Transcription

The Sophisticated InnovatorThe Innovation Value ChainRather than reflexively importing innovation best practices, managers should adopta tailored, end-to-end approach to generating, converting, and diffusing ideas.by Morten T. Hansen and Julian BirkinshawMick WigginsEXECUTIVES IN LARGE COMPANIES often ask themselves,“Why aren’t we better at innovation?” After all, there isno shortage of sound advice on how to improve: Comeup with better ideas. Look outside the company forconcepts and partners. Establish different funding mechanisms.Protect the new and radically different businesses from the old.Sharpen the execution.Such strategic counsel, however, is based on the assumptionthat all organizations face the same obstacles to developing newproducts, services, or lines of business. In reality, innovation challenges differ from firm to firm, and otherwise commonly followed advice can be wasteful, even harmful, if applied to thewrong situations.hbr.org1179 Hansen new.indd 121 June 2007 Harvard Business Review 1215/2/07 8:05:09 PM

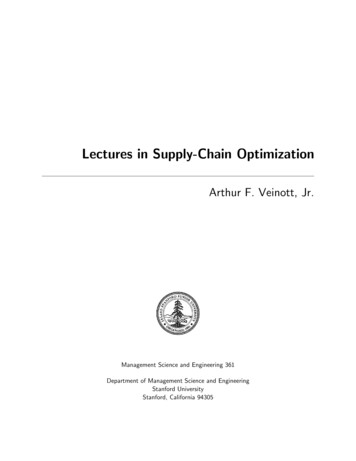

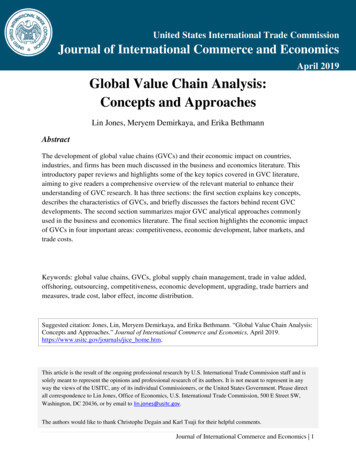

The Sophisticated InnovatorConsider how two different CEOsconfronted the innovation challengesfacing their companies. When SteveBennett joined Intuit, the maker of thefinancial software programs Quickenand QuickBooks, in January 2000, itwas a company with lots of ideas – mostcollected from outside the organization – but little discipline for bringingthose ideas to market. “We had a lot ofenergy focused on learning from customers,” the CEO recalls, “but we werestruggling to decide which ideas wouldhave the highest impact.” To fix this,Bennett demanded that clear businessobjectives be set for ideas in development, and he held people accountablefor delivering on them. Intuit is nowjust as good at executing on ideas as itis at generating them. The company’sArticle at a GlanceThere is no universal solution fororganizations wanting to improve theirability to generate, develop, and disseminate new ideas. Every firm facesits own challenges in this regard.Managers need to take an end-to-endview of their innovation efforts, pinpointtheir particular weaknesses, and tailorinnovation best practices as appropriateto address the deficiencies.The “innovation value chain” offersa comprehensive framework for doingjust that. It breaks innovation downinto three phases (idea generation,conversion, and diffusion) and six critical activities (internal, cross-unit, andexternal sourcing; idea selection anddevelopment; and spread of the idea)performed across those phases.Using the innovation value chain,managers can identify the company’sweaknesses and, as a result, be moreselective about which innovation toolsand approaches to implement. Thechain can also help managers realizethat focusing too many resources onperceived innovation strengths canfurther debilitate the weakest parts ofthe chain – and the company’s overallinnovation capabilities.122 Harvard Business Review1179 Hansen new.indd 122 June 2007revenues and profits are up 47% and65%, respectively, from three years ago,in part because of this effort.About the same time that Bennetttook the helm at Intuit, A.G. Lafleybecame CEO of Procter & Gamble, acompany that had traditionally beengood mainly at developing new products internally and bringing them tomarket. But a persistent weakness wasits insular culture. Lafley wanted thecompany to become better at cultivating ideas from the outside. After fiveyears of investments, P&G now hasa state-of-the-art process for sourcing ideas externally, which includes aglobal network of resources and onlineknowledge-exchange sites. This processcomplements P&G’s core competencyin executing on ideas and has helpedfuel an increase in sales and profits of42% and 84%, respectively, over the pastfive years.Bennett and Lafley faced differentinnovation challenges, which requireddifferent solutions. Intuit and Procter &Gamble probably would be worse offtoday had their CEOs simply importedthe latest best practices in innovationmanagement. Now consider a computer hardware company we analyzed.Buying into the latest advice aboutinnovation – companies should focuson generating more ideas – managersset up a series of formal brainstormingsessions. Idea generation wasn’t theproblem, however. The company