Transcription

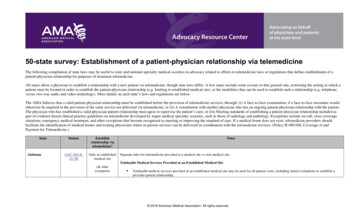

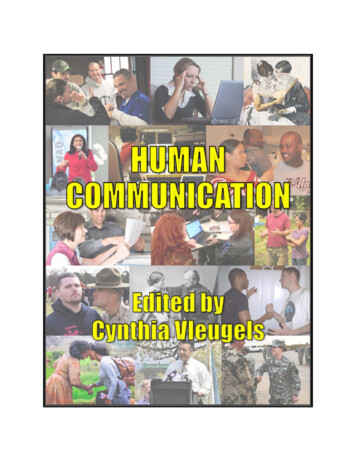

Patient-Provider CommunicationRoles for Speech-Language Pathologists and Other Health Care ProfessionalsPatient-Provider Communication: Roles for Speech-LanguagePathologists and Other Health Care Professionals presents timelyinformation regarding effective patient-centered communicationin a variety of health care settings. Speech-language pathologists(SLPs) and professionals from medical and allied health fields aswell as those who serve the communication needs of childrenand adults with communication challenges will benefit from thisvaluable resource.This text is a particularly relevant resource with the recentenactment of the Affordable Care Act and focuses on value-basedcare, communication support, and outcomes related to positivepatient experiences for a range of communication-vulnerablepatients--including individuals with speech and languagedisorders, as well as health literacy, cultural, and languagefactors. Additional, topics addressed include: medical education,adult and pediatric acute care settings, rehabilitation, long-termresidential care, and hospice/palliative care situations.The editors are recognized internationally for their work in thefield of communication disorders and have been active in the area of patient-provider communication formany years. Patient-Provider Communication is a must-have resource to ensure SLPs and other healthcare providers are at the forefront of quality patient-centered care.Book DetailsEditors: Sarah Blackstone, PhD, CCC-SLP, David Beukelman, PhD, CCC-SLP, Kathryn Yorkston, PhD, CCC-SLPISBN: 978-1-59756-574-5 Price: 99.95 325 pages, Illustrated (B/W), Softcover Released: April 2015Visit http://www.pluralpublishing.com/publication ppc.htm to learn more about Patient-ProviderCommunication or to place an order. To arrange a bulk order or a book review, contact PluralPublishing’s marketing team at marketing@pluralpublishing.com.About Plural Publishing, Inc.Plural Publishing produces leading academic, scientific and clinical publications in the fields of speechlanguage pathology, audiology, otolaryngology, and professional singing. Plural Publishing, Inc. aims tofill a space in the field of communication sciences and disorders with high-quality publications written byworld-class experts in order to improve and enhance the knowledge base of each profession, from theclassroom to clinical practice. Plural Publishing prioritizes the intellectual growth of the disciplines itserves and strives to improve and advance these fields through its publications.www.pluralpublishing.com

ContentsPreface viiContributors ixChapter 1.Building Bridges to Effective Patient-Provider CommunicationSarah W. Blackstone, David R. Beukelman, and Kathryn M. Yorkston1Chapter 2.Issues and Challenges in Advancing Effective Patient-ProviderCommunicationSarah W. Blackstone9Chapter 3.Medical Education: Preparing Professionals to EnhanceCommunication Access in Health Care SettingsKathryn M. Yorkston, Carolyn R. Baylor, Michael I. Burns,Megan A. Morris, and Thomas E. McNalley37Chapter 4.Enhancing Communication in Outpatient Medical Clinic VisitsKathryn M. Yorkston, Carolyn R. Baylor, Michael I. Burns,Megan A. Morris, and Thomas E. McNalley73Chapter 5.Integrating Emergency and Disaster Resilience Into YourEveryday PracticeSarah W. Blackstone and June Isaacson Kailes103Chapter 6.Adult Acute and Intensive Care in HospitalsRichard R. Hurtig, Marci Lee Nilsen, Mary Beth Happ, andSarah W. Blackstone139Chapter 7.Pediatric Acute and Intensive Care in HospitalsJohn M. Costello, Rachel M. Santiago, and Sarah W. Blackstone187Chapter 8.Patient-Provider Communication in Rehabilitation SettingsDavid R. Beukelman and Amy S. Nordness225Chapter 9.Residential Long-Term CareDavid R. Beukelman247Chapter 10. Enhancing Communication in Hospice SettingsLisa G. Bardach271Chapter 11. Making It Happen: Moving Toward Full ImplementationSarah W. Blackstone, David R. Beukelman, and Kathryn M. Yorkston303Index 321v

