Transcription

PHASING OUT PETROL AND DIESEL CARS& VANS FROM THE PUBLIC SECTOR FLEETMEETING THE ELECTRIC VEHICLEINFRASTRUCTURE CHALLENGEAPRIL 2022

ContentsSummary21SFT and Net Zero Transport32Policy Background43Purpose of this Report54Progress in Phasing Out Cars & Vansfrom Public Sector Fleet65Barriers in Meeting the Investment Challenge76Opportunities for Delivery86.187Overview6.2 Shared Learning Forums &Knowledge Hubs86.3 Shared Resources & Joint Working96.4 Optimising the Infrastructure Costs96.5 Operating Networks10Funding & Financing Options117.1Background117.2Leveraging Local Authorities’Borrowing Capacity117.3UK Infrastructure Bank117.4Community Municipal Investments117.5Leasing127.6Supplier Finance137.7Reducing the Cost of Finance138Other Partnership Models149Procuring Charging Infrastructure1510Potential Next Steps1611Acknowledgements17Meeting the electric vehicle infrastructure challenge 1

SummaryThe Scottish Government made thecommitment to“work with public bodies tophase out petrol and diesel carsfrom our public sector fleet andphase out the need for any newpetrol and diesel lightcommercial vehicles by 2025”.Whilst good progress has been made, supply chainpressures, inflation and extended lead times reinforcethe need to move at pace on decarbonising publicsector cars and vans and procuring charginginfrastructure.As the benefits of zero emission vehicles are expectedto increase, Transport Scotland has signalled thatfuture funding is likely to focus on higher cost specialistvehicles and their charging infrastructure. Public bodieswill therefore need to consider new ways to financecharging infrastructure to support the decarbonisationof their car and van fleets.Transitioning to zero emission vehicles presents anopportunity to assess the role of cars and vans in thepublic sector fleet, to rationalise fleets and contributeto the target of reducing car kms travelled by 20%.Collaboration between public bodies and with theprivate sector on charging infrastructure, can helpmake best use of resources, optimise investments,reduce costs, maximise benefits and reduce therequirement for funding.Many of the Region and City growth deals identifiedlow carbon initiatives as a priority. There may besynergies with these initiatives and expanding fleetcharging infrastructure.Future bids to the UK Government’s Levelling Up fundmay also present opportunities to secure funding forfleet infrastructure.For some local authorities, the most practical financingoption may be the Public Works Loan Board.There is potential for local authorities to partner withother public bodies who do not have borrowing powersand for local authorities to procure charginginfrastructure services on their behalf.For EV infrastructure initiatives at scale, the UKInfrastructure Bank is another potential source offinance for local authorities.Community Municipal Investments is an alternativeoption which has been adopted by a small number oflocal authorities in England Wales for local carbonreduction initiatives.Shared learning, providing greater visibility of futureinfrastructure plans and joint working could helpaggregate demand and accelerate delivery.Lease finance is widely available for both vehicles andinfrastructure. Other supplier finance models such as“Charging-as-a-Service” are beginning to emerge.It is important to assess what investment is required.Shared chargepoints and extending homebasedchargepoint installations can reduce costs andincrease productivity.Where the preference is to adopt private finance,creating the conditions to attract private capital to thissector will be important such as being clear on theincome stream to be generated. If there is short termuncertainty around this, a minimum level of utilisationguarantee could be considered.Public bodies should consider if a centralised publicchargepoint management system will deliver the bestresults for their fleet. Chargepoint interoperability toenable future shared access to chargepoints will be animportant consideration going forward.There are many routes to market through which privatefinance could be mobilised. In a developing market,pre-procurement planning, and early supplerengagement are essential to help deliver successfuloutcomes.Meeting the electric vehicle infrastructure challenge 2

1.SFT and Net Zero TransportSFT was established by Scottish Government as acentre of infrastructure expertise. We provide additionalskills, resource and knowledge to public sectororganisations, supporting them plan, fund, deliver andmanage their infrastructure projects and programmes.SFT is working closely with Transport Scotland andpublic bodies across Scotland to help accelerate thedelivery of an expanded public EV charging networkand the delivery of public sector fleet charginginfrastructure. SFT is also supporting TransportScotland on the delivery of their Zero Emission BusChallenge Fund (ScotZEB).Meeting the electric vehicle infrastructure challenge 3

