Transcription

Volume 8/ Number 1 (1-14)February 2021https://jurnal.ugm.ac.id/rubikonPOSTCOLONIAL TRANSLATION STUDIES: FOREIGNIZATION ANDDOMESTICATION OF CULTURE-SPECIFIC ITEMS IN OF MICE AND MEN’SINDONESIAN TRANSLATED VERSIONSHafizha Fitriyantisyame-mail: hfitriyantisyam@gmail.comAris MunandarUniversitas Gadjah Madae-mail: arismunandar@ugm.ac.idABSTRACTResistance to Western Culture can be seen through translator‟s strategyof translating novels. This research aims to analyze the translation ofculture-specific items in Indonesian translated versions of Of Mice andMen, originally written by John Steinbeck. The selected translatedversions belong to the work of Pramoedya Ananta Toer (2003) andAriyantri E. Tarman (2017). The translations of culture-specific itemsare analyzed under Transnational American Studies paradigm to findout the dominant translation principle applied in both translatedversions and the results are discussed from the perspective ofpostcolonial translation studies. From the data, it is found out that thedomestication principle is more dominant than foreignization strategy.Analyzed from postcolonial translation studies, the tendency to use thedomestication principle in translated novels show the efforts of thetarget culture to fight against Western culture as the source culture.Although both Indonesian versions of Of Mice and Men mostly applythe domestication principle, the recent translated version (T2) shows anincrease in the use of foreignization principle in which Englishloanwords are frequently used. From a postcolonial translation studies‟perspective, it can be concluded that target culture is against Westernculture; however, the signs of cultural imperialism, especially linguisticimperialism, have grown in the recent years.Article informationReceived: 29 January 2021Revised: 12 February 2021Accepted: 26 February 2021Keywords: culture-specific items; domestication; foreignization;postcolonialism; translation strategiesDOI: le 478This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License

RUBIKON Volume 8/ Number 1February 2021INTRODUCTIONTranslation is understood as the act oftransferring meanings and culture from thesource text to the target text (Bassnett &Lefevere, 1998). It means that a translatorcarries a responsibility to transfer a source textinto a target text as precisely as possible.Translating a text is inseparable fromtranslating a culture because culture iscontained within a language and when alanguage is translated, the culture might bepresented in the translated version dependingon the translator‟s choice. The evidence thatculture is also translated alongside the text canbe seen from the way a translator translates thesource text‟s culture-specific items. Baker(1992) defines culture-specific items as objectsthat are culturally tied to a certain culture,which can appear as abstract or concreteconcepts, religious beliefs, social customs, andtypes of food. Culture-specific items have awide range of categorizations, includingecology, material culture, social culture,organizations, customs, activities, procedures,concepts, gestures and habits, and slang(Newmark, 1988; Espindola & Vasconcellos,2006; Chung-ling, 2010).Translating culture-specific items can be achallenging task for the translator. One reasonis caused by the unavailable of equivalents inthe target culture. Another reason is caused bythe status of language that is held by thesource and the target language. The statusescan be divided into a dominant language and adominated language. A language is dominantif it is learned; spoken; and usedinternationally. English is one of the dominantlanguages. Otherwise, a language that is lessknown internationally is considered as adominated language. Translation plays animportant role in bridging the dominant and2dominated language. For instance, the shortageof literary works in South Africa in the 1950sled the African translators to translate Englishliterary works to improve their literature(Mlonyeni & Naudé, 2004). One can see thepositive side of translation from the previouscase. However, postcolonial scholars havecautioned regarding the negative side oftranslation that may harm the dominatedculture. According to Bassnett (1996),postcolonial theorists acknowledge theexploration of power within the translation.There is power inequality between the sourcetext and the target text because of the status ofthe language.Researches that combine translationstudies and postcolonialism are not new.Several previous studies had observed thistopic and object. For instance, Čerče (2017)conducted research that analyzes thetranslation process of working-class languagein Of Mice and Men. The working-classlanguage refers to the vernacular English thatwas spoken by poorly educated characters inthe novel. The results show that the vernacularEnglish was changed into formal vocabulariesin the Slovene language. Čerče (2017)suggested translators should stick to linguisticand cultural nuances of the original text topreserve the characters‟ traits and allow thetarget readers to get a sense of the vernacularlanguage of the original text. Another researchwas conducted by Hu and Shi (2015) whoexplored the translation of Chinese literarywork into English by Buck and Saphiro andhow their translations were seen from apostcolonialperspective.Fromthepostcolonial point of view, Buck‟s translationis an example of resistance over culturalimperialism since he faithfully followed the

