Transcription

Free-Flowing RiversSustaining Livelihoods,Cultures and Ecosystems

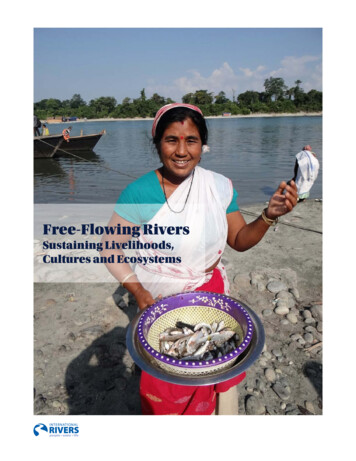

About International RiversInternational Rivers protects rivers and defends the rights of communities that dependon them.We seek a world where healthy rivers and the rights of local river communities are valued andprotected. We envision a world where water and energy needs are met without degradingnature or increasing poverty, and where people have the right to participate in decisions thataffect their lives.We are a global organization with regional offices in Asia, Africa and Latin America. We workwith river-dependent and dam-affected communities to ensure their voices are heard and theirrights are respected. We help to build well-resourced, active networks of civil society groups todemonstrate our collective power and create the change we seek. We undertake independent,investigative research, generating robust data and evidence to inform policies and campaigns.We remain independent and fearless in campaigning to expose and resist destructive projects,while also engaging with all relevant stakeholders to develop a vision that protects rivers andthe communities that depend upon them.This report was published as part of the Transboundary Rivers of South Asia (TROSA)program. TROSA is a regional water governance program supported by the Government ofSweden and managed by Oxfam. International Rivers is a regional partner of the TROSAprogram. Views and opinions expressed in this report are those of International Rivers and donot necessarily reflect those of Oxfam, other TROSA partners or the Government of Sweden.Author: Parineeta DandekarEditor: Fleachta PhelanDesign: Cathy ChenCover photo: Parineeta Dandekar - Fish of the Free-flowing Dibang River, Arunachal Pradesh.Back photo: International Rivers - Paro Chhu, Paro, Bhutan.Published December 2018Copyright 2018 by International RiversInternational Rivers1330 Broadway, #300Oakland CA 94812Phone: 1 510 848 1155www.internationalrivers.org

TABLE OF CONTENTSIntroduction4Defining a free-flowing river6Methodology to identify free-flowing rivers using global datasets8The imperative to protect free-flowing rivers9Food securityFloodsBiodiversityFresh water and water qualityHuman healthCultural, spiritual and religious contributionRecreation and eco tourismEducationSediment transport and the link to deltasClimate change, climate resilienceIn conclusion: The way forward1011131414141616171718

INTRODUCTIONFree-flowing rivers are some of the rarest andmost endangered ecosystems in the world.These unrestrained, wild rivers evoke a sense ofawe. They are a precious endangered part of theenvironment, like the Javan Rhinoceros in the wild.Today, damming of rivers has become so pervasivethat across the world only 21 rivers longer than1,000 kilometres remain undammed, retainingtheir connection to the sea.1 Of these, 40 percentare concentrated in the Amazon and far eastRussian river systems.Globally, there are 58,519 large and countlessthousand smaller dams situated on 65 percentof the world’s rivers, including the eight mostbiogeographically diverse basins.2 50 percent of theworld’s available freshwater and 25 percent of theglobal sediment load is trapped behind dam walls.3“Identify and conserve a globalnetwork of free-flowing rivers:Dams and dry reaches of rivers preventfish migration and sediment transport,physically limiting the benefits ofenvironmental flows. Protectinghigh-value river systems from development ensures that environmental flowsand hydrological connectivity aremaintained from river headwaters tomouths. It is far less costly and moreeffective to protect ecosystems fromdegradation than to restore them.”Historically, the idea of a river not meeting the seapermanently, or for major parts of the year, wasperceived as a tragedy by many cultures across theworld. However in current times there is sadly littleconcern about such developments.— Brisbane Declaration, 2007Today, in spite of this, it is being proposed to dammost of the final remaining free-flowing rivers ofthe world: in a cascade of dams in many cases.This would include tributaries of the Brahmaputrain China, Bhutan and India, tributaries of the Ganges in India and Nepal, the Irrawaddy in Burma,tributaries of the Amazon in South America, theVjosa in Albania in addition to several dams inthe Balkan peninsula in Eastern Europe, and theLuangwa in Zambia, to name just a few.While these rivers have spectacular scenic andrecreational value, they are also the lifeblood ofThe sacred Rongyoung River in Sikkim, IndiaPhoto: Gyatso Lepcha1. ivers2. Nilsson et al., 2005, Fragmentation and Flow Regulation of theWorld’s Large River Systems, Science.3. Danielle Perry, 2017, The uneven geography of river conservation inthe U.S: Insights from the application of Wild and Scenic Rivers Act.4

