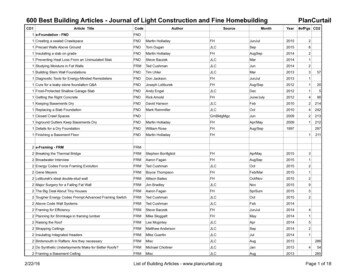

Transcription

ORIGINAL ARTICLESTransforming Health Care from the Inside Out:Advancing Evidence-Based Practice in the21st CenturyELLEN FINEOUT-OVERHOLT, PHD, RN*yBERNADETTE MAZUREK MELNYK, PHD, RN, CPNP/NPP, FAAN, FNAP,z§ALYCE SCHULTZ, PHD, RN, FAANtbHealth care is in need of change. Major professionaland health care organizations as well as federalagencies and policy-making bodies are emphasizingthe importance of evidence-based practice (EBP).Using this problem solving approach to clinical carethat incorporates the conscientious use of currentbest evidence from well designed studies, a clinician’s expertise, and patient values and preferences,nurses and other health care providers can providecare that goes beyond the status quo. Health carethat is evidence-based and conducted in a caringcontext leads to better clinical decisions and patientoutcomes. Gaining knowledge and skills in the EBPprocess provides nurses and other clinicians thetools needed to take ownership of their practicesANDand transform health care. Key elements of a bestpractice culture are EBP mentors, partnerships between academic and clinical settings, EBP champions, clearly written research, time and resources,and administrative support. This article provides anoverview of EBP and offers recommendations foraccelerating the adoption of EBP as a culture ineducation, practice and research. (Index words:Best evidence; Evidence-based practice; Mentorship)J Prof Nurs 21:335–344, 2005. A 2005 Published byElsevier Inc.The Importance of EBP to Health Care*Director, Center for the Advancement of Evidence-BasedPractice, Arizona State University College of Nursing,Tempe, AZ.yAssociate Professor, Clinical Nursing, Arizona State University College of Nursing, Tempe, AZ.zDean and Distinguished Foundation Professor in Nursing,Arizona State University College of Nursing, Tempe, AZ.§Associate Editor, Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing,Tempe, AZ.tProfessor, Clinical Nursing, Arizona State University Collegeof Nursing, Tempe, AZ.bAssociate Director, Center for the Advancement of EvidenceBased Practice, Arizona State University College of Nursing,Tempe, AZ.Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr. FineoutOverholt: Director, Center for the Advancement of EBP, ArizonaState University College of Nursing, Tempe, AZ 85287.8755-7223/ - see front mattern 2005 Published by Elsevier ED PRACTICE (EBP) is aproblem-solving approach to clinical care thatincorporates the conscientious use of current bestevidence from well-designed studies, a clinician’sexpertise, and patient values and preferences (Melnyk& Fineout-Overholt, 2005; Sackett, Straus, Richardson, Rosenberg, & Haynes, 2000). Figure 1 graphically shows these aspects of the EBP process asinterrelated and all having opportunity to affectclinical decisions. In addition, when EBP is providedwithin a context of caring, it leads to the best clinicaldecision making as well as outcomes for patients andtheir families (Melnyk & Fineout-Overholt, 2005).Although it has been empirically supported thatpatient outcomes are at least 28% better when clinicalcare is based on rigorously designed research studiesJournal of Professional Nursing, Vol 21, No 6 (November–December), 2005: pp 335–344335

336FINEOUT-OVERHOLT ET ALFigure 1. Evidence-based practice achieves the best outcomes when accomplished in a context of caring.than when care is steeped in tradition (Heater,Becker, & Olsen, 1988), most nurses are notroutinely implementing EBP. Findings from a recentsurvey to determine nurses’ readiness to engage inEBP conducted by the Nursing Informatics ExpertPanel of the American Academy of Nursing with anationwide sample of 1,097 randomly selectedregistered nurses indicated that (1) almost half werenot familiar with the term bEBP,Q (2) more than halfreported that they did not believe that their colleaguesuse research findings in practice, (3) only 27% of therespondents had been taught how to use electronicdatabases, and (4) most do not search informationdatabases (e.g., MEDLINE and CINAHL) to gatherpractice information—and those who search theseresources do not believe that they have adequatesearching skills (Pravikoff et al., 2005).Because it takes an average of 17 years to translateresearch findings into clinical practice (Balas &Boren, 2000), major professional and health careorganizations as well as federal agencies and policymaking bodies have placed a major emphasis onaccelerating EBP. In the landmark document Crossingthe Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21stCentury (Committee on Quality of Health Care inAmerica, Institute of Medicine, 2001), the Instituteof Medicine designated Rule 5 of the 10 rules forhealth care as evidence-based decision making. Inaddition, the five core competencies for health careeducation deemed necessary by the Institute ofMedicine’s Health Professions Educational Summitincludes using EBP (Greiner & Knebel, 2003). Withsuch growing strong empirical support of EBP,clinicians and consumers must determine how andwhen EBP can be fully embraced as a culture forhealth care. This article provides an overview of EBPand offers recommendations for accelerating theadoption of EBP as a culture in education, practice,and research.The Beginnings of EBPThe EBP movement started in 1972 when a Britishepidemiologist, Dr. Archie Cochrane, criticized themedical profession for not providing the public withrigorous systematic reviews of evidence from existingstudies. He emphasized that thousands of lowbirth-weight premature infants died needlessly because the results of several randomized controlledtrials that supported the effectiveness of administeringcorticosteroids to high-risk women in preterm laborhad not been compiled and analyzed in the form of asystematic review—the strongest level of evidence toguide interventions for clinical practice. When thatsystematic review was finally published, it showedthat corticosteroid therapy reduced the odds ofpremature infant death from 50% to 30% (CochraneCollaboration, 2003).As a result of Dr. Cochrane’s influence, theCochrane Center was established in Oxford, England,in 1992, and the Cochrane Collaboration wasfounded 1 year later. The primary purpose of thecenter and the collaboration is to assist providers inmaking evidence-based decisions about health care by

337TRANSFORMING HEALTH CAREdeveloping, maintaining, and updating systematicreviews of interventions/treatments and by makingthese reviews accessible to the public (CochraneCollaboration, 2003).Although nursing has lagged behind medicine inthe EBP movement, several models have evolved innursing over the past decade to accelerate EBP. Severalof these models are process models (e.g., the Stetlermodel, the DiCenso et al. model, the Iowa model, andthe Rosswurm and Larrabee model [Ciliska, DiCenso,Melnyk, & Stetler, 2005]), and two are mentorshipmodels (the ARCC [Advancing Research and ClinicalPractice Through Close Collaboration] model [Melnyk, Fineout-Overholt, Stone, & Ackerman, 2000]and the Clinical Scholar model [Schultz, 2005]).Although there may be some empirical support forthese models, there must be further testing usingrandomized controlled trials to provide the empiricaldata necessary to support these conceptual models’broad use and proposed intervention strategies. Withevidence to support that mentorship is imperative tothe implementation of EBP (Melnyk et al., 2004;Schultz, 2005), the two mentorship models will bediscussed here; likewise, the two individual clinicianprocess models and the two organizational processmodels will be described.The ARCC ModelThe ARCC model was originally conceptualizedby Bernadette Melnyk in 1999 as part of a researchstrategic planning initiative involving faculty from theUniversity of Rochester School of Nursing andSchool of Medicine in an effort to more fully integrateresearch and clinical practice as well as to advance EBPwithin an academic medical center and progressivehealth care community (Melnyk & Fineout-Overholt,2002). A central concept in the ARCC model is thatof an EBP mentor, an advanced practice nurse within-depth EBP and clinical knowledge and skills whoprovides mentorship in EBP and facilitates improvement in clinical care and patient outcomes throughEBP implementation and outcomes managementprojects. Since its original conceptualization, Melnykand Fineout-Overholt have expanded the ARCCmodel to include multiple strategies for advancingEBP within health care organizations. Specific goalsof the ARCC model include (1) promoting EBPamong both advanced practice and staff nurses locallyand nationally, (2) establishing a cadre of EBPmentors to facilitate EBP in health care organizations,(3) disseminating and facilitating use of the bestevidence from well-designed studies to advance anevidence-based approach to clinical care, (4) conducting an annual national EBP conference, (5) conducting studies to evaluate the effectiveness of theARCC model on the process and outcomes of clinicalcare, and (6) conducting studies to evaluate theeffectiveness of the EBP implementation strategies(Fineout-Overholt, Levin, & Melnyk, 2005; Melnyket al., 2004).The ARCC