Transcription

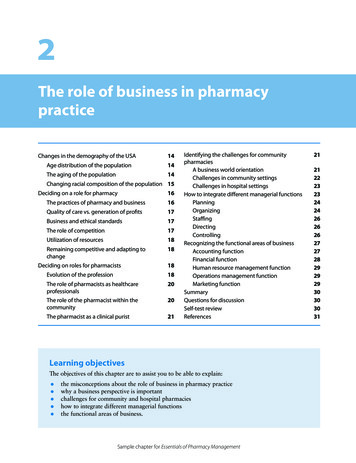

2The role of business in pharmacypracticeChanges in the demography of the USA14Age distribution of the population14The aging of the population14Changing racial composition of the population 15Deciding on a role for pharmacy16The practices of pharmacy and business16Quality of care vs. generation of profits17Business and ethical standards17The role of competition17Utilization of resources18Remaining competitive and adapting tochange18Deciding on roles for pharmacists18Evolution of the profession18The role of pharmacists as healthcareprofessionals20The role of the pharmacist within thecommunity20The pharmacist as a clinical purist21Identifying the challenges for communitypharmaciesA business world orientationChallenges in community settingsChallenges in hospital settingsHow to integrate different managerial llingRecognizing the functional areas of businessAccounting functionFinancial functionHuman resource management functionOperations management functionMarketing functionSummaryQuestions for discussionSelf-test reviewReferencesLearning objectivesThe objectives of this chapter are to assist you to be able to explain: the misconceptions about the role of business in pharmacy practicewhy a business perspective is importantchallenges for community and hospital pharmacieshow to integrate different managerial functionsthe functional areas of business.Sample chapter for Essentials of Pharmacy Management2121222323242426262627272829292930303031

14Essentials of Pharmacy ManagementKey termsAccounting functionControllingDirectingFinance functionHuman resourcesHuman resource management functionInput–output systemMarketing functionMaterial resourcesMonetary resourcesOperations management functionOrganizingPlanningRemaining competitiveStaffingUtilization of resourcesChanges in the demography of theUSAMany factors have helped to bring about an evolutionin the practice of pharmacy. Among the more important ones from a business perspective are the changesin the demography of the USA, healthcare usage andproviders, and attitudes toward the traditional role ofthe pharmacist and pharmacy.One of the most important factors affecting modern healthcare is the changing demography of theUSA. Most notably, there has been a massive distortion of the age distribution of the population, ageneral aging of the population, and a changing racialcomposition.Age distribution of the populationThe effects of the “baby boom” period followingWorld War II coupled with the “birth dearth” in theearly 1970s, when fertility rates declined dramatically,caused a pronounced shift in age distributions. The effect has often been called a “pig in a python,” similarto what happens to the shape of a large snake afterit swallows a whole pig. As the pig moves throughthe snake’s body, it distorts the shape of the snakein much the same manner as the baby boom grouphas altered the demography of the USA as it movesthrough its life cycle.The change in the distribution of the populationcan be seen in Table 2.1. The 25- to 44-year-old agegroup is declining as a percentage of the total population starting from 1990, while 45 and older is increasing as baby boomers move through this category.For pharmacy managers, it is difficult not to targetthe baby boom group as it heads toward senior status.No doubt, it will be a major concern for businessesand insurance companies in their formulation of policies for payment of their prescription drug costs. Asdescribed later in this chapter, the costs of healthcarehave grown significantly in recent decades, and asmore of the baby boomers begin to reach age 65,drug costs and usage could skyrocket. Pharmacies canexpect a restructuring of their payment systems asgovernment and the private sector try to cope.Additional implications of the distortion of thedemography are the fact that healthcare services willbe refocused on the 45- to 65-year-old age group. Thetypes of services and products they need will take ongreater importance with the sheer increase in numbersof people. Competition among pharmacies for theirbusiness will become more intense, not only becauseof the immediate dollar potential but because loyaltiesdeveloped now may extend into a time when the babyboomers become seniors.The aging of the populationThe aging, or “graying,” of America is also quiteevident. Within the population group aged 65 or moreyears, those 80 and older are making up a largerpercentage. This is shown in Table 2.2. From 1980through the year 2009, the percentage who are 85 orolder increased from 8.8 to 14.2 percent.People are living longer, and this aging process isexpected to continue further. As shown in Table 2.3,life expectancies for both females and males haverisen by 8.6 years from 1970 to 2010, and are expected to increase even more by the year 2020.As would be expected, the healthcare implicationsof this are quite significant. Seniors have more anddifferent needs for health services than do other members of the population. They visit physician officesmore frequently, require more hospital stays, use moreprescription and non-prescription drugs, and have agreater number of multiple medical problems.In addition, seniors require different services.Many have hearing or sight impairments, diminishedcognitive skills, are physically limited, etc. A community pharmacy targeting an elderly market, for example, may need wider aisles, larger signs, improvedSample chapter for Essentials of Pharmacy Management

