Transcription

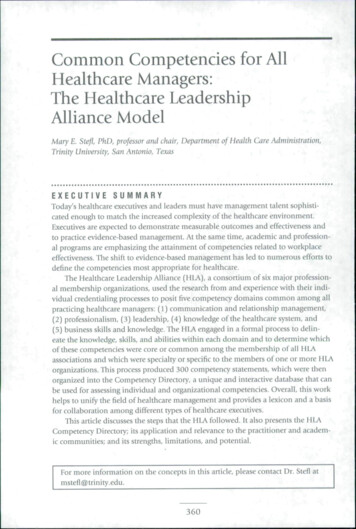

Common Competencies for AllHealthcare Managers:The Healthcare LeadershipAlliance ModelMaryE. Stefl, PhD, professor and chair. Department of Health Care Administration,Trinity University, San Antonio, Texas- .EXECUTIVESUMMARYToday's healthcare executives and leaders must have management talent sophisticated enough to match the increased complexity of the healthcare environment.Executives are expected to demonstrate measurable outcomes and effectiveness andto practice evidence-hased management. At the same time, academic and professional programs are emphasizing the attainment of competencies related to workplaceeffeaiveness. The shift to evidence-based management has led to numerous efforts todefine the competencies most appropriate for healthcare.The Healthcare Leadership Alliance (HLA), a consortium of six major professional membership organizations, used the research from and experience with their individual credentialing processes to posit five competency domains common among allpracticing healthcare managers: (1) communication and relationship management,(2) professionalism, (3) leadership, (4) knowledge of the healthcare system, and(5) business skills and knowledge. The HLA engaged in a formal process to delineate the knowledge, skills, and abilities within each domain and to determine whichof these competencies were core or common among the membership of all HLAassociations and which were specialty or specific to the members of one or more HLAorganizations. This process produced 300 competency statements, which were thenorganized into the Competency Directory, a unique and interactive database that canbe used for assessing individual and organizational competencies. Overall this workhelps to unify the field of healthcare management and provides a lexicon and a basisfor collaboration among different types of healthcare executives.This article discusses the steps that the HLA followed. It also presents the HLACompetency Directory; its application and relevance to the practitioner and academic communities; and its strengths, limitations, and potential.For more information on the concepts in this article, please contact Dr. Stefi atmsten@trinity.edu.360

COMMON COMPETENCIES FOR ALL HEALTHCARE MANAGERSPeter Drucker (2002) has said thatlarge healthcare institutions may bethe most complex in human history andthat even small healthcare organizations are barely manageable. Some timehas passed since Drucker's observation,but the complexity of healthcare organizations, along with the demands onmanagers and leaders, has not diminished in any way. Today, executives inall healthcare settings must navigate alandscape influenced by complex socialand political forces, including shrinkingreimbursements, persistent shortages ofhealth professionals, endless requirements to use performance and safetyindicators, and prevailing calls for transparency. Further, managers and leadersare expeaed to do more with less.Since 1999, the Society of Healthcare Strategy and Market Developmentand the American College of HealthcareExecutives have been producing Futurescan, a compendium of healthcare trendsand projections for the next five years. InFuturescan 2008, the publication's executive editor, Don Seymour, reflected onthe past ten years in healthcare:society appears to be sending a clear,overarching message to the nation'shospitals: Take care of more peoplewho have growing expectations andmore complex medical needs v -hileproviding increasingly sophisticatedcare with relatively fewer resources.The questions now become. Havemid- and senior-level managers beenkeeping pace with changing demands?Are healthcare academic programs attracting sufficient numbers of studentsand adequately preparing them to operate effectively in this dynamic environment? These concerns were the focus ofthe 2001 National Summit on the Future of Fducation and Practice in HealthManagement and Policy. Principallyfiinded by the Robert Wood JohnsonFoundation, this conference broughttogether practitioners, policymakers,and educators to examine the effectiveness of healthcare administration andthe role of academic preparation andcontinuing professional developmentin tackling the current and future challenges of healthcare delivery.The Summit's deliberations focusedon evidence-based approaches (seeKovner 2001 ) to developing management talent, including how to measurethe outcomes of health managementeducation (Griffith 2001) and howto determine whether administrationstudents and practicing managers hadacquired the competencies necessary toperform effectively in their roles.THE COMPETENCY MOVEMENTThe emphasis on measurable outcomesand competencies did not happenovemight. The widespread acceptanceof evidence-based medicine was anatural precursor to an evidence-basedapproach to healthcare management(Kovner and Rundall 2006). Also, thedevelopment and promotion of competencies for graduate medical education(Batalden et al. 2002) set the stage forhealthcare administration.In an environment of escalated publicdemand, it is only lógica! to questionthe competence of healthcare leaders and managers. As noted in Griffith(2007), the increased difficulty of running a healthcare organization has ledto the need for managers with moresophisticated capabilities.361'''

