Transcription

NORTH CAROLINA WILDLIFE RESOURCES COMMISSIONWILDLIFE DIVERSITY PROGRAMQUARTERLY REPORT OCTOBER-DECEMBER 2021

Wildlife Diversity Program Quarterly Report for October-December 2021The North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission’s (NCWRC) Wildlife Diversity (WD) Program ishoused within the agency’s Wildlife Management and Inland Fisheries divisions. Program responsibilities principally include surveys, research and other projects for nongame and endangered wildlifespecies. Nongame species are animals without an open hunting, fishing or trapping season.Wildlife Diversity Program StaffDr. Sara Schweitzer, Assistant Chief, Wildlife Diversity Programsara.schweitzer@ncwildlife.org; Wake CountyTodd Ewing, Assistant Chief, Aquatic Wildlife Diversity Programtodd.ewing@ncwildlife.org; Wake CountyScott Anderson, Bird Conservation Biologistscott.anderson@ncwildlife.org; Wake CountyDavid H. Allen, Eastern Wildlife Diversity Supervisordavid.h.allen@ncwildlife.org; Jones CountySierra Benfield – Aquatic Endangered Species Biologistsierra.benfield@ncwildlife.org; Alamance CountyJohn P. Carpenter, Eastern Landbird Biologistjohn.carpenter@ncwildlife.org; New Hanover CountyAlicia Davis, Alligator Biologistalicia.davis@ncwildlife.org; Wake CountyKatharine DeVilbiss, Central Region Aquatic Wildlife Diversity Biologistkatharine.devilbiss@ncwildlife.org; Granville CountyKatherine Etchison, Mammalogistkatherine.etchison@ncwildlife.org; Buncombe CountyDr. Luke Etchison, Western Region Aquatic Wildlife Diversity Coordinatorluke.etchison@ncwildlife.org; Haywood CountyMichael Fisk, Eastern Region Aquatic Wildlife Diversity Coordinatormichael.fisk@ncwildlife.org; Lee CountySarah Finn, Coastal Wildlife Diversity Biologistsarah.finn@ncwildlife.org; New Hanover CountyAndrew Glen, Eastern Region Aquatic Wildlife Diversity Biologistandrew.glen@ncwildlife.org; Alamance County2

Wildlife Diversity Program Quarterly Report for October-December 2021Gabrielle Graeter, Conservation e.org; Buncombe CountyDr. Matthew Godfrey, Sea Turtle Biologistmatt.godfrey@ncwildlife.org; Carteret CountyJeff Hall, Partners in Amphibian and Reptile Conservation Biologistjeff.hall@ncwildlife.org; Pitt CountyDr. Jeff Humphries, Eastern Amphibian and Reptile Biologistjeff.humphries@ncwildlife.org; Orange CountyCarmen Johnson, Waterbird Biologistcarmen.johnson@ncwildlife.org; Craven CountyBrena Jones, Central Region Aquatic Wildlife Diversity Coordinatorbrena.jones@ncwildlife.org; Granville CountyChris Kelly, Western Bird and Carolina Northern Flying Squirrel Biologistchristine.kelly@ncwildlife.org; Buncombe CountyAllison Medford, Piedmont Eco-Region Wildlife Diversity Biologistallison.medford@ncwildlife.org; Montgomery CountyDylan Owensby, Western Region Aquatic Wildlife Diversity Biologistdylan.owensby@ncwildlife.org; Haywood CountyMichael Perkins, Foothills Region Aquatic Wildlife Diversity Biologistmichael.perkins@ncwildlife.org; McDowell CountyTR Russ, Foothills Region Aquatic Wildlife Diversity Coordinatorthomas.russ@ncwildlife.org; McDowell CountyAndrea Shipley, Mammalogist (shared staff with Surveys & Research)andrea.shipley@ncwildlife.org; Nash CountyMike Walter – Aquatic Endangered Species Biologistmichael.walter@ncwildlife.org; Alamance CountyKendrick Weeks, Western Wildlife Diversity Supervisorkendrick.weeks@ncwildlife.org; Henderson CountyLori Williams, Western Amphibian Biologistlori.williams@ncwildlife.org; Henderson CountyNorthern Pine Snake (Jay Ondreicka)3

