Transcription

Trade inTransition2022Sponsored by

Trade in Transition 20222Contents2Contents3Foreword by DP World4About this research5Executive summary7The global trade landscape: the great recovery?18 Sector deep dive27 Regional insights50 Global trade’s turbulent future The Economist Group 2022

Trade in Transition 20223ADVERTISEMENTForewordby DP WorldSupply chains never sleep and the eventsof the past year have seen them reconfiguredaround the world for almost everythingwe produce.Sultan AhmedBin SulayemGroup Chairmanand CEO, DP WorldThese uncertain times show that digital trade,speed of delivery and transparency for cargoowners are key to helping exporters andimporters provide the goods we all need –on time and in the quantities we require.We have seen many headlines recentlyabout broken supply chains. Inflation,labour shortages and a lack of infrastructuredevelopment are all impacting the efficiencyof cargo movement to regional andinternational markets.While I remain mindful that this third year ofcovid-19, as well as intensifying geopoliticaluncertainty, could continue to hinder the globaleconomic recovery, I believe there are calmershores ahead. I hold firm to my belief that globaltrade has lifted – and will continue to lift – largeparts of the world out of poverty, creatingbetter access to jobs, education and healthcare.As a global logistics business, DP World willcontinue to help not only to rebuild, but tobuild back better, with the outlook for 2022remaining encouraging, despite the dark cloudsthat commentators may see around us.That is why it is so important to keep ourfingers on the pulse of the logistics sector, sothat supply-chain professionals and those inthe frontline of these developments can viewthe key trends and issues at first hand, and seewhat is impacting the world of trade over time.With our sponsorship of the global Tradein Transition survey, conducted by EconomistImpact, we capture private-sector opinion onthe issues facing international trade, whichserves as an important barometerof sentiment.I am proud to launch the second edition ofTrade in Transition. We have uncovered anumber of notable insights: 48% of seniorexecutives are diversifying their supplychain bases, and are changing their strategicoutlook to help to ease inflationary pressures.“Just-in-time” delivery is being overtaken by“just-in-case” contingency planning, to dealwith both expected and unexpected surges indemand and supply-chain shocks – with 27%of businesses now on average holding one- tothree-month buffers of stock.We are all reliant on key infrastructure alongvital trade routes. To keep cargo flowing, weare working with governments and partners.Through infrastructure investment andimproved customs procedures, we will keepstriving to lower the cost of trade and enablethe growth of business in whatever form.I look forward to the rest of 2022 andbeyond. Trade is indeed in a state oftransition, but it always has been sincethe beginning of time – and it will continueto be for the foreseeable future.Sultan Ahmed Bin Sulayem,Group Chairman and CEODP World The Economist Group 2022

Trade in Transition 20224About this researchTrade in Transition 2022 is an Economist Impactresearch programme, sponsored by DP World,which captures private-sector sentiment oninternational trade. In the inaugural programme,launched in 2021, we explored the impact ofcovid-19 on companies’ trade operations. Inthe second year, we explore how companiesare navigating the ups and downs of the globaleconomic recovery against the backdrop of anongoing pandemic.This year’s research is also based on a global surveyof senior executives involved in their firms’ day-today international trade decisions and transactions.The survey of 3,000 respondents was conductedbetween October and December 2021, capturingthe perspectives of executives across six regions(North America, South America, Europe, MiddleEast, Africa and Asia-Pacific).The survey findings were supplemented by in-depthinterviews with trade experts and senior executivesacross regions and sectors. We would like to thankthe following experts for their time and insight: Lakshmanan Chidambaram, president Americas strategic verticals, Tech Mahindra Jaime Granados, division chief - tradeand investment division, Inter-AmericanDevelopment Bank Anderson Martins, head of supply chain,Nestlé Philippines Marc Mealy, senior vice-president of policy,US-ASEAN Business Council Mahender Nayak, head of India, CIS, MiddleEast, Turkey and Africa, Takeda Stephen Olson, senior fellow, HinrichFoundation Tamara Oyarce, national trade policy andresearch manager, Export Council of Australia Sulaiman Pallak, general manager - salesoperations, General Motors Middle East Ashish Thakkar, board member, MaraPhones Pakorn Thampimukvatana, director - supplychain, Danone India and South-east Asia Juliana Villegas, vice president - exports,ProColombia Michael White, chief executive officer, GTDSolution (a division of A.P. Moller Maersk) Deborah Elms, executive director, AsianTrade CentreThe report was produced by a team of researchersat Economist Impact, including: Vanessa Erogbogbo, chief - sustainable andinclusive value chains, International TradeCentre (ITC)John Ferguson – Project director Simon Evenett, professor, University of StGallen and founder of Global Trade AlertChristopher Clague – Project managerMelanie Noronha – Project managerAshish Niraula – Analyst The Economist Group 2022

