Transcription

DOCUMENT RESUMEUD 029 740ED 369 848AUTHORTITLEINSTITUTIONSPONS AGENCYPUB DATENOTEPUB TYPEEDRS PRICEDESCRIPTORSIDENTIFIERSOlinger, Betty; Partee, TeresaEvening the Odds: Taking Action for Kentucky'sAfrican American Children and Their Families.Kentucky Kids Count Consortium.; Kentucky YouthAdvocates, Inc., Louisville.Annie E. Casey Foundation, Greenwich, CT.17 Jan 9477p.ReportsStatistical Data (110)Descriptive (141)MF01/PC04 Plus Postage.*Blacks; Census Figures; Child Health; CommunityAction; Comparative Analysis; *Disadvantaged Youth;*Economically Disadvantaged; Educational Trends;Elementary Secondary Education; Employment; FamilyIncome; Family Structure; Foster Care; Housing;Infant Mortality; *Minority Group Children;Population Trends; Statistical Data; Tables (Data);Trend Analysis*African Americans; *KentuckyABSTRACTThe 1989 census data f-- the state of Kentucky.Lre more than twice as likelyreveals that African American childrto be poor as White children, three times more likely to grow up in asingle parent family than White children, and twice as likely asWhite children to live in a home that is rented as opposed to owned.The data also show that the African Americans' per capita income isonly 65 percent that of Whites. This report, focusing on Kentucky'sAfrican American children and their families, analyzes trend data andpresents statistics in five areas of concern: health, out-of-homeplacements, education, employment, and housing. It suggests actionsto improve the status of African American children and families atthe family, community, and governmental levels. Data sheets are alsoprovided covering 1990 census data, 1992 vital statistics, andindicator trend data for each county within the state possessing themost African American households as well as in area developmentdistricts. **************,:*************Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made*from the original *******************************

U S DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION4.O'fice of Educationai Research ano linproementEDATIONAL RESOURCES INFORMATIONCENTER tERIC1This document has been reproduced asreceived from me person or organizationoriginating it0 Minor changes have been made toimprove reproduction qualityPoints of view or opinions slated in thisdocument do not necessarily representofficial OERI position or policy"PERMISSION TO REPRODULE THISMATERIAL HAS BEE GRANTED BYD.S mil .)2(ActuaTO THE EDUCATIONAL RESOURCESINFORMATION CENTER (ERIC)7:41111tkg,

EVENING THE ODDS:Taking Action for Kentucky's African American Children and Their FamiliesWritten byTeresa Partee, MSSWResearch AssociateKentucky Youth Advocates, Inc.Betty Olinger, Ed.D., R.N.Associate Professor of NursingBerea CollegeEditorMargaret Nunnelley, MSSWPolicy AnalystKentucky Youth Advocates, Inc.a joint project ofThe Kentucky KIDS COUNT ConsortiumandKentucky Youth Advocates, Inc.2034 Frankfort AvenueLouisville, Kentucky 40206(502)895-8167January 17, 1994This report was juinded by a grant from The Annie E. Casey Foundation in Greenwich, Connecticut.Recommendations and opinions are the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Foundation.3

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTSTwo reports served as models for this document. The first. "Facing the Facts," was prepared by the Children's DefenseFund Ohio. The second. "Progress and Peril: Black Children in America," is from The Black Community Crusadefor Children ( BCCC) coordinated by the Children's Defense Fund. Washington. D.C. (For more information aboutthese groups call 1-300-ASK-BCCC.)Under the Kentucky KIDS COUNT contract. the Center for Urban and Economic Research at the University ofLouisville provided much of the data which we included in this report.We appreciate the invaluable assistance we received in preparing this report. In particular, we would like to thankTeresa Partee, a graduate student at the Kent School of Social Work. University of Louisville. Teresa was responsiblefor collecting most of the data and developing many of the initial ideas incorporated in this document.Finally, we would like to acknowledge the African American persons who agreed to be interviewed for this documentand those who read the report prior to its release. The information we gained from these persons was of greatimportance to us in portraying the circumstances of Kentucky's African American population.Funding for this report and other activities of the Kentucky KIDS COUNT Consortium is provided through a grantfrom The Annie E. Casey Foundation in Greenwich, Connecticut. The grant to the Kentucky Consortium is partof the Casey Foundation's national KIDS COUNT effort to publicize the needs of children, influence budget andprogram decisions, and monitor state and local pert, -mance for children.Evening the Odds4

