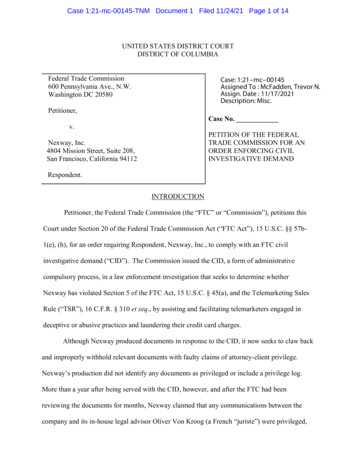

Transcription

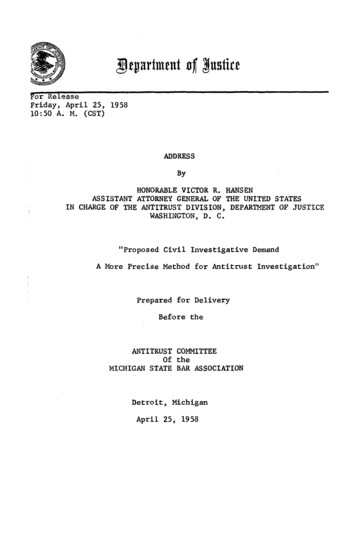

DepartmentofJusticeFor ReleaseFriday, April 25, 195810:50 A. M. (CST)ADDRESSByHONORABLE VICTOR R. HANSENASSISTANT ATTORNEY GENERAL OF THE UNITED STATESIN CHARGE OF THE ANTITRUST DIVISION, DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICEWASHINGTON, D. C."Proposed Civil Investigative DemandA More Precise Method for Antitrust Investigation"Prepared for DeliveryBefore theANTITRUST COMMITTEEOf theMICHIGAN STATE BAR ASSOCIATIONDetroit, MichiganApril 25, 1958

It is a pleasure to be with you today.Four monthsafter taking office as the head of the Antitrust Division,Department of Justice, I was requested to speak before theNew York City Bar Association.At that time I explainedthat having spent approximately six years on the bench ofthe Superior Court, California, immediately prior toassuming my present duties, required me to do much studyingto acquaint myself not only with the procedures of the office,but with the voluminous cases filed and in the process offiling, and which involved every conceivable type businessin the United States.Antitrust, you all realize, covers the entire rangeof American economic life. Thus, we have brought suits againstlead producers, 1/ shipping companies and airlines, 2/ shrimpand oyster fisherman, 3/ trailer operators, 4/ and linen1/ U. S. v. American Smelting and Refining Co., et al.Civ. 88 hyphen 249, filed October 9, 1953.2/ U. S. v. Pan American World Airways, Inc., et alCiv. 90 h yphen 259, filed January 11, 1954.3/ U. S. v. Gulf Coast Shrimpers and Oystermans Assoc. et al,Cr. 7192, filed April 1, 1953.4/ U. S. v. Nationwide Trailer Rental System, Inc., et al.Civ. W hyphen 655, filed August 28, 1953.

2service suppliers. 5/Treating even more directly thosehuman frailties to which all of us may be subject, antitrusthas moved against restraints on the manufacture of eyeglasses, 6/false teeth, 7/ and vitamin pills. 8/Just to ensure continued need for such pills, wehave attacked restrictions on the sale of alcoholic beveragesin the states that range from Maryland to Tennessee.Andriding even higher on the wave of the future, we have morerecently struck at limitations on production of sex hormones.Antitrust, I might add, is concerned not only withthe material things of life.arts as well.It covers the theatre andThus, we have proceeded against restraintsby the New York City Theatre Scenery Haulers, 9/ as well asthe International Boxing Club, 10/ The United States TrottingAssociation, 11/; and blending theatre with sport, as wellas with a sense of humor, we have filed a case against wrestling.5/6/7/8/9/10/11/U. S. v. National Linen Service Corp., et al,Cr. 20559, Civ. 5171, both cases filed April 25, 1955.U. S. v. Bausch & Lomb Optical CompanyCiv. 46 hyphen Chyphen 1332, filed July 23, 1946.U. S. V. Luxene, Inc. Civ. 66124, filed April 27, 1951.U. S. v. Merck & Co. Inc. Civ. 3159, filed October 28, 1943.U. S. v. Walton Hauling & Warehouse Corp., et al.Civ. 86hyphen286, filed July 15, 1953; Cr. 141hyphen 349,filed June 23, 1953.U. S. v. International Boxing Guild, et al.Cr. 21823, filed January 10, 1956U. S. v. The United States Trotting Association,Civ. 5233, filed March 4, 1958.

