Transcription

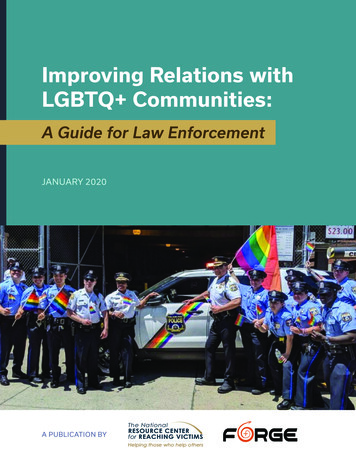

Improving Relations withLGBTQ Communities:A Guide for Law EnforcementJANUARY 2020The NationalA PUBLICATION BYRESOURCE CENTERfor REACHING VICTIMSHelping those who help others

TABLE OF CONTENTSAbout the Publishers. 1About the National Resource Centerfor Reaching Victims.1About FORGE.2Acknowledgements. 4Authors.4Gratitude and Appreciations.4Funding Appreciation.5Introduction & Purpose . 6About this Guide.8Why Should Departments Focus on LGBTQ Issues? . 10History of Policing in LGBTQ Communities. 13Impact of History on LGBTQ andLaw Enforcement Relations Today. 17

10 Ways to Build Stronger Relationshipswith LGBTQ Communities . 20Internal Department Work. 221) Agency Assessments and Internal Inventories . 222) Cultural Awareness and Inclusivity Trainingon LGBTQ Communities. 233) Data Collection on LGBTQ CommunityRelations and Incidents . 314) Recruitment Strategies Inclusiveof LGBTQ Individuals. 335) Policy and Procedure Review, Creation,and Implementation. 35External-Facing Work: Community RelationsWork with LGBTQ Communities. 406) Communication and outreach strategiesfor better LGBTQ relations. 407) LGBTQ Liaison Programming. 428) Community/Law Enforcement Advisory Boardsor Feedback Forums. 469) Participation and Visible Support forLGBTQ Community Events and Celebrations. 4710) Special Initiatives that SupportLGBTQ Communities . 49Closing Note from the Authors . 51Glossary of Terms. 52Endnotes. 58

ABOUT THE PUBLISHERSAbout the National ResourceCenter for Reaching VictimsFunded by the federal Office forVictims of Crime, the NationalResource Center for ReachingVictims (NRC) is a one-stop shopfor victim service providers, culturally specific organizations,justice system professionals, and policymakers to getinformation and expert guidance to enhance their capacityto identify, reach, and serve all victims, especially those fromcommunities that are underrepresented in healing servicesand avenues to justice. The NRC is working to increasethe number of victims who receive healing supports byunderstanding who is underrepresented and why somepeople access services while others don’t, designing andimplementing best practices for connecting people tothe services they need, and empowering and equippingorganizations to provide the most useful and effectiveservices possible to crime victims.The NRC is a collaboration among Caminar Latino, Casa deEsperanza, Common Justice, FORGE, the National Children’sAdvocacy Center, the National Center for Victims of Crime,the National Clearinghouse on Abuse Later in Life, Womenof Color Network, Inc., and the Vera Institute of Justice.The NRC’s vision is that victim services are accessible,culturally appropriate and relevant, and trauma-informed,and that the overwhelming majority of victims accessand benefit from these services. To learn more aboutImproving Relations with LGBTQ Communities: A Guide for Law Enforcement JANUARY 2020The National Resource Center for Reaching Victims reachingvictims.orgFORGE forge-forward.org1

the National Resource Center for Reaching Victims, visitReachingVictims.org.About FORGEFORGE is the nation’s leading organization focused onviolence against transgender/non-binary individuals,founded in 1994. Since 2009, FORGE has held multiplefederal contracts to provide direct services nationwide totransgender/non-binary victims of crime and to providetraining and technical assistance to the victim serviceproviders who work with transgender/non-binary victimsand loved ones.FORGE provides professionals with a wide range of support,including one-to-one technical assistance, virtual trainings,presentations at conferences, customized in-personintensives, and site visits to increase cultural competency.In addition to recorded trainings,FORGE has created and hostsa large, free, online library ofpublications, fact sheets, andother printable resourcesfor providers.FORGE’s mission is to create aworld where all voices, people,and bodies are valued, respected,honored, and celebrated andwhere every individual feelssafe, supported, respected,and empowered. FORGE’s workfocuses around the following fourcentral beliefs: (1) trans peopleImproving Relations with LGBTQ Communities: A Guide for Law Enforcement JANUARY 2020The National Resource Center for Reaching Victims reachingvictims.orgFORGE forge-forward.org2

