Transcription

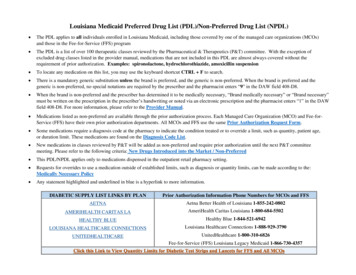

Spring/Summer 2021LouisianaWILDLIFEINSIDERp.6p.10IN THIS ISSUEP.2Letter From the EditorP.2Louisiana Youth Conservation Organization AwardP.3Deer Browse: How Much Does it Take?by Jimmy ErnstP.6Louisiana’s 2020 Private Lands Conservation Championsby David Breithaupt & Chris DoffittP.9Food Plots: Planting vs Natural Vegetation in PinePlantationsby Mitch SamahaP.10Louisiana Natural and Scenic Rivers Systemby Carrie SalyersP.13A Case for Keeping Wood in Our Streamsby Matt WeigleP.16Boots on the Groundby Bradley BrelandP.20Real Life Cryptid: The Search for the Eastern Spotted Skunkby Jennifer ManuelP.24We Can’t Manage or Protect What We Can’t Identifyby Brian Sean EarlyP.26Volunteer Profile: Mr. Joe HendersonP.26Featured WMA: Bayou Pierre Wildlife Management Areaby Jeff JohnsonPhoto by Margaret CrosbyP.29WMA Recreational Opportunitiesp.20P.30Featured Biologist: Paul LinkP.30Wildlife Management Calendar of EventsP.31Featured Biologist: Ruth ElseyP.32Wildlife Staff DirectoryP.34Coastal & Nongame Resources Staff DirectoryP.35Habitat is the PointBACK COVERPhoto byJerry W. Dragoo,newsweek.comRecovering America’s Wildlife Act (RAWA)

LETTER FROMTHE EDITORDear Readers,The year 2020 was definitely a year for thehistory books. We will undoubtedly see manychanges throughout the new year. There willbe many choices that we will all face as 2021moves along. We hope that you will chooseto take time for rest and relaxation. Take timeto travel to lands far away, if only in a book.“There is no frigate like a book to take us landsaway ” was penned by Emily Dickinson in themid-1800s. Allow the articles within this issueof the Louisiana Wildlife Insider to take youto lands away, lands scenic and aboundingwith wildlife. And remember, if you have aquestion about one of the wild critters thatmakes its home in Louisiana, we have theprofessional staff to provide you an answer.Look in the back of this issue for the rightindividual and give them a call.Sincerely,Jeffrey P. Duguay, Ph.D., EditorEric Shanks, Associate EditorKenny Ribbeck, Chief, Wildlife Division2Louisiana Youth ConservationOrganization AwardThe Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries (LDWF) Archery in Louisiana Schools Program (ALAS) has been named the 2019 Louisiana Youth Conservation Organization Award winner in the 56th annual state Conservation AchievementAwards, presented by the Louisiana Wildlife Federation and the National WildlifeFederation.LDWF’s ALAS program, part of the National Archery in Schools Program (NASP),introduces students in grades 4-12 to international target style archery and is generally taught as part of in-school curriculum. The program, founded in May of 2012,now serves more than 200 Louisiana schools and about 23,000 students.“I’m so proud of the job our ALAS team has done with this outstanding program,’’ LDWF Secretary Jack Montoucet said. “We appreciate the Louisiana WildlifeFederation and the National Wildlife Federation recognizing ALAS with the YouthConservation Organization award. This program is a gateway for students in ourstate to discover the great sport of hunting. We’re excited about the future for ALASand the impact it will continue to make.’’“One of the nice things about ALAS is that you don’t have to be the strongestor the fastest athlete to take part, and it’s designed so that all students can learnabout archery and participate,’’ said Chad Moore, who oversees the ALAS programfor LDWF. “But, it’s more than just participating. It’s about learning something mostknow nothing about, then becoming proficient at it. The focus and discipline usedto develop this proficiency then crosses over to other aspects of the student’s life,including academics.’’“It’s exciting to see archery programs in Louisiana schools because it is an inclusive sport and the ALAS program is promoting scholastic achievement as well,’’said Rebecca Triche, executive director of Louisiana Wildlife Federation. “We arepleased to commend the commitment of LDWF and the Louisiana Wildlife and Fisheries Foundation for fostering the program and encouraging the growth in studentparticipation.”Louisiana Wildlife Insider