3.As you can readily see, antitrust is no esotericendeavor conducted in far-off Washington and eternallyremoved from the main stream of American living.After a little less than two years in office, I amconvinced that antitrust is a distinct American means forassuring that a competitive economy exists and is the basisof our free enterprise system.I am satisfied that the policy of vigorous and fairenforcement has resulted in more economical enforcementand more effective enforcement.I find it exceedingly difficult to know just what isof interest to the practitioner in the field of antitrustlaw.Occasionally, the audience will consist of highlyspecialized practitioners in the field of trade restrictions,and in such cases to speak generally about the Sherman Act,Sections 1 and 2, and the Clayton Act, Section 7, or aboutthe Robinson-Patman Act, is of little interest.On other occasions I met Bar Association audienceswhere the overwhelming majority are general practitioners,and only occasionally — if at all—with the antitrust laws.they come in contactIn such cases their interest isin the broader aspects of the antitrust laws rather thanin the refinement of particular points.We all realize today

4.that the antitrust laws, like the Federal tax laws,cut across major business transactions.The purchase andsale contracts, even employment contracts which you draftfor your client, price lists, methods of sale, discounts,and other allowances to customers, his acquisition of otherbusinesses by purchase or merger, the trade associationsand other industrial groups in which he participates—these and numberless other activities all have antitrustimplications.The antitrust laws are general in their terms.Mr.Chief Justice Hughes referred to them as having " * * *a generality and adaptability comparable to that foundto be desirable in constitutional provisions." 12/ So muchfor a very general statement concerning antitrust laws.This brings me to the subject which I would liketo discuss with you today - The Proposed Civil InvestigativeDemand.I have chosen this subject because I feel that theproposed legislation is of vital importance to the AntitrustDivision, and that lawyers throughout the country should beaware of the contents of this bill and of its objectives,as well as to why the Antitrust Division desires such legislation.12/288 U. S. 344, 359, 360.

5.On August 27, 1953, former Attorney GeneralHerbert Brownell, Jr. appointed a committee of distinguishedantitrust lawyers to study the antitrust laws and makerecommendations.After nineteen months of study andconsultation, this committee made a report to the AttorneyGeneral, which has been recognized as a thoughtful andconstructive analysis of the problems in this field.Oneaspect of this report dealt with the procedure for enforcementand proposed that the Department of Justice be authorized toissue a civil investigative demand in aid of its antitrustinvestigations. 13/A bill to carry out this recommendation was presentedto the Congress in July, 1955.The Economic Report of thePresident to Congress in 1956, among other antitrust legislationrecommended, strongly urged that the Attorney General beempowered to issue a civil investigative demand.The proposed bill, which has safeguards of the typerecommended by the Committee, would provide for issuance bythe Attorney General or the Assistant Attorney General incharge of the Antitrust Division, of civil investigative demandswhenever they have reason to believe that any person may be inpossession, custody or control of any documentary material13/ Report of the Attorney General's National Committee to Studyh rough 349 (1955).the AntiTrust Laws, pp. 343 t

6.bearing on any antitrust investigation.Each demandwould contain a statement of the statute which allegedlyis being violated and a description of the class or classesof documentary material to be produced with such definitenessand certainty as to permit such material to be fairly identified.It also would prescribe a return date providing a reasonabletime within which the evidence demanded may be assembled andproduced, and identify the custodian to whom such evidenceis to be deliveredThe bill would prohibit any requirement which wouldbe held unreasonable if contained in a court-issued subpoenaduces tecum in aid of a grand jury investigation.It alsowould bar any requirement for production of any documentaryevidence which the recipient can show would be privilegedfrom disclosure if demanded by a subpoena duces tecum.Provision is also made to:1.Permit the Department to ask a Federal DistrictCourt to issue an order to enforce a demand fordocuments.2.Permit a person upon whom a demand is served bythe Department to petition a Federal DistrictCourt within 20 days of such service for an ordermodifying or setting aside such a demand.