model has been implemented inseveral agencies, including Pace University, theSUNY Upstate Medical Center, and the Universityof Rochester. These liaisons have fostered empiricaltesting of the ARCC model, and support has beendemonstrated for certain aspects of it. For example,nurses who rate themselves higher on knowledge andbeliefs about EBP are more likely to teach EBP toothers (Melnyk et al., 2004). Furthermore, nurseswho report having an EBP mentor are more likely toimplement evidence-based care (Melnyk & FineoutOverholt, 2002).A pilot study was recently conducted to determinethe effects of the ARCC model on the process andoutcomes of care in two acute care units within a700-bed tertiary care center and four adult units in aspecialty surgery center (Fineout-Overholt et al.,2005). Another pilot study is in process to test themodel within the community via the Visiting NurseService. In addition, two new instruments, the EBPBeliefs Scale and the EBP Implementation Scaledeveloped by Melnyk and Fineout-Overholt, aredemonstrating promise in measuring importantaspects of the ARCC model.The Clinical Scholar ModelThe Clinical Scholar model (Schultz, 2005)reinforces the intellectual processes of EBP, buildinga cadre of mentors who foster an environment inwhich staff nurses are encouraged to continuously askquestions. Clinical scholars are bedside clinicians whochallenge nursing practices through inquiry, observation, analysis, and synthesis of internal data andpublished evidence, application of synthesized evidence, and evaluation of subsequent outcomes.Clinical scholars serve as role models in the ownership of their clinical practice. Inherent in the model isthe final step, dissemination of findings from theprojects and research accomplished by the clinicalscholar team to team members and the health carepublic. Intrinsic to the model are collaboration,consultation, and mentorship by a nurse scientist

338FINEOUT-OVERHOLT ET ALthrough every step of the educational and application processes.Clinical scholars never stop asking why a patient isexhibiting certain signs and symptoms and whethercurrent care practices are the right ones for ameliorating symptomatic challenges. As a role model, aclinical scholar is knowledge oriented and usesresearch as both a product and a process for teachingand managing care. For clinical scholars to assistother team members in navigating through theprocess of using evidence efficiently and generatingevidence effectively, they must have extensive EBPprocess knowledge and skills and the attributes of aclinical leader: creativity, courage, compassion,strength, and vitality (Schultz, 2005).The EBP ProcessThere are five sequential steps to the EBP process.Each step must be carefully considered and executedfor the process to be most successful.STEP 1: ASKING THE CLINICAL QUESTIONThe initial step in EBP is asking a clinical questionin the PICO format (i.e., P patient population,I intervention or area of interest, C comparisonintervention or comparison group, and O outcome). An example of a PICO question is, bIn adults[P], is cognitive–behavior therapy [I] or yoga [C]more effective in reducing depressive symptoms [O]?QThis step in the EBP process has been said to bethe most important and the most challenging one(Sackett et al., 2000). Without formulating asearchable, answerable question, the entire EBPprocess is off to a faulty start. A clinical question thatis searchable and answerable requires answers fromcompleted research, clinical judgment, and patientpreferences. Potential for bias is inherent in the EBPprocess as every patient–clinician situation will requirea different combination of science, clinician judgment, and patient values. In contrast, a researchquestion requires answers from generating/doingresearch with consideration of the amount of biasintroduced to answer the question: minimal whengenerating evidence about interventions and morewhen discussing the meaning of a phenomenon. Themotivation behind a clinical question is what aclinician is to do or how a clinician is to conductpatient care (i.e., practice). The focus of a researchquestion is on generating generalizable knowledge thatwill guide practice. PICO questions require time andfocused energy because the clinical question drives theentire process, starting with an efficient search for thebest evidence to answer the question.STEP 2: SEARCHING FOR THE BEST EVIDENCEThe second step in EBP is searching for andcollecting the best evidence to answer the PICOFigure 2. Levels of evidence for answering clinical questions about the effectiveness of interventions.