15The role of business in pharmacy practiceTable 2.1 Age distribution of the US populationAge 2100295,753100307,0071009 years and 10–24 25–44 45–64 65 years and Median ageYears30.035.436.236.8From US Census Bureau. Statistical Abstract of the United States: 2011. Resident Population by Sex and Age: 1980 to 2009.Table 2.2 Population age 65 years and olderAge groupUnit1980%2000%2005%2009%65–74 75–84 5 years and 5,55035,07436,70439,571From US Census Bureau. Statistical Abstract of the United States: 2011. Resident Population by Sex and Age: 1980 to 2009.Table 2.3 Life 79.9201078.375.780.82020 (projection)79.577.181.9From US Census Bureau. Statistical Abstract of the United States: 2011.Resident Population Projections by Race, Hispanic-Origin Status, andAge: 2010 and 2015.lighting, and a staff that understands how to copewith the mannerisms of seniors. Similarly, the typesof prescription drugs and non-prescription productsare different from those needed to care for a youngergroup of patients. And pharmacies in the future willlikely target more of their efforts and resources on theover-65 market.Changing racial composition of thepopulationA third major change that is taking place withinthe American population is the shift in racialcomposition. Non-White populations are expected togrow rapidly, and much of the growth within the“White” category is Hispanic. This can be seen inTable 2.4.The implications of the changing racial composition of the marketplace are quite pronounced. Forsome groups, there are differences in culture, language, and product and service needs. Historically,however, it has not been economically feasible forpharmacies to target their efforts partly or completelyon a particular ethnic group. In the next severaldecades, however, some ethnic groups will be sufficiently large and geographically concentrated thatit will become financially attractive to do so. Thismeans, for example, ensuring that pharmacy staff canspeak a language other than English, the pharmacycarries non-prescription merchandise that is desiredby the particular ethnic group, and signage in thepharmacy is in a second language.Aside from the possible growth of specialty pharmacies, nearly all community and hospital pharmacies need to become more attuned to unique cultures,languages, etc. Having staff that can speak Spanish or some dialects of Chinese, carrying a range ofnon-prescription merchandise used predominantly byan ethnic group, and understanding a group’s attitudes toward the administration of drug products isSample chapter for Essentials of Pharmacy Management

16Essentials of Pharmacy ManagementTable 2.4 Population of USA by 2304,374,846307,006,5509.1One race population 856578,35325.0Black or African AmericanAmerican Indian and AlaskaNativeAsianNative Hawaiian and otherPacific IslanderPercentage change2000–2009From US Census Bureau. Statistical Abstract of the United States: 2011. Resident Population by Sex, Race, and Hispanic-Origin Status: 2010 and2015.likely to become increasingly important from bothbusiness and healthcare perspectives.Deciding on a role for pharmacyPerhaps ironically, concerns about the interface between pharmacy practice and business were not anespecially significant issue during much of the twentieth century. The “drugstore” was a business. It wasengaged in many activities in addition to dispensingprescriptions. The pharmacist and his or her employees did everything from dispensing prescriptions toselling household wares to making ice-cream sodas.To be sure, there were some who considered allnon-clinical activities to be unprofessional. Yet, whileclinical functions have always been an integral partof the business, most recognized the fact that thedrugstore owner–pharmacist served in many variedroles (Table 2.5).During the latter part of the twentieth century,greater concerns about the role of business in thepractice of pharmacy became evident. It was the likelyresult of a profession that had become more specialized owing to the complexity of the products andservices it provided.Whatever the cause, however, there are many misconceptions about what role, if any, business shouldplay in the profession. Among the most importantmisconceptions are the following: The practice of pharmacy is ethically inconsistent with good business.In business, quality of care is secondary to generating profit. Business is not a profession guided by the sametypes of ethical standards of practice that applyto pharmacy. A good pharmacist is one who is a “clinicalpurist.”The practices of pharmacy and businessOne of the more common misconceptions is that thepractice of pharmacy is ethically inconsistent withgood business. This most likely developed from theobservation of very poor business practices used bysome firms. To some pharmacists, the practice ofbusiness is symbolized by high-pressure salespeople,innocuous advertisements, and sale of products ofpoor quality.Questionable business practices do occur, but theyare not considered acceptable by most business people. Similarly, most pharmacists frown on the quality of care provided by a few of their less capablecolleagues, and on pharmacies that have been citedfor filing fraudulent prescription claims. No doubtabuses do occur, but that should not be an indictment of the professions of pharmacy or businessthemselves.As described later in this chapter, good businessand good pharmacy practice have the same objectives:to serve the patient’s needs with the resources available. From a business standpoint, the reason for this issimple: if the patient is not satisfied, he or she will notreturn. And very few businesses, including pharmacies in all practice settings, can survive without repeatsales.Sample chapter for Essentials of Pharmacy Management

The role of business in pharmacy practice17Table 2.5 The pharmacy as an input–output systemInputsProcessingOutputPharmacist’s skillsVerify eligibilityPrescriptionDrug productCheck drug appropriatenessDeliveryContainerCheck for possible drug interactionsCounselingLabelPrepare labelAnswer questionsComputer hardwareFill prescriptionSell companion productsComputer softwareRecord prescriptionInvoice payerPharmacist’s skillsPatient consultsAdvice on medication usePharmacist’s skillsMedication therapy managementRegimen for patient behaviorNon-prescription merchandiseQuality of care vs. generation of profitsAnother misconception is that in business, the quality of patient care is secondary to the generation ofprofits. Understandably, the basis for this perspectivecomes from efforts by managers in community andhospital settings to control their costs.The basic fallacy of this misconception relates tothe previous issue—if the quality of care is poor, patients will not return and future profits will be lost.From a more mercenary standpoint, the legal implications of providing substandard quality of care wouldsignificantly place profitability at risk.In fact, the generation of profits is closely linkedto the quality of care. The real issue, however, isone of what level of quality is necessary or desirable.“Care at any cost” is no longer affordable. Becausethe human, financial, and material resources of everyorganization are limited, decisions must be made asto how they are allocated. If availability of resourceswere not an issue, good business practice would notconsider anything less than the best quality of care.The realities, however, are that tradeoffs mustbe made. Unless profits can be generated to obtainresources, most for-profit and not-for-profit organizations would cease to exist. They would not havethe funds

Human resource management function Input–output system Marketing function Material resources Monetary resources Operations management function Organizing Planning Remaining competitive Staffing Utilization of resources Changesinthedemographyofthe USA Many factors have helped to bring about an evolution in the practice of pharmacy. Among the more impor-tant ones from a business