and loved ones are resilient (but may still benefit fromsome reminders and skills); (2) service providers have theprofession-specific skills they need to serve trans people,but simply need additional trans-specific knowledge andconfidence; (3) every person is valuable and has a great dealto contribute to society; and (4) binary systems and thinkingcreate arbitrary lines between people and communities,which damage spirits and resilience.FORGE is the lead collaborative partner with the NationalResource Center for Reaching Victims, focusing on LGBTQ populations. To learn more about FORGE, please visitforge-forward.org.Improving Relations with LGBTQ Communities: A Guide for Law Enforcement JANUARY 2020The National Resource Center for Reaching Victims reachingvictims.orgFORGE forge-forward.org3

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTSAuthorsRebecca Dreke, MSSWSergeant Michael CrumrineFORGE staff member michael munsonEditing support provided by Kristi Rocap and Alex KapitanGraphic design by Dawn Sword, Serendipity Creative LLCGratitude and AppreciationsFORGE and the authors of this document greatly appreciatethe following individuals and organizations both for theirwork on behalf of and with LGBTQ communities and fortheir willingness to share their experience and perspectivesto help shape this guide:Officers Jim Ritter and Officer Tory Newburn, AssistantChief Adrian Diaz, and Hate Crimes Detective Beth Waringof the Seattle Police Department, along with the Seattlecommunity partners Ken Shulman and Marsha Butzer andfederal partners including Assistant U.S. Attorney BruceMiyake as well as the Hate Crimes taskforce membersfrom the FBI; Lt. Brett Parsons from the Washington DCMetropolitan Police Department; Chief Brian Manley, OfficerGreg Abbink, and Officer Erica Danielle from the AustinPolice Department; Lt. Daniel Meyer and Officer ChristieGarcia from the San Diego Police Department; and SergeantDenise Jones from the Clark County Sheriff’s Office in Ohio.We would also like to extend a heartfelt thank you to allthe members of law enforcement across the country whoImproving Relations with LGBTQ Communities: A Guide for Law Enforcement JANUARY 2020The National Resource Center for Reaching Victims reachingvictims.orgFORGE forge-forward.org4

have worked to improve their departments’ responses toLGBTQ individuals. Your compassionate, thoughtful, andforward-thinking actions have not only improved the livesand well-being of LGBTQ individuals but has made the lawenforcement profession better.Thank you to the Vera Institute of Justice who carefullycoordinates and lifts up the many underserved communitiesrepresented under the National Resource Center forReaching Victims.Funding AppreciationThis product was produced by FORGE, Inc., under award#2016-XV-GX-K015, awarded by the Office for Victimsof Crime, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Departmentof Justice. The opinions, findings, and conclusions orrecommendations expressed in this document are those ofthe contributors and do not necessarily represent the officialpositions or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.Improving Relations with LGBTQ Communities: A Guide for Law Enforcement JANUARY 2020The National Resource Center for Reaching Victims reachingvictims.orgFORGE forge-forward.org5

INTRODUCTION & PURPOSEFORGE and its contributing authors are pleased to presentImproving Relations with LGBTQ Communities: A Guidefor Law Enforcement. This document is intended for use bypolice departments and other law enforcement agencieslooking to create, build, maintain, or restore trust withmembers of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer(LGBTQ )1 communities. The recommendations detailedthroughout can serve as a compendium of practicalsuggestions, ideas for consideration, or a checklist forevaluating current departmental undertakings.Over the past 20 years, much important work has beendone to advance and improve relations between lawenforcement and LGBTQ communities. Historically fraught,this relationship has often been marked by prejudice,discrimination, harassment, and violence. The legacy ofdiscriminatory practices is one that departments must faceand reconcile. Fortunately, in examining problems of thepast including harmful policing practices against LGBTQ populations, many departments have begun taking stepsto build community trust. These efforts are laudable andhave yielded encouraging results; yet there is more workto be done, especially in developing trust between thelaw enforcement and LGBTQ communities of color andyouth. This guide builds on the successful innovations,1 Although “LGBTQ” is the more commonly used, succinct term, the letters do notinclude all who identify with this diverse community. The addition of “ ” throughoutthis guide helps ensure that all those whose sexual orientations and gender identities(or lack thereof) do not conform to societal norms are represented. For a list ofterms, identities, and definitions, please see the glossary of terms at the end of thisdocument.Improving Relations with LGBTQ Communities: A Guide for Law Enforcement JANUARY 2020The National Resource Center for Reaching Victims reachingvictims.orgFORGE forge-forward.org6