hadinadequate screening and funding processes: Concepts never flourished, nordid they die. The brainstorming sessionsactually aggravated the innovation process – employees were pumping moreand more ideas into an already badlybroken system.Even the strongest dose of the bestanalgesic on the market won’t helpmend a broken bone. Likewise, companies can’t just import the latest fads ininnovation to cure what’s ailing them.Instead, they need to consider their existing processes for creating innovations,pinpoint their unique challenges, anddevelop ways to address them. In this article, we offer a comprehensive framework – “the innovation value chain” –for doing just that.The innovation value chain is derived from the findings of five largeresearch projects on innovation thatwe undertook over the past decade. Weinterviewed more than 130 executivesfrom over 30 multinationals in NorthAmerica and Europe. We also surveyed4,000 nonexecutive employees in 15multinationals, and we analyzed innovation effectiveness in 120 new-productdevelopment projects and 100 corporate venturing units.The innovation value chain viewpresents innovation as a sequential,three-phase process that involves ideageneration, idea development, and thediffusion of developed concepts. Acrossall the phases, managers must perform six critical tasks – internal sourcing,cross-unit sourcing, external sourcing,selection, development, and companywide spread of the idea. Each is a linkin the chain. Along the innovationvalue chain, there may be one or moreactivities that a company excels in – thefirm’s strongest links. Conversely, theremay be one or more activities that acompany struggles with – the firm’sweakest links. (See the exhibit “The Innovation Value Chain: An IntegratedFlow.”)Our framework asks executives totake an end-to-end view of their innovation efforts. It discourages managersfrom reflexively importing innovationpractices that may address a part of thechain but not necessarily the one thatthe company needs to improve most.It centers their attention on the weakest links and prompts executives to bemore selective about which practicesto apply in their quest for improved innovation performance.The innovation value chain can alsohelp managers realize that a perceivedinnovation strength may actually turnout to be a weakness: When managerstarget only the strongest links in the innovation value chain – heeding popularadvice for bolstering a core capability in,hbr.org5/2/07 8:05:17 PM

///ggThe Innovation Value Chainsay, idea generation or diffusion – theyoften further debilitate the weakestparts of the chain, compromising theirinnovation capabilities overall.Think Innovation Value ChainTo improve innovation, executivesneed to view the process of transforming ideas into commercial outputs asan integrated flow – rather like MichaelPorter’s value chain for transformingraw materials into finished goods. Thefirst of the three phases in the chain isto generate ideas; this can happen inside a unit, across units in a company,or outside the firm. The second phaseis to convert ideas, or, more specifically,select ideas for funding and developingthem into products or practices. Thethird is to diffuse those products andpractices. Let’s examine the activitiesand challenges associated with each.Idea generation. Executives understand that innovation starts with goodideas – but where do these concepts comefrom? Managers naturally look firstinside their own functional groups orbusiness units for creative sparks; theyusually find they have a pretty goodsense of what’s close at hand. The biggersparks, they discover, are ignited whenfragments of ideas come together –specifically, when individuals acrossunits brainstorm or when companiestap external partners for ideas.Cross-unit collaboration – combining insights and knowledge from different parts of the same company inorder to develop new products andbusinesses – is not easily achieved. Decentralized organizational structuresand geographical dispersion make ithard for people to work across units.Managers at Bertelsmann, the largeMorten T. Hansen (morten.hansen@insead.edu) is a professor of entrepreneurship and theAndré and Rosalie Hoffmann Chaired Professor of Family Enterprise at Insead, in Fontainebleau, France. Julian Birkinshaw (jbirkinshaw@london.edu) is a professor of