2.Policy BackgroundScottish Ministers have set ambitious climate targets,with a statutory requirement to achieve a 75% reductionin greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 and net zero by2045. The transport sector is currently the largestcontributor to carbon emissions, with road transportresponsible for the greatest share.In the Programme for Government of 2019, as part of a“Mission Zero” for transport, the Scottish Governmentmade the commitment to:“creating the conditions tophase out the need for all newpetrol and diesel vehicles inScotland’s public sector fleet by2030, and phasing out the needfor all petrol and diesel cars fromthe public sector fleet by 2025”.The Scottish Government’s commitment to public sectorfleet decarbonisation was underlined by its signature ofthe Climate Group ZEV Pledge for Public Fleets atCOP26.Over time it is expected that the total cost of ownershipof ZEVs will move closer to parity to that of internalcombustion vehicles and evidence suggests that benefitsincrease with higher vehicle utilisation. Considering this,Transport Scotland has signalled that future financialsupport is likely to focus on higher cost and specialistvehicles and infrastructure. Consequently, public bodieswill need to consider how they finance the on-goingdecarbonisation of their cars and vans and associatedcharging infrastructure.Meeting the electric vehicle infrastructure challenge 4

3.Purpose of this ReportThis report focuses on options available for publicbodies to deliver and finance the charginginfrastructure required to support the phasing out ofpetrol and diesel cars and vans from the public sectorfleet.The decarbonisation of the public sector fleet willrequire a mix of alternative technologies. Hydrogenfuelled vehicles may also form part of the longer-termdelivery plan where heavier vehicles with morechallenging duty cycles are involved. Whilst the focusof this report is on the likely need for EV charginginfrastructure, many of the principles outlined areapplicable when considering the need to decarboniseheavier duty vehicles and invest in the necessary refuelling infrastructure.This report summarises: Progress made in phasing out cars and vans fromthe public sector fleet. Barriers and opportunities in meeting theinvestment challenge. Options to optimise the infrastructure expansion. Options to finance the infrastructure expansion. Partnership models that could be adopted. The current procurement frameworks that could beadopted for future delivery.It concludes by suggesting the establishment of apathfinder initiative to test the viability and benefits ofa collaborative approach to assessing future chargingneeds as well as identifying alternative funding optionsto help accelerate the delivery of EV charginginfrastructure for public sector cars and vans.Meeting the electric vehicle infrastructure challenge 5

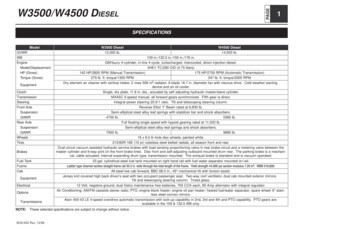

4.Progress in Phasing Out Cars& Vans from Public Sector FleetMany public bodies have made significant progresstowards decarbonising their fleet. Transport Scotlandhas supported the transition to electric car and vanfleets through its Switched-on-Fleets programme,administered by the Energy Savings Trust (EST).Through their funding programmes, Transport Scotlandhas invested over 60 million since 2014 deliveringaround 3,500 zero emission vehicles as well as over 800EV chargepoints for fleet users.In 2020 Transport Scotland commissioned Jacobs toanalyse the Scottish public sector fleet. The researchcovered over 95% of the public sector and showed thatthe total number of vehicles in the fleet at that timewas around 28,800, spread over 60 public bodies.Since then, there has been significant additionalinvestment in fleet decarbonisation across Scotlandand it is expected that figure will have increased.Whilst good progress has been made it is evident thatissues such as supply chain pressures and price inflationare extending the lead times for vehicles andinfrastructure. This reinforces the need to move at paceon establishing and implementing fleet rationalisationand decarbonisation strategies and delivery plans forcharging infrastructure.By far the largest categories were cars and LightGoods Vehicles (LGVs) totalling around 22,000 vehicles.Around 57% of the public sector fleet was within localauthorities and around 17% in health boards.For cars and LGVs the analysis showed that ZEVscomprised 946 cars (10.6%) and 435 LGVs (3.4%).The graph below illustrates the annual mileage bandsfor public sector cars and LGVs.Figure 2.Public Sector FleetCars and LGVs Miles / YearFigure 1.Public Sector FleetCars and LGVs14%9,46542%17%12,81358%52% 5,000 miles LGV Car9%9% 5,000 to 9,999 miles 10,000 to 14,999 miles 15,000 miles miles unknownMeeting the electric vehicle infrastructure challenge 6

