Transcription

Analyzing the Russian Way of WarEvidence from the 2008 Conflict with GeorgiaLionel BeehnerLiam CollinsSteve FerenziRobert PersonAaron BrantlyMarch 20, 2018A Contemporary Battlefield Assessmentby the Modern War Institute

Analyzing the Russian Way of War: Evidence from the 2008 Conflict with GeorgiaContentsAcknowledgments . 1Executive Summary . 3Introduction . 9Chapter I – History of Bad Blood. 13Rose-Colored Glasses . 16Chapter II – Russian Grand Strategy in Context of the 2008 Russia-Georgia War . 21Russia’s Ends . 22Russia’s Means . 23Russia’s Ways . 25Pragmatic Accommodation, 2000–2003 . 26Soft Balancing, 2003–7 . 27Hybrid Balancing, 2007–17 . 28“Hybrid Warfare” Explained. 30Chapter III – The Five-Day War . 35Invasion . 38Day 1—August 7, 2008: A Ground Invasion . 38Day 2—August 8, 2008: The Battle of Tskhinvali . 41Day 3—August 9, 2008: The Second Battle of Tskhinvali . 43The Western Front . 44Day 4—August 10: A Disorderly Retreat . 45Day 5—August 11: The Battle for Gori . 46Military Lessons Learned from the 2008 War. 49Russia . 49Georgia. 54Chapter IV – Russia’s Use of Cyberattacks and Psychological Warfare in Georgia . 59Bits and Bytes . 60A Tool for Psychological and Information Warfare. 65Chapter V – Lessons from Georgia and Ukraine . 69The Situation in Ukraine. 70Chapter VI – Recommendations and Key Takeaways . 77Bibliography. 83

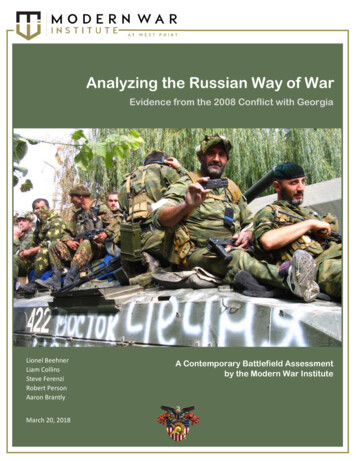

Analyzing the Russian Way of War: Evidence from the 2008 Conflict with GeorgiaAcknowledgmentsResearch for this report was carried out in May–June 2017 by cadets and faculty of the US MilitaryAcademy at West Point in the Republic of Georgia. The authors held conversations with a number of seniormilitary leaders, cyber Ministry of Defense (MoD) officials, Georgian politicians—both in power and in theopposition—activists, journalists, and academics in the region. The group toured and surveyed the 2008battlefield, conducting a “staff ride” of key battles in Gori; the administrative boundary line (ABL) of SouthOssetia next to Tskhinvali; the ABL of Abkhazia; and of course, Tbilisi, the capital. The authors would liketo thank the following people, who either briefed the group, provided input to its findings, or assisted inthe organization of this contemporary battlefield assessment: John Mearsheimer, Wayne Merry, MichaelKofman, Jeffrey Mankoff, Anastasia Shesterinina, Thomas Sherlock, Brent Colburn, Stephen Blank, NataliaAntelava, Eric Barrett, Timothy Blauvelt, Robert Hamilton, Christopher Drew, Garrick Harmon, GarrettTrott, Andrew Horsfall, Andrea Keerbs, Giga Bokeria, Irakli Beria, Tekla Kalandadze, George Ugulava, ShotaUtiashvili, Goka Gabashvili, David Darchiashvili, Koba Kobaladze, and all the members of Georgia’s armedforces who met with the group. From West Point, the authors would like to thank John Amble, JakeMiraldi, Sally White, Scott Woodbrey, Doreen Pasieka, and Alec Meden for their logistical, editorial, andadministrative support. Research for this report was provided by the following cadets: Garrett Dunn,Alexander Gudenkauf, Seth Ruckman, Daniel Surovic, and James White. A final thanks goes out to thegenerosity of Vincent Viola.Cover image: Soldiers of the Russian Vostok Battalion in South Ossetia, August 2008 (Image credit: YanaAmelina)1

