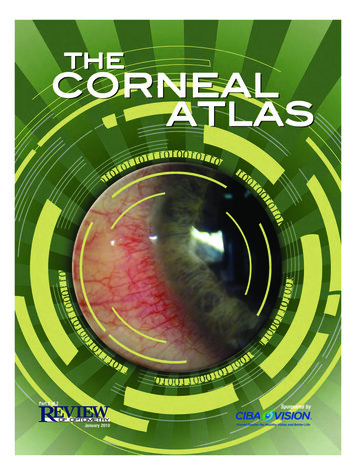

Part 2 of 2Sponsored byJanuary 2010001 ro0110 Corneal Atlas ac2.indd 11/7/10 5:33 PM

Ernest Bowling, OD, FAAO, is Center Directorfor VisionAmerica, a surgical co-managementcenter in Gadsden, AL, and associate clinicaleditor of Review of Cornea & Contact Lenses.E-mail him at drbowling@windstream.net.Table of ContentsBacterial . 4Viral . 5Acanthamoeba Keratitis . 6Gregg Eric Russell, OD, FAAO, is in privatepractice at the Marietta Eye Clinic in Atlanta.His clinical interests include dry eye, contactlenses and refractive surgery. E-mail him atgrussell@mariettaeye.com.Fungal . 8Epithelial . 9Bowman’s . 11Stroma . 11Joseph P. Shovlin, OD, FAAO, is in privatepractice in Scranton, PA, associate clinical editor of Review of Optometry and clinical editorof Review of Cornea and Contact Lenses.E-mail him at jpshovlin@gmail.com.Endothelium . 15Degenerations . 16Mechanical . 17Christine W. Sindt, OD, FAAO, is Director ofContact Lens Service at the University of IowaHospitals and Clinics, Iowa City, IA, a monthlycolumnist for Review of Cornea and ContactLenses, co-clinical editor for Review ofOptometry, and photo editor for the CornealAtlas. E-mail her at christine-sindt@uiowa.edu.49Chemical . 19Inflammatory . 21151822REVIEW OF OPTOMETRY001 ro0110 Corneal Atlas.indd 3January 201031/7/10 5:46 PM

BacterialMICROBIAL KERATITISEtiologyMicrobial keratitis is the most common,sight-threatening condition related to contactlens wear. While even daily wear of contactlenses carries an increased risk for infection,extended or overnight contact lens wear isthe greatest risk factor for infectious keratitisin patients choosing to wear contact lenses.Many bacteria have been identified in contactlens related microbial keratitis, with the mostcommon organisms cultured from bacterial ulcers being Staphylococcus, Streptococcus,Pseudomonas and Moraxella. The gram-negative rod Pseudomonas aeruginosa is commonlyassociated with soft contact lens wear. It isimportant to remember that the organismsNeisseria gonorrhoeae, Listeria, Corynebacteriumand Haemophilus aegypticus do not requiredamage to the cornea and may invade directly through intact corneal epithelium.PresentationPatients with microbial keratitis presentwith symptoms including decreased vision,photophobia, moderate to severe ocular pain,redness, swelling and discharge. On slit lampexamination, the critical finding is a focalwhite opacity in the corneal stroma with anoverlying corneal epithelial defect that stainswith fluorescein. Additional findings includediffuse epithelial edema, stromal infiltrationsurrounding the ulceration, and mucopurulent exudation. An anterior chamber reactionmay be present, and there may be a hypopyon. It is important to document the depthand location of the epithelial defect and stromal infiltration. The anterior chamber shouldbe evaluated for cells and flare and examinedfor a hypopyon, and the intraocular pressureshould be checked.Serratia marcescensPseudomonas corneal ulcerMuch has been made regarding cultureand sensitivity testing in cases of microbialkeratitis. In general, consider cultures inulcers greater than 1 mm to 2 mm, defects inthe visual axis, ulcers unresponsive to initialtherapy, or if an unusual organism is suspected. Remember that only approximately40% of corneal cultures indentify causativepathogens.Infectious keratitis may worsen with topicalsteroid use, especially when caused by fungus, atypical mycobacteria or pseudomonas.Once the cornea has re-epithelialized and thecausative organism has demonstrated sensitivity to the antibiotic (usually after 72 hoursof treatment), a steroid may be added to thetherapeutic regimen to control persistentinflammation and reduce tissue damage.The patient with an infectious keratitisneeds to be followed daily, with carefulmonitoring of the findings. The antibioticregimen should be reduced depending on theresponse, but should never be tapered belowthe minimum dose (usually q.i.d. to t.i.d.) toprevent the possibility of bacterial resistance.TreatmentUlcers need to be considered infectiousuntil proven otherwise. Therapy begins withimmediate, intensive, aggressive treatmentwith fourth-generation fluoroquinoloneswhile