Transcription

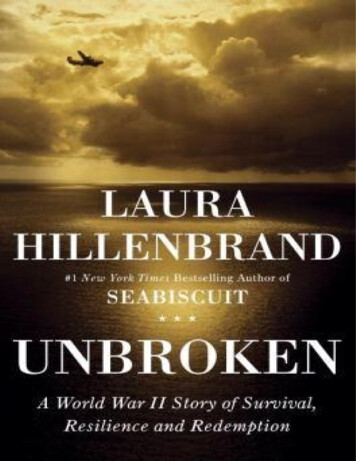

Also by Laura HillenbrandSEABISCUIT

Copyright 2010 by LauraHil enbrandAl rights reserved.Published in the United Statesby Random House, an imprintof The Random HousePublishing Group, a divisionof Random House, Inc., NewYork.RANDOMHOUSEand

colophonaretrademarksofHouse, Inc.registeredRandomLIBRARY OF CONGRESSCATALOGING-INPUBLICATION DATAHil enbrand, Laura.Unbroken : a World War Istory of survival, resilience,and redemption / Laura Hilenbrand.

p. cm.eISBN: 978-0-679-60375-71. Zamperini, Louis, 1917– 2.World War, 1939–1945—Prisonersandprisons,Japanese. 3. Prisoners of war—United States—Biography.4. Prisoners of war—Japan—Biography. 5. World War,1939–1945—Aerialoperations, American. 6.World War, 1939–1945—

Campaigns—Pacific Area. 7.United States. Army AirForces. Heavy BombardmentGroup, 307th. 8. Longdistancerunners—UnitedStates—Biography. I. Title.D805.J3Z364 2010940.54′7252092—dc22[B] 2010017517www.atrandom.com

v3.1For the wounded and the lostWhat stays with you latestand deepest? of curiouspanics,Of hard-fought engagementsor sieges tremendous whatdeepest remains?—WaltWhitman,Wound-Dresser”“The

CONTENTSCoverOther Books by This AuthorTitle PageCopyright

DedicationMapEpigraph

PrefacePART IChapter 1. The One-BoyInsurgencyChapter 2. Run Like MadChapter 3. The TorranceTornado

ChapterGermany4.PlunderingChapter 5. Into War

PART IChapter 6. The Flying CoffinChapter 7. “This Is It, Boys”Chapter 8. “Only the LaundryKnew How Scared I Was”Chapter 9. Five Hundred andNinety-four Holes

Chapter 10. The Stinking SixChapter 11. “Nobody’s Goingto Live Through This”

PART IIChapter 12. DownedChapter 13. Missing at SeaChapter 14. ThirstChapter 15. Sharks and BuletsChapter 16. Singing in the

CloudsChapter 17. Typhoon

PART IVChapter 18. A Dead BodyBreathingChapter 19. Two HundredSilent MenChapter 20.HirohitoFartingChapter 21. Belieffor

Chapter 22. Plots AfootChapter 23. MonsterChapter 24. HuntedChapter 25. B-29Chapter 26. MadnessChapter 27. Fal ing DownChapter 28. Enslaved

Chapter 29. Two Hundredand Twenty PunchesChapter 30. The Boiling CityChapter 31.StampedeTheNakedChapter 32. Cascades of PinkPeachesChapter 33. Mother’s Day

PART VChapter 34. The ShimmeringGirlChapter 35. Coming UndoneChapter 36. The Body on theMountainChapter 37. Twisted Ropes

Chapter 38. A BeckoningWhistleChapter 39. Daybreak

EpilogueAcknowledgmentsNotesAbout the Author

PREFACEALL HE COULD SEE, INEVERY DIRECTION, WASWATER. It was June 23,1943. Somewhere on theendless expanse of the PacificOcean, Army Air Forcesbombardier and Olympicrunner Louie Zamperini layacross a smal raft, driftingwestward. Slumped alongside

him was a sergeant, one of hisplane’s gunners. On aseparate raft, tethered to thefirst, lay another crewman, agash zigzagging across hisforehead.Theirbodies,burned by the sun and stainedyel ow from the raft dye, hadwinnowed down to skeletons.Sharks glided in lazy loopsaround them, dragging theirbacks along the rafts, waiting.The men had been adrift for

twenty-seven days. Borne byan equatorial current, theyhad floated at least onethousand miles, deep intoJapanese-control ed waters.The rafts were beginning todeteriorate into jel y, andgave off a sour, burning odor.The men’s bodies werepocked with salt sores, andtheir lips were so swol en thatthey pressed into their nostrilsand chins. They spent theirdays with their eyes fixed on

the sky, singingChristmas,”“Whitemuttering about food. No onewas even looking for themanymore. They were alone onsixty-four mil ion squaremiles of ocean.A month earlier, twenty-sixyear-old Zamperini had beenone of the greatest runners inthe world, expected by manyto be the first to break the

four-minute mile, one of themost celebrated barriers insport. Now his Olympian’sbody had wasted to less thanone hundred pounds and hisfamous legs could no longerlift him. Almost everyoneoutside of his family hadgiven him up for dead.On that morning of thetwenty-seventh day, the menheardadistant,deepstrumming. Every airman

knew that sound: pistons.Their eyes caught a glint inthe sky—a plane, highoverhead. Zamperini firedtwo flaresand shookpowdered dye into the water,enveloping the rafts in acircle of vivid orange. Theplane kept going, slowlydisappearing.Themensagged. Then the soundreturned, and the plane cameback into view. The crew hadseen them.