Analyzing the Russian Way of War: Evidence from the 2008 Conflict with GeorgiaExecutive SummaryIn the dog days of August 2008, a column of Russian tanks and troops rolled across the Republic ofGeorgia’s northern border and into South Ossetia, sparking a war that was over almost before it began.The war, while not insignificant, lasted all of five days. The number of casualties did not exceed onethousand, the threshold most political scientists use to classify a war, although thousands of Georgianswere displaced. By historical comparison, when Soviet tanks entered Hungary in 1956 and Afghanistan in1979–89, the fatalities totaled 2,500 and roughly 14,000 respectively. 1 The Russia-Georgia conflict was alimited war with limited objectives, yet it was arguably a watershed in the annals of modern war. It markedthe first invasion by Russian ground forces into a sovereign nation since the Cold War. It also marked abreakthrough in the integration of cyberwarfare and other nonkinetic tools into a conventional strategy—what some observers in the West have termed “hybrid warfare.” Finally, and perhaps most importantly,it provided a stark preview of what was to come in Ukraine in 2014. Russian “peacekeepers,” includingunmarked Russian special forces—or Spetsnaz—stationed in the region carried out an armed incursion.That is, Russia used separatist violence as a convenient pretext to launch a full-scale multidomain invasionto annex territory, a type of aggression that many analysts in the West thought was a relic of the twentiethcentury.The 2008 Russia-Georgia War highlights not a new form of conflict but rather the incorporationof a new dimension to that conflict: cyberspace. Where states once tried to control the radio waves,broadcast television channels, newspapers, or other forms of communications, they now add to thesesources of information control cyberspace and its component aspects, websites, and social media. 2 Thisallows Russia to influence audiences around the world. Propaganda, disinformation, and the manipulationof the informational aspects of both conflict and nonconflict settings has been a persistent attribute ofstate behavior. 3 The new dimension added to the conduct of hostilities created by cyberspace is both achallenge to conventional hybrid information manipulation tactics and a benefit. Even though the tacticalgains achieved through cyberspace in Georgia by Russian non-state actors had limited impact, thestrategic and psychological effects were robust. The plausibly deniable nature of the cyber side of conflictshould not be understated and adds a new dimension to hybrid warfare that once required state resources1Taubman, “Soviet Lists Afghan War Toll”; History.com staff, “November 4, 1956.”Schlosser, Cold War on the Airwaves; Sweeney, Secrets of Victory; Price, "Governmental Censorship in WarTime."23Lasswell, "Theory of Political Propaganda"; Treverton, Covert Action.3

Analyzing the Russian Way of War: Evidence from the 2008 Conflict with Georgiato accomplish. Now, managed through forums and social media, decentralized noncombatants can jointhe fight. Arguably, the inclusion of cyber means into a kinetic battle, not as a standalone effect but ratheras a force multiplier, constitutes a logical progression to the natural evolution of conflict anddemonstrates the value of information operations (IO) during conflict.The war was a wake-up call for Russia. Even though Moscow won the war and despite its relativelysophisticated cyberattack, it arguably lost the battle for controlling the narrative. Russian forces could notengage in information-driven or network-centric warfare, lacked precision-guided munitions, and were illsupplied due to insufficient spending and attention paid to its armed forces over the preceding twodecades. The war also served as a wake-up call for reformers within its defense community, as the Russianmilitary lacked the operational experience and training, and these numerous shortfalls revealedthemselves in combat. Put simply, the state of much of its Soviet-era military equipment, not to mentionits command and control (C2) capabilities, proved an embarrassment. The war would spur Russia toreform and modernize its military by moving from an old division structure toward a more decentralizedone reliant on brigades given greater autonomy. Russia would also shift away from the use of conscriptsand rely increasingly on so-called kontraktniki, volunteer soldiers who signed up for two-to-three-yeartours and were more professional than conscripts.Russia also sought to boost its IO and electronic warfare (EW) sophistication. Nearly a decadeafter the 2008 Russia-Georgia War, Moscow still prefers to operate in gray zones, where economies areinformal, local rule is subdivided, and information and facts are ambiguous. Truth appears to be one ofthe least precious commodities in its tool kit.The Caucasus region remains important to Russian war efforts elsewhere, as Russia looks todevelop an A2D2 zone around the Caspian Sea. Russian strategic bombers and sea-based missiles launchfrom the Northern Caucasus to Syria, Russia’s first expeditionary mission since Afghanistan. According tothe United States’ Defense Intelligence Agency, “Russia’s forces are becoming more mobile, morebalanced and capable of conducting the full range of modern warfare.” 4The purpose of this report is to examine Russian military strategy and how it was shaped by the2008 Russia-Georgia War in order to understand Moscow’s military objectives in the current conflict inUkraine and how it executes cyber, psychological, and so-called “hybrid” warfare against Western states.A number of our sources said that had the West studied the lessons of that conflict, we in the West mayhave been better prepared to prevent Russia’s 2014 annexation of Crimea and avoid hostilities in Ukraine.4E. Schmitt, “Vast Exercise Demonstrated Russia’s Growing Military Prowess.”4