PrefaceAs we wrote this book, the authors becameincreasingly aware that patients, health careproviders, policy makers, and researcherslive in nearly parallel universes with differingincentives, access to data and information,accountability expectations, and time framesfor action (see Chapter 1). Patient-ProviderCommunication: Roles for Speech-LanguagePathologists and Other Health Care Professionals was written in an effort to bridge thedifferences between the perspectives of communication vulnerable patients and thosewho provide their health care services anddevelop health care policies that guide theircare. The clinicians, educators, and researcherswho authored chapters in this text have provided strong evidence of the need for effectivepatient-provider communication across thecontinuum of health care. This book documents policies and the clinical practices thatare currently being implemented to facilitatemedical encounters among health care providers, communication vulnerable patients, andfamily members in doctor’s offices/clinics,emergency/disaster scenarios, acute-care hospitals, rehabilitation hospitals, nursing homes,long-term care facilities, and hospice settings.Examples of communication support materials, technologies, and strategies are providedfor communication vulnerable patients due to(a) preexisting medical conditions, (b) recenthealth conditions or interventions, (c) language or cultural differences with health careproviders, and (d) limited health literacy.Individual chapters focus on the challenges and complexities associated withpatient-provider communication across healthcare settings. Chapter 1 highlights the paralleluniverses of the four groups of people potentially involved in patient-provider communi-cation — patients, policy makers, researchers,and health care providers. Chapter 2 sets thestage by exploring the inherent complexityof medical encounters, recognizing that eachencounter involves not only a patient (as wellas family members) who may (or may not)have difficulty communicating, a provider (orperhaps a team of professionals) who may (ormay not) have difficulty jointly establishingmeaning with patients, and contextual variables that relate specifically to the medicalencounter, as well as social, linguistic, cultural,geographical, and other situational factors.Chapter 3 explores issues related to professional education and introduces some excitingnew teaching strategies, emphasizing the needfor interprofessional practice. It also introduces the need to develop continuing education programs that address patient-providercommunication, a theme echoed throughoutthe book. Chapters 4 through 10 spotlight“communication” issues that occur acrossmedical settings. Authors discuss patientprovider communication in doctor’s offices orclinics (Chapter 4); during a medical emergency or disaster (Chapter 5); in an acute carehospital/intensive care unit for adults (Chapter 6) or for children (Chapter 7); in rehabilitation facilities (Chapter 8); in long-term carefacilities (Chapter 9); and finally, in hospicesettings (Chapter 10). These situational chapters illustrate different communication contexts and how communication interventionsmay work in each. They also demonstrate theimmediate and quantifiably positive impacteffective communication interventions haveon patient engagement, care, safety, satisfaction, and outcomes. Finally, Chapter 11 lookstoward the future and identifies exciting nextsteps, trends, and opportunities.vii