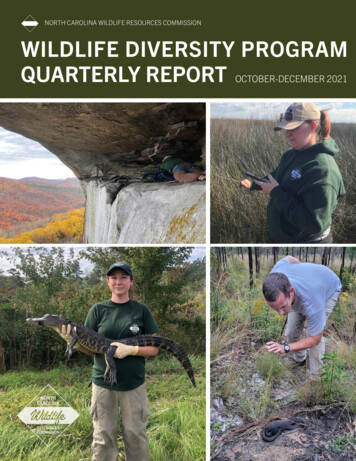

Wildlife Diversity Program Quarterly Report for October-December 2021Table of ContentsBlack Rail Surveys to Start Spring 2022 .5Landowners Are Key Component of NC Birding Atlas’ Future Growth .6Using PIT Tags to Determine Sea Turtle Longevity . 7Two Protected Species Most Encountered During Sandhills Snake Surveys .8Staff Secure Entry to Bat Hibernaculum before Winter Hibernation Begins .9Cameras and Climbers Answer Lingering Questions about Falcons . 10Staff Document Highest Number of New Green Salamander Sites in a Single Season . 12Bog Learning Network holds “Bogs & Brews” virtual meeting in December .14N.C. Partners in Amphibian and Reptile Conservation News . 16Alligator Monitoring Continues in 2021 . 18Stay Connected with the N.C. Wildlife Resources Commissionncwildlife.orgCover photos from top left clockwise: NCWRC Wildlife Technician Clifton Avery sets up a camera on a peregrine falcon nest ledge to monitor nestingactivity (Tom Caldwell); Constance Powell makes notes on vegetation during a scouting trip in November 2021 (Carmen Johnson); NCWRC Technician Mike Martin prepares to capture an Eastern Coachwhip (Jeff Hall); Alligator Biologist Alicia Davis holds a recently tagged alligator during fallsurveys (NCWRC).4

Wildlife Diversity Program Quarterly Report for October-December 2021Black Rail Surveys to Start Spring 2022by Carmen Johnson, Waterbird BiologistThe Waterbird Team recentlybegan planning for surveys ofthe federally threatened Eastern Black Rail that will begin inspring 2022. The Black Rail is asmall, sparrow- sized, secretivemarshbird, and it’s estimated thatonly 40 to 60 pairs remain in thestate. The decline is thought to belargely due to loss of habitat fromsea level rise. Much still needs tobe learned about the subspecies,and research is being carried outin several Atlantic and Gulf Coaststates. The Waterbird Team is collaborating with Dr. Sue McRae atEast Carolina University to learnmore about the species on statelands and how to best manage forthem.Three sites along the NorthCarolina coast have been identified where the species hasbeen detected within the past 10years. Scouting trips were madeto these sites in late 2021, withbiologists looking at vegetation,water level, and microtopographythat meet the needs of the species. Call-response surveys willbe used this spring and summerat points with potentially suitablehabitat in hopes of detecting thebirds and will help the team toplan future work to learn moreabout the species.Constance Powell makes notes on vegetation during a scouting trip in November 2021(Photo: Carmen Johnson)Black Rail (Agami Photo Agency); Potential BlackRail habitat (Photo: Carmen Johnson)5

Wildlife Diversity Program Quarterly Report for October-December 2021Landowners Are Key Component of NC Birding Atlas’ Future Growthby John P. Carpenter, Eastern Landbird BiologistA primary goal of the NorthCarolina Bird Atlas is to engagethe public in conservation work.NCWRC staff expect this willbe accomplished several ways,including increased awarenessof avian conservation by privatelandowners. The importance ofthis group’s participation in theatlas cannot be understated —over 85% of property in NorthCarolina is privately owned. Theability to access non-public landfor the atlas is not only important to increase the data quality,but also provides safer, moreproductive places for agencytechnicians and volunteers towork and demonstrates supportfor the agency’s mission.During this fourth quarter of2021, staff reached out toover 100 landowners andreceived permission to access over 73,000 acres ofprivate property to surveybirds for the benefit of the NCBA.These private landowners represent a vast array of interests: smallsingle-family farms, non-profitorganizations, timberlands andLimited Liability Companies.Staff will continue to conductthis important outreach duringthe life of the project and areoptimistic that the number ofPrivate property in Brunswick County, NC (JP Carpenter)6positive interactions they’vehad with private landowners willcontinue to grow. With a littleluck and some persistence,they hope many of these relationships develop into lifelongopportunities that will benefit allof North Carolina’s wildlife.