recommendations, and best practices of trailblazers inthe field to help motivated departments continue thework. As community leaders, law enforcement not onlyhave a responsibility to help LGBTQ communities accesstheir share of safety and justice, but they also have a realopportunity to support full equality for all citizens.The recommendations presented here are a starting point.Although they are not comprehensive, they can act as abarometer for departments to examine efforts they havealready undertaken. Where possible, resources and linksare provided to exemplary work from jurisdictions aroundthe country.Police departments and law enforcement agencies thathave been successful in successfully building strongeraccountable relations with LGBTQ communities are oftenones that have committed to robust community policingprinciples, including an emphasis on collaboration andoutreach. Local community groups are much better situatedto provide information and assistance regarding the uniqueneeds of their members. Connecting with and creatingongoing collaborations with local organizations to developbest practices specific to that community will yield highquality results for years to come.Connecting with and creating ongoing collaborations withlocal organizations to develop best practices specific to thatcommunity will yield high-quality results for years to come.Improving Relations with LGBTQ Communities: A Guide for Law Enforcement JANUARY 2020The National Resource Center for Reaching Victims reachingvictims.orgFORGE forge-forward.org7

About this GuideAs part of the Vision 21 National Resource Center forReaching Victims project of the Office for Victims of Crime,U.S. Department of Justice, FORGE conducted an extensiveneeds assessment related to challenges and barriers facedby LGBTQ crime victims. For many victims, law enforcement(and the resulting response after an incident) is often thefirst step, or “front door,” to services and resources in theaftermath of a crime. Yet FORGE’s needs assessment showedthat poor, negative, or oppositional relationships with lawenforcement were barriers to reporting for LGBTQ crimevictims. In FORGE’s national work with service providers,victim advocates, and law enforcement, many of thesestakeholders expressed interest in learning more about howto improve police response and enhance the relationshipbetween law enforcement and LGBTQ individuals.FORGE identified two consultants with experienceworking in this arena: (1) a sergeant from a large city policedepartment with years of investigative and policing trainingwork and (2) a former victim advocate and training specialistwho has worked with dozens of police departments acrossthe country to help them improve their responses to crimevictims. These specialists (the authors of this document)conducted a number of site visits in various jurisdictionsthroughout the country, interviewing officers, administrators,community partners, and allied professionals.Throughout the interviews, several common themesemerged on how police departments and other lawenforcement agencies can best demonstrate their desire toimprove community relations.Improving Relations with LGBTQ Communities: A Guide for Law Enforcement JANUARY 2020The National Resource Center for Reaching Victims reachingvictims.orgFORGE forge-forward.org8

These included:ĥThe importance of law enforcement being proactive andvisible in LGBTQ community efforts and eventsĥThe importance of policy and procedure reviewand implementationĥA commitment to restoring strained and fracturedrelationships throughout all ranks (with buy-in stemmingfrom leadership)ĥA willingness to cultivate new relationships andcollaborations—even with entities that might have had afractured relationship with law enforcementĥAcknowledging the real and perceived harms of pastpolicing of this communityĥBeing vocal on specific issues related to safety forthis communityThe departments selected for site visits were just a few ofthe many that have taken proactive steps to create effectivepolicies and procedures to improve relations with theirlocal LGBTQ community. Their successes, challenges, andlessons learned are reflected throughout this compendium.Improving Relations with LGBTQ Communities: A Guide for Law Enforcement JANUARY 2020The National Resource Center for Reaching Victims reachingvictims.orgFORGE forge-forward.org9