Analyzing the Russian Way of War: Evidence from the 2008 Conflict with GeorgiaThe report will also analyze the types of warfare Russia executes—exploring how its hybrid, cyber, andinformation aspects are integrated into Russia’s increasingly advanced conventional capabilities—and layout a series of recommendations for how the US military and its counterparts in Europe should respond.The report’s central findings are the following: The 2008 Russia-Georgia War was a playbook of its later operations in Ukraine, in terms of how itprobes for weak spots, exploits internal crises, and seeks to redraw borders along its buffer regionwith NATO, an area it calls its “zone of privileged interest.” After 2008 the West should have takenproper remedies to deter Russia from similar incursions to annex territory, a violation ofinternational norms on the legitimate use of force. The 2008 Russia-Georgia War served as a wake-up call for Russia to reform and modernize itsmilitary, reversing its dependency on unprofessional conscripts, Soviet-era equipment, and poorlytrained field officers. The war also served as a dress rehearsal of sorts for what was to come inUkraine. Nearly a decade later, the Russian military is more professionalized, responsive, andcapable to mobilize on short notice than it was previously, especially its elite special forces. 5 The 2008 Russia-Georgia War was about militarily balancing against NATO just as much as it wasa regional political dispute between Moscow and Tbilisi. Russian grand strategy for theforeseeable future will be to control an uncontested sphere of influence in the post-Soviet region,assert Russia’s voice and influence globally, and constrain the United States. Specifically, Russiaseeks to create a zone of “privileged control” around the Black Sea. By annexing Crimea in 2014,where its long-standing Black Sea Fleet is based, and deploying forces in the southern Caucasus,Russia aims to keep this area not merely as a strategic buffer but also as an alternate transportcorridor for its military and energy needs. Control over this corridor also gives Russia greaterleverage over Iran and Turkey and boosts its influence in the wider Middle East. Russia has alsointensified its exercises, training, and professionalism of its military forces in the region. To achieve its military strategy on the cheap, Russia has relied and will continue to rely on a hybrid,or nonlinear, approach to modern warfare—which seeks to merge political warfare withconventional means. Along these lines, it will continue to weaponize information, orchestrate viathird parties cyberattacks against government and civilian targets, carry out electronic warfare,5On this point, see Golts and Kofman, Russia’s Military, 9–10.5

Analyzing the Russian Way of War: Evidence from the 2008 Conflict with Georgiaand utilize local proxy volunteers as well as Russian soldiers who do not wear insignia. When itcomes to cyberwarfare, Russia’s reliance on third party actors to execute the state’s cyber dirtywork, given its many advantages, from plausible deniability to ambiguous attribution, is unlikelyto go away as a tactic anytime soon. In sum, Russia will continue to “fail upward,” barring outside resistance: As it arguably declines asa major power, it will punch above its weight, largely by exploiting weaknesses in the West (cybervulnerabilities, disagreements within NATO on defense policies, etc.), sowing uncertainty incountries bordering it, intervening in elections and conflicts where it sees a vacuum in Westernleadership (Ukraine, Syria), and contorting international rules and norms toward its will. It hasshown a willingness to incur risks that Western powers, including the United States, is not. Thismakes its willingness to escalate, provoke, and push boundaries—figuratively and literally—thatmuch greater. Complicating matters, Moscow will continue to operate in a gray zone and sow alevel of chaos within states it considers part of its zone of privileged interest to prevent them fromjoining these Western clubs, undermine their democratic governance, and remind them of theirdependence on Russia for resources, security, and economic livelihood.6