Wildlife Diversity Program Quarterly Report for October-December 2021Using PIT Tags to Determine Sea Turtle Longevityby Dr. Matthew Godfrey, Sea Turtle BiologistHow long do sea turtles live?The answer remains a mystery,largely due to the logisticalchallenge of designing a tag thatremains attached to the turtleover years and decades. Newinformation collected by seaturtle nesting beach projectsprovides some insight. In thelast three nesting seasons inNorth Carolina, a combinationof physical and genetic tags hasrevealed that eight loggerheadfemales have been activelylaying eggs in North Carolina forat least 20 years. One turtle wasfirst tagged with a metal flippertag while attempting to nest onCamp Lejeune in June 1995.Metal tags applied to sea turtleshave a relatively high rate offailure after a few years, as is thecase with this turtle, who wasgiven new flipper tags in 2001.In 2003, she was also given apassive integrated transponder(PIT) tag in her left front flipper.PIT tags have a higher retentionrate than metal tags but requirea scanner to be recognized.Her genetic ID has also beendocumented through DNA analysis of a sample of fresh eggshellfrom her nests. These threesources of information combinedhave revealed that this turtlehas continued to nest every fewyears in North Carolina and waslast seen in 2019 while layingeggs on Bald Head Island.Other turtles actively nesting onNorth Carolina beaches includea turtle first tagged in 1998, another in 1999, and five in 2002.The estimated minimum ageof maturity for loggerheads inthe NW Atlantic is 30-35 years,which means these tagged seaturtles are at least 50 years old.More precise estimates at thistime are not possible, becausetagging effort is low in NorthCarolina, and PIT tags wereused only from the early 2000s.However, we expect greater understanding of sea turtle longevity as tagging efforts and geneticsampling continue.An adult female loggerhead nesting on Onslow Beach in Camp Lejeune, North Carolina(Dr. Matthew Godfrey)7

Wildlife Diversity Program Quarterly Report for October-December 2021Two Protected Species Most Encountered During Sandhills Snake Surveysby Dr. Jeff Humphries, Eastern Amphibian and Reptile BiologistThis year ended the seventhyear of a mark-recapture studyof selected snake species onthe Sandhills Game Land inScotland and Richmond Counties. The purpose of this studyis to gather information aboutpopulation size, populationstatus (declines or increasesover time), movements, growthand other aspects of the natural history of each species.Staff are targeting a mixture ofsnakes perceived as “rare” and“common” in the state. Surveymethods include driving roads,walking habitat, and checking artificial cover throughout the year.Snakes are marked with PIT tagsand scale marking. Over sevenyears, biologists have encountered 541 individuals of the sixspecies targeted. Of note is thevery small number of recaptures ofany of the species. Differences inroad mortality among the differentspecies is becoming evident. Interestingly, two of the species thatare considered Species of Greatest Conservation Need (NorthernPinesnake and Eastern Coachwhip) have been encountered themost during this study. This doesnot mean these species are notin need of conservation, but thehigh encounter rate specifically inthe Sandhills is encouraging andlikely a result of large areas ofwell managed habitat on the gameland. This study will continue forat least three more years anddata will then be compiled andanalyzed to provide a baselinefor research and monitoring.Northern Pine Snake (Jeff Hall)Eastern Coachwhip (Jay Ondreicka)Sandhills Snake Encounters orn SnakeTotal EncountersSouthernHognoseEasternHognoseTotal CapturesNorthernPinesnakeEasternCoachwhipRoad MortalitySnake encounters over seven years in the Sandhills of North Carolina, including recaptures and road mortality.8