OF HEALTHCAREMANAGEMENT53:6NOVEMBER/DECEMBER2008More broadly, higher educationhas struggled with the issue of competency-based education for some time(Calhoun et al. 2002; Westera 2001).The main idea behind this initiative is todesign curricula based on the roles thatgraduates will assume after completing their degree and to incorporate thespecific knowledge, skills, and abilities(KSAs) that future employees will need.Efforts to promote competencies havebeen undertaken in numerous fields,including public health (Council onLinkages Between Academic and PublicHealth Practice 2001) and the healthprofessions (IOM 2003). The controversial Spellings report (issued in 2006 bythe Secretary of Education's Commission on the Future of Higher Educationconvened by U.S. Secretary of EducationMargaret Spellings) pushes universities nationwide to measure studentoutcomes and then make these resultsavailable to the public.that their competency models are tiedwitb the realities and needs of healthcare management practice. However,little evidence shows a link betweenactual performance and competencyattainment (Bradley 2003), an area ofinquiry tbat clearly needs more attention as competency models continue todevelop.Aside from this work in academia,the National Center for Healthcare Leadership has expended considerable effortin creating a competency model that canbe applied to professional developmentand to academic programs (Calhounet al. 2004; NCHL 2005). In addition,many healthcare associations have usedexpert opinion and job analysis surveysto delineate the KSAs that form the basisfor their credentialing exams. However,these KSAs were not usually shared withtbe broader healthcare managementcommunity.To meet the needs of healthcareadministration, a number of university programs have developed a set ofcompetencies (e.g., Cherlin et al. 2006;Shewchuk, O'Connor, and Fine 2005;2006; White, Clement, and Nayar 2006)or competency models (e.g., Campbellet al. 2006) for their students. A reviewof these efforts is beyond the scope ofthis article, but note that these variousprograms typically use a similar process for developing their competencies:(1) existing competency literature isreviewed, (2) subjea matter experts(either faculty or practitioners) are approached to provide depth and contentvalidity, and (3) a survey of practitioners is condurted. In other words,academic programs take steps to ensureTHE H E A L T H C A R ELEADERSHIP ALLIANCEThe Healthcare Leadership Alliance(HLA) is a consortium of major professional associations in the healthcarefield: American College of HealthcareExecutives (ACHE); American College of PhysicianExecutives (ACPE); American Organization of NurseExecutives (AONE); Healthcare Financial ManagementAssociation (HFMA); Healthcare Information and Management Systems Society (HIMSS); and Medical Group Management362