Hafizha Fitriyantisyam & Aris Munandar – Postcolonial TranslationStudies: Foreignization and Domestication of Culture-Specific Itemsin Of Mice and Men’s Indonesian Translated Versionoriginal text. On the other hand, Saphiro‟stranslation tended to blend the Chinese andEnglish languages without ditching themeanings of original texts. It can be concludedthat Saphiro did not only „copy‟ the originaltext, but he also recreated new texts throughtranslation (Hu & Shi, 2015). Thus, the recentresearch attempts to fill in the gaps in whichthe translation of culture-specific items inIndonesian versions of Of Mice and Men froma postcolonial perspective has yet to beexplored.This research aims to analyze the powerinequality in translation, as seen from apostcolonial translation studies. The materialobjects are American novel Of Mice and Menby John Steinbeck and its Indonesiantranslations. This novel has been translatedinto several Indonesian versions and thisresearch uses the first version by Toer (T1)and the most recent version by Tarman (T2).The first version was published in 2003 byLentera Dipantara publisher; meanwhile, therecent version was published in 2017 byGramedia Pustaka Utama. The considerationof choosing these two versions is based ontheir publication years. Both versions werepublished fourteen years apart. Since languageis dynamic and develops over time (Harya,2016), the patterns of language developmentcan be observed and it helps discover thetrends of the language used in a literary work.This research is under the TransnationalAmerican Studies paradigm that observes theeffects of American culture on a nation beyondthe western hemisphere. According to Kimand Robinson (2017), the application of theTransnational American Studies paradigm iscommonly applied to studies with themesrelated to colonial, imperial, and postcolonial;which are relevant from the slavery era to themodern era. In this research, the focus is set onthe postcolonial perspective that explores thepower relation between the United States andIndonesia through translation works.This research uses the theory oftranslation principles by Venuti. Venuti (2001)divides translation principles into two types:foreignization and domestication. Accordingto Venuti (1995), applying foreignizationsends the reader abroad, and this principlevalues the linguistic and cultural differencesthat appear in the foreign texts. In short, thisprinciple allows the target readers to beacquainted with the source culture. On theother hand, there is the domestication principlethat is the otherwise of foreignizationprinciple. According to Yang (2010),domestication adopts fluent style translationthat minimizes the strangeness of foreignterms that makes domestication is morereader-oriented than foreignization. The focusof the domestication principle is to make thetranslation reader-friendly and natural.However, the downside of the domesticationprinciple is the translated version might appearunnatural if the translator does not select theequivalent wisely. Besides foreignization anddomestication, there is an additional principlenamed mixed strategies (Judickaitė, 2009).This principle serves two or more translationstrategies in translating one term. The mixturecan take place between the foreignizationforeignization continuum and the oppositeforeignization-domestication continuum.The translation strategies in this researchfollow the classification of translationstrategies by Judickaitė (2009) described asfollows:3