339TRANSFORMING HEALTH CAREFigure 3. Levels of evidence for answering clinical questions about meaning.question. The question informs clinicians whichdatabases are appropriate to search, which keywordsto start with in the search, which controlled vocabularyheadings would make the most sense to map onto, andwhich study designs would be most appropriate foranswering the question. Because systematic reviews ofrandomized controlled trials are the strongest level ofevidence (i.e., Level I evidence) to answer questionsabout the efficacy of a certain treatment or intervention, accessing the Cochrane Database of SystematicReviews early in the course of the search is important.The other levels of evidence for a therapy question areshown in Figure 2.If clinicians have a question about the meaning of aconstruct or how one experiences a phenomenon (e.g.,how do parents of a dying child experience grief?),then qualitative evidence is important and a differentleveling of evidence would be appropriate (seeFigure 3). Leveling of evidence can sometimes beconfusing. However, if clinicians focus on the PICOquestion to determine which type of research evidencewould best answer it, then they are less likely to beconfused about what kind of evidence they need toretrieve. Evidence from opinion leaders or authoritiesor reports from expert committees may be necessaryto guide practice when research has not beenconducted; however, interventions based solely onthis type of evidence require diligent, ongoing,rigorous outcomes evaluation for the purpose ofgenerating stronger evidence.STEP 3: CRITICALLY APPRAISING THE EVIDENCEThe third step in EBP is critically appraising theevidence found in the literature search. This criticalappraisal process should be efficient and focus onthree essential questions: (1) Are the results of thestudy or systematic review valid? (i.e., as close to thetruth as possible); (2) What are the results? (i.e., arethey meaningful and reliable—if applied, I can get thesame results); and (3) Are the findings clinicallyrelevant to my patients? For each type of study, thereare subquestions under these three universal questions.The purpose of critical appraisal is to determine thevalue of the research to practice. Much like adiamond, the research will have flaws and limitationsbut will also have some worth to practice. This is ashift in the paradigm of how research is viewed byclinicians. Clinicians should no longer look for astudy’s flaws to eliminate the research but insteadshould view the research for the contribution it canmake to practice, although it may be minimal at times.STEP 4: ADDRESSING THE SUFFICIENCY OF THEEVIDENCE—TO IMPLEMENT OR NOT TO IMPLEMENTThe fourth step in EBP may vary depending onwhether there is valid, reliable, and applicable evidenceto integrate into practice. If such evidence exists, itwould be amalgamated with a clinician’s expertise andpatient preferences to make a decision about patientcare. For example, although the evidence from a seriesof randomized controlled trials supports the use of

340FINEOUT-OVERHOLT ET ALTABLE 1. Selected EBP Process ModelsModelSteps/Phases/ProcessDiCenso, Cullum, Ciliska, and Guyatt (2005) model(1) Asking the question(2) Compiling the evidence(3) Planning a change(4) Integrating skills and experience(1) Generate the question from either a problem or new knowledge(2) Determine relevance to organizational priorities(3) Develop a team to gather and appraise evidence(4) Determine if the evidence answers the question(5a) If there is sufficient evidence, pilot the change in practice(5b) If there is insufficient evidence, generate evidence through research(6) If change is initiated based on the evidence, deemappropriateness of change to practice(7) If appropriate, institute change(8) Evaluate structure, process, and outcome data(9) Disseminate results(1) Assess needs of stakeholders(2) Build relationships and make connections betweennursing intervention and outcome(3) Synthesize the gathered evidence(4) Plan for the evidence-based change in practice(5) Implement the plan and evaluate the implementation(6) Maintain the changePhase 1: PreparationGather evidence; look for confounding influencesPhase 2: ValidationAppraise and synthesize evidencePhase 3: Comparative evaluation/Decision makingDetermine ability of evidence to answer the questionPhase 4: Translation/ApplicationIf there is sufficient evidence, implement it either formally or informallyPhase 5: EvaluationEvaluate whether evidence implementation sufficiently addressed the given issueIowa model (Titler, 2002)Rosswurm and Larrabee (1999) modelStetler (2001) modelAugmentin for unresolved otitis media in children, apractitioner may decide to prescribe Azithromycin if achild refuses to take Augmentin owing to his or herdistaste of the medication.If there is no evidence to answer the clinicalquestion, the fourth step is to generate evidence,either internal evidence through outcomes management initiatives or external evidence through rigorousresearch. Clinical judgment plays a vital role ingenerating or using evidence. Inexperienced cliniciansview patient care differently and may not understandhow a patient’s trajectory or outcomes can beinfluenced by confounding variables; in contrast,experienced, seasoned practitioners often can anticipate the next aspect of a patient’s experience with acertain diagnosis and will view the research differently,using a different set of experiential knowledge andskills. Clinical judgment will also influence howpatient preferences and values are assessed, integrated,and entered into the decision-making process (Benner& Leonard, 2005).STEP 5: EVALUATING THE OUTCOME OF EVIDENCEIMPLEMENTATIONFinally, the fifth step in EBP is evaluating theclinical outcome in a health care provider’s ownsetting. Clinicians must carefully consider appropriateoutcomes to best reflect the success of evidenceimplementation. Use of routinely collected data and/or development of new data collection instrumentscan provide clinicians with outcome data. It isimportant to consider the introduction of bias aswell as confounding influences (e.g., lack of acommon language around EBP concepts) on theoutcomes evaluation. Including patients’ evaluationsof their experience of a program implementation aswell as nurses’ responses enables clinicians to obtain amore comprehensive assessment of the success of theprogram implementation. When evaluating the outcomes of an evidence implementation, it is importantto realize that EBP fosters common goals such asimproved patient care and best practice throughinterdisciplinary collaboration.