viii Patient-Provider CommunicationThe unique roles of speech-languagepathologists in the provision of communication support services are described throughout the book. These communication supportinterventions are illustrated with numerousreports of patient experiences in various medical settings. The identity of these patientsis protected in that their names have beenchanged, and a few of the descriptions arecomposite case reports to illustrate the experiences of patients with similar communication vulnerabilities. We wish to thank thosepatients whose personal stories illustrate awide range of patient-provider communication barriers and solutions.We thank our coauthors whose namesare listed on the individual chapters to whichthey contributed, and we acknowledge the following professionals who served as consultantsin their unique areas of expertise:Linda Bender, Lead Clinical SocialWorker, Arbor Hospice, Ann Arbor,MichiganBarbara Collier, SLP, Executive Director,Communication Disabilities AccessCanada, Toronto, CanadaBecky Cornett, SLP, Director of StrategicPlanning, Wexner Medical Center, TheOhio State University, Columbus, OhioAbby Davis, SLP, Tabitha Home CareServices, Lincoln, NebraskaBrian Dempsey, Chief, Seaside FireDepartment, Seaside, CaliforniaRebecca DeRaud, Social Work andBereavement Manager, Angela Hospice,Livonia, MichiganMary Curet Duranti, Director, DisabilityResource Center, University of PittsburghMedical Center (UPMC), Pittsburgh,PennsylvaniaGail Finsand, SLP, Extended Care Unit& Outpatient Rehabilitation, MadonnaRehabilitation Hospital, Lincoln,NebraskaRobin Pollens, SLP, Reverence HomeHealth and Hospice & Adjunct AssistantProfessor, Western Michigan University,Kalamazoo MichiganHarvey Pressman, President, CentralCoast Children’s Foundation; Co-chair,Patient Provider Communication Forum,Monterey, CaliforniaPaul Rao, SLP, Former President, ASHA,Rehabilitation Consultant, NationalRehabilitation Hospital, Washington, DCKarin Ruschke, President and Founderof International Language Services, Inc.,Chicago, IllinoisAmy Wilson-Stronks, Founder, WilsonStronks, LLC Improving Healthcare,Chesterton, IndianaCheryl Wagoner, SLP, Long-termAcute Care Hospital Unit, MadonnaRehabilitation Specialty Hospital,Bellevue, NebraskaWendy Walsh, Homeland Defense &Security Coordinator, Naval PostgraduateSchool, Monterey, CaliforniaCarrie Windhorst, SLP, Long-termAcute Care Hospital Unit, MadonnaRehabilitation Hospital, Lincoln,NebraskaFinally, the editors of this book thankHeidi Menard who proofed and formattedthe chapter manuscripts. In addition, we haveappreciated the support and encouragementfrom Valerie Johns, Milgem Rabanera, KalieKoscielak, Rachel Singer, and Megan Carterfrom Plural Publishing, Inc.

Chapter 2Issues and Challenges in AdvancingEffective Patient-ProviderCommunicationSarah W. BlackstoneIntroductioncuss the nature of communication betweenpatients and providers across the continuumof health care, identify populations who are“communication vulnerable,” discuss opportunities for speech-language pathologists andother providers to improve patient-providercommunication across health care settings,and give examples of promising practices during medical encounters. This chapter sets thestage for more detailed discussions of specifichealth care settings in later chapters.Given the diversity of patients, providers,medical encounters, and health care settings,as well as the complexity of the messages thatneed to be conveyed, successful communication between patients and providers is not easilyachieved. “Communication access” is, nevertheless, mandated by law, policy, and regulations in the United States and other Westernnations. This means that health care systemsand the professionals who work in them needto develop a better understanding of factorsthat influence successful patient-provider communication so they can prevent or amelioratecommunication breakdowns. Communication access involves consideration of face-toface interactions between two people or in agroup situation; telephone communication;Communication between patients and providers is a core component of patient-centeredand value-based health care. In Chapter 1 wenoted that policy makers, administrators,researchers, and providers across the continuum of health care are beginning to addressthis component more fully, forcefully, and systematically. Research shows that communication breakdowns can lead to negative healthoutcomes, increased costs, lack of adherenceto provider recommendations, longer staysin intensive care units (ICUs), longer hospital stays, increased hospital readmissions, anincrease in sentinel events, and reduced patientsatisfaction (Bartlett, Blais, & Tamblyn, 2008;The Joint Comission, 2013). Evidence alsoreveals that successful patient-provider communication correlates positively with patientsafety and satisfaction, better health outcomes, adherence to recommended treatment,self-management of disease, and lower costs(Bartlett, Blais, & Tamblyn, 2008; Divi, Koss,Schmaltz, & Loeb, 2007; Wilson-Stronks &Galvez, 2007; Wolf, Lehman, Quinlin, Zullo,& Hoffman, 2008). In this chapter, we dis9