Wildlife Diversity Program Quarterly Report for October-December 2021Staff Secure Entry to Bat Hibernaculum before Winter Hibernation Beginsby Katherine Etchison, MammalogistEach year, NCWRC staff visitan Avery County mine that servesas an important hibernaculum toseveral bat species to secure thesite against unauthorized entry.Bats are sensitive to disturbancewhen hibernating, especiallyspecies susceptible to WhiteNose Syndrome, so preventingunauthorized entry during winteris key. Multiple trips were madeto the mine during October andNovember to make necessaryrepairs before bats returned tothe mine to hibernate. A portionof the security fence was partially buried from a small landslideand further compromised byvandals, so additional posts wereinstalled, and the fencing was removed and replaced. Weak areasof the security fence were alsorepaired, and a damaged lockwas replaced. A thorough searchof the area was performed toensure no other points of entryhad been breached. Securitycameras in the area were alsomaintained, and photos wereturned over to law enforcement.A hibernaculum survey will beperformed in January to monitorhibernating bats in the mine.Conservation Technician, Joe Tomcho, Western WildlifeDiversity Supervisor, Kendrick Weeks, and Wildlife Diversity Technician, Kyle Shute, repair the bat gate inside anAvery County mine. (Katherine Etchison)Western Wildlife Diversity Supervisor, Kendrick Weeks, repairsthe security fence surrounding an Avery County mine.(Katherine Etchison)9

Wildlife Diversity Program Quarterly Report for October-December 2021Zachary Lesch-Huie of TheAccess Fund and MikeReardon of the CarolinaClimbers Coalition point tothe ledge where peregrinefalcons attempted to nest atBig Lost Cove Cliff in AveryCounty in 2021.Lynn Willis of High South CreativeCameras and Climbers Answer Lingering Questions about Falconsby: Christine Kelly/ Western Bird and Carolina Northern Flying Squirrel BiologistEvery year, biologists monitorperegrine falcons nesting oncliffs by watching them from afarthrough spotting scopes. To get acloser look, the NCWRC partnerswith rock climbers to access theledges. These brief but exciting visits often answer a lot ofquestions staff couldn’t answerfrom hours of watching throughscopes. For instance, the climbers can see if the nest ledge isprotected from the elements byan overhanging roof and if it isinaccessible to mammalian predators. Prey remains found duringthese excursions tell biologistsabout the birds’ diets. At Big LostCove, climbers from The AccessFund and Carolina Climbers Coalition discovered remains of bluejays and woodpeckers. Theyalso found a rodent latrine in anadjacent ledge.Climbers also help deploycameras in nest ledges. In October, the Appalachian Mountain Rescue Team retrieved twocameras that were installed in anest ledge in Rutherford County back in January and set upnew cameras. The goal was tobetter understand why this sitesuffers chronic nest failure. Theyfound a few things: southernflying squirrels can access thisledge, which could result in eggpredation. The falcons neverlaid eggs at this ledge in 2020despite spending lots of timethere. Though falcons mostlyhunt birds, they will prey on batsand other mammals opportunistically. On two occasions, a falconwas pictured clutching a bat forits early morning breakfast. Thisalso brings to mind the questionof whether there are enoughprey in the Hickory Nut Gorgefor nesting pairs to raise a family.And most surprising was cameracontinue on next page10

