Transcription

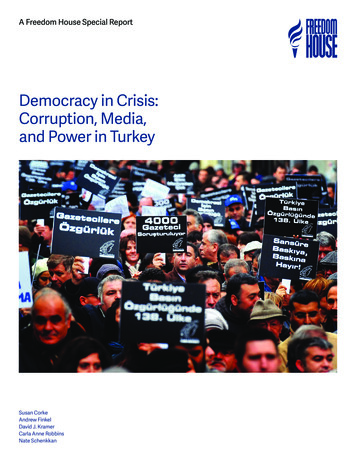

A Freedom House Special ReportDemocracy in Crisis:Corruption, Media,and Power in TurkeySusan CorkeAndrew FinkelDavid J. KramerCarla Anne RobbinsNate Schenkkan

Executive Summary1IntroductionThe Media Sector in TurkeyHistorical Development355The Media in CrisisHow a History Magazine Fell Victimto Self-Censorship810Media Ownership and DependencyImprisonment and ean UnionUnited States16161717Cover: Mustafa OzerAFP / GettyImagesAbout the AuthorsSusan Corke isdirector for Eurasiaprograms at FreedomHouse. Ms. Corkespent seven years atthe State Department,including as DeputyDirector for EuropeanAffairs in the Bureauof Democracy, HumanRights, and Labor.Andrew Finkelis a journalist basedin Turkey since 1989,contributing regularlyto The Daily Telegraph,The Times, TheEconomist, TIME,and CNN. He has alsowritten for Sabah,Milliyet, and Taraf andappears frequently onTurkish television. Heis a founding memberof P24, a Turkish NGOwhose purpose is tostrengthen the integrityof independent mediain Turkey.David J. Krameris president of FreedomHouse. Prior to joiningFreedom House in2010, he was a SeniorTransatlantic Fellow atthe German MarshallFund of the United States.Mr. Kramer served asAssistant Secretary ofState for Democracy,Human Rights, andLabor from March 2008to January 2009 and wasalso a Deputy AssistantSecretary of Statefor European andEurasian Affairs.Carla Anne Robbinsis clinical professorof national securitystudies at BaruchCollege/CUNY’s Schoolof Public Affairs andan adjunct seniorfellow at the Councilon Foreign Relations.She was deputy editorialpage editor atThe New York Timesand chief diplomaticcorrespondent at TheWall Street Journal.AcknowledgmentsIn researching this report Freedom House spoke with more than two dozen journalists and editors,as well as think tank representatives, civil society activists, and high-ranking Turkish governmentofficials. We thank all of those who agreed to speak with us for their honesty and directness.Special thanks to Robert Ruby, Senior Manager for Communications for Freedom House.Nate Schenkkanis a program officerat Freedom House,covering CentralAsia and Turkey.He previously workedas a journalistin Kazakhstan andKyrgyzstan andstudied at AnkaraUniversity as a CriticalLanguages Fellow.

