Transcription

WJ CWorld Journal ofCardiologyWorld J Cardiol 2016 January 26; 8(1): 41-56ISSN 1949-8462 (online)Submit a Manuscript: http://www.wjgnet.com/esps/Help Desk: http://www.wjgnet.com/esps/helpdesk.aspxDOI: 10.4330/wjc.v8.i1.41 2016 Baishideng Publishing Group Inc. All rights reserved.REVIEWSurgical perspectives in the management of atrialfibrillationKaterina Kyprianou, Agamemnon Pericleous, Antonio Stavrou, Inetzi A Dimitrakaki, Dimitrios Challoumas,Georgios DimitrakakisKaterina Kyprianou, Department of General Surgery, NorthBristol NHS trust, Southmead Hospital, Bristol BS10 5NB,United KingdomTelephone: 44-29-20745160Received: May 27, 2015Peer-review started: May 29, 2015First decision: July 10, 2015Revised: August 8, 2015Accepted: November 17, 2015Article in press: November 25, 2015Published online: January 26, 2016Agamemnon Pericleous, Antonio Stavrou, School ofMedicine, Heath Park Campus, Cardiff CF14 4XW, UnitedKingdomInetzi A Dimitrakaki, Department of Cardiology, MetropolitanHospital of Athens, 18547 Faliro, GreeceDimitrios Challoumas, Department of Respiratory Medicine,Gloucestershire Royal Hospital, Gloucester GL1 3NN, UnitedKingdomAbstractAtrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common cardiacarrhythmia and a huge public health burden associatedwith significant morbidity and mortality. For decades anincreasing number of patients have undergone surgicaltreatment of AF, mainly during concomitant cardiacsurgery. This has sparked a drive for conducting furtherstudies and researching this field. With the cornerstoneCox-Maze III “cut and sew” procedure being technicallychallenging, the focus in current literature has turnedtowards less invasive techniques. The introductionof ablative devices has revolutionised the surgicalmanagement of AF, moving away from the traditionalsurgical lesions. The hybrid procedure, a combination ofcatheter and surgical ablation is another promising newtechnique aiming to improve outcomes. Despite theincreasing number of studies looking at various aspectsof the surgical management of AF, the literature wouldbenefit from more uniformly conducted randomisedcontrol trials.Georgios Dimitrakakis, Department of Cardiothoracic Sur gery, University Hospital of Wales, Cardiff CF14 4XW, UnitedKingdomAuthor contributions: Kyprianou K and Dimitrakakis Gdesigned research; Kyprianou K performed research; KyprianouK wrote the paper; Dimitrakakis G edited the paper; PericleousA performed the final review and editing; Pericleous A, StavrouA, Dimitrakaki IA and Challoumas D contributed to part of theinitial draft of the paper.Conflict-of-interest statement: There is no conflict of interestassociated with any of the authors that have contributed to thispublication.Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which wasselected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by externalreviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the CreativeCommons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license,which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon thiswork non-commercially, and license their derivative works ondifferent terms, provided the original work is properly cited andthe use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/Key words: Atrial fibrillation; Cardiac surgery; Surgicalmanagement; Surgical ablation; Minimally invasive The Author(s) 2016. Published by Baishideng PublishingGroup Inc. All rights reserved.Correspondence to: Georgios Dimitrakakis, MD, MSc,Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery, University Hospital ofWales, Heath Park Campus, Cardiff CF14 4XW,United Kingdom. gdimitrakakis@yahoo.comWJC www.wjgnet.comCore tip: The surgical management of atrial fibrillation(AF) is a rapidly developing field. Existing surgical41January 26, 2016 Volume 8 Issue 1

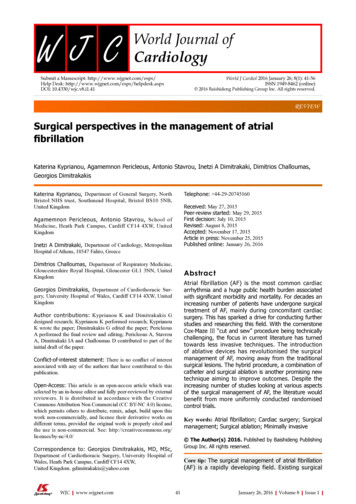