10 Patient-Provider Communicationreading and handling text and print materials; use of the Internet, e-communicationsand social media; and written communication(Collier, Blackstone, & Taylor, 2012).Defining CommunicationCommunication is so embedded in oureveryday lives that we rarely think about howcomplex it truly is. Theoretical constructsof communication (whether or not they areexplicitly understood, known, or stated) helpshape our daily practice and research andinfluence what constitutes best practice, whatis considered relevant evidence, and how evidence is interpreted (Blackstone, Wilkins, &Williams, 2007).An early construct of the human communication process was the “sender-receiver”model of communication (Shannon & Weaver,1949). This widely held and persistent theoryconceptualized human communication asconsisting of a sender, a channel, and a receiver.As applied within the context of health care,the sender-receiver model led to expectationsthat a provider (e.g., a physician or a speechlanguage pathologist) “sends” information toa patient during a medical encounter (e.g., anoffice visit, at bedside) and then assumes thepatient has understood/“received” the information conveyed, which may or may notbe the case. Interference from the “channel”during face-to-face communication is oftenillustrated by the “telephone game” wherein amessage is whispered in the ear of one personafter another, clearly demonstrating how easily messages can be distorted without eitherthe sender or receiver being aware. As GeorgeBernard Shaw pointed out, “the single biggestproblem with communication is the illusionthat it has taken place.”The sender-receiver model is far too simplistic a view of human communication. Forstarters, face-to-face interaction involves mul-tiple channels (e.g., information is transmittednonverbally as well as verbally). A more robustand workable construct also requires recognition that human communication is part of aninteractive, dynamic social process and thusnecessitates consideration of factors that gobeyond the individuals involved, taking intoaccount underlying cultural components andkey aspects of the environment.The communication accommodationtheory (Giles & Ogay, 2007) recognizes thatspeakers and listeners accommodate eachother’s communication patterns during socialinteractions. One interesting application ofthe theory is consideration of the kinds of“overaccommodations” and “underaccommodations” that can affect interaction. Theseoften occur when one communication partner has a “stereotypical” view of another. Forexample, overaccommodations abound inresidential facilities, as exemplified when staffuse a higher pitch and volume, exaggeratedintonation, simplified grammatical structuresand vocabulary, greater repetition and termsof endearment (honey, lovey) with theirelderly residents or with adults with disabilities (Worrall & Hickson, 2007). An exampleof an underaccommodation is the situation inwhich a communication partner fails to recognize the signals of another or lacks awarenessof cross-cultural issues.In addition, our interactions have changeddramatically over the past few decades, reflecting advances in information and communication technologies. An increasingly highpercentage of human interaction today doesnot occur face-to-face, but rather asynchronously and across great distances, using text,graphics, photos, avatars, sounds, and othermedia, as well as spoken language.The theoretical construct of communication we use in this book is groundedin cognitive science and psycholinguistics,widely supported by research, and links easily to other theoretical constructs that addresshuman interaction and language (Clark,