strategic andinternational management at London Business School and a senior fellow at the AdvancedInstitute of Management Research in London.hbr.org1179 Hansen new.indd 123 German global media company, tooka staggering three years to catch upwith Amazon in launching an onlinebookstore, in large part because oftheir company’s decentralized makeup.Bertelsmann’s autonomous publishing houses, book and music clubs, anddistribution and multimedia divisionscould not and did not collaborate onthis new business opportunity.Companies also need to assesswhether they are sourcing enoughgood ideas from outside the companyand even outside the industry – that is,tapping into the insights and knowledge of customers, end users, competitors, universities, independent entrepreneurs, investors, inventors, scientists,and suppliers. Many companies do thispoorly, resulting in missed opportunities and lower innovation productivity.Sony, for example, had an impressivetrack record throughout the 1980s fordeveloping new-to-the-world productssuch as the Walkman and PlayStation.But by the 1990s, the company’s engineers were becoming increasingly insular. As CEO Sir Howard Stringer recalledJune 2007 Harvard Business Review 1235/2/07 8:05:23 PM

The Sophisticated InnovatorThe Innovation Value Chain: An Integrated FlowViewing innovation as an end-to-end process rather than focusing on a part allows you to spotboth the weakest and the strongest links.CONVERSIONIDEA LSELECTIONDEVELOPMENTSPREADCreationwithin a unitCollaborationacross unitsCollaborationwith partiesoutside thefirmScreening andinitial fundingMovement fromidea to firstresultDisseminationacross theorganizationKEY QUESTIONSDo peoplein our unitcreate goodideas ontheir own?Do we creategood ideas byworking acrossthe company?Do we sourceenough goodideas fromoutside thefirm?Are we goodat screeningand fundingnew ideas?Are we good atturning ideasinto viableproducts, businesses, andbest practices?Are we goodat diffusingdevelopedideas acrossthe company?KEYPERFORMANCEINDICATORSNumber ofhigh-qualityideas generated withina unit.Number ofhigh-qualityideas generatedacross units.Number ofhigh-qualityideas generated fromoutside thefirm.Percentageof all ideasgenerated thatend up beingselected andfunded.Percentage offunded ideasthat lead to revenues; numberof months tofirst sale.Percentageof penetration in desiredmarkets, channels, customergroups; numberof months tofull diffusion.and headaches across the organization.In many companies, tight budgets, conventional thinking, and strict fundingcriteria combine to shut down mostnovel ideas. Employees quickly get themessage, and the flow of ideas dries up.When Stewart Davies became head ofR&D at BT in 1999, the UK telecommunications group was in financial trouble. Davies reviewed operations withinR&D and recalled being staggered bythe inventiveness – and the frustration – of the people he met. There wasno shortage of good ideas at the company, he concluded. But inadequatecommercial skills and a shortage ofseed money for high-risk projects madeit difficult for anyone to move forwardwith ideas for new technologies.in a 2005 New Yorker article, the engineers started to suffer from a damaging“not invented here syndrome,” even asrivals were introducing next-generationproducts such as the iPod and Xbox. Asa result of their belief that outside ideaswere not as good as inside ones, theymissed opportunities in such areas asMP3 players and flat-screen TVs and developed unwanted products – camerasthat weren’t compatible with the mostpopular forms of memory, for instance.Idea conversion. Generating lots ofgood ideas is one thing; how you handle (or mishandle) them once you havethem is another matter entirely. Newconcepts won’t prosper without strongscreening and funding mechanisms.Instead, they’ll just create bottlenecks124 Harvard Business Review1179 Hansen new.indd 124 June 2007 Other companies have the oppositeproblem: Managers don’t apply theirscreens strictly enough. The organization overflows with new projects ofvarying quality (often underfundedand understaffed) and no clear senseof how the initiatives fit into the overarching corporate strategy. For instance,in 1999 the UK media company Emapearmarked approximately 100 millionto create a digital division to developInternet-based offerings for its magazine and radio businesses. Worried thatit was falling behind its competitors,the company aggressively invested inwhatever digital business ideas wereput forward, with little regard for business cases or budgets. By 2000, Emaphad 43 separate businesses focused onhbr.org5/2/07 8:05:32 PM