The Vjosa River in Albania Photo: Gregor Subicthe communities who depend on them in myriadways: they provide and support fish, farms, prayersand songs. At the same time, their unmatched rolein safeguarding biodiversity, protecting deltas fromerosion, mitigating the impacts of climate change,and providing unsurpassed educational opportunities for future generations to learn about aquaticbiodiversity, the importance of sediments, etc,gives each free-flowing river a global significanceand importance too.Several countries have passed some form oflegislation to protect free-flowing rivers, but sadlysuch protection is often missing in the placeswhere it is needed the most. Moreover globalinformation, coordination and frameworks are alsolacking. There is no global inventory of free-flowingrivers, nor a commonly accepted methodology toidentify them. Neither is there a platform to shareinformation and analysis regarding the diversebenefits of free-flowing rivers, novel ways toprotect them, lessons learned and to rally fortheir protection. In spite of this, more and morecommunities and organisations across the worldare coming together organically to protect theirfree-flowing rivers, valuing them for their uniquelylocal and global importance.The era of large dams is over, with overwhelmingevidence showing their excessive costs to communities, and the planet’s life support systems.Inefficiencies, time delays and cost overruns ofmajor infrastructure projects like dams have beenextensively documented. In the era of climatechange, protecting the last remaining freeflowing rivers makes ecological, economic, socialand cultural sense. Moreover, efforts across theworld have clearly demonstrated that restoringdamaged ecosystems is more effective thanengineering solutions, and so protecting healthyecosystems such as free-flowing rivers is one of themost efficient initiatives in times of climate change.The time is thus ripe to devise strategies,campaigns and energy to protect and conservefree-flowing rivers.5

DEFINING A FREE-FLOWING RIVERAlthough the concept of a free-flowing river isan intuitive one to grasp, yet the vast scope of afree-flowing river makes for a complex definition.One of the reasons for this is the intricate interconnectivity of river systems - the way they encompassliving and non-living entities, water and sediment,crossing regional and international borders andtranscending cultures and eco-regions. This naturalfact emphasises the necessity to ensure the freedom of a river to flow at all scales: lateral (channelto floodplains), longitudinal (headwaters to theocean/bigger river/lake/plains), vertical (surface togroundwater) and temporal (flow variability acrossa timescale). It also includes secure headwaterregions, connected riparian areas and floodplains,intact features like ripples, pools and meanders,swamps, bayous, marshes, mangroves, etc.encountering any dams, weirs or barragesand without being hemmed in by dykesor levees.”4 “A free-flowing river or stretch of riveroccurs where natural aquatic and riparianecosystem functions and services are largely unaffected by anthropogenic changesto fluvial connectivity, allowing an unobstructed exchange of material, species andenergy within the river system and beyond.Fluvial connectivity encompasses longitudinal (river channel), lateral (floodplains),vertical (groundwater and atmosphere)and temporal (intermittency) componentsand can be compromised by infrastructureor impoundments in the river channel,along shorelines, or in adjacent floodplains; hydrological alterations of river flowdue to water abstractions or regulation;and changes to water chemistry that lead toecological barrier effects caused by pollution or alterations in water temperature.” 5Free-flowing rivers are synonymous with a healthy,connected, living river ecosystem.At the same time, free-flowing rivers are not necessarily completely untouched and devoid of humanpresence. Nor do they exist as natural museumswith restricted access. Many healthy, connectedrivers have been used by local communities andindigenous groups for millennia, and provideunsurpassable cultural and livelihood value tothose communities. Free-flowing rivers are the“freshwater equivalent of wilderness areas” and yetthey also support rich livelihoods for communities.Definitions of free-flowing riversTwo definitions of free-flowing rivers, developed bythe WWF, are useful to deepen our understanding. “Free-flowing rivers are any rivers that flowundisturbed from their source to mouth,at either the coast, an inland sea or at theconfluence with a larger river, withoutLegislation around the world which aims to protectfree-flowing rivers or riverine stretches definesthem differently, depending on the scope of thelegislation. For example, New South Wales, a statein Australia, defines wild rivers thus: “wild riversare rivers that are in near-pristine condition interms of animal and plant life and water flow, andare free of the unnatural rates of siltation or bankerosion that affect many of Australia’s waterways.”6The Wild and Scenic Rivers Act of the USA classifiesriver areas into wild, scenic and recreational areas.The Canadian Heritage Rivers Act aims to protect4. http://wwf.panda.org/wwf -ecological-necessity5. 35/files/original/WWF Free Flowing Rivers Fact Sheet.pdf?14726507146. vers.htm6