RUBIKON Volume 8/ Number 1February 2021Foreignization Principle Preservation strategy: the original terms arepreserved without any changes because ofunavailable of equivalents. Addition: the translator puts additionalinformation related to the translated itemswithin the text or in the footnotes. Naturalization: the items or termsexperience changes morphologically orphonologicallythatfollowthepronunciation in the target culture. Literal translation: the items or terms aretranslated in literal ways, which is highlylikely to be translated word-by-word.Domestication Principleseen as a double-edged sword that canpromote the dominated culture or promoteimperialism. Tymoczko (2014) mentions thisissue in her book, “ Conversely, when thetranslation is done by the colonized subjectsthemselves, the possibility of gathering andcreating information can be turned to powerfulends, including counterespionage, conspiracy,and mutiny, leading to self-definition and selfdetermination ” (Tymoczko, 2014, p. 294).In other words, the status of language thatbecomes the source text and which translationprinciple frequently applied by the translatorsshould be taken into consideration beforeconcluding whether the translation is used topromote imperialism or to challenge it.that alters the source language‟s terms tosuit the culture of the target readers.Omission: this translation strategy omits asource culture‟s term in the translatedversion.Globalization: the translated version uses amore general term to translate the sourcetext‟s culture-specific item.Translation by a more concrete word: it isalso called localization in which the sourceculture‟s item is translated into somethingspecific in the target culture‟s language.Creation: it is similar to free translation inwhich the translator has the freedom totranslate a term that might not directlyrelate to the original text.Equivalent: this translation strategy isapplied when both source text and targettext have similar equivalents.Linguistic imperialism is one of theelements of cultural imperialism that mayresult in the dominating force of English toother languages (Khodadady & Shayesteh,2016). Linguistic imperialism itself can be adanger that has the potentials to threaten thedominated cultures‟ social, religious, andcultural values (El-qassaby, 2015). Byapplying the domestication principle, thedanger of linguistic imperialism can beminimized. It is the translator‟s decisions andefforts to make Western culture appear lessnoticeable in his/her translation. These viewsare in line with Tymoczko‟s views towardstranslation as a medium to express thedominated culture‟s self-determination andself-definition (2014) and Wang‟s argument(2009) in which the legacy of colonialism canbe challenged and decolonized throughtranslation.In general, the foci of postcolonial criticsare to promote and celebrate diversity whileshielding themselves from the influence ofWestern culture (Barry, 2002). From apostcolonial perspective, translation can beIn summary, the postcolonial translationstudies focuses on power inequality that iscontained in the source text and the target text.Translation can be regarded as a means ofcolonization or a means to resist colonization Cultural equivalent: a translation strategy 4

Hafizha Fitriyantisyam & Aris Munandar – Postcolonial TranslationStudies: Foreignization and Domestication of Culture-Specific Itemsin Of Mice and Men’s Indonesian Translated Version(Tymoczko, 2014). The view can differ basedon which culture is the source text.Jacquemond (1992, as cited in Naudé, 2005)hypothesizes that a translation activity fromthe dominant culture to a dominated culture ismore likely to apply the domesticationprinciple over the foreignization principle.Related to this hypothesis, postcolonialtheorists also consider translation as a tool todecolonize colonialism and strengthen theposition of the dominated culture (Wang,2009).This research employs the descriptivequalitative method. Qualitative research allowsthe researcher to explore, identify, andinterpret the recurring patterns that are foundin the collection of data (Nassaji, 2015).Hence, the qualitative method is suitable forthe research that concentrates on the patternsof culture-specific items translation in theresearch‟s objects. However, this research stillapplies to numbers in the process of collectingdata as supplementary supports for the dataanalysis. The data of this research are takenfrom primary sources and secondary sources.The primary sources of this research aretaken from an American novel, Of Mice andMen– originallywrittenbyJohnSteinbeck, which are translated into theIndonesian language by two IndonesianNo123456Categoriestranslators: Pramoedya Ananta Toer (T1) andAriyanti E. Tarman (T2). The T1‟s versionwas published in 2003 by Lentera Dipantarapublisher and the T2‟s version was publishedin 2017 by Gramedia Pustaka Utama.The secondary sources consist ofdictionaries, scientific journal articles, onlinenews, and web articles that can support theprocess of classifying the translation strategies.Both English and Indonesian dictionaries areused in this research. For the Englishdictionary, the Merriam-Webster onlinedictionary is used to look up the Englishdefinitions of culture-specific items. For theIndonesian dictionaries, Kamus Besar BahasaIndonesia (online) and Kamus Kata-KataSerapanAsingdalamBahasaIndonesia. Kamus Besar Bahasa Indonesia isused to find out the variety of meanings thatare available in Indonesian terms. On the otherhand, Kamus Kata-Kata Serapan Asing dalamBahasa Indonesia is used to identify the originof loan words in the Indonesian language thatare not shown in Kamus Besar BahasaIndonesia.DISCUSSIONBased on the data, the total of culturespecific items found in the source text is 153items. The detailed result can be seen in thefollowing table.Numbers ofData196027EcologyMaterial CultureSocial CultureOrganizations, Customs, Activities,4Procedures, and ConceptsGestures and Habits6Slangs and Idioms37Total153Table 1. The classification of culture-specific itemsPercentage12.4%39.2%17.7%2.6%3.9%24.2%100%5