Dear Concerned Citizen:As I helped prepare this report I found myself wearing several hats, each retlectine a different aspect of my life. Asan educator and parent. I am aware of the many challenges, obstacles, and pressures that the youna people ofKentucky face daily. As an African American. I am also aware of the disparities of status between African Americanand white families. As an Associate Professor of Nursing at Berea College, I see the bright faces of cage- AfricanAmerican students, many of whom have endured tough times in order to secure greater opportunities in life. As theChildren's Defense Fund documented. African American children and families are currently facing one of theworst crises since slavery. In Kentucky. 47 percent of our African American children live in poverty.The information in this report illustrates the critical dilemmas of many African American families in Kentucky. Wehave taken special pains to highlight some of the successful ways these problems can be ameliorated. We hope ourrecommendations will provide a starting point in combatine some of these longstanding dilemmas.I write this letter to ask you to begin taking action at one or more of three levels. First, you can help African Americanchildren and their families through your donations or by volunteering to participate in a mentoring program operatedby one of the many community organizations that focus on helping African American children and families. Secondly,perhaps you will see unmet needs in this report which will prompt you to develop a new proeram to empower younaAfrican Americans and their families. And finally, you may become an advocate encouraging better funding for thegovernment programs that help African American children and families. We can no longer accept the complacencyadopted by so many members of our communities or assume that these problems will be taken care of by someoneelse. The time to take action is now.Sincerely.eeBetty H. Olinger, Ed.D., R.N.Evening the Odds5

TABLE OF CONTENTSINTRODUCTION14MATERNAL AND CHILD HEALTHInfant Mortality Rate Improves but African AmericansAre Still BehindAfrican Americans Receive Less Early Prenatal Care Than WhitesTeen Birth Rate Rises for African Americans4578OUT-OF-HOME PLACEMENTAfrican American Children Are Over-Represented in Foster Careand Other Placements89EDUCATION9The Dropout Rate: No Real Difference by RaceTracking and Ability GroupingCollege Enrollment and GraduationThe Shortage of African American Teachers101012EMPLOYMENT AND INCOMEAfrican American Unemployment: The Erosion of DignityTeenne Unemployment RateContinuing Disparity in Income12131414HOUSINGHome Ownership Remains a Dream for Many African AmericansAfrican Americans and Loan RejectionsEvening the Odds61415

OUR VISION FOR KENTUCKY'S CHILDREN16TAKING ACTION17Ten Thin 2s Government Can Do To HelpAfrican American Children and Their FamiliesTen Things Communities Can Do To HelpAfrican American Children and Their FamiliesTen Things Families Can Do To Help Their Children171920HOW TO RECEIVE MORE SPECIFIC INFORMATION ONAFRICAN AMERICAN CHILDREN IN YOUR ARE22By the Eleven Counties with the Most African American HouseholdsBy Area Development DistrictABOUT THE AUTHORS AND THE EDITOR2222237Kentucky Youth Advocates and Kentucky KIDS COUNT