Analyzing the Russian Way of War: Evidence from the 2008 Conflict with GeorgiaMap of Georgia 6“Administrative Map of Georgia,” Nations Online, accessed October 21, rgia map2.htm.67

Analyzing the Russian Way of War: Evidence from the 2008 Conflict with GeorgiaIntroductionThe Jvari Monastery, built in the sixth century,and South Ossetia, the war was about largersits high above a central artery that slicesissues related to the expansionism of NATO, thethrough a picturesque gorge linking Gori toisolation of Russia, and the prevention of its nearTbilisi. On the fourth day of the 2008 August war,abroad from reorienting themselves westward.Russian forces advanced as far as nearbyThe war was believed to be planned well inMtskheta, within artillery range of this temple,advance, given the careful execution of Russia’sjust outside Tbilisi. The topography of this areaunits and formations, as well as the degree ofwould make any advancing army twitchy, givencoordination between its cyber, military, andits wealth of natural defensive fortifications, asdiplomatic offensives. The timing and location ofwell as its canopy of forest for cover andthe war caught many off guard on both sides.concealment. According to Georgian militaryThe expectation was that if war were to erupt, itofficials, the Georgian army was prepared to fallwould occur in Abkhazia, not South Ossetia.Still, there were plenty of warning signsback and fight a prolonged insurgency if thefartherthat war was on the horizon, if not imminent.southeastward. 7 There were reports of RussianThe leaderships of Russia and Georgia hadaircraft shelling the television tower that soarsengaged in a series of verbal volleys that hintedhigh above Tbilisi, as European officialsat brinkmanship-like provocations. Neither side,scrambled to get both sides to declare a cease-one might argue, wanted war, yet neither werefire. Much of the world were glued to theirthey prepared to back down in the face of atelevisions, but they were watching the Beijingdirect challenge. In previous summers, there hadOlympics, not the unfolding war in Georgia. Evenbeen a series of cross-border skirmishes thata number of Georgians were caught off guard,never escalated. Many observers reckon thatgiven that August is when politicians andwhat changed in 2008 was an externaldefense officials typically head for the Black Seaenvironment that altered Russia’s calculationcoast for vacation. Even Georgia’s best-trainedand willingness to incur risk: First, the previousbrigade was in Iraq.year, Kremlin proxies had carried out aRussianforceshadadvancedEven though the immediate goal of thecyberattack against Estonia, the first of its kind,Russians was to establish control over Abkhaziawhich this report will explore further. This action7From interviews with senior Georgian military officers in Tbilisi, June 12, 2017.9

Analyzing the Russian Way of War: Evidence from the 2008 Conflict with Georgiaemboldened Russia to combine offensive cyberdeclaring independence at the barrel of a guncapabilities with its conventional operations in(given NATO’s 1999 war in Kosovo). Theany future conflict. Second, the war clarified theencroachment of NATO and declaration ofKremlin’s thinking that future wars would beKosovar independence left Moscow feeling bothlimited ones fought along Russia’s periphery.isolated and neutered diplomatically. 8Russia remains a declining power with aFinally, presidential elections in the Unitedpoliticalpopulation diminishing in size. 9 Its economy isconfiguration of two former adversaries. Russiafar from modernized, and its state budget iswas nominally under the control of its newhighly dependent on one industry for income: oilpresident, Dmitry Medvedev, who was seen asand gas. Its previous actions against Georgiamore of a moderate than his predecessor,were driven in part by neurosis and nostalgia.Vladimir Putin.After all, Georgia lies at an important nexus—aStatesandRussiachangedtheIn the United States, the administrationstrategic crossroads between the former Sovietof George W. Bush, who had a highway namedUnion and the Middle East; wedged between theafter him on the edge of Tbilisi, was coming to aoil-rich Caspian Sea and Black Sea; and a naturalclose. Georgia’s cocksure president, Mikheilbuffer for Russia to its north, an area wracked bySaakashvili, saw in Bush an important ally whoMuslim separatism and extremism. For much ofwould have his back were he to go to war withtheRussia, a window that might close after Bush leftcounterinsurgency only miles to Georgia’s north.the White House the following winter. Finally,Sochi, site of the 2014 Winter Olympics, also sitstwo important events occurred in Europe earlyjust north of Abkhazia, one of Georgia’sthat year. In Bucharest, Georgia and Ukraineseparatist regions. Russia has sought improvedwere denied a membership action plan, or MAP,relations with Turkey, which lies farther to theto join NATO, but the door was left ajar enoughsouth, as a way to strengthen its influence in theto leave Russia feeling unsettled. Second, KosovoMiddle East. Georgia has also long been thewas given independence, against the wishes ofplayland of tsars and Soviet leaders, given itsRussia and Serbia, which set a dark precedent forscenic beaches, mountain vistas, and fine food.81990s,RussiawagedaAsmus, Little War That Shook the World.Drawing on the realist international-relations literature, we assess power using both latent (wealth andpopulation) and military (expenditures and force size) measures; see Mearsheimer, Tragedy of Great PowerPolitics, 60. Drawing on the literature (see Levy, “Declining Power and the Preventive Motivation for War”;Organski and Kugler, War Ledger), we also focus on relative power when determining declining powers.910brutal