Wildlife Diversity Program Quarterly Report for October-December 2021Joel McCombs of the Appalachian Mountain Rescue Team perchesoutside the peregrine ledge at Chimney Rock (Corey Winstead)A male peregrine falcon (foreground) tidies the “nest scrape” whilethe female (background) looks on. Notice the blue-gray and whitecoloring and smaller size of the male compared to the brownish-gray and cream coloring of the larger femaledocumentation of a subadultfemale falcon in late winter andearly spring that observers neversaw from their spotting scopes.An adult female replaced herlater in the season.The remoteness of most ofthe peregrine falcon nest ledgesin the mountains poses a challenge for powering camerasand relaying images during thebreeding season. This fall, theCarolina Climbers Coalition andWhat is causing chronic nest failureamong peregrine falcons?A camera deployed on a nest ledgein Rutherford County providedbiologists with at least one possiblereason why this site suffers chronicnest failure: southern flying squirrels can access this ledge, whichcould result in egg predation.NCWRC Wildlife Diversity Technician Clifton Avery deployeda camera in another peregrinenest ledge. This camera willtransmit footage wirelessly toa home camera on the ground.The resident pair of falconsshowed up on camera immediately, and the male set to worksmoothing the nest “scrape”while his mate looked on.Nest cameras are only usefulat cliffs where the falcons returnto the same nest ledge eachyear. At some cliffs, they rotatebetween ledges, making it aguessing game as to where todeploy a camera. Where nestcameras are a good option,biologists hope they will provideinsight into causes of nest failure, turnover of individuals, andmore. They can be the eyes andears of biologists, and hopefullysave staff time and thousands ofmiles of driving.11

Wildlife Diversity Program Quarterly Report for October-December 2021A hatchling Green Salamander active on wet, bare rock. Note the bluecoloring, as it can take many months to develop normal coloration.Ben DaltonStaff Document Highest Number of New Green Salamander Sites in aSingle Seasonby Lori Williams, Western Amphibian BiologistIn fall 2021, Wildlife Diversitystaff and a longtime volunteerconducted rock outcrop surveys for state threatened GreenSalamander that occupies theBlue Ridge Escarpment of western North Carolina (Henderson,Transylvania, Jackson and Macon counties). They completedthe most surveys ever in a fallseason for the species (n 743) at462 individual rock outcrop sitesand documented the highestnumber of new sites in a singleseason (n 41). Out of the 743surveys, 237 had at least oneGreen Salamander for a successrate of 31.9%, almost identical toefforts in fall 2020 (736 surveys,32.3% success).As an important indicator ofnest success, at least one hatch-ling Green Salamander wasdocumented in 22 surveys at19 individual rock outcrop sites.At just one site, they observedat least nine hatchlings on therock surface and nine othersclimbing shrubs by their nestrocks at heights of more than 12feet above ground. Other habitatused by hatchlings, yearlings,older juveniles and adultscontinue on next page12

Wildlife Diversity Program Quarterly Report for October-December 2021included not only the usual rockcrevices and out in the open onbare rock but also on the rocksurface under rock tripe and withinmoss, under bark pieces or othernatural cover on top of rocks, andon mature trees and shrubs adjacent to rock outcrops.Trees, and even tall shrubslike rhododendron and mountainlaurel, next to rock outcrops, arecritical for providing shade andkeeping humidity and moisture atsuitable levels for salamanders. Itis established in literature the roletrees and shrubs play for GreenSalamanders, which are highlyadapted to climb them, in termsof aiding dispersal and providingrefugia and foraging opportunities,but biologists’ actual observationof this unique habitat use is notvery common.In fall surveys, staff attempted tofocus more on looking in trees andshrubs than in years past. In addition to hatchlings at several sites,they found four adults and olderjuveniles climbing trees, 6-8 feethigh and up. On one occasion, anadult Green Salamander was observed 7 feet high, and 45 minuteslater, it had climbed to over 12 feethigh (and still climbing).Staff will continue these criticalpopulation monitoring and inventory surveys for Green Salamanders yearly. Going forward, theywill focus especially on learningmore about habitat use by all ageclasses, hatchlings through adults.An adult Green Salamander climbing 12 feet high (and still going) up a magnolia tree(Ben Dalton)When moist, rock tripe provides excellent cover and camouflage for this GreenSalamander (red arrow). (Ben Dalton)13