Trade in Transition 20225Executive summaryThe past two years have been turbulent forpeople, governments and companies across theworld in ways that no one could have predicted.After the initial shock in 2020, demand hasrebounded, companies have reconfigured anda few economies have even recovered. Indeed,a resurgence in demand had been expectedafter the sharp fall in 2020, but not at the paceobserved in 2021. In October last year, the WTOrevised its 2021 forecast for global trade growth to10.8%, up from 8.0% estimated earlier in the year.1The Economist Intelligence Unit estimates thatglobal trade growth grew by 9.9% year on year in2021, following a 4.9% decline in 2020.A closer look reveals an uneven recovery indifferent parts of the world and across differentsectors. In this report, we examine the nuancesin trade operations by region and sector,presenting corporate perspectives on engaging ininternational trade through the covid-19 storm.The key findings of this report are:Global demand recovered much faster thanexpected. Results from our survey show that 68%and 62% of respondents reported an expansion inexports and imports, respectively, compared with42% and 48% in 2020. Growing demand was thetop driver of export and import expansion in 2021,cited by 36% and 43% of respondents, respectively.The surge in global demand, combined withsupply shortages, is increasing inflationarypressures. New waves of covid-19 cases led todisruptions in business operations, as staff hadto stay away from work to quarantine or recover,reducing output in some industries. In others, suchas agricultural or microchip production, supply isrelatively inelastic and producers cannot easily rampup output to meet changes in demand. Together,these factors are resulting in supply shortagesfor critical raw materials from microchips to milkpowder that are driving up prices. In response,companies have diversified their supplier bases,purchasing buffer inventories from suppliers thatmay be more expensive; some of this is being passedon to the consumer in the form of higher prices.High transport costs are expected tobe the top challenge in 2022. With sporadiclockdowns at ports, and increasing health andsafety measures, there have been long delaysat ports worldwide, creating a logistics challenge.In addition, with companies keen to maintainlarger inventory buffers closer to their facilities(see below), warehouses have been in highdemand. Thirty per cent of executives surveyedexpect higher transport costs to be the toplimitation for export growth in 2022, as plannedexpansion in port and logistics infrastructurewill take months to complete.1 World Trade Organization, ‘Global trade rebound beats expectations but marked by regional divergences’, WTO press release, October 4th 2021. https://www.wto.org/english/news e/pres21 e/pr889 e.htm The Economist Group 2022

Trade in Transition 2022Just-in-time is dormant. One of the clearesttrends during the pandemic has been the shift awayfrom efficiency to resilience, from “just-in-time”to “just-in-case”. Only 14% of companies surveyedare using a “just-in-time” approach to supplychain management. Instead, executives prefer tobuild inventory buffers. Twenty-seven per centof executives, the highest share, stated that theircompanies are holding one-to-three-month buffersand 26% are holding two-to-four-week buffers.Given the redundancies this builds into a business,executives must seek efficiencies in other ways,such as using advanced technologies to streamlineoperations or implementing sustainability measuresto reduce resource consumption.Corporate supply-chain ESG initiatives focuson the ‘E’, strategies that are generating aclear return in the short to medium term.The top two ESG strategies cited in our surveywere reducing product waste (33%) andminimising use of resources, such as waterand energy (31%). Working with suppliers thatensure fair labour practices and that are inclusivefeature in the bottom half of the list of strategies.No wonder then, that executives expect aclear, positive financial return from their ESGinitiatives: 47% of executives surveyed expectit within one to three years of implementation.Moreover, companies see ESG as a licence tooperate, without which they will lose accessto key markets and clients.As companies reconfigure their supplychains, most are diversifying their supplierbase regardless of location, rather thanregionalising. Forty-eight per cent ofrespondents chose diversification regardless oflocation as their primary reconfiguration strategy,whereas only 12% of respondents were primarilyregionalising and 5% were re-shoring. Meanwhile,36% of respondents are choosing to work withfewer suppliers by reducing the number of tiers intheir firms’ most critical supply chains.6Companies reconfigured their supplychains faster than expected and, overall,supply chains held up during the pandemic.On average, executives reported that it took7.9 months to reconfigure supply chains,compared with 8.5 months estimated in the 2020survey. This is testament to the agility of privatesector companies as they navigated pandemicrelated restrictions. Reconfiguration efforts weredirected mainly towards improving sourcing ofraw materials (24%), managing shipping lines andlogistics (21%), and ensuring health and safetyalong the supply chain (20%). Surprisingly, only7% of executives felt that introducing advancedtechnologies was the most critical part of theirreconfiguration efforts.But the use of advanced technologies willbe an important source of efficiency in tradeoperations and can help to address non-tariffbarriers. Forty-three per cent of respondentscited new technologies as the top reason to beoptimistic about international trade. Although over60% of companies surveyed were already usingdigital platforms before 2021, last year companiesincreased their adoption of 5G technologies (36%),digital solutions to enable seamless movementthrough customs (34%) and advanced automation(33%). The highest share of respondents (22%) saidthat 3D printing was not applicable to their tradeoperations. However, there are some interestingexamples of implementation in the industrial sectorthat have the potential to transform sourcingpatterns in the coming years.Executives surveyed are optimistic abouttrade growth in 2022. Seventy-four per cent ofrespondents expect exports to expand and 68%expect imports to expand this year. Although thesurvey was fielded prior to the Omicron surge,experts interviewed in January 2022 have said thatalthough there may be some additional restrictions,these are likely to be temporary and are unlikely toimpact the outlook for trade recovery for the year. The Economist Group 2022