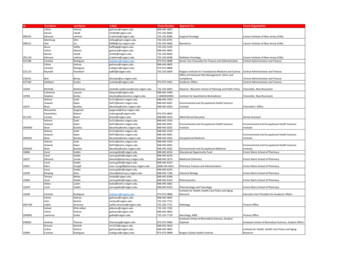

INTRODUCTIONThe Kentucky KIDS COUNT Consortium has spent the past three years gathering,"The dismal pictureanalyzing, and reporting data concerning all children in Kentucky. This report, however,focuses specifically on Kentucky's African American children and their families.that is painted in thisCensus data gathered in 1989 indicate that 7 percent of Kentucky's total population isAfrican American. The same source reports that 9 percent of children in Kentucky areAfrican American. While African Americans are dispersed throughout the state, 78percent of Kentucky's African American children live in only 11 of the state's 120report reflects a longcounties. In 29 Kentucky counties there are no, or virtually no African American children.which has existed instanding problemThe map below indicates what percent of the population in each Kentucky county isthe African AmericanAfrican American.community for years.Percentage of African Americansin Kentucky CountiesIt is time that we stopgathering data and0.0% to 1.9%proceed with a2.0% to 4.9%solution to address the5.0% to 9,9%10.0% to 24.6%problem."Darryl T. OwensJefferson CountyCommissioner1Evening the Odds8

By far, the two most compelling -- and most often cited -- statistics on African Americansin the state are that 47 percent of Kentucky's African American children are poor,and 59 percent of African American families with children are headed by singleparents. The odds for African American children in Kentucky are not good. Currentlyin Kentucky:African American children are more than twice as likely to be poor as whitechildren;African American children are almost three times more likely to grow up in asingle parent family than white children;African American children are twice as likely as white children to live in a homethat is rented as opposed to owned; andAfrican Americans' per capita income is only 65 percent that of whites.This report analyzes data concerning African Ariericans to determine upward anddownward trends. The document presents compelling and in some cases alarmingstatistics in five areas of concern: health, out-of-home placements, education, employment, and housing. It suggests actions to improve the status of African American childrenand families in Kentucky at three levels: family, community, and government.Throughout this book, we tell stories to high' -ht personal experiences, opinions, andcurrent promising programs. This report prc .es such alarming data that we cannotimagine anyone being complacent about the circumstances under which African American children are living. Nor can these conditions be justified. This report was designedto heighten awareness of the situation and initiate a problem solving process within ourcommunities and the state as a whole.92Kentucky Youth Advocates and Kentucky KIDS COUNT

WHAT IF AFRICAN AMERICAN CHILDREN FACED THESAME ODDS'ASWHITECcHILDREN?,,0,,,,Y,0,-,. ,v, :.4 :'' 4'''' ,.''.,:":' ': :,;;',W,',/::::',,t*',. ,-,P,';:,,, ' .'': 'If African American.faibillos.indilheir children faced i ., 4tste odds as white,.6".:.:,:4e.:1/1,?,.,;.;'.11.:.,o.families and children; 41. jetintuckk,'paoh 'rcar:,- ,.,;,-,:,,.:,-;,-,:,.,.:,s, : ,,,:,',1,,,;:,:',,,:-,;.:.':;.,.:d, ::, .-;,,:',.,-4.?:.:;.,.,.,,:.,,.:.'':.,,,-.,,,;,,.- ';' ,,:,;;- ,',' ,:',-,,,:,:',:',:,,.,,,,.;:,,,,.:.,.,,,.19,362 fewer African- Aihericari'.edren would hve :11!.:0.verty;,1:,:', :,:::''.''''',1ora-theit firSt, liirthd ay:43 fewet African American infants ,wou,,:. '44):',0 .1:." t:;' 'WM.;7,s,',.,,,; ;:741,. 41.?".''''r.:-,,'.:V",';'%I.;44',. V,:.,,.7,7q:, ,:!:'');',.:,',Irti; V'.:;''',"; '''.1.'''';.t.4-"!:''i:'.":''' 1' ;;'." '', '.772 feWer.,.',.'1,,,;!, 90--Atnericau''',.' .i'-,!f/, ',Eli tii mcithep who did,tes.,w0yld be11not:Te0i,e.:*,,,,, Wif ,444, ,,,:;,;;4r;;#1.t;1!1:;: ''''':'. ::,',.17,7g.',:i,IP,V' ',.0.;.;,.,:. ;,:.4,,,i1A.,'5'.-.'2,036.f W,.k.,.,tilt*, 4 les would be born to unmarried;.e.;.;,;i.,,,,,,, -.,u.s.,.,- -4:,i,,,,,,,{.(;.:,,,.,eriOn babieq would be:horn to mothers under 18year"1115,851 osverheaci87.0tattM erican families with children would be,.4riCan: Americans would be unemployed;dreu. Would live in out-of-home(Concept adnpted from Piand Palk B.Community Cmsade fot Children. Kentucky data areCensus, the 1992 Vital Statistics report, and a 1993'Wren In America by the Blackonmformation taken from the 199Ciky Department for Social Services3Evening the Odds10BEST COPY AVAILABLE