This photo portrays good browseavailability. There is plenty of browsewithin reach, high diversity and goodcover and habitat.Deer Browse: How Much Does it Take?BY JIMMY ERNST, DMAP CoordinatorFood, water, cover and space are thefour elements of any wildlife habitat. If youwish to manipulate a wildlife population,altering any one of these key features willoften give you the result you are looking for.This applies to improving habitat for a desired species or altering a habitat in orderto reduce a population of an undesirablespecies. If you wish to attract birds to yourback yard, establishing feeders of varioustypes of bird food, providing water in a birdbath, and trees and shrubs for cover is generally all that is needed.Providing quality deer habitat is thesame thing, albeit on a much larger scale.Often, access to a variety of palatable (goodtasting), nutritious food is the limiting factorin deer habitat. For deer, food and cover areoften the same thing. Deer will frequently usethick vegetation that they feed on as escapecover, bedding areas, and fawning cover.Deer are classified as browsers, whichsimply means they feed mostly by nippingSpring/Summer 2021the buds, twigs, leaves and tender newgrowth of vegetation (browse) as opposedto grazers, which feed mostly on grassesclose to the ground. Deer also browse onfungi, lichens, berries and other soft mast.Being a terrestrial animal, deer must haveaccess to browse where they can reach it,typically from the ground up to about sixfeet. No matter how much or what is growing above that vertical limit, if it is out ofreach it is of no value to deer. Even a treefull of the sweetest acorns provide nothingfor deer until the acorns drop to the groundwhere deer can reach them.According to Dr. Steve Demarais ofthe Mississippi State University Deer Ecology & Management Lab, deer need toconsume approximately 6% to 8% of theirbody weight in browse every day. Using theaverage of 7%, a 100 lb. doe needs sevenpounds of browse daily. For a 200 lb. buck,14 pounds. An average 150 lb. deer requires10.5 pounds of browse daily, or 315 lbs. permonth. Nutritional demand fluctuates seasonally such as early spring when bucks arerecovering from the rut and beginning antler growth, or late summer when does arelactating. At these times, deer need additional protein and minerals to satisfy growthrequirements and forage intake may beeven higher. After antlers harden and fawnsare weaned, the need for protein decreasesto a maintenance level and more carbohydrates are needed. This is when hard mastbecomes important. Hard mast in the formof acorns, pecans etc. provides much if notmost of the carbohydrate needs of deer, although browse is always necessary.During the 2020-21 deer season, therewere 672 properties enrolled in DMAP (Tiers1,2,3) averaging 2,161 acres. The averageweight of 7,319 deer reported harvested onDMAP properties during the 2019-20 season was 128 pounds (bucks and does). Fordiscussion purposes, let’s assume that theaverage carrying capacity of these proper-3

LEVELS OF DEER BROWSEPOORBrowse availabilityis poor: little or nobrowse available andpoor habitat.LOWBrowse availabilitylow: some browseavailable but still poorhabitat.MODERATEBrowse availabilitymoderate (butdeclining): trees andshrubs beginning toshade out valuable forbsand other herbaceousplants. Much of thetender new growth is outof reach. Cover is thickand deer have difficultyfreely moving about.GOODBrowse availabilitygood: plenty ofbrowse where deercan reach it. Moderatediversity of browsespecies but goodcover and habitat.4ties is one deer per 40 acres (keep in mindcarrying capacity varies widely across thestate) which amounts to 54 deer per property. Fifty-four average DMAP deer wouldrequire 486 pounds of palatable, nutritiousbrowse every day or 14,580 pounds permonth. That’s a lot of salad!So, what exactly are deer looking forwhen browsing? What is palatable andnutritious? What are the key macronutrients being sought through the plants deerbrowse? There are likely hundreds of species of plants growing on property you huntright now that could theoretically satisfythese requirements. Of these hundreds ofspecies, deer only eat a small percentage of them. Of those they do eat, somespecies, such as blackberry (Rubus spp.)and greenbrier (Smilax spp.) are browsedheavier when the growth is tender and newand often ignored later in the season whenthey turn more woody. In general, tendernew growth is tastier and