Kyprianou K et al . Surgical management of atrial fibrillationtechniques are constantly evolving in order to achievemore minimally invasive procedures. Additionally,the relatively new ablative modalities are beingincrea singly used, either alone or in conjunction withsurgical techniques; attempting overall better andless invasive results. This review looks at the currentsurgical techniques and ablative modalities available formanaging AF, where each section is re-enforced withthe current most up to date guidelines on the use ofeach of these modalities.ablative devices using various energy sources, as wellas less surgically invasive Cox-Maze lesions allowing[2]replacement of incisions with ablation lines . Thereis still on-going research and development of newtechniques, within this rapidly evolving field.AF BACKGROUND AND DEFINITIONSElectrophysiological basis of AF[9]In 1998, Haïssaguerre et al made an importantdiscovery regarding the origin of atrial ectopic beats inparoxysmal AF. At the time it was known that chronic AFwas the result of re-entrant circuits, though no informa tion was available about its origin.The spontaneous initiation of AF was studied usingintra-cardiac monitoring, angiography and fluoroscopylooking specifically at the electrical activity preceding theonset of AF. A total of 69 foci were identified as beingresponsible for the origin of atrial ectopic beats, in astudy of 45 patients. The striking majority (94%) of thefoci were found to be in the pulmonary veins with othersincluding the right and left atria. Radiofrequency catheterablation was subsequently utilised to ablate those fociin order to abolish spontaneous depolarisation. Sinusrhythm was achieved and maintained in 28 patients[9](62%) at a follow up period of 8 6 mo . This discoveryled to the pulmonary vein isolation (PVI) approach.The identification of abnormal depolarisation foci,helped in understanding the origin and development ofAF. It became apparent that ectopic atrial depolarisationis responsible for the initiation of AF, whilst macro reentrant circuits are responsible for its propagation (Figure[10]1) .Kyprianou K, Pericleous A, Stavrou A, Dimitrakaki IA,Challoumas D, Dimitrakakis G. Surgical perspectives in themanagement of atrial fibrillation. World J Cardiol 2016; 8(1):41-56 Available from: URL: http://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8462/full/v8/i1/41.htm DOI: Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common cardiacarrhythmia seen in clinical practice and it has beenassociated with substantial morbidity and mortality.The lifetime risk of AF between the ages of 40-95 is 1[1]in 4, as demonstrated by the Framingham study . Inthe general population AF has been shown to occur in[2]around 1%-2% .Patients suffering from AF are at risk of throm boembolic events, including stroke leading to disabilityor death. One out of every five strokes is secondary toAF, with those resulting from AF being more disabling[1,3]and having increased clinical significance .The first-line treatment of AF has traditionally beenanti-arrhythmic drugs, whether attempting rate andor rhythm control. However, long-term anticoagulationis not without risks as it can interfere with quality oflife and increase morbidity. There is still considerablevariation in the pharmacological treatments of AF in[2]clinical practice .Catheter based ablation is an alternative to medicaltherapy, as a minimally invasive intervention which can[4]provide relatively good results .The role of surgery in the management of AF hasbeen introduced following the ground-breaking “Maze”[5]procedure described and developed by Cox et al in aseries of publications. The “Maze” procedure has been[3-8]the cornerstone of surgical management of AF . TheCox-Maze III procedure is regarded as the gold-standardsurgical treatment of AF having the highest successrates; greater than or equal to 90% long-term freedom[4,9,10]from AF. However, the procedure is highly invasiveand technically difficult, requiring a high level of surgical[9]expertise, thus limiting its use to a few specialist centres .These limitations have fuelled further research inthe field of surgical management of AF with a view todevelop less invasive but equally effective alternativetechniques.This has led to the development and use of multipleWJC www.wjgnet.comDefinition and classification of AFAF is defined as a supra-ventricular arrhythmia whereasynchronous atrial activation occurs, leading to wor [2,4,11]sening atrial mechanical function.According to the definitions given by ACC/ESC/AHA 2006, Society of thoracic surgery (STS), ESCand EACTS clinical guidelines committee, there arefive types of AF. These are defined as: First diagnosis,paroxysmal, persistent, long-standing persistent