MATERNAL AND CHILDHEALTHof early prenatal care provided to pregnantwomen. and (2) the care that babies reeeiveimmediately after birth and throughout theirfirst year of life. Research suggests thatwomen who receive early prenatal careINFANT MORTALITY RATEhave healthier babies, reducing the risk ofinfant mortality.IMPROVES BUT AFRICANAMERICANS ARE STILL BEHINDFigure I shows the infant mortality rates forAfrican Americans and whites from I 98 I to1992. The infant mortality rate for AfricanAmericans in 198 I was 17.9 per 1.000 liveAfrican American infants are almosttwice as likely to die in their first year oflife as are white infants. The infantmortality rate reflects the number ofbirths and in 1992, was 14.7. The infantbabies who die during their first year oflife per 1,000 live births. Many factorsare related to infant mortality rates. Twoof the most commonly cited are: (I) lackmortality rate !'or whites were 11.7 and 8.0per 1,000 live births for the years 198 I and1992 respectively.Figure 1: Infant !Mortality Rates by Race1981-1992African AmericanWhite25z 20-111C 10 -1I.0.i1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992Source: Center for Urban & Economic Research, Unisersity ol LowsvilleiKintucky Youth Advocates and Kentucky KIDS COUNT

Low birthweight has a major influence oninfant mort.ality. African American womenare more likely than white women to givebirth to babies weighing less than 5.5pounds. Recent national studies seem toshow that this tendency among AfricanAmerican women to have smaller babies isnot totally explained by either income oreducation levels.AFRICAN AMERICANS RECEIVELESS EARLY PRENATAL CARETHAN WHITESEarly prenatal care (provided in the firsttrimester of pregnancy) is essential forhealthy babies. Studies have shown thatearly prenatal care reduces the risk oflow birthweight babies, premature labor, and infant mortality.RESOURCE MOTHERS: A PROGRAM FORPREGNANT AND PARENTING TEENS"Essentially, ourchildren need to bestrengthened withth theOike program that is helping to alleviate the problems of infant mortality, low birthweight,and other health and social problems related to adolescent pregnancy is the Resource Motherc7ntext of programsProgram provided by local health departments. By January 1994 the program will beavailable in 60 of Kentucky's 120 counties. Resource Mothers' employees visit pregnantthat work to strengthenand parenting teens at home and assist with the non-medical dimensions of pregnancy andchild rearing. These resource mothers are experienced professionals or paraprofessionals.Efforts are made to match clients and Resource Mothers' employees by race. The rez-aurcemothers encourage pregnant women to attend prenatal care appointments and provide childrearing advice for the child's first two years of life.the whole family."Dr. Roz HarrisProfessor of SociologyUniversity of KentuckyThe following is an excerpt from a letter a Resource Mothers' client wrote to the LexingtonFayette County Health Department. The people served by this Fayette County program are71 percent African American."1 would like to thank the Health Department for their employees and for the dedication fromKathy Eherhart, my nurse, for coming to my house and talking with me about prenatal care.A,:id if it wasn' t for Kathy Eberhart, I would not have had my healthy baby boy. Becausehe told my Mom to call U.K. [hospital] because it wasn't normal for me not feeling the babykick. So U.K. had admitted me in and the docto.s told my Mom and Dad if I had waitedtwo hours later, the baby wouldn't be alive today. I want to thank God for bringing KathyEberhart to my house that day."1Evening the Odds512