Freedom HouseExecutive SummaryIn November 2013, a Freedom House delegation traveled to Turkey to meet withjournalists, NGOs, business leaders, and senior government officials about thedeteriorating state of media freedom in the country. The delegation’s objectivewas to investigate reports of government efforts to pressure and intimidate journalists and of overly close relationships between media owners and government,which, along with bad laws and overly aggressive prosecutors, have muzzledobjective reporting in Turkey.Since November, events in Turkey have taken a severeturn for the worse. The police raids that revealed acorruption scandal on December 17, and the allegations of massive bidrigging and money laundering bypeople at the highest levels of the government, havesparked a frantic crackdown by the ruling Justice andDevelopment (AK) Party. More journalists have beenfired for speaking out. Thousands of police officersand prosecutors have been fired or relocated acrossthe country. Amendments to the Internet regulationlaw proposed by the government would make itpossible for officials to block websites withoutcourt orders. The government is also threatening theseparation of powers by putting the judiciary, including criminal investigations, under direct control of theMinistry of Justice. The crisis of democracy in Turkeyis not a future problem—it is right here, right now.This report on the media recognizes that what ishappening in Turkey is bigger than one institution andpart of a long history that continues to shape currentevents. The media in Turkey have always been closewww.freedomhouse.orgto the state; as recently as 1997, large media organizations were co-opted by the military to subvert ademocratically elected government. The AK Party wasformed in the wake of those events. But even as it hastamed the military, the AKP has been unable to resistthe temptations of authoritarianism embedded in thestate. Over the past seven years, the government hasincreasingly employed a variety of strong-arm tacticsto suppress the media’s proper role as a check onpower. Some of the most disturbing efforts includethe following: Intimidation: Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğanfrequently attacks journalists by name after theywrite critical commentary. In several well-knowncases, like those of Hasan Cemal and Nuray Mert,journalists have lost their jobs after these publicattacks. Sympathetic courts hand out convictionsin defamation cases for criticism. Mass firings: At least 59 journalists were firedor forced out in retaliation for their coverage of1

SPECIAL REPORTDemocracy in Crisis: Corruption, Media, and Power in Turkeylast summer’s Gezi Park protests. The Decembercorruption scandal has produced another stringof firings of prominent columnists. Buying off or forcing out media moguls:Holding companies sympathetic to the governmentreceive billions of dollars in government contracts,often through government bodies housed in theprime minister’s office. Companies with mediaoutlets critical of the government have beentargets of tax investigations, forced to pay largefines, and likely disadvantaged in public tenders. Wiretapping: The National Security Organizationhas wiretapped journalists covering nationalsecurity stories, using false names on the warrantsin order to avoid judicial scrutiny. Imprisonment: Dozens of journalists remainimprisoned under broadly defined antiterrorismlaws. A majority of those in prison are Kurds, andsome analysts believe the government is usingthem as bargaining chips in negotiations withthe Kurdish PKK.These tactics are unacceptable in a democracy. Theydeny Turkish citizens full access to information andconstrain a healthy political debate. Journalists andgovernment officials alike acknowledge that reportersand news organizations have practiced self-censorship to avoid angering the government, and especiallyPrime Minister Erdoğan.The intentional weakening of Turkey’s democraticinstitutions, including attempts to bully and censorTurkey’s media, should and must be a matter of deepconcern for the United States and the EuropeanUnion. As the AK Party’s internal coalition has grownmore fragile, Erdoğan has used his leverage over themedia to push issues of public morality and religionand to squelch public debate of the accountability ofhis government. The result is an increasingly polarizedpolitical arena and society.2Freedom House calls on the government of Turkeyto recognize that in a democracy, a free press andother independent institutions play a very importantrole. There are clear and concrete steps the Turkishgovernment must take to end the intimidation andcorruption of Turkey’s media. Chief among these arethe following: Cease threats against journalists. Repeal the criminal defamation law and overlybroad antiterrorism and “criminal organization” lawsthat have been used to jail dozens of journalists. Comply with European and international standardsin procurement practices in order to reducethe incentive for media owners to curry favorby distorting the news. Turkish media ownersthemselves must make a commitment to supportchanges in procurement practices if they are towin back the trust of Turkey’s citizens.Although building a resilient democracy is fundamentally up to Turkish citizens, the international community cannot afford to be bystanders. The EuropeanUnion and the OSCE have raised strong concernsabout government pressure on Turkey’s media, andthe EU’s warnings against governmental overreachhave been pointed. Unfortunately, the same cannot besaid for the United States. The Obama administrationhas been far too slow to realize the seriousness of thethreat to Turkey’s democracy. U.S. criticism of theTurkish government’s recent actions has come fromthe State Department spokesperson and White Housepress secretary, not from the high-ranking officialswho need to be engaged in responding to a crisis ofthis scale. Where European governments and institutions have been specifically and publicly engaged withthe government over the crisis, the Obama administration has avoided the difficult issues. It is time tospeak frankly and with seriousness about the growingthreat to democracy in Turkey, and to place freedomof expression and democracy at the center of thepolicy relationship.