andpermanent AF (Table 1).AF can also be classified as primary or secondaryaccording to its origin. Primary AF occurs in patients withno underlying cardiac disease whilst secondary AF occursas a result of pre-existing cardiac disease. This hasimplications when looking at the surgical managementof AF. Whilst patients with secondary AF benefit fromconcomitant treatment alongside other cardiac surgicalprocedures, catheter ablation alone is a more suitable[12-15]treatment modality for paroxysmal primary AF.SURGICAL MANAGEMENT OF AFCorrect nomenclature for surgical procedures used inAF managementAccording to 2012 HRS/EHRA/ESC guidelines the term42January 26, 2016 Volume 8 Issue 1

Kyprianou K et al . Surgical management of atrial fibrillationTable 1 The five types of atrial fibrillation as classified by European Heart Rhythm Association and European Association For CardioThoracic SurgeryType of AFFirst diagnosisParoxysmalPersistentLong standing persistentPermanentDurationDefinition48 hFirst episode of AF irrespective to duration or severitySelf-terminating (usually within 48 h); may continue for up to 7 d. After 48 h it is unlikely that spontaneousconversion will occurAnticoagulation must be consideredRequires termination by cardio-eversion with drugs or direct currentRhythm control strategyPresence of arrhythmia is accepted and rhythm control interventions are not pursued1 7d 1 yr-1In case of rhythm control interventions, the permanent AF should be re-designated as long standing persistent AF. AF: Atrial fibrillation.Depolarisationfrom ectopic foci56Transmission rical activityAtrial ectopicbeatsTermination ofabnormal activity3aChronic AFSinus rhythm43bPresence ofmacro re-entrantpathwaysParoxysmal AFContinuedabnormaldepolarisationFigure 1 Electrophysiological basis of paroxysmal and chronic atrial fibrillation. AF: Atrial fibrillation.“Maze” procedure should only be used to refer to theCox-Maze III lesion set. The above term should not beused for other less extensive lesion sets. Furthermore,the suggested terminology for ablative procedures isas follows: (1) full Cox-Maze lesion set; (2) left atrial[4,14]appendage (LAA) lesion set; and (3) PVI.shortly followed which overcame the limitations of theprevious two procedures. Atrial transport function waspreserved allowing depolarisation from sinoatrial nodeto atrioventricular node for efficient atrial contraction.CM-III achieved 93% freedom from AF during an 8.5year follow up, with successful cardioeversion of allcases on one anti-arrhythmic drug. Additionally, theneed for pacemaker was abolished and recurrence of[7-10]AF reduced. Equally encouraging results from theCM-III were generated by the Cleveland Clinic and Mayo[16,17]Clinic.Despite its high success rates the procedure re mained technically challenging and highly invasive.A median sternotomy and cardiopulmonary bypass(CPB) is required for CM-III, limiting its use to patientsundergoing concomitant heart surgery, as it is deemedto be too invasive to be solely performed for AF treat ment.The Cox-Maze “cut and sew” procedure[6]Cox-Maze I and II: Cox et al first described theCox-Maze procedure in 1991. The Cox-Maze I (CM-I)procedure was initially developed, consisting of a setof lesions generating an “electrical maze” through theatria. The linked atrial segments were created surgicallyby cutting and sewing in order to interrupt and eliminate[7-10]macro re-entrant circuits. The Maze I procedurehad several limitations including left atrial dysfunctionand failure to generate sinus tachycardia on exertion.The Cox-Maze II (CM-II) procedure was subsequentlydeveloped aiming to overcome those limitations. InCM-II a revised lesion set was used, in an attempt toimprove conduction between the atria. However, thisled to a technically more challenging procedure with the[7-10]same drawbacks as CM-I.The Cox-Maze IV: A few years later, the Cox-Maze IV(CM-IV) was developed initially described by Gaynor et[18]alin 2004. A different lesion set to CM-III was usedand the traditional “cut and sew” technique was replacedwith the use of ablative devices. Namely, the combineduse of bipolar radiofrequency ablation together withCox-Maze III: The Cox-Maze III (CM-III) procedureWJC www.wjgnet.com43January 26, 2016 Volume 8 Issue 1