COMMON COMPETENCIES FOR ALL HEALTHCARE MANAGERSAssociation (MGMA) and its educational affiliate, the American College ofMedical Practice Executives (ACMPE).Together, these associations representmore than 100,000 management professionals.I 'In response to concerns about theadequate preparation of healthcaremanagers and administrators, the HLAconvened the Competency Task Force toexamine the credentialing and certification processes of its member organizations. First meeting in late 2002, theTasii Force was composed of a representative from each organization' and afacilitator (this author). The Task Forcewas charged with a straightforwardresponsibility: Determine if there weremanagement competencies shared by allmembers of the HLA organizations. Ifso, the Task Force would determine howthese competencies could be used toadvance the field.Reviewing the Credentialing andCertification ProcessesI ask Force work began with an exchangeof information regarding each association's credentialing and certificationprocesses. Five of the six organizationshad well-established processes, whileAONE was considering launching itsown certification program. Certification programs are designed to ensurethat individuals in a professional position meet the basic educational, skill,and/or experiential requirements oftheir respective profession (Raymond2001 ). Thus, credentialing or certification exams should be job-related andshould be designed to test whether theprofessional possesses the KSAs essentialfor his or her job. For large organizations, certification exams are typicallyobjective, with questions constructedfollowing the job analysis studies.Four associations (ACHE, HFMA,HIMSS, and ACMPE) used wellestablished psychometric processes(job analysis surveys or role delineationstudies, review by subject matter experts,and content analysis) to determinethe KSAs for their certification exams(NCCA 2007). All engaged reputablepsychometric firms to ensure the reliability and validity of their processes.The ACPE's certification process wasslightly different from that employedby the rest of the group. Following anon-site tutorial session, ACPE candidateswere tested by faculty experts using anin-basket exercise and requiring a verbalpresentation. All associations' certification exams were discriminatory; firsttime pass rates ranged from 60 percentto 85 percent (Stefl 2003a).In general, the certification processesof the HLA organizations were intendedto provide early careerists an opportunity to demonstrate their competence. Atthe time of the Competency Task Force'sreview of KSAs, most HLA associations(except AONE) offered a fellowshipstatus for those with more senior-Ieve!accomplishments and contributions.Most associations (except HIMSS)awarded the Fellow status only after thatmember had attained certification andthe requisite competencies. Thus, theTask Force's review excluded the fellowship processes.Identifying Common CompetenciesThe extensive review of the credentialingand certification processes of the HLA363

JOURNAL OF HEALTHCARE MANAGEMENT 5 3 : 6NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 2 0 0 8members revealed a number of overlapping and complementary competencies.The Task Force determined that theseKSAs clustered into five competencydomains that were common among themembership of all six associations (Stefl2003a):management, (c) organizational dynamics and governance, (d) strategicplanning and marketing, (e) information management, (f ) risk management, and (g) quality improvementIn keeping with the current focus onoutcomes and evidence-based management, these five domains were viewedas common competencies or competency domains. While "competency"can be defined in a variety of ways, theTask Force adopted a definition fromRoss, Wenzel, and Mitlyng (2002):Competencies are clusters that "transcend unique organizational settingsand are applicable across the environment. "That is, the domains identified by the Task Force are generic anddemonstrable.1. Communication and RelationshipManagement: The ability to communicate clearly and concisely withinternal and external customers,to establish and maintain relationships, and to facilitate constructiveinteractions with individuals andgroups2. Leadership: The ability to inspireindividual and organizational excellence, to create and attain a sharedvision, and to successfully managechange to attain the organization'sstrategic ends and successful performance3. Professionalism: The ability to alignpersonal and organizational conduct with ethical and professionalstandards that include a responsibility to the patient and community,a service orientation, and a commitment to lifelong learning andimprovement4. Knowledge of the Healthcare Environment: The demonstrated understanding of the healthcare system and theenvironment in which healthcaremanagers and providers function5. Business Skills and Knoivledge: Theability to apply business principles,including systems thinking, to thehealthcare environment; basic business principles include (a) financialmanagement, (b) human resourceThe Task Force viewed these competency domains as interdependent(see Figure 1). Because leadershipcompetencies are central to a healthcareexecutive's performance, the Leadershipdomain anchors the HLA model. Allother domains draw from the Leadership area, but the other competenciesalso feed and inform leadership. InFigure 1, the two-way arrows outside thecircles indicate that the other four domains draw from each other and shareoverlapping KSAs.The identification of these fivedomains sends a powerful messageto the healthcare field: Healthcaremanagers in a wide range of positionsand settings share a common body ofknowledge and a common lexicon.Such a message can break down barriers between various health management professionals, provide a stronger364

practicing healthcare managers: (1) communication and relationship management, (2) professionalism, (3) leadership, (4) knowledge of the healthcare system, and (5) business skills and knowledge. The HLA engaged in a formal process to delin-eate the knowledge, skills, and abilities within each domain and to determine which