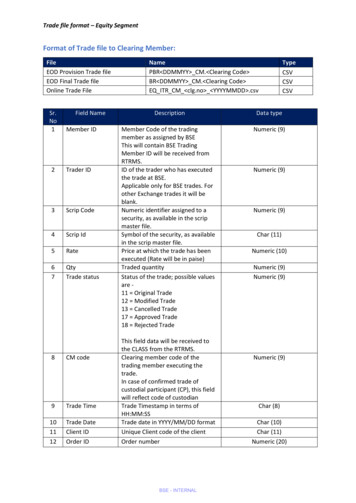

Trade in Transition 20227The global trade landscape:the great recovery?After a disastrous 2020, global trade in goodsappears to have experienced a robust recoveryin 2021. According to figures from the UNConference on Trade and Development(UNCTAD) released in early December 2021,goods trade was estimated to be 15% abovethe pre-pandemic level, although the reportnotes that the estimates were made prior tothe spread of the Omicron variant.2 This largelycomports with the results of Economist Impact’ssecond annual Trade in Transition global surveyof 3,000 executives, sponsored by DP World.Asked about their firms’ international salesduring the first three quarters of 2021, comparedwith the same period in 2020, more than 67% ofrespondents answered that sales had expanded,with just 17% reporting a contraction; 15% ofrespondents reported that sales had been flat.On average, companies covered by our surveygrew exports by 16%.Figure 1: Change in company-wide exports between 2020 and 2021 (Q1-Q3)Expanded by 50% or more12%Expanded between 30-49%15%Expanded between 10-29%23%Expanded by less than 10%18%Flat15%Contracted by 0-10%Contracted by 10-29%8%5%Contracted by 30-49%2%Contracted by 50% or more2%Source: Economist Impact2United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, ‘Global merchandise trade exceeds pre-COVID-19 level, but services recovery falls short’,December 9th 2021. short The Economist Group 2022