TRANSFORMING HEALTH CAREWhat EBP Is and Is NotResearch utilization (RU) was a movement focusedon promoting nurses’ use of research findings in theirpractices. The primary aim was applying a portion ofresearch in a way that was unrelated to the originalstudy (Polit & Beck, 2005). Although this movementserved to heighten the awareness of nurses to thebenefits of research, the tools (e.g., electronic databases and standardized rapid appraisal instruments)were not yet available to help direct care providersreadily access the evidence and evaluate its worth topractice. As a result, synthesis of a body of evidencecould not be a primary focus of RU. Some proponents viewed RU as primarily an organizationalprocess (Horsley, Crane, & Bingle, 1978). Evidencebased practice is far broader than RU in scope;however, RU is part of the process. Evidence-basedpractice requires incorporation of the full body ofbest evidence (i.e., synthesis), clinicians’ expertise andjudgment, and patients’ preferences and values indecision making (Melnyk & Fineout-Overholt,2005) in answering a clinical question. In addition,EBP focuses on outcomes evaluation, either for anapplication of research to practice (e.g., individual orsystemwide) or for ongoing evaluation of practiceparameters (e.g., outcomes management; Melnyk &Fineout-Overholt, 2005). Therefore, it is importantthat nursing leaders clearly understand and define themore comprehensive approach of EBP as comparedwith RU. Although RU and EBP are not synonymous, the work done by pioneers in the RU movement was instrumental in paving the way for EBP tobe more readily embraced.Several models were developed to facilitate RU thatprovided guidance in applying research findings topractice. The Conduct and Utilization of Research inNursing model provides six steps for organizationaluse of research in practice, beginning with identifyinga problem as well as finding research to address it andending with extending the application of findings toother settings (Horsley, Crane, Crabtree, & Wood,1983). The Stetler model focuses on critical thinkingand use of research by a knowledgeable nurse (Ciliskaet al., 2005; Kim, 1999; Stetler & Marram, 1976).The Iowa model focuses on organizational use ofresearch (Titler et al., 1994).EBP PROCESS MODELSIn the past decade, Stetler (2001) and Titler(2002) broadened their scope to include principles ofEBP in their models. Stetler’s model is designed for341use by individual clinicians or by a group of cliniciansto address a particular patient care issue. In hermodel, Stetler described five phases in which clinicians engage to arrive at the best-quality decision andoutcome (see Table 1). The final outcome of theStetler model is evaluation of the use of evidence.DiCenso et al. (2005) also developed a practitionermodel that walks through the steps of the EBP processand culminates in the evaluation of outcome (seeTable 1).The Iowa model is an organizational model thataddresses quality practice from a deductive reasoningapproach. The process by which an issue is addressedis clearly described (see Table 1). The process isinitiated by triggers, either problems or new knowledge that has become available, that are relevant topractice. The process is completed with evaluation ofoutcomes and continues with dissemination offindings (Titler, 2002). Rosswurm and Larrabee(1999) also modeled the EBP process in six steps(see Table 1) that can be adopted by individual nursesor by organizations, with the final step as integrationof change in practice. Although these models havebeen demonstrated to be helpful to practice and havegrowing empirical support regarding their validity,they were not universally adopted.The origins of EBP were steeped in outcomes forpatients (Melnyk & Fineout-Overholt, 2005). Nurseshave long focused on patients as the center of theircare; however, the competing clinical priorities oftoday’s health care system have made maintainingthis focus more challenging (Fineout-Overholt et al.,2005). What is new about EBP is that there are nowspecific criteria for appraising evidence as valid orinvalid, an explicit process to enhance the efficiencyof integrating research into practice with accompanying strategies, and methods for evaluating theoutcome of integrating the EBP process into theculture of an organization. In addition, EBP principles enable nurses to once again own their practicesand to have the tools with which to improve practiceand determine best practices within a complex healthcare system (Strout, 2005).Recommendations for Accelerating EBP inAcademic and Health Care EnvironmentsMultiple barriers that have impeded progress inadvancing EBP in health care settings across theUnited States exist. Some of the major barriers include(1) misperceptions about EBP (e.g., it is too timeconsuming); (2) negative attitudes toward research;