While the percentages of both AfricanAmericans and whites receiving earlyprenatal care have increased in the lastten years, African American women arestill less likely to begin care in the firsttrimester of pre2nancy. Over threefourths of prettnant whites (79.8 per-While prenatal care is more available nowthan ten years ago. some subtle barriers,including education about pregnancy, access to clinics, and personal shame. stillstand in the way of receiving care during1992, compared to less than two-thirdspregnancy. Lack of transportation preventssome low income Kentuckians from securing health services. According to Kentucky's1990 census information, in housing unitsof pregnant African Americans (64.5occupied by white persons, 10.1 percentpercent). As Figure 2 suggests, this gaphave no vehicle. By comparison, in housingunits occupied by African Americans. 31.2cent) received early prenatal care inbetween African American and whitepregnant women receiving early prenatal care has not reduced over the lastdecade in Kentucky.percent have no vehicle (more than threetimes as many as whites).Figure 2: Women Receiving Early Prenatal Careby Race in Kentucky1981 -1992African American-- 10 White8060 10.20 ;10 10119811982 1983 1984 1985 19861987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992Source: Center for Urimn & Economic Research. University of Louisville63Kentucky Youth Advocates and Kentucky KIDS COUNT

TEEN BIRTH RATE RISES FORFigure 3 shows, for the most recentAFRICAN AMERICANSyears, 1990-92, the African Americanteen birth rate for 12 to 17 year olds inTeens who give birth risk their health andthe health of their children. Health expertsKentucky is 47.5 births per 1,000 teens.The white teen birth rate is 19.2 for thesame three year period.warn that pregnancy complications are muchmore common for teen mothers than formothers age 20 and older. Additionally, thechances of having a low birthweight babyare increased for a teen mother. LowAs the graph below indicates, the Afri-can American teen birth rate hasrisen in the last decade while thebirthweight babies who survive have agreater chance of brain damage, slowwhite teen birth rate has fallen. Thewhite teen birth rate declined 21 per-growth, and nervous system problems.cent (from 24.2 to 19.2 per 1,000) fromThe teen birth rate (the number of births per1.000 teens) in Kentucky for African Americans is more than double that for whites. Asbirth rate increased 11 percent (fromthe 1980-82 period to the 1990-92period. The African American teen42.9 to 47.5 per 1,000) in the same timeperiod.Figure 3: Kentucky's Teen Birth Rates, Ages 12-17 by Race60E African AmericansE3 WhiteR 5047.5Base Years (80-82)Recent Years (90-92)Source: Center for Urban & Economic Research, University of LouisvilleEvening the Odds147

OUT-OF-HOMEPLACEMENTThe large number of African Americanchildren in out-of-home placements mayreflect the economic situation of many ofKentucky's African American families.AFRICAN AMERICAN CHILDRENAnother possible explanation for so manyAfrican American children in out-of-homecare may lie in the fact that many AfricanAmerican children come from single parentfamilies who are particularly subject to theARE OVER-REPRESENTED INFOSTER CARE AND OTHERPLACEMENTSAccording to the Kentucky Departmentof Social Services, as ofJuly 1993, 3,564stresses and strains that may lead to achild's removal. Some national expertschildren were in out-of-home care including foster homes, private child careagencies are quicker to remove Africanfacilities, group homes, and others.Twenty-four percent, or 851 of thesechildren are African American.Of the 524 Kentucky children awaitingadoption, 33 percent are African American. These figures are astounding, par-suggest that some courts and social serviceAmerican children than white children fromtheir homes in cases of abuse and neglect.African American parents -- who are morelikely to be poor are also more likely tohave inadequate legal representation incourt, resulting in their children being removed from their homes.ticularly since Kentucky's African Ameri-can population makes up only 9 percentof the total child population.ONE SOLUTION: THE BLACK ADOPTION PROGRAMThe Louisville Urban League operates the Black Adoption Program (BAP) in conjuction withKentucky One Church One Child. From 1989 to 1992, BAP noted a 100 percent increase inthe number of special needs children placed and a 170 percent increase in the number of AfricanAmerican families approved for adoption. BAP uses many strategies in their attempt todecrease the number of African American children awaiting adoption. For example, as a directresult of the roller skating party for 35 children and 20 familues held on August 29, 1992, onefamily met and adopted a sibling group of three youngsters. (a 14 month old girl, a two and ahalf year old boy, and a three and a half year old boy). In addition, two other children wereplaced and four adoptive or foster families pledged their support for new adoptive or fosterfamilies.87I 5(entucky Youth Advocates and Kentucky KIDS COUNT

