Transcription

1042-2587 2012 Baylor UniversityE T&PEffectuation, Causation,and Bricolage: ABehavioral Comparisonof Emerging Theoriesin EntrepreneurshipResearchGreg FisherThis study provides a critical examination of how different theoretical perspectives inentrepreneurship research translate into individual behavior, and whether such behavior isevident in the creation and development of new ventures. Using an alternative templatesresearch methodology, the behaviors underlying the theories of effectuation, causation, andbricolage are evaluated to see whether such behaviors are observable in case study datadescribing the early development of six new ventures. The analysis highlights behavioralsimilarities and differences between the various theoretical perspectives in entrepreneurship research, providing insight into how these perspectives contrast and complement oneanother, and how they could be integrated in future research.IntroductionAs interest in entrepreneurship as a domain of research has intensified, so a numberof new theoretical perspectives have emerged to explain the actions and logic that underlieentrepreneurial behavior. These approaches, which contrast with the more traditionalmodel of entrepreneurial behavior, have broadly been referred to as the “emerging theoretical perspectives” for entrepreneurship research (Eisenhardt, Kotha, Meyer, & Rajagopalan, 2010). The traditional model of entrepreneurship draws largely on economicthinking to describe how an individual or firm takes entrepreneurial action by searchingfor areas where the demand for a product/service exceeds supply (Casson, 1982; Khilstrom & Laffont, 1979) to discover an entrepreneurial opportunity, and evaluate whetherit is worth exploiting (Shane & Venkataraman, 2000; Venkataraman, 1997). After decidingto exploit an opportunity, an entrepreneur takes action by seeking resources to establish anentity that will develop and deliver a product or service to exploit the identified opportunity, and in so doing, create returns from the venture. Alternative theoretical perspectivesfor describing entrepreneurial action—such as effectuation (Sarasvathy, 2001) and entrepreneurial bricolage (Baker & Nelson, 2005)—suggest that under certain conditions,Please send correspondence to: Greg Fisher, tel.: 206 909 3146; e-mail: fisherg@indiana.edu.September, 2012DOI: 10.1111/j.1540-6520.2012.00537.xetap 5371019.10511019

entrepreneurs take a different route to identifying and exploiting opportunities. Accordingto the emerging theoretical perspectives of entrepreneurship, entrepreneurs (1) focusprimarily on the resources they have on hand and ignore market needs in uncovering anopportunity (Baker & Nelson; Sarasvathy); (2) ignore long-run returns and focus primarily on what they are willing to lose in making decisions about whether to pursue anopportunity (Sarasvathy); (3) refuse to enact the resource limitations dictated by theenvironment (Baker & Nelson); and (4) eschew long-range goals and plans (Sarasvathy).Prominent emerging theoretical perspectives in entrepreneurship research appear to havemuch in common with each other, yet they have largely developed and evolved independently of one another.1 The first aim of this research is to compare and contrast theprominent emerging theoretical approaches for entrepreneurship research. To effectivelycompare and contrast these approaches, one needs to assess them with a common unit ofanalysis. Because entrepreneurship is about action (McMullen & Shepherd, 2006), andbecause action in entrepreneurship is often observed as an individual behavior (Bird &Schjoedt, 2009), entrepreneurial behavior is a useful unit for this analysis. Entrepreneurial behaviors are the “concrete enactment of individual or team tasks required to start andgrow a new organization” (Bird & Schjoedt, p. 328) that manifest as “discrete units ofindividual activity that can be observed by an audience” (Bird & Schjoedt, p. 335). Thesecond aim of this research is to link the critical elements of the emerging theoreticalapproaches for entrepreneurship research to the individual behavior of entrepreneurs, andthen to see if such behaviors are observable in people starting new ventures.To achieve these aims, I translate the major elements in emerging entrepreneurshiptheories into behaviors and then adopt an alternative templates research strategy(Langley, 1999) to examine the individual behaviors pertaining to the emergence andgrowth of six new consumer Internet ventures founded between 2000 and 2003. Thealternate templates research approach, which was popularized by Allison (1971) in hisstudy of decision making at the time of the Cuban Missile Crisis, provides for “severalalternative interpretations of the same events based on different but internally coherentsets of a priori theoretical premises” (Langley, p. 698). This allows one to “assess theextent to which each theoretical template contributes to a satisfactory explanation”(Langley, p. 698), and in so doing, provides insight into how various theoretical perspectives are related to one another.This paper proceeds as follows: In the first section, the theory and literature relatingto each of the theoretical approaches addressed is briefly reviewed. The processes encapsulated within each theory are translated into entrepreneurial behaviors—“discrete unitsof individual activity that can be observed by an audience” (Bird & Schjoedt, 2009,p. 335). Thereafter, the data and methods used in this research are described, and thefindings that emerged from the analysis of six new ventures are reported. The final sectionoutlines the conclusions and implications of this research.Theory ReviewSelection of Theoretical PerspectivesOver the past decade, a number of different theoretical perspectives have emerged todescribe the logic and behavior underlying the entrepreneurial process, e.g., effectuation1. The foundational articles for each perspective (Baker & Nelson, 2005; Sarasvathy, 2001) do not cite eachother. A review of more recent literature under each of these theoretical perspectives suggests there is limitedcross-citation between research on effectuation and entrepreneurial bricolage.1020ENTREPRENEURSHIP THEORY and PRACTICE