Wildlife Diversity Program Quarterly Report for October-December 2021Bog Learning Network holds “Bogs & Brews” virtual meeting in Decemberby Gabrielle Graeter, Conservation Biologist/HerpetologistThe Bog Learning Network(BLN) is a consortium of scientists and land managers workingto advance the restoration andmanagement of Southern Appalachian Bogs. It provides aforum for sharing information andexperiences about bog management and conservation and helpsbog managers find resourcesand assistance. Strategies ofthe BLN include coordinatingprotection efforts for SouthernAppalachian wetlands, supporting on-the-ground conservation,facilitating and providing learningopportunities, and increasingBLN membership and outreach.Annual learning opportunitiesthat the BLN offers include fieldtrips and “work-and-learn” workdays, whereby a bog managergets much needed assistancein the field with a project, andsimultaneously the participantslearn about bogs and variousbog management techniques.When the pandemic beganin early spring 2020, the BogLearning Network’s (BLN) annualmeeting, scheduled for April, waspostponed indefinitely. The BLNsteering committee waited untillate summer 2021 to see if anin-person meeting would be possible but concluded that a virtualmeeting would be the safest wayto connect with members. There-14fore, the BLN Steering Committee, on which NCWRC’s GabrielleGraeter serves, planned the December 2021 “Bogs and Brews”virtual meeting.The December 2021 virtualmeeting was relatively short andheld at the end of the day sopeople could have a “brew” oftheir choice (tea, coffee, beer,etc.) and sit back and enjoy themeeting without worrying aboutgetting “Zoom fatigue.” Themeeting included updates fromthe BLN leadership and severalsub-committee leaders, followedby a variety of interesting talks– illegal turtle collection, theinfluence of site history on bogturtle abundance, communityclassification of Kentucky’s bogs,and the use of native ferns as abiological control for an invasiveplant species. During a sessiontitled “Postcards from the Field,”several BLN members sharedslides and talked for a fewminutes each about an excitingcontinue on next pageFigure 1. In fall 2021, a Bog Learning Network Work-n-Learn workday was heldwith participation limited to 10 people for safety due to the pandemic. Here arethe participants learning about the history of the wetland and property as wellas the objectives for the workday.

Wildlife Diversity Program Quarterly Report for October-December 2021project. The meeting was a greatsuccess – 111 people registeredand at least 62 people attendedthe meeting live! Although it wasnot as good as meeting in person, the virtual format allowedthe BLN leadership to sharesome important BLN updates,hear about recent work by several members, and connect withmany of the BLN members.A screenshot of participants in the December 2021 virtual Bog LearningNetwork’s “Bogs and Brews” meeting.How YOU Can Support Wildlife Conservation in North CarolinaWhether you hunt, fish, watch, or just appreciate wildlife, you can help conserve North Carolina’s wildlifeand their habitats and keep North Carolina wild for future generations to enjoy.How? It's as easy as 1, 2, 3.123Donate to the Nongame and Endangered Wildlife Fund by checking Line No. 30 on your N.C. StateTax Form.Purchase a Wildlife Conservation Plate, which features an illustration of a PineBarrens Treefrog, for 30, with 20 going to the agency's Nongame andEndangered Wildlife Fund.Donate to the Wildlife Diversity Endowment Fund, a special fund where the accrued interest — notthe principal — is spent on programs that benefit species not hunted or fished. ncwildlife.org/donate15

Wildlife Diversity Program Quarterly Report for October-December 2021N.C. Partners in Amphibian and Reptile Conservation Newsby Jeff Hall, Partners in Amphibian and Reptile Conservation BiologistDuring this final quarter of2021, field highlights includedupland snake surveys, NeuseRiver Waterdog surveys, andplacement of monitoring devices. Upland snakes encounteredduring this quarter includedEastern Diamondback Rattlesnake, Carolina Pigmy Rattlesnake, Southern Hognose Snake,Northern Pine Snake and EasternCoachwhip. Surveys were conducted at numerous sites alongthe Coastal Plain and into theSandhills. Additionally, through acontact with a private landowner in Pender County, staff wereable to catch and photograph anEastern Coral Snake. Records forthis species are very few and farbetween so this was particularly rewarding. NeuseRiver Waterdog surveyswere completed atseven Craven Countyhistorical sites. Unfortunately,the salamanders were onlydetected at one of the sevenlocalities. Numerous automatedaudio recording devices (akaFrogloggers) were deployed fordetection of winter-breeding anurans such as Ornate Chorus Frogand Gopher Frog. Trail cameraswere installed to observe behaviors of rattlesnakes, most notablytargeting the Eastern Diamondback Rattlesnake. Analysis ofautomated data will be ongoingin future quarters.Pine Barrens Gentian from Onslow Countyblooms in the fall in open grassy habitat,such as is found in longleaf pine savannas(Jeff Hall)Eastern Coral Snake found in PenderCounty (Jeff Hall)16