Analyzing the Russian Way of War: Evidence from the 2008 Conflict with GeorgiaMany moneyed Russians own assets there.about its future trajectory. Saakashvili sawRussia’s nostalgia, as many experts havehimself as a state builder; part of his mission wasdescribed, can be likened to Britain’s colonial-erato restore Georgia’s borders. A number ofview of India: its “jewel in the crown.” Georgia isanalysts described Georgia at this time as aalso the birthplace of Joseph Stalin.“failed state.” 12This report proceeds over six shortAlthough a small country (population:achapters. The first examines the post–Cold Warhodgepodge of various ethnicities. Along itshistory of Russia and Georgia to set up the war’sperimeter, mountainous terrain provides itsstructural, mezzo, and immediate causes. Thevarious clans and ethnic groupings naturalnext chapter examines Russia’s grand strategydefensive fortifications to survive the writ of theand how the 2008 war both shaped and wasstate or advancing armies. Warlordism took holdshaped by its use of what some call “hybridalong Georgia’s lawless periphery after thewarfare.” The third chapter details the war at theSoviet Union collapsed. 10 Georgia would adopt atactical and operational levels, to glean lessonskind of “Finlandization” policy toward Russia. 11of how Russia will fight in future wars, examinePartly this was for fear of rocking the boat andthe decisions made, and understand how bothstirring up ethnic resentments in its peripheralsides learned from their mistakes and reformedareas; partly it was out of diplomatic inertia. Totheir militaries. The next chapter looks atkeep Georgia weak and divided, Russia sought toRussia’s cyber capabilities and examine its cyberkeep the lid on the separatist wars alongstrategy in the context of its psychological and IOGeorgia’s periphery, to freeze them as a waycampaign. The following chapter explores howfrom keeping Georgia unstable and dependentthe Russia-Georgia War shaped the Kremlin'son Russia. No European organizations wouldcampaign in Ukraine from 2014 to the present.come knocking on Georgia’s door so long as one-The reportfifth of its territory was in dispute and the subjectrecommendationsof periodic violence. Georgia emerged from theactions in Ukraine and elsewhere going orwithacounteringseriesofRussian1990s, a lost decade, broken, poor, and unclear10Marten, Warlords.This refers to when a smaller country stays on favorable terms with its stronger and larger neighbor. The phraserefers to post–World War II Finland, which held a neutral policy toward the Soviet Union for much of the Cold War.11Goltz, “Paradox of Living in Paradise,” in The Guns of August 2008, ed. Svante E. Cornell and S. Frederick Starr,27.1211