more nutritiousthan older growth, which tends to becomemore woody later in the season, regardlessof species. Palatability is simply what tastesgood to them. There are many species ofplants in any given habitat that deer justdon’t eat. No matter what habitat you huntin, with the possible exception of coastalmarsh, many of the preferred species deerfeed on can be found throughout Louisiana.Even in the marsh, spoil banks often providemany of the same species that are commonelsewhere. In addition to palatability, deerare seeking three key macronutrients whichinclude crude protein, phosphorous and calcium. All are essential for growth and development. Whether antler or skeletal growth,milk production or overall health, these keymacronutrients play an important role inthe health and productivity of deer.The DMAP Browse Survey form thatwe use to evaluate habitat lists 126 speciesof woody plants that may be encounteredon a survey. Certainly not all of them occuron any one property and there are somespecies encountered that aren’t on the list.When conducting a browse survey in thebest habitats, we may record somewherebetween 30 and 50 different species. Withmoderate browse pressure, 34% - 66% ofthese recorded species would be browsed.These numbers work out to about 10-30different woody species browsed, in goodhabitat. This survey does not include herbaceous species such as annual forbs andgrasses, which provide a valuable component of the nutritional needs of deer, butLouisiana Wildlife Insider

are often short-lived and only available fora brief period of time.Two management techniques that willimprove the condition of deer on a property include manipulating the habitat toprovide enough quality food for the existingdeer herd, or manipulating the deer herd tobalance it with the available habitat. Ideally,every deer on a property would have morethan enough quality food daily to maximizeits potential growth and reproduction. Ifhabitat manipulation is not feasible on alarge scale, herd management is the nextbest tool. Where deer herds are too densefor the existing habitat, DMAP can assistby evaluating the habitat and allowing anincreased harvest of antlerless deer in order to reduce the population to a balancedlevel. Additional antlerless harvest can alsoimprove the sex ratio of bucks and doeswhich is another desirable condition. SeeDeer Management 101 in the 2017 Spring/Summer Louisiana Wildlife Insider life Insider/2017 Spring SummerWildlife Insider.pdf).Providing tasty, nutritious, browse isnot all that complicated, though at times itcan be difficult. Usually, all that is requiredis sunshine. In a closed-canopy forest, lackof sunlight diminishes new growth. Exposing the forest floor to sunlight by removingtrees is the most effective method of generating new growth in a forest. In some cases,there are variables outside of your controlthat may dictate whether or not a timberharvest is feasible. Some properties are located too far from a paper or lumber mill tomake timber harvest economically feasible.At other times, low timber prices preventlandowners from finding a buyer for thetimber, and some properties are just toosmall for a commercial logger to economically harvest. In those cases, creating smallopenings with a chainsaw, specific chemicaltreatment, or heavy equipment will generate at least some quality browse wheredeer can reach it.Managing openings is another methodof providing browse. Allowing openings,fields or food plots to grow up in nativevegetation and mowing or burning everysecond or third year will go a long way ingenerating those pounds of tender vegetation deer need. These areas will also pro-vide bedding and fawning habitat. Rotatinga mowing cycle between two or three fieldsprevents a “boom or bust” cycle of foodand cover in those areas. Managers mustbe vigilant to not let a field go so long thatit becomes too thick to mow and no longer provides the benefits of available newgrowth. Remember, small trees will becomeestablished and must be controlled beforethey are large enough to prevent mowing.Occasionally, a selective herbicide treatment may be necessary to remove them.If you don’t want to give up an entirefield or food plot, consider leaving a bufferof 30-50 feet or more around the edges,allowing the buffer to grow up in nativeplants while you continue