5.Barriers in Meetingthe Investment ChallengeEST host regular public sector fleet decarbonisationforums. These forums are open to all public sector fleetmanagers. It provides a valuable platform to sharelessons learned and hear from industry experts onemerging opportunities and new ways of working. At arecent forum EST facilitated a workshop to take stock ofthe current delivery landscape and draw out the keybarriers to an effective transition to ZEVs.SFT also engages with local authority personnel in thepublic EV charging sector, many of whom are alsoresponsible for the transition of their fleet to ZEVs.Below is a summary of the key messages from recentengagement with public sector fleet managers.Upfront Costs – The higher upfront cost of purchasingZEVs and the additional cost of installing charginginfrastructure and the lack of certainty of future capitalfunding is of concern.Vehicle Options – Particularly for vans, there is concernthat there is not yet a range of vehicles available tomeet all operational requirements.Lead times – Given the well published global shortagein semi-conductors and the on-going impact of thepandemic, fleet managers are now being quoted longlead times for ZEVs.Skills and Resources – For many public bodies theavailability of personnel with the relevant experience totake forward this transition is a key barrier. This is likelyto be more acute in smaller organisations that may nothave large fleet management teams.Long Term Strategy – Many public bodies are stilldeveloping their long-term fleet strategy. Issues suchas the number and functionality of vehicles, electric vshydrogen, home vs depot charging, interfacing withestate management and finance colleagues as well assharing vehicles and charging infrastructure with otherorganisation is taking time to resolve.Power Supply – Whilst many depots are likely to havesufficient installed electrical capacity to accommodatestandard and fast chargers which are suitable for mostcars and vans, larger capacity chargers for more rapidcharging or for larger vehicles may need a newsubstations and grid upgrades which will take time andadd substantial costs.Staff Engagement – The feedback was that manyoperational staff within the public sector still have aperception that ZEVs have a limited range and thatlimited access to charging infrastructure couldconstrain their normal work patterns.Meeting the electric vehicle infrastructure challenge 7

6.Opportunities for Delivery6.1. Overview6.2 Shared Learning Forums & Knowledge HubsAs highlighted above, transitioning all of Scotland’spublic sector cars and vans to ZEVs is a significantchallenge but it also represents a major opportunity tocritically assess the role of cars and vans in the publicsector fleet, how they can support the way in which thedelivery of public services will evolve in the years tocome as well as supporting Scotland’s transition to alow carbon economy.This is already happening through the bi-monthly ESTfleet forum. Additional forums for shared learning alsoexist via the Society of Chief Officers of Transportationin Scotland (SCOTS), the Association for Public ServiceExcellence (APSE) as well as each of the seven RegionalTransport Partnerships and initiatives such as theemergency services’ Blue Light Working Group.Across Scotland there are many good examples ofpublic bodies working together to deliver complexchange and transformation programmes. Sharingresources and experiences to help identify the scale ofinvestment required and to plan and implementdelivery will be a key factor to the success of thisprogramme of change.Building on these forums for shared learning there ismerit in public bodies developing a shared fleetcharging Knowledge Hub that could capture sharedlearning, be a repository for best practice, standarddocuments, links to reference material, case studies aswell as offering a virtual discussion platform for publicsector personnel to openly exchange challenges,queries, and opportunities.At the heart of the suggestions below is collaborationand the investment hierarchy set out the ScottishGovernment’s Infrastructure Investment Plan. By workingcollaboratively opportunities will arise to optimise theinvestment required, maximise the utilisation of existingand new assets, co-locate and share facilities andminimise the need to access alternative sources offunding for new infrastructure.Post-Covid it is likely that use of public sector fleets willevolve to reflect new ways of working and in somecases this may mean the overall size of fleets canreduce. In addition, finding alternatives to travelling orusing more sustainable transport options can reducethe overall demand on the public sector fleets andcontribute to the target of reducing car kms travelledby 20%.The concept of collaboration should not only be viewedas a public-to-public initiative. Through collaboratingwith industry there is an opportunity to createinvestment opportunities which can help secureeconomies of scale, improve service delivery, andleverage additional sources of finance.Collaboration and shared learning between publicbodies will help identify new opportunities for moreaffordable and sustainable fleet management withinthe public sector.Meeting the electric vehicle infrastructure challenge 8