Kyprianou K et al . Surgical management of atrial fibrillationcryoblation was used in that study. Moreover, CM-IVhad the added advantage of being technically simplerthan CM-III, meaning that it could be used in a greaternumber of centres. The lesion set used was similar to[18,19]CM-III and it still had to be performed under CPB.Widespread variation has been observed in thelesion sets used to treat AF. Since the publication ofCM-III the lesion sets have been altered slightly in CMIV and are continuously being altered in the currentliterature. The main reason for the constant alterationof the lesion sets is that surgeons are striving to achieveminimally invasive procedures, with the best clinical[12]outcomes possible .ischaemic stroke and another had a TIA. Twelve percentof the patients had subsequent self-reported strokes onfollow-up done via a questionnaire.[28]Kanderian et al(2008) demonstrated that 55%of 137 patients who underwent LAA closure had asuccessful procedure. Eleven percent of the patientsthat had a successful closure had a subsequent strokeor TIA compared to 15% of those with unsuccessfulprocedure. These results were nevertheless found to benon-significant.[29]García-Fernández et al(2003) looked at 205patients undergoing mitral valve surgery, with 58 ofthem having LAA ligation. Successful ligation was seenin 89.7% of patients. Absence of LAA ligation was foundto be an independent predictor of thromboembolismfollowing mitral valve surgery. Systemic emboli occurredmore frequently in the group of patients that did notreceive ligation.[30]Contrasting the above studies, Almahameed et al(2007) found a significantly increased rate of stoke inpatients with LAA occlusion, looking at 136 patients thatunderwent LAA ligation during mitral valve surgery.The above studies demonstrate the heterogeneity ofexisting results when looking at LAA exclusion. Successrate is variable between the studies, ranging from 55%to 93%. According to the EACTS guidelines, there isinsufficient evidence to prove that LAA exclusion has a[2]benefit in terms of stroke reduction or mortality .PVIThe PVI approach was developed following the dis covery of the pulmonary veins being a key area ofectopic depolarisation, resulting in atrial ectopic beatsand ultimately leading to AF. The PVI approach has beenused in a number of trials and was shown to producegood results in paroxysmal AF.[9]When first performed by Haïssaguerre et al 62%of patients were free from AF in a median follow up of7 mo. In studies that followed, empirical isolation of thepulmonary veins became the most common approachas it was observed that the ectopic foci contributing toAF were often variable.[9]In the study by Haïssaguerre et al , 94% of theectopic foci were found in the pulmonary veins. Thus,one would expect that by ablating those foci freedomfrom AF would be close to 90%. However, this has notbeen the case in studies looking at long term (5 year)freedom from AF using PVI, with the success rate beingas low as 30%-50% and the recurrence rate up to[20,21]70%.The reduced effectiveness of PVI can be attributed toincomplete transmural lesions and pulmonary vein recon nection. Another reason for the low success rates is thefact that the pulmonary veins are not the only triggersof AF. Exclusively using PVI may not be sufficientin patients with persistent and long-standing AF, asdemonstrated by studies where ablation of additional[22-24]areas improved the outcomes. However, due tolarge inter-study variation in ablation methodology it isdifficult to assess the effectiveness of PVI alone.ABLATION USING ENERGY SOURCESVarious energy sources have emerged over the lastdecade striving to replace the traditional “cut and sew”technique by replicating the transmural lesions whilst[31]using a less invasive approach . Nevertheless, the vitalpre-requisite for successful AF ablation, as demonstratedby the CM-III lesion set, is that the lesions need to becompletely transmural and contiguous bilaterally. Inaddition, it is fundamental that the lesions are placed[10,12,18]in the correct pattern. Therefore, an importantcaveat when looking at new ablation techniques is theability to achieve complete transmurality of lesions.The ablative energy modalities available for surgicaltreatment of AF are compared in Table 2.Radiofrequency ablationExclusion of LAARadiofrequency ablation (RFA) works by