With arms shrunken to littlemore than bone and yel owedskin, the castaways wavedand shouted, their voices thinfrom thirst. The planedropped low and sweptalongside the rafts. Zamperinisaw the profiles of thecrewmen, dark against brightblueness.There was a terrific roaringsound. The water, and therafts themselves, seemed to

boil. It was machine gun fire.This was not an Americanrescue plane. It was aJapanese bomber.The men pitched themselvesinto the water and hungtogether under the rafts,cringing as bul ets punchedthrough the rubber and slicedeffervescent lines in the wateraround their faces. The firingblazed on, then sputtered outas the bomber overshot them.

The men dragged themselvesback onto the one raft thatwas stil mostly inflated. Thebomber banked sideways,circling toward them again.As it leveled off, Zamperinicould see the muzzles of themachine guns, aimed directlyat them.Zamperini looked toward hiscrewmates. They were tooweak to go back in the water.As they lay down on the floor

of the raft, hands over theirheads, Zamperini splashedoverboard alone.Somewhere beneath him, thesharks were done waiting.They bent their bodies in thewater and swam toward theman under the raft.

Courtesy of Louis Zamperini.Photo of original image byJohn Brodkin .OneThe One-Boy InsurgencyINTHEPREDAWNDARKNESS OF AUGUST26, 1929, IN THE backbedroom of a smal house inTorrance,California,a

twelve-year-old boy sat up inbed, listening.There was a sound comingfrom outside, growing everlouder. It was a huge, heavyrush, suggesting immensity, agreat parting of air. It wascoming from directly abovethe house. The boy swung hislegs off his bed, raced downthe stairs, slapped open theback door, and loped onto thegrass.Theyardwas

otherworldly, smothered inunnatural darkness, shiveringwith sound. The boy stood onthe lawn beside his olderbrother, head thrown back,spel bound.The sky had disappeared. Anobject that he could see onlyin silhouette, reaching acrossa massive arc of space, wassuspended low in the air overthe house. It was longer thantwo and a half footbal fields

and as tal as a city. It wasputting out the stars.What he saw was the Germandirigible Graf Zeppelin . Atnearly 800 feet long and 110feet high, it was the largestflying machine ever crafted.More luxurious than nces, built on a scale thatleft spectators gasping, it was,in the summer of ’29, the

wonder of the world.The airship was three daysfrom completing a globe. The journey had begunon August 7, when theZeppelin had slipped itstethers in Lakehurst, NewJersey, lifted up with a long,slow sigh, and headed forManhattan. On Fifth Avenuethat summer, demolition was

soon to begin on the WaldorfAstoria Hotel, clearing theway for a skyscraper ofunprecedented proportions,the Empire State Building. AtYankee Stadium, in theBronx, players were debutingnumbered uniforms: LouGehrig wore No. 4; BabeRuth, about to hit his fivehundredth home run, woreNo. 3. On Wal Street, stockprices were racing toward anal -time high.

After a slow glide around theStatue of Liberty, theZeppelin banked north, thenturned out over the Atlantic.In time, land came belowagain: France, Switzerland,Germany. The ship passedoverNuremberg,wherefringe politician Adolf Hitler,whose Nazi Party had beentrouncedinthe1928elections, had just delivered aspeechtoutingselectiveinfanticide. Then it flew east

of Frankfurt, where a Jewishwoman named Edith Frankwas caring for her newborn, agirl named Anne. Sailingnortheast,theZeppelincrossed over Russia. Siberianvil agers, so isolated thatthey’d never even seen atrain, fel to their knees at thesight of it.On August 19, as some fourmil ion Japanese wavedhandkerchiefs and shouted

“Banzai!”theZeppelincircled Tokyo and sank onto alanding field.Four days later, as theGermanandJapaneseanthems played, the ship roseinto the grasp of a typhoonthat whisked it over thePacific at breathtaking speed,toward America. Passengersgazing from the windows sawonly the ship’s shadow, folowing it along the clouds