Issues and Challenges in Advancing Effective Patient-Provider Communication 112005; Goodwin, 2003; Hutchins, 2001). Wedefine communication as the joint establishment of meaning, wherein meaning is jointlyestablished or coconstructed using a varietyof strategies, which include the simultaneoususe of common modalities (speech, gestures,manual signs, facial expressions, electronicand nonelectronic technologies, etc.) (Blackstone, Wilkins, & Williams, 2007).The Joint Commission, a health-careaccrediting agency in the United States,recently adopted this definition of communication in its standard for hospitals, AdvancingEffective Communication, Cultural Competence, and Patient- and Family-Centered Care:A Road Map for Hospitals (The Joint Commission, 2010), applying it specifically to interactions between patients and providers:toward that goal usually requires that patientand provider be able to communicate effectively. Medical encounters are often highstakes interactions and may be stressful andtime constrained. Thus, although successful communication is a critical componentof each encounter, it can be very difficult toachieve for a myriad of reasons. For example,interactions between patients and providersoften involve individuals who are not familiar with one another, may have very differentviews about the world, and even speak different languages. Patients (or providers) mayhave difficulty hearing, speaking, understanding, or remembering what is being said. Family members may be present, and when theyare, can influence patient-provider communication, making it easier or, in some cases, moredifficult. Also, interactants may be distractedby concerns that have absolutely nothing toEffective communication is the successfuljoint establishment of meaning whereindo with the situation at hand, such as worpatients and health care providers exchangerying about a sick child left at home, whatinformation, enabling patients to particito make for dinner, or an argument with apate actively in their care from admissionspouse. Finally, many significant issues arethrough discharge, and ensuring that thetoo rarely acknowledged or understood,responsibilities of both patients and proincluding socioeconomic issues, educationalviders are understood. To be truly effecbackground, culture and religion, race, ethtive, communication requires a two-waynicity, sexual orientation, gender identity, ageprocess (expressive and receptive) in whichand other personal characteristics or beliefs.messages are negotiated until the informaSome of these can function as “the elephant intion is correctly understood by both parties.the room.”Successful communication takes place onlyAs LaPointe (1996) pointed out, healthwhen providers understand and integratethe information gleaned from patients, andcare professionals need to guard against thewhen patients comprehend accurate, timely,routineness of their procedures and practices.complete, and unambiguous messages fromReflecting on his own experience as a patient,providers in a way that enables them to parLaPointe recalls a nurse who greeted him forticipate responsibly in their care. (The Jointa scheduled medical procedure saying, “SoCommission, 2010, p.1)you’re the cysto.” He writes, “I’m a bit morethan ‘the cysto.’ I am a person that is scared atthe moment and worried about my future anda bit more complex than a shorthand nameCommunication Challengesfor a medical procedure” (LaPointe, 2011).During Medical EncountersHe reminds providers of the need to explainprocedures in a way that the patient canPatients and providers share a common goal — understand, to reveal and clarify rationales, tothe patient’s health; however, making progress answer questions, and to calm fears. Providers

12 Patient-Provider Communicationshould find ways for patients to express theirconcerns, describe their symptoms, talk aboutwhat might be bothering them, ask questions,and get their needs met. This information isessential to receiving an accurate diagnosis,appropriate treatment, and adequate followup, and experiencing better health. One available model is Dr. Arthur Kleinman’s NineQuestions, a clinical tool designed to bring outa patient’s health beliefs (U.S. Department ofHealth and Human Services Office of Minority Health, 2014). In short, to preserve theindividuality and dignity of each person anddo their jobs well and in a timely fashion, providers need to have the communication skillsrequired to treat all their patients, includingthose with communication challenges.Kleinman’s Questions (adapted from APhysician’s Practical Guide to CulturallyCompetent Care. Available at: https://cccm .thinkculturalhealth .hhs.gov/):1. What do you call your problem?What name does it have?2. What do you think caused yourproblem?3. Why do you think it started when itdid?4. What does your sickness do to you?How does it work?5. How severe is it? Will it have a shortor long course?6. What do you fear most about yourdisorder?7. What are the chief problems thatyour sickness has caused for you?8. What kind of treatment do you thinkyou should receive?9. What are the most important resultsyou hope to receive from the treatment?Breakdowns in health care communication can occur at any time (during regis-tration, at an office visit, at discharge, in atherapy session, before or after surgery), inany place (doctor’s office, emergency room,hospital, skilled nursing facility), and be experienced by anyone (patients, family members,health care providers, other workers). No oneis immune. In fact, it is quite surprising that somany medical encounters are successful, andthat even when problems occur, most communication partners find ways to circumventbarriers by making adjustments to their ownbehavior, or by managing to negotiate a solution with their communication partner. Forexample, interactants may vary the modes ofcommunication they use, decide to changetheir position (e.g., sit down or stand up),modify their nonverbal or verbal behaviors,rephrase the content of their message, or altersome aspect of the environment. A nurse whoobserves an agitated patient who is intubatedmay present the patient with a communication display and say, “Please show me what’swrong.” A speech-language pathologist whoneeds to talk with a patient with limited English proficiency about a swallowing assessmentand treatment options may request a medicalinterpreter.Most professional training programs recognize the importance of teaching studentseffective communication skills, and while theamount of time directed to communicationtraining in medical and allied health educational programs is often quite limited, mostprofessionals are well aware of issues that causecommunication breakdowns. For example,professional preparation programs teach general information, such as the importance ofspeaking with patients and families in a respectful manner, using “plain language,” reducingrate of speech, and listening closely. Manyprofessionals also learn to use evidence-basedtechniques, such as teach-back, a strategy thataims to help ensure patients have understoodcritical information (Dinh, Clark, Bonner, &Hines, 2013; Jager & Wynia, 2012). More