7.Any disobedience of any final order by a court would bepunishable as a contempt.The bill also provides for criminal penalties notexceeding five thousand dollars fine, five years' imprisonment,or both, for anyone convicted of wilfully removing, concealing,withholding, destroying, mutilating, altering, or by anyother means falsifying any material in his possession, custodyor control, with the intent to avoid, evade, prevent, orobstruct compliance in whole or in part with any civilinvestigative demand.The need for such a bill seems clear.law, the Department has no such power.Under presentAs matters stand now,the Department has only two alternatives:First, it can seekthe voluntary cooperation of those firms and persons underinvestigation; Second, it can resort to the use of a grandjury.The first of these alternatives has sometimes beenfound satisfactory, for many parties under investigationhave voluntarily thrown open their files to governmentinvestigators or furnished specifically designated information.Others have not.Under these circumstances we have noalternative except to proceed by way of grand jury.TheDepartment should not be required, in order to enforce the law,

8.to subject every person suspected of a law violation toa grand jury investigation.And from my experience Ican say that many others agree with me, because as soonas subpoenas duces tecum are issued those persons who mayhave been involved in a purely civil matter come in to opentheir files or furnish information.In pre-complaint merger investigations this demandis particularly important, for Section 7 has no criminalsanction.Accordingly, we cannot resort to grand jury tosecure documents from companies under investigation forSection 7 violation, even if this procedure could bring usthe information in the limited time between knowledge ofthe merger and its consummation.So it is that enactment ofthis civil investigative demand is vital to more effectiveanti-merger work.While situations have arisen where grand juryproceedings were used to secure evidence upon which a civilcase was later based, these have been few in number.Themajority of civil cases are based upon the Government'sown investigation.It is in these essentially civil casesthat the civil investigative demand is needed and in which Ibelieve it would provide an effective enforcement weapon.

9.The proposed civil investigative demand would permitthe Government to examine unprivileged correspondence andbusiness records of the party under investigation before asuit is brought.If it is determined that the proof doesnot support the alleged violation, the matter would, of course,be dropped.If, on the other hand, it is decided to proceed,the Government would not be required to rely upon secondarysources for its information and would then be in a much betterposition to frame an adequate complaint.The proposed civil investigative demand would be subjected toall of the safeguards which now attend a subpoena.A personupon whom a demand is made would be authorized to proceed beforethe District Court of his own district to modify or vacate anydemand believed to be unreasonable in scope, inadequate indescription of material demanded, or lacking in specificity.The documents produced under the demand would be held by acustodian in the Department of Justice; they would not beavailable to any person except the person from whom they weretaken, officers of the Antitrust Division or the Federal TradeCommission.They would not be subject to use except in theinvestigation described in the demand or an ensuing investigationbefore a grand jury, by the Antitrust Division, or by the

10.Federal Trade Commission.At the time this recommendation was made, there wassome dissent among the members of the Attorney General'sCommittee and I am sure other members of the bar also hadsimilar doubts.It was contended that t h i s grant of powerto an executive officer disregarded the separation of theexecutive and judicial power; that an executive officerwith no quasi-judicial functions should not be authorizedto use a procedure so analogous to a court issued process.It is respectfully pointed out, however, that this wouldnot be the first time such a power was granted.For example,the Attorney General of the State of New York has such powerunder Executive Law, Section 63.Certain agencies of theFederal Government have actual subpoena power, with theright to apply to the district courts to enforce compliance.The Securities and Exchange Commission, for example, mayrequire the production of any books and papers which theCommission deems relevant or material to its investigation. 14/Likewise, the Federal Trade Commission may compel theproduction of documentary evidence and may invoke the aid ofany Federal Court in securing the production of such14/15 U. S. C. Sec. 78u.

11.evidence. 15/To those persons who feel that the civil investigativedemand may be abused by the executive officer, I believethe final answer is that the reviewing power of the courtaffords a true safeguard which could be utilized by theperson under investigation to curb any abuse on the partof the officer and to secure a prompt remedy upon appropriateapplication to the district court.Other critics of the proposed civil investigativedemand urge that the antitrust laws are essentiallycriminal and should be enforced as such.This objectionoverlooks the fact that antitrust enforcement is bothcriminal and civil, as well as the further fact that theproposed civil investigative demand could only be usedfor purposes of a civil proceeding.Antitrust laws are among the most complex anddifficult to enforce.Every possible procedural flexibilityshould be made available in aid of their enforcement.Major cases usually involve voluminous documentary material.The use and expeditious presentation of this material willbe more effective if before the filing of a case the material15/ 15 U. S. C. Sec. 49,