///ggThe Innovation Value Chainonline media offerings, with projectedrevenues in excess of 100 million. In reality, revenues never rose above 20 million. Most of the businesses shut theirdoors; and the division reported lossesof 60 million in 2001 and 17 millionin 2002.No matter how well screened orfunded, ideas still must be turned intorevenue-generating products, services,and processes. Concepts that have beenselected for further development oftengo nowhere because they’re languishing in a part of the organization that’stoo busy doing other things or thatfails to see their potential. For instance,to address the burgeoning demand forenergy-efficient lighting, consumer appliances, and heating systems, GeneralElectric invested in a small energymanagement services business in Canada in the 1990s. Despite the business’searly successes in winning contractsand some market share, there was nonatural home for it within the product-focused GE. The business struggledalong as a misfit for a few years beforebeing shut down, and GE missed an opportunity to gain early-mover advantage in a growing industry.Idea diffusion. Concepts that havebeen sourced, vetted, funded, and developed still need to receive buy in – andnot just from customers. Companiesmust get the relevant constituencieswithin the organization to supportand spread the new products, businesses, and practices across desirablegeographic locations, channels, andcustomer groups. In large companieswith many subsidiaries and organizations, such diffusion is far from automatic. At Procter & Gamble in Europe, for instance, the focus severalyears ago was on extensive productand market testing to prove “superiortotal value,” and the company placedultimate authority for launching newproducts on the shoulders of its national brand managers. These policiesled to painfully slow rollouts. Becauseof P&G’s rigorous market-test requirements, managers launched Pampersdiapers in France an astonishing fiveyears after the product was first introduced in Germany. Meanwhile, ColgatePalmolive, noticing P&G’s early successin Germany, launched a me-too line ofdiapers in France, gaining dominantmarket share there, two full years before P&G introduced Pampers in thatcountry.Focus on the Right LinksWhen executives view their companies’ innovation processes as a valuechain, engaging in a link-by-link analysis, they may be surprised by whatthey learn. The managers we’ve workedwith are often quick to tout their particular innovation strengths: “We’rereally creative.” “We’re very good at developing products fast.” Perhaps – butthese so-called innovation strengthscan actually lead to weaknesses inthe process if they’re not complemented by equivalent strengths inother areas. Consider the computerhardware manufacturer we referredto earlier. At any point in time, therewere at least 50 very good ideas fornew products and businesses floating around the company. But becausemanagers did not screen the ideasproperly – funding the best ones andkilling the others – few ideas took hold,and new ones just kept coming. Theengineers at the firm became increasingly frustrated, seeing their creativetalents go to waste. The brainstormingsessions that senior management implemented to help mend fences withthe engineers only contributed to theproblem. By failing to recognize theweak link (idea selection) and focusingmore time and resources on an alreadystrong link (idea generation), the management team undermined the company’s overall innovation efforts.Similarly, it doesn’t matter how greata company’s idea-selection process is ifonly a few good concepts are on thetable or if the subsequent developmentprocess is weak. It’s also a waste of timeand money to develop state-of-the-artcapabilities for rolling out products orhbr.org1179 Hansen new.indd 125 services when there’s nothing worthwhile to diffuse.In short, a company’s strongest innovation links are simply no good ifthey prompt the organization to spendmoney with little hope of solid returnsor if the attention paid to them furtherweakens other parts of