awaiting lab results. Dosage is every 30minutes for the first six hours, followed byhourly administration around the clock untilimprovement is noted. The use of fourthgeneration fluoroquinolones in the treatmentof corneal ulcers is an off-label use of thesemedications, but routinely used. In severeulcers, consider using fortified antibiotics.Cycloplegic drops are valuable for patientcomfort and to prevent synechiae formationin accompanying iritis.AVOID STEROIDS! Especially initially.ICD-9 Codes 370.00 Corneal ulcer, unspecified 370.01 Marginal corneal ulcer 370.02 Ring corneal ulcer 370.03 Central corneal ulcer 370.04 Hypopyon ulcer 370.05 Mycotic corneal ulcer 370.06 Perforated corneal ulcer 371.00 Corneal opacity/scar,aunspecified (upon resolution)ReferencesStaphlococcus AureusMycobacteriumLevy B. Infectious keratitis: What have we learned? Eye ContLens 2007; 33 (6): 418-420.Reed WP, Williams RC. Bacterial adherence: First step inpathogenesis of certain infections. J Chronic Dis 1978; 31:67.Ehlers JP, Shah CP, eds. The Wills Eye Manual: Office andEmergency Room Diagnosis and Treatment of Eye Disease,5th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2008:62-66.Koidou-Tsiligianni A, Alfonso E, Forster RK. Ulcerative keratitis associated with contact lens wear. Am J Ophthalmol1989;108: 64-67.Keay L, Stapleton F, Schein O. Epidemiology of contact-lensrelated inflammation and microbial keratitis: A 20-year perspective. Eye Cont Lens 2007; 33 (6): 346-353.mon. Adenoviruses produce the mostcommon viral conjunctival infections.The most common serotypes involved are3, 8, 19 and 37. The condition is quitecontagious and is transmitted readily inrespiratory and ocular secretions, eyeViral InfectionsADENOVIRAL KERATOCONJUNCTIVITISEtiologyViral conjunctivitis is extremely com4 January 2010 REVIEW OF OPTOMETRY001 ro0110 Corneal Atlas ac2.indd 41/7/10 5:34 PM

droppers, mascara bottles and contaminated swimming pools. The incubationperiod is usually five–12 days, and theclinical illness is present for five–15 days.Most cases of viral conjunctivitis resolvespontaneously, without sequelae, withindays to weeks.There are four forms of adenoviralconjunctivitis: Follicular conjunctivitis,pharyngoconjunctival fever, epidemic keratoconjunctivitis (EKC) and acute hemorrhagic conjunctivitis. Follicular conjunctivitis is the mildest form of adenoviralconjunctivitis. Pharyngoconjunctival feveris the most common ocular adenoviralinfection and is characterized by a combination of pharyngitis, fever and conjunctivitis. Epidemic keratoconjunctivitis (EKC)is a more severe form of conjunctivitis,and typically lasts for seven–21 days. EKCcan affect the cornea with coarse keratitisand sub-epithelial infiltrates (SEIs). SEIsmay last for months, affecting visual acuity. Acute hemorrhagic conjunctivitisproduces a severe, painful follicular conjunctivitis with the development of tinysubconjunctival hemorrhages.PresentationIn general, viral infections presentwith redness, irritation, itching, foreignbody sensation, tearing and photophobia.The condition starts in one eye and thenprogresses to the other a few days later.Signs include conjunctival injection andswelling. The lids may be swollen. Inferiorpalpebral conjunctival follicles are seen.Pinpoint subconjunctival hemorrhagesand membrane formation over the palpebralconjunctiva are occasionally seen. In somecases, multiple, focal infiltrates in the corneaanterior to mid-stroma may be seen. A preauricular lymphadenopathy is present. TheRPS Adeno Detector has high sensitivity andspecificity and can provide a quick, in officedifferential diagnosis of viral infection.TreatmentPalliative therapy is often sufficient formost cases of adenoviral conjunctivitis:HSV dendritecold compresses, artificial tears and topical decongestants/antihistamines. Topicalsteroids are indicated when the visual axisis involved or membrane or pseudo-membrane formation is noted. Patients shoulddiscontinue contact lens wear. Avoidthe use of topical and oral antibiotic orantiviral agents as these will not help resolution and may promote antibiotic resistance. Educate the patient as to the highlycontagious nature of the disease, whichmay require weeks for total resolution.ICD-9 