Trade in Transition 20228Three factors drove the recovery in exports,according to our survey. The primary driver was“growing demand in key markets”, cited by 36%of respondents as a cause of expansion in theirinternational sales. This was followed closely by“expansion of operations into new markets”, at 35%,and “expansion of operations in existing markets”,at 25%. On the import side, 43% of executives alsoreported that growing demand and consequentincreased production levels was a key driver behindthe recovery, while 32% said – encouragingly, as thishas long been a concern around the globe – thatimproved ports and logistics infrastructure was oneof the main contributing factors.By region, firms surveyed in South Americareported the highest rate of growth in exports,at 25% on average. This again largely alignswith forecasts, including that of the EconomicCommission for Latin America and the Caribbean,another UN agency, which also predicted a 25%rise in the value of exports, mainly – but notsolely – because of the rise in commodities pricesover the course of the year, particularly for energyand agricultural goods.3 At the other end of thespectrum, among firms surveyed in North America,the average export expansion was just 14%, areflection in part of their ability to rely on domesticdemand rather than overseas markets to drivesales. Firms in Africa and Asia-Pacific reported onlyslightly larger expansions on average, at 15%.All the numbers for 2021 are nevertheless mostlyencouraging. But that was to be expected, in theabsence of a massive surge in covid-19 cases. “Itwas inevitable after the contraction in 2020,” saysSimon Evenett, professor of international tradeand economic development at the University ofSt Gallen in Switzerland and founder of GlobalTrade Alert, a monitor of global protectionism andcommercial policy. “The question is how fast [it]would happen and how far it would go.”The answer appears to be fairly fast and fairly far.Figure 2: Growth drivers for exports and imports in 2021Drivers of export growthGrowing demand in key markets36%Expansion of operations into new markets35%Expansion of operations in existing markets25%Adoption of competitive pricing strategies in key markets20%Lower transport costs13%Improved logistics and port infrastructure in key markets11%Sector promotion policies by governments in key markets11%Improved efficiency due to digitisation of supply chains10%Lower tariffs in key markets9%Improved access to trade finance8%Reduction of non-tariff barriers7%None of the above6%0%Source: Economist Impact5%10%15%20%25%30%35%40%Increase in production levels driven by growing demand43%Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, ‘The region’s trade will increase significantly in 2021, but the recovery will be asymmetricalandheterogeneous in a Improvedcontext significantly-2021-recovport and logistics infrastructure in your country of le government policies in your country of operationsLower transport costsImproved efficiency due to digitisation of supply chainsLower tariffs/custom duties in your country of operations24%20%19%17% The Economist Group 2022

Expansion of operations into new marketsTrade in Transition 202235%Expansion of operations in existing marketsAdoption of competitive pricing strategies in key markets20%Lower transport costs13%Improved logistics and port infrastructure in key markets11%Sector promotion policies by governments in key markets11%Improved efficiency due to digitisation of supply chains10%Lower tariffs in key markets9%Improved access to trade finance8%Reduction of non-tariff barriers7%None of the above6%0%Drivers of import growth925%5%10%15%20%25%30%Increase in production levels driven by growing demand35%40%43%Improved port and logistics infrastructure in your country of operations32%Favourable government policies in your country of operations24%Lower transport costs20%Improved efficiency due to digitisation of supply chains19%Lower tariffs/custom duties in your country of operations17%Favourable foreign exchange movements (that reduced the cost of imports)16%15%Reduction of non-tariff barriers in your country of operations (e.g. quotas)6%None of the above0%10%20%30%40%50%Source: Economist ImpactFigure 3: Average expansion in exports and imports, global and by region(2021 and expectations for 2022)Export growth 2021Export growth expectation 2022Import growth 2021Import growth expectation 7%1 5%14%12%11%13%12%15%11%15%15%12%9%GlobalNorth America South AmericaEuropeMiddle EastAfricaAsia PacificSource: Economist Impact The Economist Group 2022

Trade in Transition 202210A rotation aheadsame for imports (inputs). Both figures are higherthan those for 2021. The overall global averageexpectation is for exports to expand by 19% overthe coming year.Will this recovery endure? Our survey resultsindicate widespread optimism among globalexecutives that it will, although as with theUNCTAD report referenced above, the surveywas conducted before the spread of the Omicronvariant, which could – along with a host ofother factors – inhibit output, the functioningof logistics and thus trade flows. Seventy-fourper cent of respondents, however, expectexports to expand in 2022 and 68% expect theThere is cause for caution, at least as far astrade in physical goods is concerned. For all thehand-wringing in the media and the myriadof consulting reports published, supply chainsdid continue to function during the peak of thepandemic and goods continued to flow aroundthe globe. But the strong demand for goods isFigure 4: Concerns with global trade over the next two years (2022-24)Ongoing trade war between the US and China30%Risk of rising inflation due to pandemic-related supply chain disruptions29%Covid-19 variants forcing many countries back into lockdown21%The division of the world into trade blocs / regionalisation19%Global warming16%Public opposition to trade14%Rising protectionism13%The demise of the WTO11%Outdated/inadequate infrastructure11%Terrorism, military confrontation and geopolitical upheaval in the Middle East/North Korea/Africa9%Labour unrest8%Cybersecurity breaches6%Instability caused by Brexit5%Human-induced disasters (for example, Suez canal blockage)4%Ageing populations with fewer in the workforce3%Source: Economist Impact The Economist Group 2022