the innovationvalue chain. Managers need to stop putting all their effort into improving theircore innovation capabilities and focusinstead on strengthening their weaklinks. Indeed, our research suggests thata company’s capacity to innovate is onlyas good as the weakest link in its innovation value chain. (See the exhibit “WhichInnovation Strategy Is Right for You?”)Organizations typically fall into oneof three broad “weakest link” scenarios.First is the idea-poor company, whichspends a lot of time and money developing and diffusing mediocre ideas thatresult in mediocre products and financial returns. The problem is in idea generation, not execution.By contrast, the conversion-poor company has lots of good ideas, but managers don’t screen and develop themproperly. Instead, ideas die in budgetingprocesses that emphasize the incremental and the certain, not the novel. Ormanagers adopt the “1,000 flowers” approach, letting ideas bloom where theymay but never culling them. The needis for better screening capabilities, notbetter idea generation mechanisms.Finally, the diffusion-poor companyhas trouble monetizing its good ideas.Decisions about what to bring to marketare made locally, and not-invented-herethinking dominates. As a result, newproducts and services aren’t properlyrolled out across geographic locations,distribution channels, or customergroups. For such companies, the realupside lies in aggressively monetizingwhat it has already been able to develop, not in paying further attentionto idea generation or idea conversion.Here’s a closer look at the three typical weakest-link scenarios and somepossible best practices that would beappropriate for managers to adopt.June 2007 Harvard Business Review 1255/2/07 8:05:38 PM

The Sophisticated InnovatorFixing the Idea-Poor Companytect fatty acids from oxidation?” – thatany of the more than 10,000 engineers,chemists, and other scientists registeredat the site can tackle. The individual orgroup offering the best acceptable solution gets a financial reward; the winnerof the fatty acids challenge received 20,000.The second approach is to build adiscovery network geared towardunearthing new ideas within broadtechnology or product domains. Thisis what Siemens, the Germany-basedelectronics and engineering company,has done in Silicon Valley. Since 1999,it has sited a 15-person scouting unit inBerkeley, California. Members of theTechnology-to-Business (TTB) Centercultivate personal relationships withscientists, doctoral students, ventureWhy do some companies experiencea shortage of good new ideas? Our research indicates it’s partly due to inadequate networks. Managers fail toforge quality links with others outsidetheir company. Or people prefer to talkto their immediate colleagues ratherthan reach out to counterparts in otherdepartments or divisions. These companies need to build external networksas well as internal cross-unit networksto generate ideas from new connections.Build external networks. Thereare two fundamentally different approaches to building external networks,each of which fulfills different objectives. The first approach is to developa solution network, geared toward finding answers to specific problems. ThisA company’s capacity to innovate is only as good as theweakest link in its innovation value chain.capitalists, and entrepreneurs as well asgovernment labs and corporate researchcenters. Through these relationships,they learn about emerging technologies and business ideas. Their real valueas scouts, though, lies in their abilityto match emerging technologies to specific Siemens businesses. For instance,TTB scouts learned about technologyfor optimizing the quality of service oncomputer networks from a ColumbiaUniversity doctoral student. They wereable to deliver that knowledge to theappropriate parties – first to Siemens’stelecommunications division, and then,after that industry experienced an unrelated downturn, to the company’sfactory communications division. Thatgroup aspired to meet the customerneed for guaranteed real-time traffic over wireless local area networks(WLAN). As a result of TTB’s diverseexternal network, Siemens was able torelease the first-ever WLAN productis what A.G. Lafley mainly has builtat P&G. In-house product developerstranslate customer needs into technology briefs that include descriptions