Codes 372.00 Unspecified conjunctivitis 372.02 Acute follicular conjunctivitis 372.03 Other mucopurulent conjunctivitis 372.04 Pseudomembranous conjunctivitis 372.11 Simple chronic conjunctivitis 077.10 Epidemic keratoconjunctivitis 077.30 Adenoviral (acute follicular)Herpes Simplex KeratitisEtiologyThe herpes simplex virus (HSV) is theleading cause of vision loss in the UnitedStates. Keratitis caused by HSV is themost common cause of cornea-derivedblindness in developed nations. The HSVis a DNA virus that resides latent in thetrigeminal ganglion, only to resurrect during periods of intense stress, illness, irritation and phototoxic exposure. The diseasecan be present as superficial lesions, neu-Geographic HSV ulcerHSC keratitis stained w/ LGrotrophic disease, or with deep stromalinvolvement.PresentationPatients with HSV infection present with rapid onset unilateral pain andredness, watering and light sensitivity.Diagnosis of HSV infection is primarilybased on clinical findings. The diseasestarts as a punctuate epithelial keratitis,coalescing into the classic branching epithelial ulceration with terminal end bulbswithin 24 to 48 hours. The dendritesstain with rose bengal or lissamine green.Corneal sensitivity may be decreased.The neurotrophic form of HSV disease ischaracterized by areas of intense punctatechange or epithelial denudement, and canresult in corneal scarring. Deep stromallesions appear as a round, fluid filledcircle. Scarring can develop in later stageswith loss of stromal thickness and cornealthinning.TreatmentHSV dendriteStromal herpesTreatment of active HSV keratitisconsists of topical trifluridine 1% solution every one to two hours until nosign of active infection (lack of dendritepatterns), then five times a day for anadditional seven to 10 days. Topicalacyclovir 3% ointment (no longer commercially available, but can be obtainedfrom specialized compounding pharmacies) used five times a day is an alternativein patients with a known sensitivity totrifluridine.Oral antivirals are gaining use in theREVIEW OF OPTOMETRY001 ro0110 Corneal Atlas ac2.indd 5January 201051/7/10 5:34 PM

matous or granulomatous anterior uveitiswith keratic precipitates and posterior synechiae. The diagnosis of herpes zoster disease is generally based on clinical findings.treatment of epithelial disease. Oral acyclovir 400mg five times a day is the mostcommon oral dosage. For a patient onlong-term oral antiviral therapy for recurrent disease, check creatinine levels toinsure there is no liver damage.TreatmentICD-9 Codes 054.43 Herpes keratitisHERPES ZOSTEREtiologyHerpes zoster ophthalmicus (HZO) isa recurrent infection of varicella (chickenpox) in the ophthalmic division of thetrigeminal dermatome, most often affecting the nasociliary branch. HZO canaffect any of the ocular and adnexal tissues. HZ has the highest incidence of anyneurologic disease, and develops morefrequently in the elderly.Bulbar conjunctival follicles in EKCPresentationHZO usually begins as an influenza-likeillness characterized by fatigue, malaise,nausea, and mild fever accompanied byprogressive pain and skin hyperesthesia.A diffuse erythematous or maculopapularrash appears over a single dermatomethree–five days later. The skin of theforehead and upper eyelid is commonlyaffected and strictly obeys the midlinewith involvement of one or more branchesof the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve. HZO conjunctivitis is a common ocular finding, and the conjunctivaappears swollen and injected, with occasional vesicles and petechial hemorrhages.Herpes zoster keratitis manifests in fivebasic clinical forms: Epithelial keratitis (acute or chronic).Multiple, fine, raised intraepitheliallesions located paracentrally or at the limbus, which stain mildly with fluorescein,but intensely with rose bengal. Nummular stromal keratitis.Palpebral conjunctival follicles in EKCMultiple, fine, granular infiltrates in theanterior corneal stroma. Disciform keratitis. A central, welldefined, disc-shaped area of diffusestromal edema without vascularization.Corneal edema with anterior chamberinflammation. Limbal vascular keratitis. Limbalvessel ingrowth and stromal edema. Maybe associated with adjacent