planting the remainder of the field/plot. Providing these“soft” edges still generates native browseand cover, leaves some acreage for planting, and may attract deer out of the woodsso you can see them before shooting hoursare over in the evenings! Mowing and fertilizing existing roadside briars or field edgeswill help generate more new growth, providing more browse.Study up on deer browse plants andlearn to recognize them in the woods. Lookfor browse activity and identify those plantsthat deer are utilizing on your land. Below isa list of common preferred browse speciesin Louisiana (Table 1). There are many fieldguides and several QDMA (now NationalDeer Association) publications that canhelp you identify these and help you manage for them.Remember, deer must get everythingthey need where they can reach it - from theground up to about 6 feet, and they needplenty. Next time you are in your huntingwoods, take a look at what, and how muchfood is available from your boots to your hat.See if you can gather a few pounds of tendernutritious vegetation. If you think that wouldbe quite a challenge, you might need somehabitat work. Think about it like this: How farwould a deer have to walk, browsing alongthe way, to obtain the necessary nutrition forone day? In ideal conditions, a deer wouldnot have to venture far to fill his belly, beddown, and do it again tomorrow.COMMONNAMESCIENTIFIC NAMETYPEDeciduous HollyIlex deciduashrubElderberrySambucus cannadensisshrubSumacRhus spp.shrubDogwoodCornus spp.treeAshFraxinus spp.treeElmUlmus spp.treeOaksQuercus spp.treeRed MapleAcer rubrumtreeBlackberry/DewberryRubus spp.vineGreenbrierSmilax spp.vineRed-berriedMoonseedCocculus carolinusvineTrumpet CreeperCampsis radicansvineEvidence of deerbrowse activity ontrumpet creeper(Campsis radicans).Spring/Summer 20215

Louisiana’s 2020 Private LandsConservation ChampionsBY DAVID BREITHAUPT, Farm Bill/Grants Program ManagerCHRIS DOFFITT, Field Botanist/Natural Areas Registry CoordinatorLOWER MISSISSIPPI VALLEY JOINT VENTUREThe Lower Mississippi Valley Joint Venture (Joint Venture) is a voluntarypartnership comprised of 13 state and federal, and four non-government conservation organizations. Established in 1988, the Joint Venture partnershipworks collaboratively on conservation of bird populations and their habitatswithin the Lower Mississippi Valley and West Gulf Coastal Plain/Ouachitas regions in portions of eight states, including Louisiana. It accomplishes this byfocusing on the protection, restoration, and management of birds and theirhabitats in the region. This broad and diverse conservation partnership continues to be an effective and successful forum in which the wildlife conservationcommunity develops and implements a shared vision for habitat conservation.Much of the wildlife habitat in Louisiana is owned and managed by privatelandowners. In fact, 89% of our land base is privately owned. Among the groupof people charged with the stewardship of these lands, several truly stand out.They pour themselves and their resources into their properties and the wildliferesources, which are a public trust, benefit greatly. In 2017 the Lower Mississippi Valley Joint Venture (LMVJV) began to recognize Private Lands Conservation Champions, those who manage their lands in a way that benefits multiplesuites of wildlife and plant communities, while using these activities to engageothers and share what they have learned with members of the public. TheLMVJV is a private, state and federal partnership that exists for the purpose ofsustaining bird populations within an eight state area that includes the Mississippi Alluvial Valley and the Gulf Coastal Plain/Ouachitas Bird ConservationRegions. Two of the three entities to receive this honor in 2020 are Louisianalandowners and we are proud to introduce you to them.Early successional habitatalong a habitat corridor.6Louisiana Wildlife Insider