RUBIKON Volume 8/ Number 1February 2021The data use the classification of culturespecific items by Newmark (1988) and itsdevelopments by Espindola and Vasconcellos(2006), and Chung-ling (2010). The culturespecific items are dominated by materialcultured, followed by slang and idioms, socialculture, ecology, gestures and habits, andNoorganizations, customs, activities, procedures,and concepts. These culture-specific items areanalyzed by Judickaitė (2009) translationstrategies. The comparisons of translationstrategies applied by T1 and T2 can be seen asfollows:Numbers ofDataT1T2Translation 34PreservationAdditionNaturalizationLiteral 5Cultural Equivalent12Omission9Globalization27Translation by a More Concrete Word9Creation13Equivalent31Total101Mixed StrategiesPreservation – Equivalent4Addition - Equivalent1Addition – Cultural Equivalent2Naturalization - Equivalent1Total8Table 2. Overall translation strategiesBased on the data, the dominanttranslation principle applied by bothtranslators is the domestication principle. Itmeans the translators change the source text‟sculture-specific items into objects that aremore familiar to the target readers. Accordingto Yang (2010), the presence of foreignness isminimized in the domestication principle tomake the translation reader-friendly. It isreflected in the word choices in thedomestication principle. For instance, T1translates the sheriff into kepala polisi. Thisoccupation, which is in the social culturecategory, is translated by the cultural6equivalent strategy. A sheriff is one of the lawenforcement agencies in the United States thatis in charge of securing territory fromcriminalities. According to the InternationalAssociation of Chiefs of Police (2018), the lawenforcement agencies in the United Statesconsist of local police, state police, specialjurisdiction police, and deputy sheriff. In thetarget language, law enforcement is performedunder a single main agency, which is theIndonesia National Police. Since theoccupation as a sheriff does not exist in thetarget language, it is replaced by polisi that has

Hafizha Fitriyantisyam & Aris Munandar – Postcolonial TranslationStudies: Foreignization and Domestication of Culture-Specific Itemsin Of Mice and Men’s Indonesian Translated Versionsimilar responsibilities and job desks to asheriff.The foreignization principle is in thesecond place after the domestication principle.This principle attempts to introduce the foreignculture into its target readers. Even thoughboth translators almost score the same numberin foreignization, the translators favor differenttranslation strategies. T1 prefers using literaltranslation; on the other hand, T2 prefers usingnaturalization strategy. The example of T1using literal translation can be seen from theway he translates food, for instance, hot cakeis translated into kue hangat. Hot cake refersto the United States‟ cuisine that resemblesmodern pancakes. According to Goldstein(2015), the term hot cake was first mentionedby Pennsylvania governor‟s letter, whichreferred to a cuisine of Native Americans. Thegeneralized concept of a hot cake as a pancakebegun in the mid-nineteenth century in whichcommercial baking powder became availablein the market and thick-layered pancakesstarted becomingAmerican‟sfavorite(Goldstein, 2015). Therefore, a hot cake has itshistory in American culture. Indonesianreaders in the 1950s might not be familiar withthis food. To overcome the translationdifficulty, the literal translation is applied inthis part. Kue hangat, in this context, can beperceived as traditional snacks in theIndonesian language. On the other hand, T2favors the naturalization strategy, which meansit is more likely to find loanwords in hertranslation work. Some loanwords that shechooses have equivalents in the Indonesianlanguage; however, the equivalent is not aspopular as the loanword. For instance, T2translates cream into krim. The Indonesianlanguage has the equivalent of cream, which iskepala susu as in how T1 translates cream.However, the term kepala susu might appearunfamiliar to the young readers since the termkrim is more frequently used in dailyconversation in the present day.The principle that gets the least total ismixed strategies. According to Judickaitė(2009), mixed strategies are a combination oftwo or more translation strategies. Forinstance, the terms that are translated bypreservation – equivalent strategy usuallypreserve the proper noun and translate thenoun, for instance, Stetson (proper noun) andhat (noun) are translated into topi (noun)Stetson (proper noun). Another example isaddition – equivalent that inserts additionalinformation besides using its equivalent. It canbe found in the translation of a horseshoegame in which the first translator insertsexternal addition in the footnote meanwhilethe second translator includes the verb lempar(throw) within the text that describes the waythe game is played.Postcolonial Translation Studies: LookingBeyond Translation PrinciplesThe results show that 66% of culturespecific items in the original novel aredomesticated, followed by the application offoreignization principle 28.8% (T1) and 28.1%(T2), and mixed strategies 5.2% (T1) and 5.9%(T2). Such wide gaps in the application oftranslation principles are examined from thepostcolonial perspective that concerns thepower relation between dominant anddominated culture. The findings showcorrelations to Tymoczko‟s views (2014) inwhich translation is done by the dominatedculture can appear as a powerful mutinytoward Western domination and it leads to thetarget culture‟s self-definition and selfdetermination. The dominant use ofdomestication principle in this research reveals7