Opportunities for Delivery (continued)6.3 Shared Resources & Joint WorkingTaking shared learning to the next level could includepublic bodies sharing resources and budgets toincrease the efficiency and effectiveness of planningand delivering the required infrastructure.Through pooling resources and budgets, severalcollaborative short-life groupings could be mobilised bypublic bodies to plan and procure the requiredtransition in a manner that is aligned with other policypriorities such as the Place Principle.builds on concept of an interactive knowledge hub tohelp connect potential chargepoint hosts and serviceproviders looking for investment opportunities. Thisconcept was identified as one of the portfolio ofDemonstrator Solutions proposed by the Green FinanceInstitute in their publication Road to Zero – Unlockingpublic and private capital to decarbonise roadtransport.6.4 Optimising the Infrastructure CostsThis will help provide greater visibility of the investmentrequired, reduce the risk of duplication of effort andhelp present more attractive investment propositions tothe private sector.Given the scale of the challenge and the costs involvedit is important to critically assess what infrastructure isnecessary to meet operational needs and how theutilisation of charging infrastructure could be optimised.It can also aggregate the demand for EV chargepointsto help secure economies of scale and, throughbundling of low and high utilisation sites, help securecommercially viable propositions.ZEVs and the associated infrastructure are necessary tosupport the delivery of high-quality public services. Butas new ways of working are developed and technologyenables more flexibility working patterns, the transitionto ZEVs presents an excellent opportunity to assess howmany cars and vans the public sector fleet needs.This is already happening in many parts of Scotlandand the partnerships between Aberdeen City,Aberdeenshire, and Highland Council, the eightauthorities in the Glasgow City Region as well as North,South and East Ayrshires on their respective public EVcharging expansion plans are good examples ofcollaboration.As these joint working initiatives evolve this could see arange of delivery models begin to emerge.As mentioned above, the concept of joint workingshould not be seen as purely a public-to-publicinitiative. Through openly communicating investmentplans, opportunities may arise to secure even greatereconomies of scale through partnerships with theprivate sector.Private fleet operators will be facing similar resourceand financial constraints as they seek to decarbonisetheir fleets. Through public/private collaborationsinfrastructure investments which may not have beenviable as a standalone public sector initiative, couldbecome more deliverable as a result of sharing fixedcosts and increasing the utilisation of charginginfrastructure. This may also generate additionalincome for public bodies.To provide better visibility as to who is planning to dowhat in different parts of Scotland, commissioning anaccessible data base similar to SFT’s ConstructionPipeline Forecast Tool could be of assistance. ThisWhere the need to access a vehicle is incidental,shared mobility options such as pool cars and car clubsare well established alternatives to individual carownership.For most cars and small vans, where overnight chargingis available either at the depot or at the operator’shome, 3.7kW or 7.4kW chargepoints are likely to besufficient. The range of most electric cars and vanscould mean that access to overnight charging two orthree times a week may be sufficient. Where this canbe planned and complemented by access to the publiccharging network, the need for more expensive depotbased rapid and ultra-rapid charging for public sectorcars and vans could be reduced.With most cars and vans only needing to be chargedovernight two or three times a week, the introduction ofchargepoint booking or scheduling systems can helpreduce the number of chargepoints required andincrease the utilisation of the chargepoints installed.Historically fleet and public charging infrastructure hasbeen considered separately. Whilst recognising that inmany circumstances operational constraints will limit toopportunity for the public to access fleet charginginfrastructure, where shared access is possible it willhelp increase the utilisation of charging infrastructureand potentially generate additional income.Meeting the electric vehicle infrastructure challenge 9