Wildlife Diversity Program Quarterly Report for October-December 2021During upland snakesurveys in the CoastalPlain and the Sandhills, staff encounteredseveral species, including (top left) EasternDiamondback Rattlesnake, Eastern Coachwhip (middle left)All photos by Jeff HallNeuse River Waterdogs (left) found at only one of seven historical sites in Craven County (right)17

Wildlife Diversity Program Quarterly Report for October-December 2021Alligator Monitoring Continues in 2021by Alicia Davis, Alligator BiologistIn spring 2017, NCWRC initiated a new marking and datacollection protocol for all alligators handled by agency staffand permitted external handlers,including Alligator Control Agents,Jurisdictional Alligator Handlers,and scientific researchers*.First, every handled alligator isscanned to determine if it hasalready been tagged. Handlersmark all new captures withan internal Passive IntegratedTransponder (PIT) tag, collect twoThese data are of greatbenefit to the agency’s alligatorconservation efforts. Equippedwith this information, biologistsare able to learn more aboutgrowth rates and movements ofindividuals at different life stages, evaluate the effectiveness ofvarious management practices,and identify communities thatcould benefit most from outreach programs with guidanceon coexisting with alligators.tissue samples from tail scutes,determine sex, take body sizemeasurements, and record GPScoordinates of locations of capture and release. Measurementsand locations are recorded for allrecaptured individuals. To date,800 wild alligators have beencaptured, marked and released inNorth Carolina using this method.Data were collected from 283 alligators in 2021, 57 of which wererecaptured individuals that hadbeen marked previously.continue on next page225200175Number of tureNew2018Nuisance 021Surveys/ResearchWild Alligators Captured, Marked, and Released in North Carolina by Year (2017-2021)* Scientific researchers include Dr. Stephen Dinkelacker, Framingham State University and Dr. Scott Belcher, NC State University18

Wildlife Diversity Program Quarterly Report for October-December 2021In addition to data collectionfrom live alligators, NCWRCbegan collecting data from alldead alligators in 2017. To date,data have been collected from61 dead alligators, 53 of whichwere found dead. Of the 13alligators that were found deadin 2021, three were hit by motorvehicles, one was inadvertently captured and drowned in acommercial pump, six appearedto have been illegally killed, andthe cause of death for threealligators was not apparent. Oneof the six poached alligatorsity or euthanized. Two alligatorswere euthanized in 2021 for thesereasons. Within the range of natural alligator occurrence, one additional alligator was euthanized in2021 due to severe injuries from amotor vehicle strike.Femurs and other tissuesamples were also collected fromeach dead alligator. In 2022,stored alligator femurs will besent to a laboratory where growthrings in bone cross-sections willbe analyzed in an attempt to ageeach individual.was found shot in a remote areawhere it had been relocated sixmonths prior.In rare situations in which alligators are found in locations faroutside of alligator range, agency staff must assume that thoseindividuals have been illegallykept in captivity. Due to concernsabout potential disease introductions and/or habituation to beingfed by humans, those individualsare not released into habitats thatsupport wild alligator populations;rather, those individuals must betransferred to permanent captiv-Alligators Mortalities in North Carolina by year (2017-2021)Mortality type2017New20182019Recap NewRecap New2020Recap 121308Found Dead50903018512153Total50904120615161NCWRC staff mark and collect data from all hatchlings found at nest sites.(Alicia Davis)19

housed within the agency's Wildlife Management and Inland Fisheries divisions. Program responsi-bilities principally include surveys, research and other projects for nongame and endangered wildlife species. Nongame species are animals without an open hunting, fishing or trapping season. Dr. Sara Schweitzer, Assistant Chief, Wildlife Diversity .