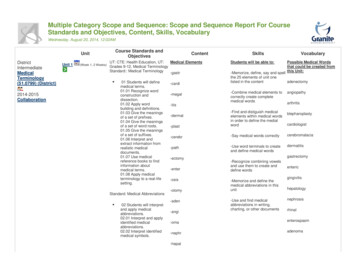

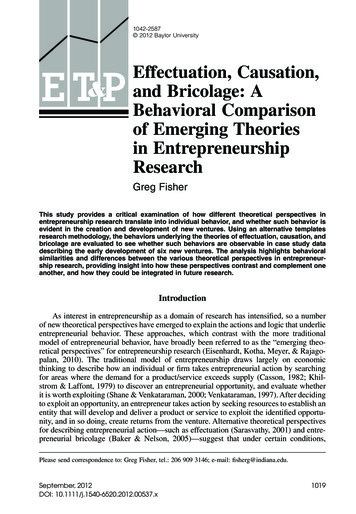

(Sarasvathy, 2001), entrepreneurial bricolage (Baker & Nelson, 2005), the creation perspective (Alvarez & Barney, 2007), and user entrepreneurship (Shah & Tripsas, 2007).These new theoretical perspectives have largely sought to describe the differencesbetween the traditional approach to entrepreneurship (called the “causal approach” bySarasvathy (2001), the “discovery approach” by Alvarez and Barney, and the “classicapproach” by Shah and Tripsas) and an alternative approach. While it would be valuableto compare and contrast all these theoretical perspectives with the traditional perspective,in the interest of parsimony, the focus of this research is on the traditional approach andtwo prominent emerging theories. Using the criteria of generality and impact, I focus oneffectuation and bricolage as the two emerging theoretical perspectives to be comparedwith a traditional approach to entrepreneurship research. Both these theoretical perspectives offer general explanations of entrepreneurship,2 and the foundational papers foreffectuation (Sarasvathy, 2001) and entrepreneurial bricolage (Baker & Nelson) are morewidely cited than the papers pertaining to the other alternative theoretical perspectives.3Sarasvathy (2001) describes the traditional approach to entrepreneurship as a “causalapproach”; therefore, I adopt the concept of causation in this research to capture andoutline the traditional theoretical perspective. The three theoretical perspectives that areexamined in this research are causation, effectuation, and entrepreneurial bricolage.Framework for Reviewing the Theoretical PerspectivesWhetten (1989) proposes that the journalistic questions of who, what, where, when,why, and how are useful for describing the building blocks of theory. In this section, thesejournalistic questions are applied as an organizing framework to dissect the elements ofeach of the relevant entrepreneurship theories. Within this framework, the what elementaddresses the following question: What factors (variables, constructs, concepts) should beconsidered as part of the explanation of the social or individual phenomena of interest?The how element concerns how this set of factors is related. The why element thenaddresses the “underlying psychological, economic, or social dynamics that justify theselection of factors and the proposed causal relationships” (Whetten, p. 491). Thus, whatand how provide description, while why provides explanation. Finally, the who, where,and when elements act as conditions that place limitations on the propositions generatedfrom a theoretical model: “These temporal and contextual factors set the boundaries ofgeneralizability, and as such constitute the range of the theory” (Whetten, p. 492). Table 1provides an overview of the causal, effectual, and bricolage approaches to entrepreneurship using Whetten’s questions—what, how, why and who, where, when—as an organizing framework. Each of these approaches is further expanded on in the next section usingthe same framework to guide the discussion.CausationCausation is the term used by Sarasvathy (2001, 2008) to describe a traditionalperspective on entrepreneurship. Under a causation model, an individual entrepreneur2. I am grateful to the reviewers for pointing out that effectuation and bricolage are both “more generalexplanations of entrepreneurship.”3. At the time of conducting this research, Sarasvathy (2001) had been cited 778 times according to GoogleScholar; Baker and Nelson (2005) had been cited 385 times; Shah and Tripsas (2007) had been cited 72 times;and Alvarez and Barney (2007) had been cited 236 times.September, 20121021