“like a huge shark swimmingalongside.” When the cloudsparted,thepassengersglimpsed giant creatures,turning in the sea, that lookedlike monsters.On August 25, the Zeppelinreached San Francisco. Afterbeing cheered down theCalifornia coast, it slidthrough sunset, into darknessand silence, and acrossmidnight. As slow as the

drifting wind, it passed overTorrance, where its onlyaudience was a scattering ofdrowsy souls, among themthe boy in his pajamas behindthe house on GramercyAvenue.Standing under the airship,his feet bare in the grass, hewas transfixed. It was, hewould say, “fearful ybeautiful.” He could feel therumble of the craft’s engines

til ing the air but couldn’tmake out the silver skin, thesweeping ribs, the finned tail.He could see only theblackness of the space itinhabited. It was not a greatpresence but a great absence,a geometric ocean ofdarkness that seemed to swalow heaven itself.——The boy’s name was Louis

Silvie Zamperini. The son ofItalian immigrants, he hadcome into the world in Olean,New York, on January 26,1917, eleven and a halfpounds of baby under blackhair as coarse as barbed wire.His father, Anthony, had beenliving on his own since agefourteen, first as a coal minerand boxer, then as aconstruction worker. Hismother, Louise, was a petite,playful beauty, sixteen at

marriage and eighteen whenLouie was born.In their apartment, whereonly Italian was spoken,Louise and Anthony cal edtheir boy Toots.From the moment he couldwalk, Louie couldn’t bear tobe corral ed. His siblingswould recal him careeningabout, hurdling flora, fauna,and furniture.

The instant Louise thumpedhim into a chair and told himto be stil , he vanished. If shedidn’t have her squirmingboy clutched in her hands,she usual y had no idea wherehe was.In 1919, when two-year-oldLouie was down withpneumonia, he climbed outhisbedroomwindow,descended one story, andwent on a naked tear down

the street with a policemanchasing him and a crowdwatching in amazement. Soonafter, on a pediatrician’sadvice, Louise and Anthonydecided to move theirchildren to the warmer climesof California. Sometime aftertheir train pul ed out of GrandCentral Station, Louie bolted,ran the length of the train, andleapt from the caboose.Standing with his franticmother as the train rol ed

backward in search of the lostboy, Louie’s older brother,Pete, spotted Louie strol ingup the track in perfectserenity. Swept up in hismother’s arms, Louie smiled.“I knew you’d come back,”he said in Italian.In California, Anthony landeda job as a railway electricianand bought a half-acre fieldon the edge of Torrance,population 1,800. He and

Louise hammered up a oneroom shack with no runningwater, an outhouse behind,and a roof that leaked sobadly that they had to keepbuckets on the beds.With only hook latches forlocks, Louise took to sittingby the front door on an applebox with a rol ing pin in herhand, ready to brain anyprowlers who might threatenher children.

There, and at the GramercyAvenue house where theysettled a year later, Louisekept prowlers out, butcouldn’t keep Louie in hand.Contesting a footrace across abusy highway, he just missedgetting broadsided by ajalopy. At five, he startedsmoking,pickingupdiscarded cigarette buttswhilewalkingtokindergarten.Hebegandrinking one night when he

was eight; he hid under thedinner table, snatched glassesof wine, drank them al dry,staggered outside, and fel intoa rosebush.Ononeday,Louisediscovered that Louie hadimpaled his leg on a bamboobeam; on another, she had toask a neighbor to sew Louie’ssevered toe back on. WhenLouie came home drenchedin oil after scaling an oil rig,

diving into a sump wel , andnearly drowning, it took a galon of turpentine and a lot ofscrubbing before Anthonyrecognized his son again.Thril ed by the crashing ofboundaries,Louiewasuntamable. As he grew intohis uncommonly clever mind,mere feats of daring were nolongersatisfying.InTorrance,aone-boyinsurgency was born.

——If it was edible, Louie stole it.He skulked down al eys, a rolof lock-picking wire in hispocket. Housewives whostepped from their kitchenswould return to find that theirsuppers had disappeared.Residents looking out theirback windows might catch aglimpse of a long-legged boydashing down the al ey, awhole cake balanced on his

hands. When a local familyleft Louie off their dinnerparty guest list, he broke intotheir house, bribed their GreatDane with a bone, andcleaned out their icebox. Atanother party, he abscondedwith an entire keg of beer.When he discovered that thecooling tables at Meinzer’sBakery stood within an arm’slength of the back door, hebegan picking the lock,snatching pies, eating until he

was ful , and reserving therest as ammunition forambushes. When rival thievestook up the racket, hesuspended the stealing untilthe culprits were caught andthe bakery owners droppedtheir guard. Then he orderedhis friends to rob Meinzer’sagain.It is a testament to the contentof Louie’s childhood that hisstories about it usual y ended

with “ and then I ran likemad.” He was often chasedby people he had robbed, andat least two people threatenedto shoot him. To minimizethe evidence found on himwhen the police habitual ycame his way, he set up lootstashing sites around town,including a three-seater cavethat he dug in a nearby forest.Under the Torrance Highbleachers, Pete once found astolen wine jug that Louie

h

Unbroken : a World War I story of survival, resilience, and redemption / Laura Hil enbrand.