12.is made available by means of the proposed civil investigativedemand.In view of the evident need for the early enactmentof this bill, it is my hope that Congress will move promptlyto act on our recommendations.Fortunately for our formof government, all groups have some voice, and there isalmost always struck some sort of balance, so that no onevoice is too persuasive.In the antitrust field, however,I am not so sure that this balance is always attained.Support for our efforts, I suggest, can come only with themore widespread realization of the popular stake in effectiveantitrust enforcement.So it is that meetings like today'sincrease informed discussion of basic problems and servea vital public service.Now I would like to close with a few thoughts onthe role antitrust plays in preserving a healthy nationaleconomy that is so important to all of us.In 1776, Adam Smith's "Wealth of Nations," comparingBritain and the United States, noted:But though North America is not yet so rich asEngland, it is much more thriving, and advancingwith much greater rapidity to the furtheracquisition of riches.Since that day hardly a year has passed withoutsome like exclamation of wonder from students of economics.

13For example, in 1939, Michael Chevalier, in his "Society,Manners and Politics in the United States," remarkedon the difference between his own France and what hesees here:An American's business, Chevalier says, is alwaysto be on edge lest his neighbor get there beforehim . . . Industry has become a veritable battlefield. . . Unlimited competition (has) become the solelaw of labor, everyone being his own master.These observations are firmly rooted in therealities of our national income statistics.In 1952the average income per person in the United States wastwice that of the Swiss citizen, three times that ofthe Englishman or Frenchman, or Belgian, six times thatof the Western German.National income of necessity restsupon national production, our productivity.In America we produce one-third of the total goodsin the world and one-half the manufactured goods withone-fifteenth of the land area of the world, one-fifteenthof the people of the world, and one-fifteenth of thenational resources of the world.Perhaps influenced by this striking comparison, anoted Swiss political economist, William E. Rappard, concludedin his study, "The Secret of American Prosperity," published

14as recently as May, 1955, "that the United Statestoday enjoys a much greater average income than anyother nation.The material standard of living is,therefore, by far the highest in the world."Seeking thereason for this, Mr. Rappard wrote Mr. John S. Crout,Director of the renowned Battelle Institute.ExplainingAmerican growth, Mr. Crout reasoned:Antitrust has compelled corporate managements toreconsider their position. They realized thatthey were required to compete, but had no hopeof ever establishing a monopoly.Under these circumstances, they accepted theconcept of true competition and directed theirenergies and efforts no ways and means of increasingtheir profits by expansion of their volume of business.In essence, this meant that each management set outto do a better job of producing, selling anddistributing its products than its competitors. 16/A like conclusion was reached by a British studyteam that recently visited this country.As a result ofthe Marshall Plan, international study centers wereorganized to study the reasons for the superior productivityof American industry."The Anglo-American Council onProductivity" was set up.It was responsible for organizingBritish teams of managers, technicians, and trade unionists,which went to the United States to see what methods used16/ William E. Rappard, The Secret of American Prosperity,(1955), p. 67.

15.there could be adapted to the needs of Great Britain.Sixty-six teams had made the trip by late 1952.Theypresented reports which were practically unanimous.Lest you think I might be biased in reporting theirconclusions, let me read you what an American newspaperreported under a London dateline in late 1954, as a resultof the return of one of the latest teams.The New YorkTimes headline read:Productivity Team Lays U. S. Output Supremacy Largelyto Sherman, Clayton Acts.Hits Own Country's LawParliament Urged to Act on Manufacturer Pacts ThatEnd CompetitionThat newspaper's account went on:The praise for the Sherman and Clayton AntitrustActs was included in the industrial engineers'report because, according to members of the group,"it was the answer we kept getting when we askedAmericanswhat was the source of the competitivenessin their economy," The group's secretary . . .remarked that " . . . the monopolies issue hasbecome a part of the public morality of the UnitedStates; it is enforced by public opinion."And so we see the importance that antitrust enforcementassumes, in the eyes of others.It has withstood thecrucible not only of time, but of study.Today it stands

16.as one of the prime supports for our prosperous andfree competitive economy.indeed, all Americans —In its preservation you—have a vital stake.With this thought uppermost, I thank you for thischance to be with you, and wish the work of thisorganization well.

this civil investigative demand is vital to more effectiv e anti-merger work. While situations have arisen where grand jur y proceedings were used to secure evidence upon which a civi l case was later based, these have been few in number. Th e majority of civil cases are based upon the Government' s own investigation.