Freedom HouseIntroductionTurkey’s democracy is in crisis. Three and a half millionpeople across the country took part in the Gezi Parkprotests last summer. Yet the AKP-led government’sresponse, first to the protests and now to theDecember 17 corruption scandal, has been to crackdown even harder on its critics, fanning even widerpublic alienation. At least 59 journalists were firedduring the Gezi protests for criticism of the government, and more have lost their jobs in recent weeksfor criticizing the government over corruption. Asthis report is being written, Prime Minister Erdoğanis advocating the reversal of important democraticreforms his own party championed just a few years ago.This report focuses on one element of the crisis inTurkey’s democracy: the government’s increasingpressure on the media over the last seven years.While acknowledging that Turkey’s current crisis isbigger and more systemic, Freedom House believesit is important to analyze in depth the government’sefforts to marginalize and suppress independentvoices and reporting in Turkey’s media. A free press isa vital actor in any democracy, providing accountabilityand encouraging a healthy public debate. In Turkey,with a weak opposition and judiciary, an unfetteredpress is essential. The muzzling of the press in the lastseven years has contributed to the wide disjuncturebetween citizens and their government. It is both asymptom and a cause of the current crisis.The problem of media freedom—and the eagercollaboration by media owners with the government—did not start with the AK Party. During nearly fivedecades of military “guardianship” (punctuated bycoups in 1960, 1971, and 1980), the Turkish militaryand their bureaucratic allies enforced a set of red lineswww.freedomhouse.orgrestraining discussion of ethnic identity, religion,and history outside the narrow bounds of secularnationalism. In 1997, leading media outlets supportedthe military’s efforts to undermine the coalition led bythe Islamist Welfare Party, which eventually led to thecollapse of the democratically elected governmentin what is often called the “post-modern coup.”Formed after the banning of the Welfare Party andits successor, the Virtue Party, the AK Party was avictim of these harsh restrictions on free speech.Then-mayor of Istanbul Recep Tayyip Erdoğanserved jail time after he gave an Islamic-nationalistspeech in 1997, and was still banned from serving inoffice when his AKP won general elections in 2002.Although the party arguably won on the public’smistrust of a political establishment that had drivenit into economic crisis in 2001, the AKP’s commitmentto inclusive, democratic governance also appealedto Turkey’s voters and clearly distinguished it fromthe Welfare Party.Many in Turkey, including liberals and members ofminority groups interviewed for this report, agreethat there was progress under the AK Party in someimportant areas of free expression. Long-standingtaboos against discussion of minority rights, includingthe rights of Kurds and Alevis, headscarves for women,and the Armenian genocide have all been lifted, evenif laws that could punish such discussion remain onthe books. Given the severe restrictions under militarytutelage, these accomplishments are not insignificant.Yet credit for such gains cannot offset the atmosphereof intimidation that deepened as the AKP consolidatedits power. Kurdish journalists have been arrested3

SPECIAL REPORTDemocracy in Crisis: Corruption, Media, and Power in Turkeyalong with Kurdish activists and held as bargainingchips in peace negotiations with the KurdistanWorkers’ Party (PKK). Editors and reporters fromacross Turkey’s media told Freedom Houseabout angry phone calls from the prime minister’soffice after critical stories run, and—long beforeGezi—of media owners being told to fire specificreporters. In a growing number of cases, editors andowners are firing reporters preemptively to avoid aconfrontation with government officials. Reporterswho still hold their jobs admit to censoring their owncoverage to ensure they remain employed. When theycover politics, media employees are forced to be moreconcerned about their jobs than about the story.At the heart of the problem are politicians and aprime minister who came to power vowing to createa more liberal government but have become increasingly