Trade in Transition 202211likely to abate, says Ben Simpfendorfer, chiefanalyst at the Pacific Basin Economic Council,an advocacy organisation, and the author ofThe New Silk Road, which explored the emergingeconomic relations between the Middle East anda rising China. “We are going to get a rotationin consumer demand,” says Mr Simpfendorfer,“away from goods towards services as[consumers], rather than ordering productsonline at home, begin to move back out ontothe streets, into bars, into restaurants and takingup other types of service activities.”This would mark a resumption of one of the keytrends in global trade already under way priorto the pandemic. Trade in services, althoughstill smaller in value than trade in goods, wasestimated to be experiencing much strongergrowth and was forecast to continue to do so inthe years ahead.4 The pandemic was certainlya massive disruption, but as most of the worldreturns to some semblance of normality, it is hardto doubt Mr Simpfendorfer’s assertion.Risky businessMore broadly, some very real problems haveaffected supply chains – and trade in general – overthe past few years. There are persistent issues thatcould remain unresolved in the years ahead, or evenpermanently. Stephen Olson, a senior fellow at theHinrich Foundation, a trade-focused non-profitorganisation, and a former US trade negotiator,holds something akin to this view. “When I take astep back,” Mr Olson says, after considering the2021 recovery in trade, “and I look more broadlyat the trade landscape, I think things are going toget more contentious, more acrimonious. Morechallenging, not less challenging.”The main source of acrimony – or reason forpessimism, as we phrased it in our survey – is4OECD Data, Trade in goods and services (indicator). doi: 10.1787/0fe445d9-en. vices.htm#indicator-chart The Economist Group 2022

Trade in Transition 202212the US-China trade conflict. There was hopethat the Biden administration might seek out anamicable resolution to the disputes that havelong plagued the bilateral relationship, but tradeis clearly not at the top of the administration’sagenda and so little has changed from the Trumpyears; the tariffs and other barriers imposedduring the Trump presidency largely remain inplace and the prospects of them being liftedsoon, if at all, appear dim.That neglect, whether benign or malign, alsoapplies to the WTO. It ranks in the middle ofthe list of concerns for the future of trade, andthis should probably worry the executives whotook part in the survey. There is a distinct lackof appreciation for the WTO’s role in governingglobal trade in a reasonably fair manner overthe past 25-plus years. Without a WTO orsimilar body, we may be entering into an era ofwhat Mr Olson calls “the new realism”, a morepragmatic, less doctrinaire approach to trade thatis likely to be determined more by the rules of(geopolitical) power than the rule of law. That isgoing to prove a difficult environment for manyfirms in ways they have not yet imagined.The risk of rising inflation as a result of thepandemic came second among concerns about thefuture of trade – just behind the US-China tradewar – cited by 29% of respondents. The faster thanexpected surge in demand, combined with supplyshortages, is creating an inflationary environment.Shortages in 2021 arose for two main reasons.First, new waves of covid-19 cases meant thatemployees were required to quarantine or recover,disrupting business operations, particularly atfacilities that require staff on site. This led to lowerlevels of output, driving shortages. In other sectors,such as agriculture and microchips (see moredetails in “Sector deep dive”, in the next chapter),supply tends to be relatively inelastic and so couldnot keep pace with the surge in demand.Rising costs, which most firms absorbed duringthe pandemic to varying degrees, are now beingpassed on to consumers, most notably in the US. InJanuary 2022 consumer prices rose by 7.5% from theyear-earlier period, with food prices increasing by 7%and energy prices by 27%.5 Globally, the EIU forecastshigher inflation in 2022, at 6.2% overall, comparedwith 5.2% in 2021. Once supply adjusts during thecourse of this year, inflationary pressures will ease.The EIU forecasts global inflation of 4.3% in 2023.Figure 5: Most crucial areas for supply-chain reconfigurationSourcing raw materials24%Shipping lines and logistics service providers21%Health and safety along the supply chain20%Warehouse management13%Re-staffing11%Introduction of advanced technology along the supply chain7%Resilience and contingency planning4%Source: Economist Impact5U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, Consumer price index – January 2022. https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/cpi.pdf The Economist Group 2022