episcleral orscleral inflammation. Neurotrophic keratitis. An inferior,oval epithelial defect with rolled edges.Can lead to corneal perforation.HZO can cause either a nongranulo-Patients with HZO are treated withoral acyclovir (800mg, five times daily)for seven–10 days. Acyclovir can shortenthe duration of pain if taken within thefirst three days of onset of symptoms.Famciclovir 500mg three times dailyfor seven days or Valacyclovir 1000mgthree times daily are alternatives to acyclovir. Palliative therapy, including coolcompresses, mechanical cleansing of theinvolved skin, and topical antibiotic ointment without steroid, is helpful in treatingskin lesions. Epithelial defects associatedwith HZ keratitis may be treated with nonpreserved artificial tears, eye ointments,punctal occlusion, pressure patching, ortherapeutic soft contact lenses. Topicalsteroids are useful in the management ofkeratouveitis, interstitial keratitis, anteriorstromal infiltrates and disciform keratitis.Topical cycloplegics prevent ciliary spasmassociated with herpes zoster inflammatorydisease. Aqueous suppressants and topicalcorticosteroids should be used to treat glaucoma associated with HZ disease.ReferencesYanoff M, Duker JS, eds. Ophthalmology, 3rd ed.Maryland Heights, MO, Elsevier, 2009.Guess S, Stone DU, Chodosh J. Evidence-based treatment of herpes simplex virus keratitis: a systematicreview. Ocul Surf 2007; 5(3): 240-50.Kahn BF, Pavan-Langston D. Clinical manifestations andtreatment modalities in herpes simplex virus of the ocularanterior segment. Int Ophthalmol Clin 2004; 44: 103-133.Gordon, JS; Aoki, K; Kinchington, PR. Adenovirus keratoconjunctivitis. In: Pepose JS, Holland GN, Wilhelmus KR,eds. Ocular Infection and Immunity. St. Louis: Mosby;1996. pp. 877–894.Ehlers JP, Shah CP, eds. The Wills Eye Manual: Officeand Emergency Room Diagnosis and Treatment of EyeDisease, 5th Ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Willliamsand Wilkins, 2008.Acanthamoeba KeratitisBackground:Acanthamoeba keratitis can be severe andvision-threatening. It was first recognized incontact lens wearers in the early 1970s, andcontact lens wear is thought to be associatedwith 80% of the cases. Acanthamoeba speciesare found in virtually every environment.These protozoa are ubiquitous in the soil,dust, lakes, rivers, hot tubs and salt water.They have been isolated from heating,venting and air conditioner units (HVAC),humidifiers, dialysis units and contact lensparaphernalia. Acanthamoeba have been foundin the nose and throat of healthy people aswell as those with compromised immunesystems. Contact lens wear and poor lenshygiene are often singled out as the biggestrisk factors for Acanthamoeba keratitis. Thetrue incidence is not known; however, it isthought to be rare; affecting approximately1.65-2.01 per million contact lens wearers peryear in the United States. Although, it hasbeen reported as high as 1/30000 contact lenswearers per year outside the United States.Etiology:There are more than 20 different species,several of which are known to cause infections in humans, including A. culbertsoni,A. polyphaga, A. castellanii, A. healyi, (A.astronyxis), A. hatchetti and A. rhysodes. A. castellanii is the most common amoeba associated with corneal infection. The life cycle ofthese organisms is comprised of two stages,trophozoite and cystic forms. Trophozoitesbind to and desquamate the corneal epithelium. They secrete a variety of proteases,which facilitate the dissolution of the cornealstroma. When environmental conditionsbecome unfavorable, the organism convertsto a dormant cystic form, which is able tosurvive many years. These double walledcysts are highly resistant to killing by desiccation, freeze/thaw cycles, irradiation, chlorination levels and antimicrobial agents.6 January 2010 REVIEW OF OPTOMETRY001 ro0110 Corneal Atlas ac2.indd 61/7/10 5:34 PM