Issues and Challenges in Advancing Effective Patient-Provider Communication 13specific information about medical educationprograms is featured in Chapter 3.Communication VulnerablePopulations“Vulnerable” is a term used to refer to groupsthat are at high risk. Health care, emergencymanagement, education, economics, sociology, and psychology often describe “vulnerable populations” as groups that are at increasedrisk because of poverty, health disparities, disabilities, limited health literacy, incarceration,limited social networks, and so on. Vulnerability is not only related to something inherent to an individual, but in fact, far moreoften reflects barriers people experience whendenied access to social and material resources(Miller et al., 2010).We define “communication vulnerability” as the diminished capacity of an individualto speak, hear, understand, read, remember, orwrite due to factors that areinherent to the individual (e.g.,disabilities related to receptive andexpressive language skills, hearing,vision, speech, cognition, memory,as well as language spoken, lifestyle,belief system, etc.) orn related to the context or situation (e.g., a noisy environment,being intubated in an intensivecare unit after surgery, sufferinginjury while traveling in a foreigncountry, having cultural practices,lifestyles, or religious beliefs thatare not understood or accepted byproviders).nEarlier definitions of communicationvulnerability tended to omit entire groupsof people and ignore or de-emphasize factors external to the patient. For example, theEthical Force Program Consensus Report(American Medical Association, 2006) statedthat communication vulnerable populationsare those “whose members have limited or noEnglish proficiency, a culture that is not wellunderstood by personnel in the organization,and/or limited health literacy skills” (p. 9).This definition does not include people withcommunication disabilities. Costello, Patak,and Pritchard (2010) aimed to correct thisoversight by defining communication vulnerable individuals as having “diminishedcapacity in expressive and/or receptive communication abilities” (pp. 289–290), whichinadvertently overlooks factors external to theindividual. The Joint Commission’s (2010)definition of communication quoted earliercorrects these narrower interpretations.We identify five patient groups as “communication vulnerable” in Figure 2–1.People With Disabilities AffectingCommunication (Speaking, Hearing,Seeing, Understanding, Reading,Remembering, and Writing)Nearly one in five people in the UnitedStates has a disability (U.S. Census Bureau,2012). A substantial number of individuals have communication disabilities (American Speech-Language-Hearing Association,2011). Approximately 27 million people havedifficulty hearing or are deaf (Berke, 2010;American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, 2008a, 2010a). As many as 46 millionadults and children have some type of disorderthat affects their ability to speak and/or understand language (American Speech-LanguageHearing Association, 2008a, 2008b, 2010a;National Institute on Deafness and OtherCommunication Disorders, 2011; U.S. Department of Education, 2006). Recently, Collier and colleagues (2012) surveyed adults withcommunication disabilities and their disabilityservice providers in Canada to identify areas

pitals, rehabilitation hospitals, nursing homes, long-term care facilities, and hospice settings. Examples of communication support materi- . Madonna Rehabilitation Specialty Hospital, Bellevue, Nebraska Wendy Walsh, Homeland Defense & Security Coordinator, Naval Postgraduate School, Monterey, California Carrie Windhorst, SLP, Long-term Acute .