intolerant of criticism and dissent. Even aslate as 2010, the AK Party successfully campaignedto pass a referendum allowing the parliament toamend aspects of the 1982 constitution, adoptedwhile Turkey was under martial law. The referendumincluded numerous changes to increase the independence of the judiciary, to improve separation ofpowers, and to protect the rights of individuals.Following its victory in 2011, the AKP pledged towork with other parties to rewrite the constitutionaltogether, a project that has now collapsed.Yet despite winning the referendum and holding aparliamentary majority, the AKP has not rejected thearbitrary powers the state still retains, or built a strongsystem of democratic checks and balances. Amongthe changes proposed by the party after the corruption scandal broke this December has been a repealof the democratic reforms to the judiciary it fought forin 2010. Limited improvements in media laws havebeen trumped by the government’s continued useof broad antiterrorism and criminal defamation lawsthat allow the government wide leeway in punishingdissent. The government has also not hesitated to usean intrusive state security apparatus to illegally spyon and harass journalists.The government’s greatest leverage over themedia, however, is economic. The prime minister’soffice controls the allocation of billions of dollarsin privatized assets, housing contracts, and a publicprocurement process that allows rewarding favoredcompanies, including those with media arms. As theAK Party has consolidated power, it has used thegovernment agency responsible for sales of defaultingcompanies to transfer control of some of thecountry’s most important media outlets to supporters.Tax investigations have been used to punish mediaoutlets that dare to challenge the government. Theonce-dominant Doğan Media Group was assessedenormous fines and forced to sell off several mediaproperties, including one of the country’s leadingpapers, Milliyet, after its reporting on AKP corruptioninfuriated the government.Now, as the December 17 corruption scandalunfolds, the retreat from the early years of the AKP-ledliberalization is in full force. The government has evenfloated the possibility of mending its bridges with themilitary, claiming that it was the same over-zealousprosecutors from the Gülen religious community whoinitiated the coup-conspiracy trials that broke themilitary’s influence. All of this has led to a profoundcrisis of confidence in the Erdoğan government and,chillingly, the future of Turkey’s democracy.There are positive signs that with the governmentsuddenly weakened, some of Turkey’s media arebeginning to remember their long-suppressed role,breaking stories and covering the corruptionscandal in depth. Outlets associated with theGülen movement like Zaman, Today’s Zaman, andBugün; Doğan-owned Radikal and Hürriyet; T24, anindependent Internet news site;1 and even formerlypro-government media like Habertürk are findingtheir voices after years of harassment and pressure.There is no way of knowing how long or even whetherthis will last. At the same time, yet more prominentcolumnists are losing their jobs, such as Nazlı Ilıcakfrom Sabah and Murat Aksoy from Yeni Şafak.As reflected in Freedom House’s annual ratings,including Freedom in the World, Turkey is not adictatorship. It is a country where different views areexpressed and heard, with a vibrant and diverse civilsociety. But it remains a country where criticizingthe government means risking your livelihood, yourreputation, and sometimes, your freedom. And at thepresent moment, it is a country where the government is behaving more, rather than less, authoritarian.The European Union and the United States must befully engaged in the defense of Turkey’s democracy.While the EU has spoken out forcefully in recent1 Disclosure: The owner of T24 Doğan Akın is a founding member of P24, a non-profit organization that promotes press independence,of which report co-author Andrew Finkel is also a founding member.4