conducting analternating electrical current through the myocardium.The energy from this electrical current gets dissipatedthrough the myocardial tissue as heat, causing coagu lative necrosis and resulting in an area of non-conduc ting myocardium. Complications of RFA include injuryto collateral structures such as the pulmonary veins,[14,25]oesophagus and coronary arteries.The LAA has been associated with occurrence of strokein patients with AF. Studies have demonstrated thataround 90% of the thrombi are found in the LAA,making it the primary source of emboli. This has led tothe conclusion that successful closure of the LAA would[25,26]reduce the risk of such thromboembolic events.Several studies have investigated the link between LAAexclusion and reduction in stroke in patients with AF.[27]Healey et al(2005) performed an RCT of 77patients undergoing CABG where 52 of them underwentLAA occlusion. However, occlusion was successful in just66% of the patients. One patient had an intraoperativeWJC www.wjgnet.comUnipolar RFAThe effectiveness of unipolar RFA during concomitantcardiac surgery has been investigated by severalstudies.44January 26, 2016 Volume 8 Issue 1

Kyprianou K et al . Surgical management of atrial fibrillationTable 2 Comparing and contrasting the various available ablation modalitieAblationmodalityMode of ent limitationsControlled thermal damage andlesions caused by electrical currentLess operating timeReduced technical difficultyVariableCryoablation Targeted scarring by cooling tissueusing high-pressure argon andheliumInitial cellular destruction followedby fibrosis and full thicknessdisruptionMicrowaveProduction of lesions by thermalinjuryVisual confirmation oftransmuralityLess damage to surroundingtissues and vascularityLess endocardial thrombusElectrical isolation of atriaMinimal collateral damageMinimal scar formationLower risk of VTEIntercavity thrombusPulmonary vein stenosisOesophageal and coronaryartery injuryCoronary artery and phrenicnerve injuryAtrioesophageal fistulaConfirmation oftransmuralityVariation betweeninstrumentsVariable success rateCoronary artery damagepotentialVariableHIFUCreation of localised hyperthermiclesions using a focused beam ofultrasound energyFast epicardial lesionsFuture potential advantagevisualisation of thickness byultrasound and tailor madelesionsAtrioesophageal fistulaPericardial effusionPhrenic nerve injuryYesendocardialonlyLaserUse of high energy optical beams tocreate thermal lesionsWell demarcated lesionsNon-arrythmogenicRapid lesionsCrater formationPerforationTissue lossPoor visibility of scarYesRFAYesLess effectivecompared to othermodalitiesLimited evidenceHigh rate ofcomplicationsLimited evidencecurrently notrecommendedoutside trialsLimited evidencecurrently notrecommendedoutside trialsRAF: Radiofrequency ablation; HIUF: High intensity focused ultrasound.[32]Johansson et al (2008) looked at patients under going CABG in combination with unipolar RFA. Patientswere followed up for 32 11 mo (with intermediatefollow up at 3 and 6 mo) looking for sinus rhythm. Inthe RFA group 62% of patients were in sinus rhythmcompared to 33% in the non-RFA group. Patients whowere in paroxysmal or persistent AF were more likely toremain in sinus rhythm than patients with permanentAF. The presence of sinus rhythm at 3 mo was foundto be a high predictor of the patient remaining in sinusrhythm at further follow up.[33]Khargi et al (2005) looked at a cohort of patientswith permanent AF undergoing open-heart surgery(CABG, aortic and mitral surgery) together with unipolarRFA. Sinus rhythm was observed in 79% of patientsundergoing CABG/aortic surgery and 71% of mitralsurgery patients. Notably, adding RFA did not increasemortality compared to cardiac surgery alone.[34]Bukerma et al (2008) looked at patients fulfilling thecriteria for permanent AF who underwent concomitantcardiac surgery and unipolar RFA. Contrasting the highsuccess rates seen at the aforementioned studies, just52% of patients maintained sinus rhythm at 5-yearfollow up.All of the above studies used 24 h outpatient holterECG monitoring to detect the presence of sinus rhythm.An important pitfall is that asymptomatic AF can beeasily missed, as the monitoring is not continuousduring the follow up period. This needs to be taken into[2]account when designing future studies .Unipolar RFA combined with concomitant cardiacsurgery is considered to be effective in restoring sinusWJC www.wjgnet.comrhythm. Higher degrees of success rates are seen inparoxysmal or persistent AF, young age and smaller[2]LAD .Bipolar RFAThe effectiveness of bipolar RFA during concomitantsurgery has also been explored.