EDUCKI IONpercent. Data on dropout rates col-DIFFERENCE BY RACElected by the Kentucky Department ofEducation are not kept by race, explaining why the most recent data availablewas from the 1990 census.The dropout rates for African American andTRACKING AND ABILITYTHE DROPOUT RATE: NO REALwhite students in Kentucky are not appreciably different. As the chart in Figure 4shows, according to 1990 U.S. Censusdata, the percentage of black teens, 16-19years old, who have not graduated fromhigh school and are not enrolled in school is13.6. The figure for white teens is 13.3Figure 4: School Dropouts inKentucky by RaceGROUPING"Students must heWhile there is little disparity betweenAfrican American and white dropoutrates, other trends in education for whichfewer hard statistics are available sug-taught that "smart" isgest some racial disparity. Natio. ial stud-are as sharp cis anygood. Black childiies show that African American students are more likely than whites to beplaced in special education classes andless likely than whites to be placed inchildren of any raceon earth."gifted and talented classes. For example,at one elementary school in JeffeisonCounty, African American students, whomade up nine percent of the total enroll-ment, accounted for 89 percent of allReverend DoctorWilliam Sununers II!President.KentuckyInterfaith. Comnzunitystudents in the lower track classes.African American students are also disproportionately more likely to be subjected to practices such as suspension,expulsion, and corporal punishment.Current government policies contributeto inequitable retention and treatmentof students by not mandating data col-Source: Center for Urban & Economic Research.University of Louisvillelection by race for monitoring purposes.While the Office of Civil Rights of theU.S. Department of Education randomly9Evening the Odds

LIFTING CHILDREN UP: FROM THEIR ABCsTO THEIR COLLEGE DEGREES"1Vhen I was a child.we had trucking ofThe Lincoln Foundation, located in Louisville, established The Educational OpportunityScholarship Fund. This scholarship program targets children (primarily minority) who areat "high risk" of not finishing high school or going on to college. The program begins fundingsorts but there was notas much classchildren in preschool, continues through four years of college and covers all educationalexpenses, except a minimal contribution by the family. Children sought by the program are"average" in terms of ability, neither "gifted" nor "slow." For more information on theEducational Opportunity Scholarship, call the Lincoln Foundation at 502-585-4733.conscienciousness asthere is now. If youwere smart, you weregrouped with Otheracademically talentedselects school districts throughout thenation to analyze treatment and placerment equity, this data should be col-only 3.7 percent of degrees awarded to in-lected every year in all Kentucky schoolWhile African American students enroll inhigher education institutions in proportionalnumbers, they are less likely to completetheir degree programs and therefore, lesslikely to reap the full rewards of a collegeeducation.districts so that educational practicesand placements can be monitored forequity.students. Your familyincome or where youlived was not part ofthe equation."Dr. Madeline Maupin HicksLouisville Activist and Dentiststate residents between July 1, 1991 and June30, 1992 went to African American students.COLLEGE ENROLLMENT ANDGRADUATIONTHE SHORTAGE OF AFRICANAccording to the Kentucky Councilon Higher Education, state-supportedAMERICAN TEACHERSuniversities had a total student enrollment of 93,142 in the fall of 1992. Ofthat number, 5,553 (or 6 percent) students were African American. This isnot particularly disturbing data sinceAfrican Americans make up 7 percentof Kentucky's college age population.A significant problem with the educationalsystem of Kentucky, affecting not only African American children, but also white chil-What is disturbing however, is that10dren, is the number of African Americanteachers. According to the University ofLouisville, Center for Urban and EconomicResearch and, as Figure 5 indicates, only 4percent (or 2,465) of teachers in KentuckyKentucky Youth Advocates and Kentucky KIDS COUNT17