Opportunities for Delivery (continued)Scottish Ambulance ServiceHome start initiatives are actively being considered byseveral public bodies. Installing a 7kW charger at anemployee’s home is a relatively affordable option andthere are solutions emerging that can capture workrelated charging hours. Supporting staff to access offpeak tariffs overnight can both help staff and theiremployers reduce their charging costs. Some suppliersare claiming over an 80% reduction in equivalent fuelcosts. This option can also generate other benefitsthrough increased productivity by reducing the time totravel to and from depots as well as helping contributeto the target of reducing car kms travelled by 20%.Whilst some depots may not have the necessaryelectrical capacity to accommodate rapid charges,one option is to consider installing restricted or loadmanaged chargers which can operate at a lowercapacity until such time as the local grid capacity isenhanced.As a final point, where possible, avoiding unnecessarycivil engineering works can help reduce the overallinstall cost. Wall mounted units can avoid the need forexpensive earthwork and resurfacing activities.6.5 Operating NetworksPublic bodies currently adopt the ChargePlaceScotland (CPS) operating network which provides thenecessary back-office management function. Atpresent the costs of running CPS are paid by ScottishMinisters. Transport Scotland has signalled the need tobuild on the lessons learned in developing the CPSScotland network. However, the intention is to notextend the current subsidy arrangement beyond theexpiry of the current back-office contract meaningpublic sector fleet owners will need to begin developingoptions for procuring a back-office service.CPS was established to provide the EV car driver with aunified national brand, ensuring that publicchargepoints across the country could be easilyaccessed. Chargepoints with restricted, or no, publicaccess does not add to this public network.From a fleet management perspective, public bodiesshould consider whether a centralised chargepointmanagement system can deliver the best results fortheir organisation. Real time information on chargepointavailability, reliability, utilisation and maintenance maybe better obtained from a management systemdedicated to the organisations own network of fleetchargepoints. Taking direct responsibility forchargepoint management may assist in improvingoperational performance as it allows public bodies toset their own Key Performance Indicators.To help facilitate this approach, Transport Scotland haspledged to support the Blue Light Services WorkingGroup in the development of a common back-officesystem which could be a useful template for otherpublic sector fleet operators.Meeting the electric vehicle infrastructure challenge 10

7.Funding & Financing Options7.1 Background7.3 UK Infrastructure BankPublic bodies have traditionally funded fleetdecarbonisation activities through capital budgets,either through their own or via grant funding fromTransport Scotland. To date, the total costs have beenproportionately low, but as the number of electricvehicles in the public sector fleet increase in line withthe commitment to phase out the need for all petrol ordiesel cars, so will the associated spend oninfrastructure. It is therefore likely that public bodies willneed to consider alternative funding and financingmechanisms.The UK Infrastructure Bank (UKIB) was set up by the UKGovernment in June 2021 as a government-ownedpolicy bank, focused on increasing infrastructureinvestment across the UK.Many of the Region and City Growth Deals identifiedlow carbon initiatives as a priority. There may besynergies with outcomes and priorities of low carbon inthese growth deals with the need to expand fleetcharging infrastructure.Future bids to the UK Government’s Levelling Up fundmay also present opportunities to secure funding forfleet infrastructure.For some local authorities the most practical financingoption may be to approach the Public Works LoanBoard.Where the preference is to adopt private finance,creating the conditions to attract private capital to thissector will be important.Any borrowing should be supported by a strongbusiness case and an assessment against eachorganisation’s respective borrowing rules.7.2 Leveraging Local Authorities’ BorrowingCapacityThere is the potential for local authorities to work withother public bodies who do not have access toborrowing powers and procure charging infrastructurecapacity which could be accessed by multiple publicbodies.Local authorities could increase the utilisation of theirassets by charging partner organisations an agreedtariff for shared access to charging infrastructure theyprocure.UKIB can however finance initiatives across both theprivate and public sector. UKIB can lend up to 4bn tolocal and mayoral authorities for strategic and highvalue projects of at least 5 million.Where Scottish local authorities collaborate andidentify EV charging initiatives at scale, the UKIB maybe an alternative or complementary source of finance.The Scottish National Investment Bank (The Bank)provides patient (long term) capital to businesses andprojects throughout Scotland that are aligned with itsMissions. The Bank’s sole source of funding is FinancialTransactions from Scottish Government which can onlybe used to lend to private sector entities and istherefore not a potential source of finance for publicbodies.7.4 Community Municipal InvestmentsThis is part of the portfolio of demonstrator solutionsproposed by the Green Finance Institute in theirpublication “Road to Zero – Unlocking public andprivate capital to decarbonise road transport”.Community Municipal Investments (CMIs) are bonds (orloans) issued by local authorities and administered by aregulated crowdfunding platform. They offer a way forthe public to participate in the financing of local lowcarbon initiatives.Climate bonds were launched by West BerkshireCouncil and Warrington Borough Council in the Summerof 2020. Each met their 1m target. In 2021 the LondonBorough of Islington issued CMI to support Islingtonbased projects that tackle climate change. Last yearBlaenau Gwent County Borough Council approved a 2m CMI and became the fourth authority in the UK toapprove a community bond to finance carbonreduction projects.Meeting the electric vehicle infrastructure challenge 11