[35]A meta-analysis conducted by Chiappini et al(2004) looked at 6 non-randomised studies of patientswith AF undergoing RFA as an adjunct to cardiacsurgery, where 76% freedom from AF was achieved at13.8 mo follow up with the overall survival rate being97.1%.[36]Similarly, von Oppel et al(2009) looked atpatients with persistent AF undergoing concomitantcardiac surgery and bipolar RFA compared to cardiacsurgery alone. Seventy-five percent of patients in theRFA group were free of AF at a 1-year follow up withmore than 60% of patients having restoration of leftatrial contraction.A best evidence topic on the effectiveness of bipolarRFA during concomitant cardiac surgery conducted by[37]Basu et al(2012), revealed that bipolar RFA wasmore successful in restoring sinus rhythm for at least1 year when performed together with cardiac surgery.In addition, a high survival rate was observed and theprocedure required an average of 15 additional minutesof cross clamp time.Bipolar RFA used in conjunction with cardiac surgeryhas a higher success in restoration of sinus rhythmcompared to cardiac surgery alone. There is limitedevidence to conclude whether bipolar RFA is more45January 26, 2016 Volume 8 Issue 1

Kyprianou K et al . Surgical management of atrial fibrillationeffective than unipolar RFA. Further studies comparing[2]the two modalities are needed .used in minimally invasive techniques.[41]MacDonald et al (2011) conducted a best evidencetopic regarding the effectiveness of microwave ablationfor AF treatment during concomitant heart surgery.Eleven studies were reviewed with a large degreeof heterogeneity observed between the studies. Thesuccess rate ranged between 65%-87% over a variablefollow up period between 6-12 mo. The conclusion wasthat microwave ablation is not currently recommendeddue to limited evidence and unclear long-term successrates.[42]Lin et al (2010) compared microwave ablation tobipolar RFA. A RCT was conducted where patients wererandomised to a radiofrequency or a microwave ablationgroup. Patients were then followed up at 3, 6, 9 and12 mo and then annually. With a mean follow up of 24mo, freedom from AF in the radiofrequency group was88.7% compared to 71.2% in the microwave ablationgroup (P 0.0008). Thus bipolar radiofrequencyablation was demonstrated to be superior to microwaveablation.[43]Kim et al (2010) compared cryoablation to micro wave ablation in patients with mitral disease and AF.They demonstrated a 5-year freedom rate from AF of61.3% in the microwave group compared to 79.9% inthe cryoablation group. Additionally, microwave ablationwas associated with more frequent AF recurrence rates.Microwave ablation is currently considered to beless effective than other ablation modalities, based on[2]the limited evidence . Further studies are needed toinvestigate the effectiveness of microwave ablation as adefinite treatment of AF.CryoablationCryoablation works by cryothermal energy, generatedby the use of pressurised liquid nitrous oxide resultingin cooling of the surrounding tissue. Tissue injury occursby the creation of ice crystals within the cells disruptingthe cell function and electrical conductivity. Additionally,microvascular disruption ensues resulting in cell death.Complications of cryoablation include phrenic nerveinjury, atrioesophageal fistulas and coronary artery[14,24]injury. Several studies have proved the efficacy ofcryoablation in the treatment of AF.The PRAGUE 12 (2012) was a randomised multi centre trial that is considered a milestone trial for AF.It looked at 224 patients with AF undergoing valvereplacement or coronary surgery. The patients wererandomised in two groups with group A undergoingsurgical ablation and group B having no ablation. In theablation group, 96% had treatment with a cryoprobe.The procedure performed consisted of PVI, mitralannulus lesion, LAA lesion and a connecting lesion. At 1year follow up 60% of patients that underwent ablationwere in sinus rhythm compared to 36% in the untreatedgroup. At 1 year follow up no clinical benefits were seenin patients who underwent AF surgery; however thestudy is still ongoing and results for the 5-year follow up[38]are yet to be published .