rivers of remarkable social value, some of whichmay be dammed, while Sweden and Norway haveendeavoured to protect rivers representing eachecoregion of the country.Freedom to flowIn a more fundamental paradigm shift, several countries across the world are attempting toacknowledge and safeguard the “rights” of riversthemselves, and a central right is the “Right toFlow”. This movement is developing and growingorganically in different corners of the world, fromdeveloped and developing countries alike, fueledby governments, indigenous groups and civilsociety, and often manifested in and throughconstitutional provisions. Countries such as NewZealand, Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, Mexico,India, Serbia and Ethiopia are experimenting withdifferent forms of intervention to protect not onlyanthropocentric “ecosystem goods and services”of rivers, but also their intrinsic values.The Amazon Mainstem in Peru. Photo: Parineeta Dandekar7

METHODOLOGY TO IDENTIFY FREE-FLOWINGRIVERS USING GLOBAL DATASETSDespite their critical importance, there is no globalinventory of free-flowing rivers. However, severalorganisations and universities have come togetherin a bid to develop such an inventory, as well as amethodology to identify free-flowing rivers througha global dataset.7 This methodology is based onidentifying “Pressure Indicators” which affect ariver’s connectivity at any scale.“While a global academic methodologycan identify large free-flowing rivers,ideally communities would cometogether to identify smaller freeflowing rivers in their regions. Themethodology to identify free-flowingrivers is as yet hazy and thus the role ofcommunities in bringing more suchrivers into the spotlight is crucial.”Pressure Indicators identified in this effort are:Degree of fragmentation: This indicator mapshow large dams affect river connectivity longitudinally. This includes only large dams currentlyand is based on the global large dam database,developed by experts in the area.Degree of regulation: This calculates how much aparticular dam affects annual average downstreamflow, which relates to lateral, longitudinal, verticaland temporal connectivity. This is also based onthe global dam database.Road density: This indicator looks at how roadsaffect lateral connectivity when developed over7. dplains or when a river passes throughculverts. This is measured through a databaseof the world’s roads called GRIP.Urban areas: This examines how lateral connectivity can be affected by cities and other infrastructuredeveloped in floodplains. This indicator is measured using satellite imagery of nightlight intensity.Consumptive water use: This is measured bywater abstraction and consumption data availablethrough WaterGAP8, and represents how lateral,vertical and temporal connectivity can be disruptedthrough extracting too much water by changinggroundwater aquifers.It is clear that even when fully developed, theseindicators will mostly be applicable for biggerrivers with large, documented infrastructure.Thus there is a need for local community-basedorganisations and researchers to come together toidentify, document and protect smaller free-flowing rivers in their area, which are facing challengeslike embankments, dams, hydropower projectswith diurnal water fluctuations etc.Certain questions also need to be addressed, forexample: How should a river with small, community-owned water harvesting structures across it beclassified? How to classify micro hydel projects andsmall community-made diversions? How shouldrivers which have dams only in the headwaters oronly near the delta be classified? What should bethe length of a river to be considered free-flowing?All of these questions require further collectivediscussions and work by community groups,academics and researchers.8. Water GAP is a global water database calculating flows andstorages.8