Analyzing the Russian Way of War: Evidence from the 2008 Conflict with GeorgiaChapter I – History of Bad BloodA number of analysts describe the 1990s as a lostminorities pushing for greater self-autonomy.decadeRussianStoking these ethno-nationalist sentiments wasFederation. 13 Georgia saw its economy stagnate,Georgia’s first president, Zviad Gamsakhurdia,its hinterland provinces try to secede, and itswho proudly declared “Georgia for Georgians.” 14border left contested. Contributing to theRussia intervened militarily, nominally on thetension was a violent counterinsurgency againstside of the separatists; and after the wars wereIslamists across its northern border, some ofleft unresolved, it left a battalion of RussianwhomGeorgia’s“peacekeepers” deployed in Abkhazia (roughlyungoverned Pankisi Gorge. Russia saw its empire2,300 soldiers) and South Ossetia (500). 15 For thecollapse; its economy sink; and its previousrest of the decade, Georgia’s hinterlands becamemortal enemy, NATO, inch closer to its borders.a bastion of criminality, warlordism, smuggling,During this decade, Russia fought a long-and corruption. 16forGeorgiaenjoyedandsanctuarytheinstanding war against separatists in Chechnya,That went in spades in South Ossetia.while stirring ethnic uprisings in nearby placesOssetians are not ethnically Georgian—they arelike South Ossetia and Abkhazia, two breakawaycloser to Persian—yet having arrived to thisregions of Georgia.region only a millennium ago, they areAfter the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991,considered relative newcomers. From the timeGeorgia declared its Soviet constitution null andof the tsars to the Bolsheviks, they have enjoyedvoid, which in turn triggered a series of uprisingscloser ties to Moscow than to Tbilisi. 17 In 1990,along its periphery for greater self-autonomy.South Ossetia launched a campaign to reuniteWhen Georgia gained its independence, it waswith North Ossetia after Tbilisi stripped Southmandated to keep the same borders it had as aOssetia of its independence. That set offrepublic, so there was no chance to redraw thesporadic fighting between Georgians andborders. Akin to Texas in the 1840s, areas alongOssetians, displacing some sixty thousandthe Georgian frontier were rife with ethnicpeople and leading to a cease-fire in 199213This comes from discussions with Georgia analysts in Tbilisi, June 11–15, 2017.14Asmus, Little War That Shook the World, 60.15Lavrov, “Timeline of Russian-Georgian Hostilities in August 2008,” 39.16Marten, Warlords.17Goltz, “Paradox of Living in Paradise,” 18.13

Analyzing the Russian Way of War: Evidence from the 2008 Conflict with Georgiasponsored by the Organization for Security andnation building, while Russia under Boris YeltsinCo-operation in Europe (OSCE). 18 The province,sought to retain a zone of influence in theparticularly its capital Tskhinvali, devolved into asouthern Caucasus. At times, these two goalsAbkhazia,clashed. Shevardnadze was seen by somemeanwhile, was more or less ethnically cleansedGeorgians as a toady of the Kremlin, given his oldby powerful Georgians under Soviet rule—Soviet ties as a high-level apparatchik (he wasnamely, Joseph Stalin and Lavrenti Beria (aformerly minister of foreign affairs). And Russianative of Abkhazia who was a former marshal ofstationed forces in four bases throughoutthe Soviet Union). Buttressing the Black SeaGeorgia proper to act as nominally neutralcoast and dotted with spas and soaring peaks,peacekeepers, which Georgians suspected as athe region became popular vacation grounds forway of Moscow maintaining its imperial-likeSoviet apparatchiks.hegemony in the region. Under Shevardnadze,popularhavenofsmuggling. 19Violence soon erupted in Abkhazia, asGeorgia adopted a friendly policy toward Russia.local police began cleansing the area of ethnicPartly this was for fear of rocking the boat andGeorgians and foisted the Abkhazian flag highstirring up ethnic resentments in its peripheralabove parliament. Fighting erupted shortly after,areas; partly it was out of diplomatic inertia.but it became clear that Georgians were not justIndeed, Georgia has long stirred up anfighting ethnic Abkhazians but rather a motleyemotional attachment for Russia. The countryarmy of Circassian fighters, mercenaries fromenjoyed a privileged status under Stalin,abroad, and elements of the Russian military. AnGeorgia’s native son. Its Black Sea coast was aearly hint, the Abkhazians lacked an air force, yetfavored vacation spot for tsars and Bolshevikthe Georgian military found itself up againstleaders alike.

limited war with limited objectiv es, yet it was arguably a watershed in the annals of modern war. It marked the first invasion by Russian ground forces into a sovereign nation since the Cold War. It also marked a breakthrough in the integration of cyberwarfare and other nonkinetic tools i nto a conventional strategy —