342(3) lack of administrative support; (4) insufficientnumber of EBP mentors and champions in health caresystems; (5) inadequate knowledge, beliefs, and skillsby advanced practice and staff nurses; (6) continuingeducation conferences that are didactic only in nature;and (7) professional educational programs thatcontinue to teach baccalaureate and master’s nursingstudents specifics about how to conduct researchinstead of how to access, efficiently critically appraise,and use studies to improve clinical practice (Melnyket al., 2004; Melnyk, Fineout-Overholt, Stetler, &Allan, 2005).In contrast, studies have supported several facilitators to advance EBP. These include (1) EBP mentorsin health care settings, (2) partnerships betweenacademic and clinical settings, (3) EBP championswithin the environment, (4) clearly written researchsupports, (5) time and resources, and (6) administrative support (Melnyk & Fineout-Overholt, 2002;Melnyk et al., 2004; Omery & Williams, 1999;Schultz, 2005).For the profession of nursing to rapidly acceleratethe EBP paradigm shift, there must be (1) a differentapproach to teaching research and clinical courses inbaccalaureate and master’s degree programs thatemphasizes EBP knowledge and skills; (2) development, testing, and actualization of EBP implementation models in health care organizations; (3) use ofEBP mentors in clinical settings; (4) an acceleration ofintervention studies that test the efficacy of interventions to yield evidence to guide best practices; and(5) an acceleration and funding of translationalresearch to test strategies for disseminating efficaciousinterventions into clinical practice settings.Some of these strategies for accelerating EBPwere identified by a panel of 13 EBP and healthcare experts at the first U.S. Evidence-BasedPractice Leadership Summit, which was held inconjunction with the fifth National EBP Conference, Translating Research into Best Practice withVulnerable Populations, in June 2004 for thepurpose of developing a strategic plan and actioninitiatives to rapidly accelerate EBP throughout theUnited States. The top three priorities for advancing EBP in the United States identified by thisgroup of experts are the following: (1) form anational EBP/research consortium or network ofinstitutions that facilitates the conduct of efficacyand effectiveness studies, (2) implement a nationalEBP mentorship program, and (3) develop standards for integrating EBP into all levels of education(Melnyk et al., 2005).FINEOUT-OVERHOLT ET ALSPECIFIC STRATEGIES FOR ACCELERATING EBPIN EDUCATIONOne of the major challenges in accelerating theEBP paradigm shift is that many baccalaureate andmaster’s nursing educational programs continue toplace an emphasis on teaching students how toconduct research instead of how to access, efficientlycritically appraise, and use research in their clinicalpractices. The end result of an emphasis on theexplicit conduct of studies at these levels is often anegative attitude toward research. In addition,teaching students in-depth critique of researcharticles instead of efficient steps in searching forand rapidly appraising evidence that is foundpromulgates the belief that EBP is an insurmountable feat in the real world, where patient caseloadsand other role responsibilities place inordinatedemands on nurses’ time. Thus, there is an urgentneed for an educational paradigm shift in whichstudents in bachelors and master’s programs aretaught an evidence-based approach to nursingpractice. For this shift to happen quickly, nurseeducators must become educated and skilled inEBP. Preceptors for educational programs also mustbecome skilled in EBP for them to role model theprocess for students they mentor. In addition, EBPmust be consistently threaded throughout bothdidactic and clinical courses where real life caseexamples provide the framework for the EBP processand continual reinforcement through the professional program leads to lifelong learning skills toimprove practice.SPECIFIC STRATEGIES FOR ACCELERATING EBPIN PRACTICEIn health care organizations, an entire culture tosupport EBP must exist. Advance practice and staffnurses as well as administrators must have foundational knowledge as well as strong beliefs about theimportance of EBP and critical skills to supportevidence-based care. There also should be EBPmentors and champions within the system tocontinue to cultivate EBP implementation andoutcomes management projects that will lead toimprovements in patient care and outcomes. Strategies within an organization might include thedevelopment and implementation of ongoing EBProunds in

Journal of Professional Nursing, Vol 21, No 6 (November-December), 2005: pp 335-344 335 *Director, Center for the Advancement of Evidence-Based Practice, Arizona State University College of Nursing, Tempe, AZ. yAssociate Professor, Clinical Nursing, Arizona State Univer-sity College of Nursing, Tempe, AZ.