WHY SHOULD DEPARTMENTS FOCUS ON LGBTQ ISSUES?LGBTQ individuals are a part of every community inAmerica, including among law enforcement. Somecommunities may contain more LGBTQ people than othersbecause the environment is more conducive for them to liveand express themselves openly, but no community is void ofthem. According to the latest estimate from Gallup,i 4.5% ofAmerican adults, more than 11 million, identify as LGBTQ .iiOf the different age groups listed, 8.1% of Millennials(born between 1980 and 1995) identify as LGBTQ . Onestudy showed that only 47% of “Gen Z” respondents (thoseborn between 1995 and 2012) identify as “exclusivelyheterosexual”; Gen Z respondents reported being far moregender fluid than respondents from previous generations.iiiLaw enforcement will continue to increasingly engageImproving Relations with LGBTQ Communities: A Guide for Law Enforcement JANUARY 2020The National Resource Center for Reaching Victims reachingvictims.orgFORGE forge-forward.org10

LGBTQ communities, and needs the tools to do so in a waythat builds mutual trust and respect.Recent studies also show that some segments of LGBTQ communities have higher rates of victimization than othermarginalized communities, especially LGBTQ communitiesof color.iv Yet many LGBTQ individuals are reluctant tocome forward when they have been victimized or havewitnessed a crime, due to a lack of trust in the criminaljustice system and historically poor relationships with lawenforcement. Some feel they will not be believed whenthey have been the victim of crime, especially in intimatepartner or sexual violence investigations. Some worry theywill become the subject of the investigation instead. Somefear that by contacting law enforcement they will be “outed”as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or queer, and it maynot be safe for this information to be made public. This lackof trust in law enforcement allows perpetrators to go freewithout being held accountable, victims to feel they havenot received justice, and the public’s confidence in lawenforcement professionals to diminish.Nothing destroys a community’s faith in its law enforcementand the criminal justice system more than for communitymembers to feel they cannot access this system when theyare in need. If any community feels they will not be seen,believed, or understood, or if they feel they will not betreated with the same dignity and respect as others, they willnot report when they have been the victim of, or a witnessto, a crime. This gap creates an environment where lawenforcement no longer protects and serves every member ofthe community, perpetuating an “us versus them” narrativethat damages the very essence of community policing. TheImproving Relations with LGBTQ Communities: A Guide for Law Enforcement JANUARY 2020The National Resource Center for Reaching Victims reachingvictims.orgFORGE forge-forward.org11

end result is an erosion in trust that makes it both harder andmore dangerous for law enforcement professionals to dotheir jobs.LGBTQ communities are very diverse, and there areLGBTQ individuals within all other communities—peopleof many different races, ethnicities, faiths, gender identities,abilities, body types, nationalities, sexual orientations,education levels, ages, and income levels. Failure toestablish a strong, respectful, trusting relationship with theLGBTQ community risks law enforcements’ legitimacy withsociety as a whole.Just as communities change while remaining diverse andvibrant, societal institutions must change as well—a tenantthat undergirds community and relational policing. Startingis simple: it begins with acknowledging the mistakes of thepast and vowing to do better. Then engage the communityin honest, open, andmeaningful conversationaround how to makeimprovements. Thesetwo initial steps are thefoundation of mutualtrust and respect, the twoingredients necessaryto foster a positive andlasting relationship withLGBTQ communities.Improving Relations with LGBTQ Communities: A Guide for Law Enforcement JANUARY 2020The National Resource Center for Reaching Victims reachingvictims.orgFORGE forge-forward.org12