Native grass managementwith prescribed fire.ED JUSTICEMorehouse Parish, LAMr. Ed Justice spends many days each year “giving back to the land” on his850-acre property in Morehouse Parish, Louisiana. The property is located on a2.5 mile stretch of Bayou Bartholomew, a designated Scenic Stream by LouisianaDepartment of Wildlife and Fisheries. The lower portions of the tract include mature bottomland hardwood as well as reforested areas of the same forest type.Mr. Justice manages a greentree reservoir in this area as well as maintains permanent water in other locations. Other habitat types include mature mixed pine/hardwood, grassland managed as early successional habitat, and shallow waterwetlands. Areas still in agricultural production include a hay meadow and pecanorchard.Natural resource professionals from many partner organizations have beenwelcomed on this property over the last 18 years. The property has been enrolled in the Deer Management Assistance Program for many years, providingvaluable deer harvest data for this region. The NRCS, US Fish and Wildlife Service,Ducks Unlimited, Quail Forever and others have been engaged to provide technical assistance and Mr. Justice has implemented practices such as grassland restoration, prescribed burning, wetland management and invasive species control.Many of these practices not only provide great wildlife habitat, but have beendesigned to provide other benefits, including water quality improvement of BayouBartholomew, wildlife corridors, and establishment of pollinator habitat. Threehundred fifty acres have been restored and permanently protected through theWetlands Reserve Easement Program and the whole property is recognized andenrolled in the Forest Stewardship Program.Goals at the forefront of Mr. Justice’s operation include not only improvingthe habitat for wildlife, but also increasing the diversity of plants and animals thatutilize the property. The active management employed on this property supportshabitat for waterfowl and wading birds as well as forest interior birds, whosehabitat is enhanced by active timber management. Recent efforts to create habitat for the monarch butterfly and other pollinators have enhanced the sameacreage for northern bobwhite. The continuation of these activities will ensurethat Mr. Ed Justice achieves his goal of leaving this piece of property better thanhe found it. Meanwhile, he will continue to gain the most enjoyment from otherscoming to experience the bountiful resources that this property has to offer.Spring/Summer 2021Ed Justice receiving recognition as a Stewardship ForestLandowner, Delivered by John Hanks, LDWF Private LandsBiologist.7

JOHNNY AND KAREN ARMSTRONGLincoln Parish, LADr. Johnny Armstrong and Karen Armstrong have actively managed their 500acre property in Lincoln Parish to maintainan old growth shortleaf pine/oak-hickorywoodland for 13 years. Maintenance andenhancement of this site has been accomplished utilizing a variety of managementtechniques, including prescribed fire, selective herbicide application, and understoryrestoration using native Louisiana seed. TheArmstrong family has personally conductedthe majority of this stewardship work, withoccasional assistance from others to assist with tasks such as prescribed burning.Technical assistance has been providedfrom the Natural Resource ConservationService (NRCS), D’Arbonne Soil and WaterConservation District and other partners.The property is also part of the LouisianaDepartment of Wildlife and Fisheries’ Natural Areas Registry Program.Maintenance of this property is essential and consistent with the goals ofhabitat management on a broad scale forthree primary reasons. First, the shortleafpine/oak-hickory woodland community iscritically imperiled in the state and globallyvulnerable. This community once coveredan estimated 4-6 million acres in Louisiana,but currently less than approximately 10percent remains. Much of the remainingacreage in Louisiana is less than exemplary,and it is rare to find examples that haveboth high quality overstory and a well-developed herbaceous layer. Dr. Armstronghas worked with the U.S. Forest Service tocollect seeds of native Louisiana plants toenhance the understory of the forest onthe property. As a result of the Armstrongfamily’s stewardship activities they havecreated what is perhaps the best exampleof this community type in the state.Secondly, the stewardship activitiescarried out on this property have improvedhabitat for many game and nongame species. Mr. Armstrong’s use of fire to maintain this open woodland ecosystem createsexcellent habitat for wild turkey, northernbobwhite, and white-tailed deer. This shortleaf pine/oak-hickory woodland providesan open understory that is