schools in 1989 were African American.while 9 percent of the students were AfricanAmerican in the 1991-92 school year.It is important that African American students have role models andmentors in their schools. It is alsoimportant that white students beexposed to African Americans inFigure 5: Kentucky Students and Teachers by Racew Ira A owk.A,X : /\ [1'.C.-0reo.ckse-Source: Center for Urban & Economic Research, University of Louisville 800,000 FOR AFRICAN AMERICAN TEACHERSTo help increase the number of African American teachers in the state, Senator Gerald Nealhelped secure the passage of a bill that appropriated 400,000 for the fiscal year 1992-93 andanother S400,000 in 93-94 for the purpose of recruiting and training teachers of color.Summerbridge, located in Lexington, Kentucky, is one such recruiting pro2ram whichencourages students to stay in school and pursue a career in teaching. At Summerbridge,eleven 15 to 25 year-old students acting as teachers were responsible fot- teaching, counseling,and administering the four week program to other students and teachers.Evening the Odds1118

authority positions. Through AfricanAmerican teachers, white students wouldlearn more about other cultures and havethe opportunity to experience culturaldiversity in the classroom.a fOrmer teacher.I can see a day whenTEACHERS TO STUDENTSserving as role models and communicatorsAfrican AmericanKentucky. For example, in order forJefferson County' s African Americanteachers to match the percentage ofteachers in theadditional African American teachers.African American students in the county,the school system would have to hire 820The Jefferson County Public Schools andclassroom otherthe Louisville branch of the NAACPentered into an agreement to increase thethan ti coach."number of African American teachersand employees in the school system.Al LewisLouisville BusinessmanEMPLOYMENT ANDINCOMEAs University of Chicago scholar WilliamJulius Wilson points out, it is important forchildren to see adults leaving for work eachday to reinforce the work ethic. Theseadults serve as role models for children bydemonstrating that work is essential forsurvival and self-esteem. Unfortunately, inmany areas of Kentucky, the unemployment rate is so high that some children donot have the chance to see adults as responsible employed citizens.Figure 6 compares Kentucky unemployment data from the 1980 and 1990 U.S.Census. The University of Louisville'sCenter for Urban and Economic Researchreports that Kentucky's unemployment rateAFRICAN AMERICAN(the percent of people in the labor forceUNEMPLOYMENT: THE EROSION OFEmployment, above all other factors,who do not have a job and who are activelyseeking work) dropped from 8.5 percent in1980 to 7.4 percent in 1990. The percentages for both African Americans and whitesdetermines the fate of a family. Withoutadequate employment and the income itdropped. The African American rate decreased from 14.7 percent in 1980 to 13.7produces, African American families havelittle chance of securing housing, health,percent in 1990, and the white rate from 8.1DIGNITY12ance, and other benefits a family can afford.The ability to earn a living also brings withit a sense of self-esteem and security whichis important to both parents and their children.The lack of African American teachersof culture continues to be a problem inthere will be no mulefood, and clothing for their children. Notonly does adequate employment, providehousing, food, and clothing it also oftendetermines the level of health care, insur-'19percent to 6.9 percent.Kentucky Youth Advocates and Kentucky KIDS COUNT

Figure 6: KentuckyUnemployment Rate forPersons 16 and Over by Race16Mtn7 Afrionkneneins14,714-sential that this age group have employment opportunities. Some experts sug-gest that the probability of turning to13,712 -.to 35.5 percent. Not only did the rateincrease, but the gap widened betweenthe percentages of African Americanand white youth unemployed. It is es-111crime increases for individuals who areunemployed, as they seek other ways tomeet their financial needs. Additionally, without early job training and ex-perience, these teenagers will be lesslikely to secure better paying jobs asthey get older.4Fi

Associate Professor of Nursing. Berea College. Written by. Editor. Teresa Partee, MSSW Research Associate Kentucky Youth Advocates, Inc. Margaret Nunnelley, MSSW. Policy Analyst Kentucky Youth Advocates, Inc. a joint project of The Kentucky KIDS COUNT Consortium. and. Kentucky Youth Advocates, Inc. 2034 Frankfort Avenue Louisville, Kentucky .