HISTORY OF POLICING IN LGBTQ COMMUNITIESTo understand the current distrust of law enforcementby LGBTQ communities, it’s important to considerlaw enforcement’s historical actions with this particularcommunity. When law enforcement began selectivelyenforcing state and local laws that criminalized beingLGBTQ , it effectively became a tool of oppression againstLGBTQ people—for example, selectively enforcing antisodomy laws, as well as punishing public displays ofaffection by same-sex couples. During the mid-20th century,law enforcement routinely engaged in raids that targetedLGBTQ establishments. While law enforcement did notwrite or pass legislation that targeted LGBTQ individuals,law enforcement was the mechanism for enforcing thesediscriminatory practices, sometimes violently.Throughout the history of the United States, local, state, andnational governments—backed by medical and mental healthfields—have criminalized being LGBTQ in myriad ways.Examples include listing homosexuality as a mental disorderby the American Psychiatric Association, anti-sodomylaws that prohibited same-sex sexual acts, and the federalgovernment’s purging of out and suspected homosexuals2from federal work, fearing them to be “security risks.”vIn an effort to identify and remove LGBTQ people fromthe federal government and any federally funded privatecontractor, the FBI engaged state and local police officers tosupply arrest records of thousands of individuals picked up2 Note: the use of the word “homosexual” here is time-bound and was the languageof this time in history.Improving Relations with LGBTQ Communities: A Guide for Law Enforcement JANUARY 2020The National Resource Center for Reaching Victims reachingvictims.orgFORGE forge-forward.org13

for “morality” charges, irrespective of convictions.vi Duringthe 1950s alone, more than 12 million workers, or slightlymore than 20% of the U.S. labor force, faced loyalty-securityinvestigations. Anti-homosexual policies spread from thefederal government to all levels of employment in the UnitedStates. During this time and even up until the present day,many LGBTQ individuals did not feel safe and certainly didnot feel that law enforcement or the criminal justice systemwas there to protect them.On June 28, 1968, the police raided the Stonewall Innunder the pretext of enforcing liquor-licensing infractions.The patrons of the Stonewall Inn, like many other LGBTQ patrons at bars across the country, were accustomed topolice raids, and were fed up with the oppressive tactics ofpolice targeting establishments simply because they werefrequented by LGBTQ individuals. The patrons resistedthe police in an effort to protest the oppressive conduct andstarted a riot. While there were other, smaller responses andrejection of police and government oppression of LGBTQ people during the 1950s and 60s, the Stonewall Riot was awatershed moment and marks the beginning of the modernLGBTQ rights movement. Many Pride celebrations—goingback to the first parade in 1970—are held on June 28 eachyear to commemorate this event.Although the American Psychiatric Association reversedtheir decision on homosexuality in 1973 and holdsthe position that there is no rational basis, scientific orotherwise, to discriminate against or punish LGBTQ individuals, the damage had already been done.vii Manypeople in law enforcement, the criminal justice system, andgovernment continued to persecute LGBTQ individualsImproving Relations with LGBTQ Communities: A Guide for Law Enforcement JANUARY 2020The National Resource Center for Reaching Victims reachingvictims.orgFORGE forge-forward.org14

throughout the remainder of the 20th century. New laws andpolicies were put in place to continue to oppress LGBTQ communities, including “Don’t Ask Don’t Tell” in 1992 andthe “Defense of Marriage Act” in 1996.Although many states either overturned or stoppedenforcing anti-sodomy laws by the later part of the 20thcentury, it was not until 2003 that the U.S. Supreme Courtdeclared in Lawrence v. Texas (539 U.S. 558) that statestatutes prohibiting sexual acts between consenting samesex individuals are unconstitutional. Despite this ruling,several states still have sodomy laws listed in their penalcodes. Not purging these laws sends a message to allmembers of the community that these states do not valueLGBTQ people as fully equal residents, thereby continuingthe reluctance of LGBTQ individuals to trust government.Throughout the rest of the first two decades of the 21stcentury, strides continued toward LGBTQ equality. TheDefense of Marriage Act was ruled unconstitutional, Don’tAsk Don’t Tell was repealed, and in 2015 same-sex marriagewas made legal in the case of Obergefell v. Hodges. In2012, the American Psychiatric Association made a majorannouncement supporting transgender individualsby stating:“Being transgender or gender variant implies no impairmentin judgment, stability, reliability, or general social orvocational capabilities; however, these individuals oftenexperience discrimination due to a lack of civil rightsprotections for their gender identity or expression.Transgender and gender variant persons are frequentlyharassed and discriminated against when seeking housingor applying to jobs or schools, are often victims of violentImproving Relations with LGBTQ Communities: A Guide for Law Enforcement JANUARY 2020The National Resource Center for Reaching Victims reachingvictims.orgFORGE forge-forward.org15