[39]Camm et al(2011) conducted a best evidencetopic looking at the effectiveness of cryoablationduring concomitant cardiac surgery. Nine studies werereviewed, including RCTs and retrospective studies.Cryoablation was found to be an acceptable surgicalintervention, achieving sinus rhythm in 60%-82% ofpatients at 12 mo follow up.[40]Blomström-Lundqvist et al(2007) conducted aRCT looking at patients undergoing concomitant AFsurgery and mitral valve repair. The results demon strated that undergoing cryoablation for AF treatmentsignificantly increased the return to sinus rhythm. 73.3%of patients in the cryoablation group were found to be insinus rhythm compared to 42.9% of those undergoingmitral valve surgery alone. However, it is worth notingthat patients in the cryoablation group had an increasedrate of complications. No significant increase in themortality or morbidity was seen in either group.Cryoablation during concomitant cardiac surgeryhas been proven to achieve good rates of sinus rhythmand it is more successful in patients with paroxysmal AFas opposed to permanent AF. Increased complicationrates from cryoablation were seen in just one study.Finally, a lack of 24 h monitoring meant that accurate[2,4]assessment of AF resolution was difficult .High intensity focused ultrasound ablationHigh intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) is a relativelynew ablative modality and works by creating a localisedthermal lesion using a focused beam of ultrasoundenergy. HIFU has been proven to create permanenttransmural lesions when applied epicardially. It hasthe advantage that CPB is not needed and can beperformed on the beating heart. HIFU can also bedelivered via a balloon catheter in order to facilitate[44]circum ferencial ablation of pulmonary veins .[45]Neven et al (2011) performed PVI using HIFU andsubsequently followed up the patients for 2 years. Anoesophageal temperature-guided safety algorithm wasused in an attempt to minimise the complications. At 2year follow up the success rate from the procedure wascomparable to that of radiofrequency ablation. However,severe complications were not prevented despite theuse of a safety algorithm. Complications included atrioe so phageal fistula, pericardial effusion and phrenic nervepalsy. They concluded that HIFU did not meet the safetystandards required for AF treatment, mainly becausephrenic nerve palsy and atrioesophageal fistula werestill common severe complications. The clinical use ofHIFU has currently been halted.[46]Davies et al(2013) followed up 110 patientsundergoing HIFU ablation for AF treatment. At a 2-yearMicrowave ablationMicrowave ablation works by producing a well-demar cated lesion through thermal injury. Its main advantageis that it produces good epicardial lesions and can beWJC www.wjgnet.com46January 26, 2016 Volume 8 Issue 1

Kyprianou K et al . Surgical management of atrial fibrillationfollow up 49% of patients remained in sinus rhythm.The percentage of patients in sinus rhythm was givenfor each of the pre-operative AF types: 81% forparoxysmal AF, 56% for persistent AF and 18% for longstanding AF. The conclusion was that HIFU is safe andeffective for use in paroxysmal AF, however alternativeablation strategies should be considered for persistentand long standing AF.[47][48]Klinkenberg et al(2009) and Schmidt et al(2009) have also demonstrated that despite relativelyhigh percentages of freedom from AF there is a highcomplication rate when using HIFU ablation. They haveconcluded that further research is needed to assessoptimal ablation techniques.HIFU ablation is currently not recommended outsidetrials due to the high rates of complications reportedand its success rates being inferior to other ablative[2]modalities . Further studies are looking at t

specific cardiac operations. This will help in identifying the combination of ablative modality and cardiac surgery yielding the best results. Tables 3-9 summarise the studies discussed in the sections above, looking at each modality available for surgical AF ablation. POST-OPERATIVE ANTICOAGULATION AND FOLLOW UP Post-operative anticoagulation