suitable habitatfor many grassland birds and other Speciesof Greatest Conservation Need (SGCN), including grasshopper sparrow, Bachman’ssparrow, and red-cockaded woodpecker.Work is also taking place to protect andenhance the riparian areas associated withthis habitat.Finally, the Armstrong family goes outof their way to share their property and experience to enhance the conservation edu-8cation of the general public and universitystudents. Dr. Armstrong has given severalguest lectures to conservation biology classes at Louisiana Tech University, sharing hisrestoration experience with undergraduatestudents. He has also allowed university faculty and graduate students to conduct research projects on the property, which contribute to an enhanced understanding ofthis unique woodland community and theorganisms that utilize it. Dr. Armstrong willingly shares his restoration expertise withlandowners in the surrounding area, allowing them to benefit from his experience.Brant Bradley, NRCS District Conservationistin Lincoln Parish, summarized this landowner’s focus well, stating, “It’s easy to workwith Dr. Armstrong, because he already hasthe passion and desire to take conservationon his property to the next level.”Photo by Chris DoffittDormant season prescribed fire.Photo by Chris DoffittShortleaf pine/oak hickory woodland.Louisiana Wildlife Insider

Food Plots:Planting vs Natural Vegetationin Pine PlantationsBY MITCH SAMAHA, LDWF BiologistManager - Hunter EducationWe’ve all see them on the huntingshows; huge, lush green food plots, likelyplanted in clovers, alfalfa, or other highlydesirable commercial food plot seed. Thewhite-tails are all over the field, with maturebucks seemingly at every corner of theplot. The many commercial breaks comeon, with the advertisers claiming their XYZseed produces the most attractive, highestprotein, antler-producing plants that willattract multiple trophy bucks from milesaway into your plot during daylight hours;hopefully as you just finish your doughnutsand coffee. If only life was so easy.Places like this do exist. What isn’tmentioned on most of the TV shows isthat much time, effort, and money is spentamending these soils, thereby maintainingtheir peak productivity and attractiveness.Perhaps a corporate outfitter manages theland, or the land is part of a larger habitatthat cooperative landowners have managedtogether for many years, and have a healthydeer herd to show for it. More often thannot, these locations usually have one thingin common; soil quality.So what if someone in a typical pineplantation hunting lease wanted to createthe “perfect” plot? What would developinga one-acre clover plot in a pine plantationSpring/Summer 2021entail? First, they must select a spot andverify with the landowner that they candevelop it for a food plot. On leased landan old logging deck may be an option.They must buy, rent, or borrow a tractor/dozer to remove rotting wood and stumpsfrom the surface to expose the soil; disk orharrow the land to relieve compaction fromthe logging equipment; then conduct a soiltest and use that information to determinehow much lime will be needed to bring thepH to neutral. This can get tricky and costly,depending on access to large equipment orif the lime must be pelletized and spreadby ATV. Then there’s the cost of the seed.Actually, the seed may be the cheapestpart of the entire process, but it must beplanted at the right time and in the rightsoil conditions. Then they fertilize, plant,and hope. By the time the tractor/dozer,diesel, travel time and expenses, lime, seed,and fertilizer costs are tabulated, a huntercould spend conservatively up to 820 fora one-acre clover plot. This figure does notinclude additional weed maintenance asneeded.By contrast, let’s look at a fresh clearcutor older natural opening on the same leasedland and instead of using commercial foodplot seed and all of the aforementionedexpenditures, let’s see how using nativevegetation can compare to the clover plotwith both expense and productivity.First, the logging debris needs to beremoved and a soil test conducted. Forthe native vegetation we wouldn’t need aneutral pH of 6.5-7.0 like clover, alfalfa, orpeas. Therefore, we may only need half theamount of lime required for clover in orderto free up the existing nutrients which arechemically bound by