RUBIKON Volume 8/ Number 1February 2021that the translators attempt to preserve theirtarget culture‟s norms, which is in line withTymoczko‟s argument (2010) in whichdomestication can induce equality in culturalexchange between a dominant and dominatedculture. Nevertheless, the results gained fromboth versions show that linguistic imperialismmakes some progress in penetrating the targetlanguage in the recent version, which isindicated by the second translator‟s choice touse preservation and naturalization strategy forterms that have equivalents in the targetlanguage.Bringing a Sense of Familiarity to theTarget ReadersOne of the translators‟ attempts to bring asense of familiarity is by localizing the sourcetext‟s culture-specific items. It can be seen inthe cultural equivalent strategy in which thesource text‟s culture-specific items arereplaced by terms that are well known by thetarget readers. For instance, the alterations ofecology category mostly apply the culturalequivalent strategy. It is known that someplants and animals are culturally bound to acertain culture, which means the same speciescan be rarely found in another culture. Bothtranslators solve this translation difficulty byreferring to the closest family of plants andanimals that can be found in the target text.For instance, a coyote is translated intoserigala (wolf) by the first translator; deer istranslated into kijang (antelope) by the secondtranslator. Considering coyote is native toNorth America, the same species might not beknown by the target readers. The animalsimilar to a coyote in terms of itscharacteristics is represented by a wolf in thetarget language since the wolf is morerecognizable among the target readers.8The same case appears in the translationof deer into kijang in which kijang is one ofthe native species of deer in Indonesia. Thedecision to find animals that share similaritiesto the source text‟s culture-specific items canease the target readers‟ reading experience.Another example is the alteration of measuringsystems. The second translator changes all theUnited States‟ measurement systems intoIndonesian‟s measurement systems. Mile,pound, and acre are transformed intokilometer, kilogram, and hektar. The secondtranslator not only translates the units, but shealso converts the units. For instance, a quartermile is translated into 500 meter. It is a carefulconsideration to change the foreignmeasurement units to the target readers‟customary.Resisting the West’sChallenging ImperialismIdeologyandBased on the findings, the domesticationprinciple resists orientalism, which iscommonly found in the first translator‟s work.The resistance towards orientalism is reflectedthrough the way the first translator changes thereligious terms in his translation. The religionrelated item is presented as follows:ST: “Jesus Christ, you‟re a crazy bastard!”(Steinbeck, 1994, p. 12)TT: "Ya, Rasul. Betul-betul haram jadahkau ini!?" (Steinbeck, 1994/2003, p. 10)The first translator domesticates thesource text by applying an equivalent strategyin which the term Jesus Christ is translatedinto Rasul (prophet). The example of JesusChrist in this context does not refer to theactual Jesus; the example above is counted asan interjection that expresses disappointment.However, the expression itself is closelyrelated to Christianity. The first translatordecides to change it into Rasul, which is closer