Co-infection with bacteria or fungi iscommon, providing food for amoeba.Presentation:Acanthamoeba keratitis presents withpain (ranging from mild foreign bodysensation to severe pain), photophobia,decreased vision, injection, irritation,tearing and a protracted clinical course.The patient often presents with a unilateral red eye, where the pain is disproportionately worse than one would surmisefrom the clinical appearance. Early corneal findings include irregular epithelium,punctuate epithelial erosions, microcysticedema, perilimbal injection and dendritiform epithelial lesions. The dendritiformlesions often resemble those of herpessimplex keratitis, however, the AK lesionsappear edematous and necrotic ratherthan frank ulcerations.A ring infiltrate is classically thoughtof as the defining sign of Acanthamoebakerititis; however, it tends to form foureight weeks after onset of symptoms and israrely the presenting sign. Radial perineuritis (perhaps explaining the intense pain)may be seen on slit lamp examination orconfocal microscopy. Unchecked, theremay be progressive corneal thinning andrisk of perforation. Up to 40% of patientsmay have mild to severe anterior uveitis.Scleritis has been reported in patientswith Acanthamoeba keratitis; however, thescleral inflammation was attributed to animmune-mediated response to necroticorganisms and was not believed to be theresult of active infection.Severe glaucoma has been associatedwith Acanthamoeba keratitis secondary toan inflammatory angle-closure mechanism,apparently without direct infiltration ofthe organism.Treatment:Diagnosis largely depends on the ability to visualize the organism. Definitivediagnosis is made by corneal scrapings.Confocal microscopy is clinically useful to quickly identify the organism invivo. Attempts to culture the organismis time-consuming and expensive, oftenwith poor yields. Differential diagnosisincludes herpetic keratitis, bacterial keratitis, toxic keratopathy (solution related),stem cell failure, fungal keratitis, severedry eye and contact lens-related cornealoxygen deficiency.Debridement, particularly early inthe disease, will reduce the number oforganisms and deprive the Acanthamoebaof its food supply. Cationic antisepticagents, such as chlohexidine 0.02% andpolyhexamethyl biguanide 0.02%, aregenerally considered primary medicaltreatments. Biguanides disrupt the phos-pholipid structure of cell membranes.Aromatic diamides (Brolene) directlyaffect the amoebas nucleic acids andare thought to have a synergistic affectwith the biguanides. There is a risk ofsignificant corneal epithelial toxicity withq1-2h dosing.Corticosteroids are used totreat associated uvetitis or scleritis; however, this should be done with extremecaution because trophozoite proliferation has been observed when exposed tosteroids. Penetrating keratoplasty (PKP)may be necessary for tectonic or opticalcorneal rehabilitation. In most situations,PKP is postponed until resolution ofinfection. There may be residual dormantcysts in the peripheral corneal, even ina cornea that appears quiet, which mayincite infection after graft. After cornealtransplant, protective, maintenancedoses of medication should be usedto help prevent the recurrence of theAcanthamoeba infection.Recommendations:Avoid swimming with contact lenses on.Showering in contact lenses may increaserisk of infection.Careful following of recommended lenscare systems.ICD-9 Codes 370.02 Ring corneal ulcer 370.40-006.8 KeratoconjunctivitisReferences:Jones DB, Visvesvara GS, Robinson NM. Acanthamoebapolyphaga keratitis and Acenthamoeba uveitis associated withfatal meningoencephalitis. Transactions of the ophthalmological societies of the United Kingdom 1975, 95(2):221-232.Illingworth CD, Cook SD, Karabatsas CH, Easty DL.Acanthamoeba keratitis: risk factors and outcome. Br JOphthalmol. 1995 Dec;79(12):1078-82.Schaumberg DA, Snow KK, Dana MR. The epidemic ofAcanthamoeba keratitis: where do we stand? Cornea. 1998Jan;17(1):3-10. Review.Seal DV. Acanthamoeba keratitis update-incidence, molecular epidemiology and new drugs for treatment. Eye. 2003Nov;17(8):893-905. Review.Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science, July 2005,Vol. 46, No. 7.Lee GA, Gray TB, Dart JK, et al. Acanthamoeba sclerokeratitis: treatment with systemic immunosuppression.Ophthalmology. 2002;109:1178-1182.Garner A. Pathogenesis of Acanthamoebic keratitis:hypothesis based on a histological analysis of 30 cases. BrJ Ophthalmol. 