the acidic soil. Lighttillage (disrupting the soil about 1/2” to1-1/2” deep) would incorporate the lime intothe soil and encourage the seeds already inthe soil to germinate the next rainfall. Thesenaturally occurring plants are what the deerin that region already eat and assimilate as“priority foods.” By applying a light fertilizer(about ½ of clover recommendations) weallow these native plants to become muchmore palatable and nutritious than thesurrounding vegetation, thereby increasingthe attractiveness of the plot. Many speciesof native plants in the plot are attractiveat different stages of growth and maturity,providing available browse for an extendedperiod of time. The primary maintenancerequired is to cut the plot to about 8” heightwhen growth exceeds waist-height in orderto encourage regrowth.The average cutover, per acre, can haveas many as 50 different species of plantsthat germinate and grow, most of which areused by wildlife. When the average huntersprays chemicals, tills, and eliminates the“weeds” in his plot preparing to plant hismonoculture (i.e., growing a single plantspecies in a given area), he is replacing avariety of plants that deer and other wildlifeeat regularly and is unknowingly replacingthis unlimited natural salad bar with justone or two species. Imagine going to asalad bar and there would be three choices:mushrooms, lettuce and pickles. Nowimagine a salad bar where the choices areunlimited. Which one would you choose?By managing the forest and creatingnative habitats, desirable managementoutcomes may be achieved faster and moreeconomically when compared to the time,money, and labor put into monocultureplantings.Our Wildlife Division has publications that can assist landowners and leaseholders in identifying deer browse plants. For technical assistance, contact oneof our Private Lands Biologists listed in the Staff Directory.9

10NAIVERSWILESRIIn 1970, the Louisiana Legislature created the Louisiana Natural and Scenic RiversSystem. The system was developed for thepurpose of preserving, protecting, reclaiming, and enhancing the wilderness qualities,scenic beauties, and ecological regimes ofcertain free-flowing Louisiana streams.The Louisiana Department of Wildlifeand Fisheries is responsible for managingand preserving all streams or segmentsthereof that are designated in the state’sScenic Rivers System. Since its creation in1970, this legislation has helped protectapproximately 80 Louisiana streams, rivers,and tributaries, totaling 3,100 miles of waterways throughout the state. As one mightexpect, the streams designated in the Louisiana Scenic Rivers System are as varied asthe landscape of our great state. Examplesof designated streams include large riversystems such as the Ouachita River locatedin north central Louisiana in Morehouseand Union Parishes, to smaller spring fedwaterways like Pushepatapa Creek locatedin Washington Parish. Of those streamscontained within the System, two are designated as historic and scenic rivers. Thesestreams, as the title implies, were designated due to their unique historical status,as well as the scenic characteristics whichthey possess. One of these two streams isBayou Manchac, located south of BatonRouge in Ascension and Iberville Parishes.Long before the enactment of the ScenicRivers Act in Louisiana, this stream playeda significant role in Louisiana’s’ history asa navigable waterbody that was utilized byNative Americans for thousands of years,then by European settlers as early as 1699.Additionally, the Bayou served as a traderoute, especially for the fur and loggingindustries, and as an international borderbetween French and Spanish colonies. Theother stream designated as a historic and5IAISBY CARRIE SALYERS, LDWF BiologistLO ULouisiana Naturaland Scenic RiversSystemIFE & FISHELDS C E NICR1970 - 2020scenic river is Bayou St. John, located withinthe Crescent City of New Orleans.They year 2020 marked the 50th

Spring/Summer 2021 p.20 IN THIS ISSUE P.2 Letter From the Editor P.2 Louisiana Youth Conservation Organization Award P.3 Deer Browse: How Much Does it Take? by Jimmy Ernst P.6 Louisiana's 2020 Private Lands Conservation Champions by David Breithaupt & Chris Doffitt P.9 Food Plots: Planting vs Natural Vegetation in Pine Plantations by Mitch Samaha P.10 Louisiana Natural and Scenic Rivers System