Hafizha Fitriyantisyam & Aris Munandar – Postcolonial TranslationStudies: Foreignization and Domestication of Culture-Specific Itemsin Of Mice and Men’s Indonesian Translated Versionto the Islamic term in the target culture‟scustomary. The second translator alsodomesticates the religion-related term, eventhough she applies a different translationstrategy. The example can be seen as follows:ST: “Jesus Christ, you‟re a crazy bastard!”(Steinbeck, 1994, p. 12)TT: "Ya Tuhan, kau keparat sinting!"(Steinbeck, 1994/2017, p. 11)The second translator‟s word choice ismore general since she applies theglobalization strategy. Jesus is acknowledgedas the Son of God by Christians and the targetculture only has one closest expression, in thegeneral sense, which has a similar effect toJesus Christ that is Ya Tuhan. The wordchoices that are picked by both translatorsmight be influenced by the fact that Islam isthe largest religion in Indonesia, which meansthe chance their translation works being readby Muslims, is big as well. The translatorseither choose to change the term by using anappropriate term used by the majority religionor making Christianity less noticeable bygeneralizing the term in the target text. Thus,the translators cover the sense of Christianityin the original novel by applying thedomestication strategy. They incline tomaintain the ideology that is followed by themajority in the target culture. In this research,Christianity, which is shown in an expressionform, is rejected by changing it into Islamicand general form.Protecting the Target Culture’s NormsTaboo slangs do not belong only toWestern societies. Indonesia also has tabooslang that is used on informal and limitedoccasions. The problem arises when the tabooslangs make an appearance in published booksthat are bought and read by the community.The translators have to decide whether theyshould include the Western‟s taboo slangs oromit them in the books by taking into accountthe opposite norms and values that bothcultures hold. In this research, the translatorsdecide to minimalize the apparent appearanceof the Western‟s taboo slangs in their works.For instance, the translators rely on a creationstrategy that enables them to cover up the truemeanings of the source text‟s slang. Bothtranslators apply the creation strategy totranslate the term flop that refers to sexualintercourse. T1 translates it into bersenangsenang yang lebih tinggi and T2 translates itinto main-main. Both translators avoidchoosing the equivalent of a flop in the targettext. Such activity is considered indecent fromthe perspective of the target culture. Then, thetranslators create new phrases that can lead thetarget readers‟ interpretation of flop to itsintended meaning yet the translators make itless obvious.Foreignization Principle as Threats toLinguistic ImperialismThe data show that the numbers ofpreservation and naturalization strategy in the2017 version (T2) are doubled compared to the2003 version (T1). The comparison ofnaturalization strategy can be seen as follows:9

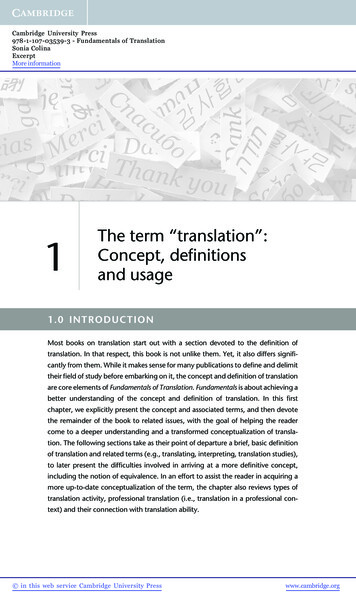

RUBIKON Volume 8/ Number 1February 2021504030T1T220100PR AD NA LI CE OM GL CW CR EQ MSFigure 1. The application of translation strategies in Of Mice and Men‟s culture-specific itemsBased on the graphic above, sometranslation strategies applied in both translatednovels experience drastic changes over time,for instance, preservation strategy, addition,naturalization, literal translation, omission,creation, and equivalent strategy. It isnoteworthy that the year when the novels weretranslated affects the trends of choosingtranslation strategies. For instance, whenalfalfa had not yet developed in Indonesia, thefirst translator who worked on the translationin the 1950s applies the omission strategy.In the comparison of preservationstrategy, the preferences of both translators areobvious. The first translator chooses tolocalize the culture-specific items; however,the second translator preserves the sourcetext‟s culture-specific items. It can be assumedthat the second translator is adopting someparts of American culture in her translation,for instance, the preservation of sir, mister,and ma’am in which these terms haveequivalents in the target text, as presented inthe first translator‟s work. The secondtranslator also tends to naturalize Englishitems that have equivalents in the targetlanguage, for instance, cream and circus. Thefirst translator chooses the items‟ equivalentsthat are included in Kamus Besar BahasaIndonesia, which are kepala susu for creamand kumidi for circus; though it has to beadmitted the equivalents are rarely used10nowadays. On the other hand, the secondtranslator chooses popular terms that fit intothe present day‟s preference, which are mostlynaturalized from the source language.The application of naturalization in themost recent novel indicates that many Englishwords have been naturalized into theIndonesian language and the words are usedwidely in Indonesian conversation. Accordingto Judickaitė (2009), this translation strategydoes bring the target readers closer to thesource culture since the original y and phonologically. Byanalyzing the comparison between T1 and T2in terms of the application of theforeignization principle, it can be concludedthat the foreign items within the original textare more preserved in the rece

Indonesian versions of Of Mice and Men from a postcolonial perspective has yet to be explored. This research aims to analyze the power inequality in translation, as seen from a postcolonial translation studies. The material objects are American novel Of Mice and Men by John Steinbeck and its Indonesian translations.