1993;77:366-370.Lindquist TD, Fritsche TR, Grutzmacher RD. Scleralectasia secondary to Acanthamoeba keratitis. Cornea.1990;9:74-76.Kelley PS, Dossey AP, Patel D, Whitson JT, Hogan RN,Cavanagh HD. Secondary glaucoma associated withadvanced Acanthamoeba keratitis. Eye Contact Lens. 2006Jul;32(4):178-82.Lindquist TD. Treatment of Acanthamoeba keratitis. Cornea.1998 Jan;17(1):11-6.Seal D. Treatment of Acanthamoeba keratitis. Expert RevAnti Infect Ther. 2003 Aug;1(2):205-8. Review.Hammersmith KM. Diagnosis and management ofAcanthamoeba keratitis. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2006Aug;17(4):327-31.McClellan K, Howard K, Niederkorn JY, Alizadeh H. Effectof steroids on Acanthamoeba cysts and trophozoites.Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001 Nov;42(12):2885-93.Acanthamoeba cysts on confocal.MicrosporidiumVisvesvara GS, Stehr-Green JK. Epidemiology of freeliving ameba infections. The Journal of protozoology 1990,37(4):25S-33S.Joslin, CE, Tu, EY, Stayner L, Davis F. The associationbetween Acanthamoeba keratitis and showering with contact lenses. Paper presented at the American Academy ofOptometry October 22, 2008REVIEW OF OPTOMETRY001 ro0110 Corneal Atlas ac2.indd 7January 201071/7/10 5:34 PM

Fungal KeratitisFungal keratitis is relatively rare in theUnited States (approximately 5% to 10% ofreported cases), although it accounts for upto 50% of ulcerative keratitis elsewhere inthe world. Fungal keratitis is usually associated with a history of ocular trauma, ocularsurface disease, or topical steroid use. Therehas been a lot of attention focused on therecent epidemic of fungal keratitis in softcontact lens wearers in 2005 and 2006, however, a recent review indicates the number offungal keratitis cases associated with contactlens wear has been steadily increasing thepast 20 years.EtiologyFungi require an epithelial defect for corneal penetration. Once the epithelium hasbeen violated, the present fungi can multiplyand cause severe tissue damage. Up to 30% offungal keratitis cases may be associated withbacterial co-infection. Risk factors for thedevelopment of fungal keratitis include ocular trauma, topical corticosteroids, systemicimmunosuppression, penetrating or refractive surgery, chronic keratitis (vernal/atopickeratitis and neurotrophic ulcers) and contactlens wear.PresentationPatients present with pain, photophobia,injection, tearing and possible discharge;however, the degree of symptoms may vary.In some cases, the progression of symptomsmay be slow, while in others it may movevery quickly. Corneal infiltrates tend to havefeathery borders, are generally grayish-white,and may have satellite lesions. Larger infiltrates are associated with poor visual prognosis. The epithelium is usually raised, and attimes may be intact, over the infiltrate. Anepithelial defect, anterior chamber reactionor hypopyon may be present.Diagnosis may be difficult based on clinical examination alone. Confocal microscopymay reveal hyphae in filamentary fungaldisease such as Aspergillus or Fusarium, orbudding yeast forms such as Candida. Fungalcultures are the gold standard for diagnosis.Corneal scrapings and cultures may be positive in up to 90% of initial scrapings. Mostfungi grow well in blood agar or Sabourauddextrose agar as culture media. Growth usually occurs within three or four days but cantake as long as four to six weeks. Gram andGiemsa stains or potassium hydroxide (KOH)wet mounts are useful for identifying fungalelements. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) isanother diagnostic tool. Results from clinicalstudies suggest that PCR is more sensitivethan culture as a diagnostic aid in ocular fungal infections and is also much faster. ResultsAcremonium infectionAlternariaare known within 24 hours. However, PCRis associated with a high false-positive rate. Ifthere is strong suspicion of fungus and othertests are negative, biopsy may be required.reduce the patient’s immune ability to eliminate infection.TreatmentTopical natamycin 5% or topicalamphotericin B 0.15% is first-line therapyfor symptoms of suspected superficialfungal keratitis. Natamycin is currently theonly topical ophthalmic antifungal compound approved by the FDA. It penetratesthe cornea well after topical administration and is the drug of choice for