Table 1Entrepreneurship Theories1. Causation4What factors are part ofthe explanation?Causation: Outcome is given Select between means toachieve that outcome by:1. Starting with ends2. Analyzing expected return3. Doing competitive analysis4. Controlling the futureHow are the factorsidentified related tooutcomes of interest?Causation processes identifyingand exploiting opportunities inexisting markets with lowerlevels of uncertainty. Later entrants into an industry causation processesWhy can we expect theproposed relationshipsto exist?Decision theory:Decision makers dealing withmeasurable or predictablefuture will do systematicinformation gathering andanalysis within certain bounds(Simon, 1959). Static, linear environment. Predictable aspects of anuncertain future arediscernible and measurable. Entrepreneurial opportunitiesare objective and identifiablea priori.Who, Where, When?The assumptions andlimitations underlyingthe theory (boundaryconditions)2. Effectuation5Effectuation: Set of means are given Select between possibleeffects that can be createdwith those means by:1. Starting with means2. Applying the affordable lossprinciple3. Establishing and leveragingstrategic relationships4. Leveraging contingenciesEffectuation processes identifying and exploitingopportunities in new marketswith high levels of uncertainty. Successful early entrants intoa new industry effectuationprocesses Effectual firms fail earlyand cheapDecision theory:Decision makers dealing withunpredictable phenomena willgather information throughexperimental and iterativelearning techniques aimed atdiscovering the future. Dynamic, nonlinear, andecological environments. Future is unknowable and notmeasurable. Entrepreneurial opportunitiesare subjective, sociallyconstructed, and createdthrough a process ofenactment.3. Entrepreneurialbricolage6Entrepreneurial bricolage: Make do with what is at hand Create something fromnothing by:1. Making do2. Combining resources for newpurposes3. Using resources at handEntrepreneurs in penuriousenvironment option to seekresources; ignore theopportunity to engage inbricolage. Bricolage in multiple domains reinforcingpatterns stalled growth. Bricolage in selective domains efficient routines growth.Social construction:Resource environments aresocially constructed, whichallows for specific social andorganization mechanisms tofacilitate the creation ofsomething from nothing. Resource environments aresocially constructed. Entrepreneurs confrontsituations of significantresource constraint. Entrepreneurs have access tosome resources on hand thatcan be used to “make do.”Phenomena of interest: The process employed by entrepreneurs in identifying and exploiting an opportunity for a newproduct or service.decides on a predetermined goal and then selects between means to achieve that goal(Sarasvathy, 2001). Entrepreneurship is reflected as “a linear process in which entrepreneurvolition leads to gestational and planning activities” (Baker, Miner, & Eesley,2003, p. 256), and involves “. . . the process of discovery, evaluation and exploitation of4. Sarasvathy (2001, 2008).5. Sarasvathy (2001, 2008).6. Baker and Nelson (2005).1022ENTREPRENEURSHIP THEORY and PRACTICE

opportunities” (Shane & Venkataraman, 2000, p. 218). Central to this approach areconcepts of intentionality (Katz & Gartner, 1988), opportunity identification and evaluation(Shane & Venkataraman), planning (Delmar & Shane, 2003), resource acquisition (Katz &Gartner), and the deliberate exploitation of opportunities (Shane & Venkataraman).What Factors Form Part of the Explanation? The factors that form part of the explanation of the entrepreneurial process include the identification and evaluation of objectiveopportunities (Shane & Venkataraman, 2000), the establishment of goals to exploit identified opportunities (Sarasvathy, 2001), and the analysis of alternative means to fulfillgoals while accounting for environmental conditions that constrain the possible means(Sarasvathy). Criteria for choosing between means usually involve maximizing

(Simon, 1959). Decision makers dealing with unpredictable phenomena will gather information through experimental and iterative learning techniques aimed at discovering the future. Resource environments are socially constructed, which allows for specific social and organization mechanisms to facilitate the creation of something from nothing. Who, Where, When? The assumptions and limitations un