Freedom Housemonths as Turkey has moved further away from itsdemocratic commitments, the U.S. has refrained fromhigh-level criticism or engagement. It is past the timefor a real change in U.S. policy to one based onhardheaded analysis.There are long-term steps that the U.S. should supportto encourage reform in Turkey, including negotiating afree-trade pact to parallel the Transatlantic Trade andInvestment Partnership between the U.S. and EU.Such an agreement must require that Turkey committo transparent procurement practices. In additionto strong rhetorical defenses of a free Turkish press,the United States and Europe should also marshalinvestment and development funds to support thegrowth of independent Turkish media. Most important,with Turkey’s government proposing new steps everyday that would reverse democratic gains, the U.S.should elevate Turkey’s democratic crisis to a matterof bilateral importance and engagement. The crisis isreal and Turkey is too important in its own right, and inits relations with other countries, for more denial ordeliberate inattention.The Media Sector in TurkeyEven with the constraints placed on a free press,Turkey has a rapidly growing media and entertainmentsector—the result of the increasing education andwealth of a population with a deep hunger forinformation about their country and the world. In2013, PricewaterhouseCoopers projected the sector’svalue at 11.6 billion, with estimated 11.4 percentannual growth between 2013 and 2017, more thandouble the global average.1 Among European countries, Turkey has a relatively low newspaper circulationof 96 newspapers bought daily per 1,000 population.2Spurred by the growth in the Turkish economy,advertising revenue reached 2.5 billion in 2011, thebulk of which accrued to television, which includespopular serials, sports, and daytime talk shows, aswell as news coverage.3 A small number of wealthyholding companies own nearly all of the country’smost important outlets in both television and print.Many companies are dependent on government favor,and even those with limited direct dealings with thegovernment would find it hard to operate in the faceof active hostility.National newspapers based in Istanbul and Ankaraaccount for 80.6 percent of the country’s annualcirculation,4 and at most a dozen of those dominatethe national conversation on domestic politics andwww.freedomhouse.orginternational affairs.5 Most media outlets havewell-known and clear-cut political allegiances. Sözcü(360,000 circulation) is Kemalist, BirGün (11,000) isleftist, Yeni Şafak (127,000) is Islamist, Zaman(1,161,000) is associated with the Gülen movement,and so on.6 The ideological profiles of the papers canmask the depth of the harassment and restrictions onTurkey’s media. In interviews for this report, high-ranking officials repeatedly pointed to the polemicalantigovernment tone of Sözcü, for instance, as proofof freedom of speech. But despite being among thecountry’s highest-circulating dailies, Sözcü onlyreaches the substantial minority already predisposedto its secularist Kemalist views, which would nevervote for the AK Party. It is not a government target.There is also a group of newspapers considered“mainstream,” meaning that despite their politicallegacies they can reach an audience beyond thetrue believers of one ideological group. These papersinclude Hürriyet (409,000), Milliyet (168,000),Sabah (319,000), and Akşam (103,000). A key aspectof the government’s efforts to control the media hasbeen to focus most of its attention and pressure onthese “mainstream” outlets. The government-backedsales of Sabah and Akşam to pro-governmentbusiness groups and the forced sale of Milliyet to apro-government business group to pay off the DoğanMedia Group’s tax penalties reduced these papers’independence. Milliyet has laid off important criticalcolumnists like Hasan Cemal and Can Dündar.In the most flagrant cases of Sabah and Akşam,the papers have become mouthpieces for thegovernment, what some call “Erdoğanist” media.Historical DevelopmentThe events of the last 12 years, including the AKPled government’s intensifying crackdown on mediafreedom, cannot be understood without the contextof decades of military “guardianship” and the overlyclose relationship between the military and the media.While ownership has shifted, in many cases the desireto curry favor with the government has remained thesame. Following the coup of 1980 and the development of liberal economic policies under then-PrimeMinister Turgut Özal, family ownership in the mediamarket was replaced by corporate holding companies (albeit still with a strong family component) thatbenefited hugely from their close relationships withthe government.5