Funding & Financing Options (continued)7.5 LeasingLease finance is widely available for both vehicles andcharging infrastructure, either on an operating orfinance lease basis. Operating leases tend to haveshorter terms and finance leases may have an optionto purchase or allow for asset transfer at the end of thelease.A lease finance model can reduce or eliminate theneed for upfront capital funding from the public sector.The required capital investment is converted into anoperational charge paid for either per mile, per kW oras fixed monthly fee. In addition, some vehicle leasingcompanies are offering charging miles/hours as part ofthe monthly lease charge.There are operators who can offer a fully financedturnkey solution of EV charging infrastructure. As well asthe cost of the charging infrastructure this can includethe cost of grid connections, vehicle-batterymanagement as well as software packages to enableeffective fleet management.Lease costs can also include training and maintenanceservices as well as options to upgrade the scope ofservices during the lease.In accounting terms, finance leases have historicallybeen classified as equivalent to a borrowing and shownon-balance sheet; operating leases are not shown onthe balance sheet. The adoption of IFRS 16 by thepublic sector for the accounting period starting April2022 will change this, such that any operating leasewith a duration of greater than 12 months will, broadly,be capitalised on-balance sheet as well.For central government bodies, budgetary treatmenttends to follow accounting treatment. Therefore, capitalbudget cover is expected to be required from 1st April2022 for new operating leases and therefore leasefinance may not be a viable option for suchorganisations. Where capital budget is available, theremay be a preference to purchase vehicles orinfrastructure outright.For local authorities the consolidation of liabilities onbalance sheet (in this case from operating leaseliabilities) does not generally have a budgetaryimplication unless there are directly associated revenuegrant payments from Scottish Government (i.e.,supported borrowing). Therefore, lease finance may bea viable alternative for local authorities.2 Source - Blaenau Gwent CBC: Blaenau Gwent - first five UK councils to join national Local Climate Bonds campaignMeeting the electric vehicle infrastructure challenge 12

Funding & Financing Options (continued)7.6 Supplier FinanceHistorically supplier finance meant the supplier offeringfunding through a third party or in-house creditprovider – essentially leasing or hire purchase deals.Increasingly, however suppliers are looking to offer otherforms of financing, particularly where it can support alonger-term relationship with a public sector partner(typically at least 10 years). “Charging-as-a-service” isone example, which would involve the private sectorpartner/supplier offering a range of products andservices bundled together in exchange for a regularpayment. This tends to be more applicable toinfrastructure than fleets, although “vehicles-as-aservice” is also a developing market.The principal objective may be characterised as thesale/purchase of an electric vehicle charging andmanagement service, rather than purely a purchase ofcharging infrastructure or electricity. This potentiallycould include some, or all, of a range of services: Energy solution assessment and design EV fleet migration planning Ongoing EV fleet management Back-office system management Supply of smart energy systems Fleet management information Electricity/Fuel supply Remote charge point monitoring and maintenance Renewable energy supply – electricity or hydrogen Battery finance (for larger vehicles) Hardware supply, installation, and commissioning Long term maintenance Assessment of external revenue opportunitiesThe public sector partner pays for the provision of theservice over time, usually against an agreed set ofperformance criteria. The cost can be expressed asp/kWh charge, or as a fixed amount or linked toutilisation – much will depend upon the partner’sperception of the risks involved and its willin

INFRASTRUCTURE CHALLENGE APRIL 2022. Meeting the electric vehicle infrastructure challenge 1. . authorities and around 17% in health boards. For cars and LGVs the analysis showed that ZEVs. comprised 946 cars (10.6%) and 435 LGVs (3.4%). . is available either at the depot or at the operator's. home, 3.7kW or 7.4kW chargepoints are likely .