fungalkeratitis. Amphotericin B, because of itsnumerous toxicities, is administered asa second-line treatment to natamycin.Recommended dosage is 1 mg/kg/dayintravenously or topically in 0.15% to0.3% solution every 30 to 60 minutes.Side effects can include renal toxicity,headaches, fevers, chills and anorexia.As is the case for most anterior segmentinjuries and infections, cycloplegics shouldbe dispensed to improve patient comfort.In addition to standard therapy for fungalkeratitis, Voriconazole (topical and oral)has also been successfully used to impart aclinical cure.Mechanical debridement of the cornealepithelium may aid in penetration oftopical medication into the stroma whileproviding a specimen for histopathological stains and evaluation. Therapeuticpenetrating keratoplasty is often requiredto restore vision impairment due to corneal scarring. Despite maximum pharmacologic therapy, early transplant duringactive disease may be required early incases of perforation or near perforation.As many as 27% of patients with ocularfungal infections can require cornealtransplants.The use of topical steroids is detrimentalin the treatment of fungal keratitis. Extremecaution should be used with steroids until asufficient amount of time for clinical stabilization has been achieved because steroidsRecommendationsEarly on, the patient may present with nomore than a “gritty” foreign body sensationCandidaAlternaria – different viewFungal ulcer8 January 2010 REVIEW OF OPTOMETRY001 ro0110 Corneal Atlas ac2.indd 81/7/10 5:34 PM

Optimal contact lens care. Nearly all ofthe cases of contact-lens related fungal keratitis reported from a University of Floridastudy showed poor contact lens care.ICD-9 Codes 370.05 Mycotic corneal ulcer 370.04 Hypopyon corneal ulcerReferences:Verticillium fungal ulcerwith only a small, indistinct infiltrate.Fungal keratitis is commonly confusedwith bacterial keratitis. There should be ahigh level of suspicion of fungal agents ifthe lesions do not resolve/improve despiteantibiotic therapy.Steroids will worsen/exacerbate the diseaseand should not be used in suspected fungalinfections.Chang DC, Grant GB, O’Donnell K, et al. Multistate outbreak of Fusarium keratitis associated with use of a contactlens solution. JAMA 2006; 296(8): 953-63.Rosa RH Jr, Miller D, Alfonso EC. The changing spectrumof fungal keratitis in south Florida. Ophthalmology 1994;101: 1005-1113.Wong TY, AuEong KG, Chan WK, et al. Fusarium keratitisfollowing the use of topical anti biotic-corticosteroid therapyin traumatized eyes. Ann Acad Med Singapore 1996; 25:862-865.Khor WB, Aung T, Saw SM, et al. An outbreak of Fusariumkeratitis associated with contact lens wear in Singapore.JAMA. 2006;295(24):2867-73.Tuli SS, Iyer SA, Driebe WT. Fungal keratitis and contactlenses: an old enemy unrecognized or a new enemy on theblock? Eye Cont Lens 2007; 33 (6): 415-417.Kaufman SC, Musch DC, Belin MW, et al. Confocal microcopy: a report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology.Ophthalmology 2004; 111(2): 396-406.Klont RR, Eggink CA, Rijs AJ, et al. Successful treatmentof Fusarium keratitis with cornea transplantation and topical and systemic voriconazole. Clin Infect Dis 2005; 40(12):110-112.Hu WS, Fan VC, Koonapareddy C, et al. Contact lensrelated fusarium infection: case series experience in NewYork City and review of fungal keratitis. Eye Cont Lens2007; 33 (6): 322-328.Thomas PA. Current perspectives on ophthalmic mycoses.Clin Microbiol Rev 2003; 16: 730-797.O’Brien TP. Therapy of ocular fungal infections. OphthalmolClin North Am 1999; 12: 33-50.Winchester K, Mathers WD, Sutphin JE. Diagnosis ofAspergillus keratitis in vivo with confocal microscopy.Cornea 1997; 16(1): 27-31.O’Day DM, Ray WA, Robinson RD. Efficacy of antifungalagents in the cornea. II. Influence of corticosteroids. InvestOphthalmol Vis Sci 1984; 25: 331-335.Krachmer JH, Mannis MJ, Holland EJ. Corn

Mycobacterium spective. Eye Cont Lens 2007; 33 (6): 346-353. Serratia marcescens Staphlococcus Aureus ICD-9 Codes † 370.00 Corneal ulcer, unspecified † 370.01 Marginal corneal ulcer † 370.02 Ring corneal ulcer † 370.03 Central corneal ulcer † 370.04 Hypopyon ulcer † 370.05 Mycotic corneal ulcer † 370.06 Perforated corneal ulcer