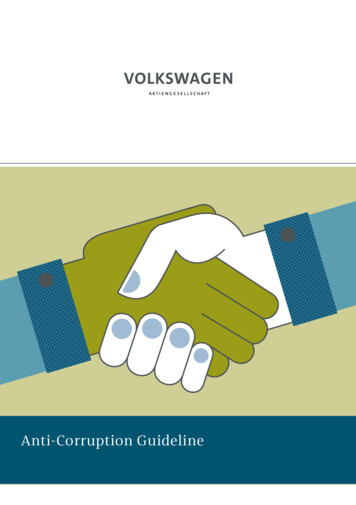

SPECIAL REPORTDemocracy in Crisis: Corruption, Media, and Power in TurkeyIn nearly all cases, these holding companies earnonly a small fraction of their revenue from their mediaoutlets, with the bulk of profits coming from otherinterests, such as construction, mining, finance, orenergy (see Table 1). In Turkey’s still state-centeredeconomy, privatization of government assets andgovernment contracts are a huge source of theholding companies’ income. This has created asituation in which media outlets are used to promotethe ownership group’s financial interests. Membersof the media and the government alike describenewspapers’ Ankara bureau chiefs as “lobbyists” fortheir companies.7Table 1.Main ownershipgroups in Turkey’smedia, January 2014Even as Erdoğan and Gül distanced themselves fromthe more aggressive Islamism of the Welfare Party,they still carried a profound sense of vulnerabilityand victimhood.When the AK Party came to power in 2002, it borethe scars of those experiences. Erdoğan, now leader ofthe AKP, was only allowed to assume the premiershipafter a constitutional amendment in 2003. Five yearslater, the AKP faced another serious challenge to itsexistence when the Constitutional Court came onlyone vote short of ruling that the party should beclosed for violating the constitution’s commitmentto secularism.Holding company owners who rely on the state forbusiness have shown little commitment to realdebate, and even less sense of responsibility forproviding a check on government power. In 1997,when the military forced the collapse of a coalitionled by the Islamist Welfare Party, large mediaoutlets supported the military with sensationalizedand baseless stories about the Islamist threatto democracy.8From its inception, the AK Party presented a verydifferent image to that of its more Islamic predecessor.It committed to a greater openness for religion inpublic life in the context of its program to make Turkeymore fully democratic. It actively embraced the freemarket, rejected anti-Western rhetoric, and pledged toimplement an IMF standby agreement that requireddifficult economic reforms.The AK Party and the current government were forgedby that history. Prime Minister Erdoğan and PresidentAbdullah Gül were both members of the bannedWelfare Party. When Erdoğan served four months inprison in 1997, and was subsequently barred fromholding public office, the secularist media applauded.9The AK Party’s decision to pursue European Unionaccession required additional reforms and won newsupport from the international community, originallywary of the party’s Islamic roots. The aftereffectsof the currency devaluation in 2001 and the IMF’sbacking helped attract foreign investment, and theOwnership GroupNewspapersTVOther Business InterestsDoğan GroupHürriyet, Radikal, PostaCNNTürk, Kanal DEnergy, retail, industry, tourismDoğuş Group--NTV, StarFinance, Automotive, Construction,Energy, RetailFeza Media GroupZaman, Today’s ZamanEthem SancakAkşamSkyTurk 360PharmaceuticalsStar Media GroupStarKanal 24Energy (50 percent owned by theState Oil Company of Azerbaijan)Kalyon GroupSabah, TakvimATVConstructionCiner GroupHabertürkShow TV, Habertürk TVEnergy, Mining, ServicesDemirören GroupMilliyet, Vatan--Energy, Mining, Industry,Construction, Tourismİhlas HoldingTürkiyeTGRT HaberConstruction, Industry, Tourism,MiningAlbayrak GroupYeni ŞafakTVNETConstruction, Industry, Logistics,Energy, ServicesKoza İpek HoldingBugünKanaltürkMining6Not available

Freedom Housenew macroeconomic stability created a windfall oflower interest rates and a decline in Turkey’s chronically high rate of inflation. This allowed the AKP todirect resources to its constituents in neglected citiesacross the country and to provide opportunities forthe new business class. The EU’s strict demands forinstitutional reform provided an additional mandatefor decreasing the involvement of the military inpublic life and gave an opportunity to install new (and,in some cases, more professional) cadres in the civilservice, police, and judiciary.In its fight against the old guard, the AK Party alsocreated a wider space for ideas and discussion. Yet asthe AKP strengthened its political position, it began toassert more control