hate crimes, and face challenges in marriage, adoption andparenting rights.”viiiUnfortunately, in today’s culture, law enforcement continuesto have a reputation of being disrespectful and evenphysically threatening to LGBTQ people, particularlytransgender individuals. Similarly, officers report interactionswith transgender people as one of the most challengingLGBTQ issues they face. By focusing reparative efforts ontransgender community relations, law enforcement has theopportunity to create great gains in LGBTQ trust.Implementing policies and procedures is important, butunderstanding the history, acknowledging mistakes, andsincerely vowing never to repeat them not only createscultural competency but establishes legitimacy with thecommunity as a law enforcement entity. It’s as simpleas respect.Improving Relations with LGBTQ Communities: A Guide for Law Enforcement JANUARY 2020The National Resource Center for Reaching Victims reachingvictims.orgFORGE forge-forward.org16

Impact of History on LGBTQ and Law EnforcementRelations TodayNational studies demonstrate ongoing distrust betweenLGBTQ communities and law enforcement. A 2012national survey conducted by Lambda Legal (the nation’soldest and largest LGBTQ nonprofit legal organization)found that 14% of more than 2,300 LGBTQ respondentshad been verbally harassed or mistreated by a policeofficer in the previous five years. Two percent reportedphysical assault and 3% reported sexual harassment by lawenforcement officers.ixA 2015 national survey of transgender individuals(conducted by the National Center for Transgender Equality,with over 27,000 respondents) demonstrated widespreaddistrust of law enforcement.x Of respondents who interactedwith LE officers who thought or knew they were transgenderin the past year, 57% said they were never or only sometimestreated respectfully. Further, 58% reported some formof mistreatment, such as being repeatedly referred to asthe wrong gender, verbally harassed, or physically orsexually assaulted.A 2015 report published by the Williams Institute showedthat, of 73% of respondents who had face-to-face contactwith the police in the previous five years:ĥ21% reported encountering hostile attitudes from officersĥ14% reported verbal assault by the policeĥ3% reported sexual harassment policeĥ2% reported physical assault by law enforcement officersxiImproving Relations with LGBTQ Communities: A Guide for Law Enforcement JANUARY 2020The National Resource Center for Reaching Victims reachingvictims.orgFORGE forge-forward.org17

Abuse, mistreatment, and misconduct by law enforcementwere consistently reported at higher frequencies byrespondents of color and transgender and gender nonconforming respondents.xiiLGBTQ individuals often report that law enforcementdiscrimination and prejudice remains a significant issuefor their communities. A 2017 national study on LGBTQ discrimination showed that nearly 1 in 6 LGBTQ peoplereported being discriminated against when interactingwith law enforcement. This number was much higher forLGBTQ individuals of color.xiii In the same survey, 26%of respondents reported that an LGBTQ friend or familymember had been treated or stopped unfairly by the lawenforcement due to their LGBTQ identity. When askedspecifically about interactions with law enforcement in theirlocal communities, 25% of respondents said lesbian, gay,and bisexual individuals often experienced discriminationduring police interactions; and 32% of respondents reportedthat transgender people experienced police discrimination.LGBTQ victims of crime are less likely to seek services orassistance from police when they need it: 15% of LGBTQ respondents opted not to call the police when in needbecause they feared that they would be discriminatedagainst by police; and LGBTQ people of color were sixtimes more likely than white LGBTQ people to avoid callingthe police when in need of police services. LGBTQ peopleof color consistently report more negative experiences thando white LGBTQ individuals.“LGBTQ victims of crime are less likely to seek services orassistance from police when they need it.”Improving Relations with LGBTQ Communities: A Guide for Law Enforcement JANUARY 2020The National Resource Center for Reaching Victims reachingvictims.orgFORGE forge-forward.org18

Although each police department cannot singularly bear thebrunt or responsibility of decades of police mistreatmentof LGBTQ individuals, there are practical, proactive stepsthat departments can take to help heal the wounds of thepast and advance toward a more equitable experience forall community members. A commitment to change, and awillingness to engage in the process of positive re

The National Resource Center for Reaching Victims reachingvictims.org FORGE forge-forward.org About this Guide As part of the Vision 21 National Resource Center for Reaching Victims project of the Office for Victims of Crime, U.S. Department of Justice, FORGE conducted an extensive needs assessment related to challenges and barriers faced