Trade in Transition 202213The great reconfigurationThe complex trading environment and pandemicrelated challenges are driving companiesworldwide to reconfigure their supply chains. Buteven before the onset of covid, companies werethinking about making changes to their supplychain networks. A mix of factors, including risinglabour costs in China, protectionism sparked by theTrump administration’s trade policy, and countriespursuing more (and more ambitious) bilateral and“mega-regional” trade agreements were reportedto be causing firms to reconfigure productionnetworks to make them more robust and to takeadvantage of potential new opportunities. But thiswas harder than expected. Deborah Elms, founderand executive director of the Asian Trade Centre, aSingapore-based think-tank, maintains that thereare a variety of explanations. “[Companies] hadn’texecuted for a lot of reasons,” says Ms Elms. “It’sdifficult, it’s complicated and it’s expensive. Youcan’t find the right staff and so on.”However, pandemic-related supply-chaindisruptions spurred increased action on this front.In our September 2020 survey, 83% of executivessurveyed around the world stated that their firmswere in the process of reconfiguring their supplychains. Data from our survey in 2021 showedthat, on average, executives reported that it took7.9 months to reconfigure supply chains, comparedwith an estimate of 8.5 months estimated in the 2020survey (although supply chains were stickier in someindustries, such as food and agriculture, which relyheavily on some countries for certain ingredients).Nevertheless, as of December 2021, 9% ofrespondents stated that their firms were still inthe process of reconfiguring their supply chains.Ms Elms believes that if China, in particular,continues with its current, stringent policy tocombat the spread of the Omicron variant, morefirms are going to start executing their longanticipated relocation strategies.But what “reconfiguration” entails may varyfrom firm to firm. For those that have started toreconfigure their supply chains or have alreadydone so, three considerations stand out. Chiefamong these was the sourcing of raw materialsFigure 6: Primary approach to supply-chain reconfiguration5%12%36%48%Source: Economist Impact The Economist Group 2022

Trade in Transition 202214big opportunity for Colombia, that›s why now wehave a very strong strategy for ‘friend-shoring’,”says Juliana Villegas, vice president - exports atProColombia, an export promotion agency inthe country. “We have competitive advantagesincluding cheaper freight by air, sea and land.”during the pandemic, cited by 24% of surveyrespondents. This was followed in almost equalmeasure by shipping lines and logistics providers(which we take to mean the availability and costof these services) and health and safety along thesupply chain (in reference to the supply of labour inlockdowns and the ability of goods to move acrosscertain borders).More broadly, the diversification strategy supportsthe shift from “just-in-time” to “just-in-case” thattook place during the pandemic. Our surveyresults show that just 14% of companies globallyare operating just-in-time (only respondents inAfrica had a significantly higher share, at 22%).The highest share, 27%, are maintaining one- tothree-month buffers, and 26% are maintainingtwo- to four-week buffers of inventory.As companies focus on sourcing raw materials,their primary approach has been to diversifytheir supplier base, regardless of their location,rather than regionalising (see Figure 6). Fortyeight per cent of respondents to our survey werediversifying their supplier base, compared with12% of firms that were primarily regionalising and5% that were re-shoring.Trusting in techFor companies in regions that are underrepresented in global value chains, this is anopportunity to get involved. This includescountries ranging from Colombia and Ecuadorin South America to Saudi Arabia in the MiddleEast and Vietnam in Asia. “It is definitely a very“Supply-chain management is about informationmanagement,” says Pakorn Thampimukvatana,supply-chain director for India and Southeast Asia at Danone, a multinational companyfocused on dairy, plant-based and nutritionFigure 7: Building buffers in inventoryJust-in-time2%2 weeks27%26%15%14%Global1-3 months3%4%11%10%5%11%2-4 weeks1%4%27%28%26%25%13%3-6 monthsEnergy 1 od &beverage5%10%25%26%26%13%11%10%11%Health &pharmaIndustrial18%19%2%27%26%20%10%6-12 months2%14%16%Logistics &distributionSource: Economist Impact The Economist Group 2022

Trade in Transition 202215products. As companies navigate a risky tradingenvironment, they are increasing their adoptionof a suite of technologies, which together enablebetter information management and promisegreater visibility, predictability and, perhaps mostimportantly, eff

The Economist Group 2022 Trade in Transition 2022 4 About this research Trade in Transition 2022 is an Economist Impact research programme, sponsored by DP World, which captures private-sector sentiment on international trade. In the inaugural programme, launched in 2021, we explored the impact of covid-19 on companies' trade operations. In