ofthe problems to be solved. The technology briefs traverse the company’s external network – which comprises technology scouts, suppliers, research labs, andretailers worldwide – to see whethersomeone, somewhere can offer solutions to the problems posted. (For moredetails about P&G’s external solutionnetwork, see Larry Huston and NabilSakkab’s “Connect and Develop: InsideProcter & Gamble’s New Model for Innovation,” HBR March 2006.)Likewise, the pharmaceutical company Eli Lilly has spearheaded InnoCentive (www.innocentive.com), a solution-seeking Web site that Lilly, P&G,and other companies use to find answers to specific technical or scientificproblems. The companies post questions – for instance, “How can we pro-126 Harvard Business Review1179 Hansen new.indd 126 June 2007 with real-time guarantees and take aleading place in that market.The objective of discovery networksshould be to learn, not to tell. Considerhow Intuit developed its Simple Startedition of QuickBooks in 2003. Developers wanted to observe the ownersof one- or two-person businesses: Exactly how did they manage their accounts? How did they handle their payables and receivables? Intuit created afact-finding process: A ten-member development team visited with small business owners in 40 “follow me homes,”where the developers experienced firsthand the business problems facing users.Many customers didn’t need or wantcertain higher-end accounting functions in their software, the developerslearned, so the team set out to simplifyQuickBooks. They tested six successivestripped-down versions of the softwarein the follow-me-homes before arriving at the Simple Start edition – whichproved to be a best seller for Intuit.Whether managers are developing solution networks or discoverynetworks, the key metric for them tokeep in mind is diversity, not number,of contacts. The goal here should beto tap as many unique sources of information and ideas as possible as opposed to interacting with many similar contacts.Build internal cross-unit networks.A complementary approach to generating new ideas from outside companiesis to build cross-unit networks insideorganizations. After all, employees whodon’t know one another can’t collaborate on new ideas. And the occasionalcross-functional brainstorming sessionwon’t do the trick: It unfairly assumesthat people who are unfamiliar withone another will be able to work together to generate ideas on demand.What’s needed is an ongoing dialogueand knowledge exchange between people from different units.P&G has done this for years, resulting in many successful cross-fertilizedproduct and business creations. Take,for example, the company’s develop-hbr.org5/2/07 8:05:49 PM

///ggThe Innovation Value ChainWhich Innovation Strategy Is Right for You?There are many excellent innovation perspectives, as this small sample of published works indicates. The innovation valuechain provides a framework for managers to sort out which approaches make the most sense for their companies to adopt.Innovation Value ChainPossible SolutionIn-house ideageneration“How to Kill Creativity,” by Teresa M. Amabile (HBR September–October 1998)Crosspollination“Collaboration Rules,” by Philip Evans and Bob Wolf (HBR July–August 2005)IdeaGenerationExternalsourcingJamming: The Art and Discipline of Business Creativity, by John Kao (HarperBusiness, 1996)“Coevolving: At Last, a Way to Make Synergies Work,” by Kathleen M. Eisenhardt andD. Charles Galunic (HBR January–February 2000)Democratizing Innovation, by Eric von Hippel (MIT Press, 2005)Blue Ocean Strategy, by W. Chan Kim and Renée Mauborgne (Harvard Business SchoolPress, 2004)Open Innovation: The New Imperative for Creating and Profiting from Technology, by HenryChesbrough (Harvard Business School Press, 2003)Selection“Bringing Silicon Valley Inside,” by Gary Hamel (HBR September–October 1999)Corporate Venturing: Creating New Businesses Within the Firm, by Zenas Block and Ian C.MacMillan (Harvard Business School Press, 1993)ConversionDevelopment10 Rules for Strategic Innovators: From Idea to Execution, by Vijay Govindarajan andChris Trimble (Harvard Business School Press, 2005)The Innovator’s Solution: Creating and Sustaining Successful Growth, by Clayton M.Christensen and Michael E. Raynor (Harvard Business School Press, 2003)DiffusionSpread ofthe ideaPayback: Reaping the Rewards of Innovation, by Harold L. Sirkin, James P. Andrew, andJohn Butman (Harvard Business School Press, 2007)“Tipping Point Leadership,” by W. Chan Kim and Renée Mauborgne (HBR April 2003)ment of Olay Daily Facials. The ideawas to make a face cream that was anexcellent cleanser and moisturizer. Experts from P&G’s skin care, tissue andpaper towel, and detergents and fabric softeners groups joined together,and their combined knowledge aboutsurfactants, substrates, and fragranceshelped P&G create and launch a highlysuccessful new product.These kinds of collaborations don’thappen by chance; they are the result of well-established organizationalmechanisms. P&G has developed 30communities of practice. Each comprises volunteers from different partsof the organization and is built aroundan area of expertise (such as fragrance,bleach, analytical chemistry, or skin andhair science). The teams solve specificproblems that are brought to them,and they participate in monthly technology summits with representativesfrom P&G’s ten business units. Thecompany has also posted an “ask me”feature on its intranet, where employees can describe a business problem orneed. Their questions or concerns getpushed out to 10,000 P&G employeesworldwide and are ultimately funneledto those people with relevant expertise.At a more fundamental level, P&G promotes from within and moves peopleacross countries and units. As a result,its employees build extensive personalcross-unit networks.hbr.org1179 Hansen new.indd 127 Fixing the Conversion-PoorCompanyWhy do companies find it difficult toconvert good ideas into products andservices? Most companies have noshortage of formal systems for managing ideas. The number and diversity ofpeople involved, however, can createa risk-averse and bureaucratic processthat grinds execution to a halt. As onesenior executive in a financial servicescompany told us, “If I want to get a newidea to market quickly, I take personalcontrol of it, and I steer it through thesystem. If I want to kill an idea, I sendit through the formal process.” Two innovation practices can go a long waytoward addressing the idea-conversionJune 2007 Harvard Business Review 1275/2/07 8:05:55 PM

The Sophisticated Innovatorand progress reviews are required ateach stage. Ventures that achieve “proofof concept” (about 10% of all originalsubmissions) leave GameChanger atthat point and are either moved intoone of the divisions (where most projects go) or into Shell Technology Ventures, a corporate spinout vehicle.Since GameChanger was formed,some 1,600 ideas have been submitted.The flow of proposals is constant, andthe unit has built up a track record ofsuccess: forty percent of all development projects in the exploration andproduction business started out asGameChanger ventures.Safe havens. Some companies arebetter than others at building safe havens for their emerging concepts. Suchhavens can be critical to the successfulconversion of good ideas into profitableproducts or businesses. Consider theproblem – multichannel funding andsafe havens.Multichannel funding. In conversion-poor companies, innovation stallswhen, say, the boss doesn’t like a particular new idea or doesn’t consider itgood enough to supplant an existinginitiative that’s already accounted forin the budget. That’s usually the endof it; another potential line of businessor method for improving corporate performance falls by the wayside. A multichannel funding model, however, opensup different options outside the boss’simmediate purview – from small discretionary pots of seed money all theway to full-scale venture funds.Consider the success of Shell Oil’sGameChanger unit: It was set up in1996 to fund the development of radical ideas that might lead to entirelynew businesses, and it has been a greatincluded heavy-hitting line executivesoversaw the new ventures. When onenew business team was looking for access to an existing Tenco sales channel,a board member was able to broker thematch in a wa

years of investments, P&G now has a state-of-the-art process for sourc-ing ideas externally, which includes a global network of resources and online knowledge-exchange sites. This process complements P&G's core competency in executing on ideas and has helped fuel an increase in sales and profi ts of 42% and 84%, respectively, over the past