over the media sector, and the oldred lines were replaced with new ones. An importantstep came in 2007 when the country’s second-largestmedia group, Sabah-ATV, was sold to Çalık Holding.Prime Minister Erdoğan’s son-in-law Berat Albayrakwas the company’s CEO, and Albayrak’s brother ledthe media unit.10 In an unusual move, two state banksstepped in with financing worth 750 million of the 1.1 billion purchase.11 Sabah’s editorial line rapidlyshifted from center-left to ardently pro-government.12That same year, the government took aim at thelargest media owner in the country, Doğan MediaGroup, which had long been associated with thesecularist elite and had backed the 1997 “post-modern coup.” Doğan had enraged PM Erdoğan when itsflagship papers, Hürriyet and Milliyet, gave extensivefront-page coverage of a German court case, accusingseveral prominent Turkish citizens with ties to the topof the AKP of embezzling tens of millions of dollarsfrom a Turkish charity.Erdoğan responded by calling for a boycott of theentire media group.13 In February 2009, Doğan MediaGroup was hit with a 500 million tax fine, raised inSeptember of the same year to 2.5 billion, four-fifthsof the market capitalization of the entire company.14The fine eventually forced Doğan to reduce itscommanding position in the Turkish press, includingby selling Milliyet and Vatan to another holdingcompany with strong ties to the government.The AKP also took on the military in 2007. In April, thearmy issued a statement pledging to be an “absolutedefender of secularism” in a veiled threat reminiscentof 1997.15 In June, police launched the raids thatwould lead to accusations against ten army generalsand hundreds of other officers, as well as variouswww.freedomhouse.orgjournalists and professors, for seeking to underminethe government with a convoluted conspiracy—known as Ergenekon, after a mythical place of originof the Turkish people—of assassinations and false flagoperations. The indictments and trials were markedby appalling breaches of due process and judicialprocedure, years of pretrial detention, and simplelogical incoherence.Nevertheless, Ergenekon ended in September 2013with the conviction of 275 defendants, includingthe former chief of the Armed Forces. With militarytutelage finally broken and the political oppositionstill tainted by its association with the military, the AKParty became the dominant political force in Turkey.The AKP did not break the old media or militarytutelage by itself. Until recently, one of its key allieswas the Gülen movement, a tightly networked groupfollowing the teachings of Islamic preacher FethullahGülen. The movement wields enormous economicand social power with a network of hundreds ofschools and colleges in Turkey and abroad, andextensive business interests inside and outside thecountry. Turkey’s highest-circulation daily Zaman andthe influential English-language Today’s Zaman areowned by the Gülen-affiliated Feza Media Group. Kozaİpek Holding, which owns Bugün daily and KanaltürkTV station, is also affiliated with the movement.When Doğan Media Group was under attack, Gülenistoutlets were vocal in defending Erdoğan and blamingthe group’s owner Aydın Doğan for bringing the primeminister’s wrath upon himself.16 During the Ergenekoncases, prosecutors allied with Gülen were seen asdriving the charges against the military through leaksand stories in the movement’s outlets and to sympathetic journalists.The alliance between Gülen supporters and Erdoğanstarted to change as the government took a moreconfrontational stance towards Israel and pursuedrapprochement with the Kurdish PKK, which theGülen movement has opposed for decades.17A failedattempt to remove Turkey’s intelligence chief HakanFidan in February 2012 was widely attributed to Gülensupporters within the judiciary unhappy with theoutreach to PKK leader Abdullah Öcalan.18 The splitbetween Gülen supporters and Erdoğan has nowburst into full public view with the December 17corruption scan

and Power in Turkey. Executive Summary 1 Introduction 3 The Media Sector in Turkey 5 Historical Development 5 The Media in Crisis 8 . response, first to the protests and now to the December 17 corruption scandal, has been to crack down even harder on its critics, fanning even wider public alienation. At least 59 journalists were fired