THE IMPERATIVE TO PROTECT FREE-FLOWING RIVERSThe Okavango Delta in Botswana Photo: Teo Gomez Wikimedia CommonsHealthy rivers play a central role in several ecosystem processes. Scientists have proven timeand again that the natural flow regime of a riveris the ‘master variable’ driving the diversity andvitality of river and floodplain ecosystems.9 At thesame time, the natural flow regime is the feature ofrivers which is subject to most interference today.Land-use change, river impoundment, surfaceand groundwater abstraction and basin transfersprofoundly alter natural flow regimes.109. Poff et al, 2009, Ecological responses to altered flow regimes:a literature review to inform the science and management ofenvironmental flows, Freshwater Biology. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/227644884 Ecological Responsesto Altered Flow Regimes A Literature Review to Informthe Science and Management of Environmental Flows ;Power et al., 1995; Walker, Sheldon & Puckridge, 1995.10. Arthington et al., 2009, Preserving the biodiversity and ecological services of rivers: new challenges and research opportunities,Freshwater Biology https://www.researchgate.net/publication/48380733 Preserving the biodiversity and ecological services of rivers New challenges and research opportunities2007Not surprisingly, all of the accepted five majorcategories of threat to fresh waters – overexploitation, water pollution, fragmentation, destruction ordegradation of habitat and invasion by non-nativespecies - are directly linked to the modification ofriver flows.11Not only is the natural flow regime importantfor ecosystems and biodiversity, it is the veryfoundation of a robust, adaptable river in the eraof climate change. The natural adjustments of ahealthy river, such as lateral migration of channels,interactions between the streambed, floodplainand riparian zone, etc, allow rivers to absorbdisturbances and buffer surrounding areas fromthe impacts of floods and anthropogenic effects.This makes free-flowing rivers more capable ofadapting to, and mitigating the effects of, climatechange, as opposed to dammed rivers.1211. ibid; Malmqvist & Rundle, 2002; Dudgeon et al., 2006.12. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/258181492 Climatechange and the world’s river basins Anticipating management options9

Free-flowing, healthy, connected rivers whichfollow their natural rhythm of flow provide a rangeof services free of cost to the community. If theseservices are compared with the costs of restoringimpaired rivers, the incomparable intergenerationalimportance of healthy, free-flowing rivers can befully understood.Services provided by free-flowing riversSome important services provided by healthy,flowing rivers are outlined below.as the floods recede, the same land is used to growsorghum and millets and then as the land dries up,livestock is grazed there.15FisheriesOne of the most important ecosystem servicesaffected by damming rivers is riverine fisheries.Across the world, indigenous and marginalisedcommunities have depended on riverine capturefisheries. Moreover, this cannot be compared tothe fisheries in dam reservoirs which include contracts, seeding, species composition change, etc.Food securityThe Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MEA)13was initiated in 2001 to assess the consequencesof ecosystem change for human well-being, thescientific basis for action needed to enhance theconservation and sustainable use of those systemsand their contribution to human well-being. In2005 it highlighted the crucial importance of freshwater ecosystems, as well as the threats they face.According to the MEA, freshwater ecosystems arethe backbone of global food production based onartisanal and commercial fisheries, aquaculture,floodplain recession agriculture and animal husbandry. The fibres and biochemicals derived fromriparian and wetland plants are critically importantto human welfare and livelihoods in many partsof the world, as are other regulating and culturalservices.Today, 60 million people live in the LowerMekong Basin in South East Asia, and 80 percentof those people rely directly on the river systemfor their food and livelihoods.14 Sadly these peopleand their livelihoods are now at the mercy of theMekong dams.Fishing in the River Senegal, West Africa Photo: livelihoods.euFor example, in India, it is estimated that approximately 10 million fisherfolk or more depend onriverine capture fisheries, and this sector is severelyimpacted by damming, resulting in change inspecies composition, near extinction of localspecies, drastic fall in migrating species, etc.16“To me, it’s an environmentalinjustice. Many people havebenefited from the developmentand changes at the expense of theresource and the tribes. It’s only rightto restore the fishery back to us.”In the Senegal River Basin of West Africa, when itfloods from July to October, four hundred thousand hectares of floodplains are inundated, andthe enriched floodwaters support 10,000 fisherfolk,who catch 30,000 tonnes of fish per year, a majorsource of protein for the local communities. Later,13. Millenium Ecosystem Assessment, 14. Orr et al 2012, Dams on the Mekong River: Lost fish protein and theimplications for land and water resources, Global EnvironmentalChange.— Klamath Tribes Chairperson Don Gentry,speaking about the Klamath dams15. Parviz Koohafkan, Forgotten Agricultural Heritage: Reconnectingfood systems and sustainable development, Routledge, 2017.16. e-775810

Fishing at Khone Falls, Mekong region, Laos Photo: National GeographicThe negative impacts of dams on fisheries andfish diversity have been the driving factor behindseveral dam decommissioning efforts in countrieslike the USA. One of the biggest sanctioned damremoval projects in the USA is the series of fourhydropower projects on the Klamath River, whichwill free more than 640 kilometres of the river forpeople and fish. This is important not only for theChinook and Steelhead Salmon, but also for thelocal Klamath Indian tribes.In India, a study comparing the Aghanashini, afree-flowing river, and its dammed counterpart,the Sharavathi, both in Karnataka, revealed that the“Aghanashini Estuary supports 20 fishing villages,while there are only 10 fishing villages in Sharavathi Estuary. Fisherfolk in Aghanashini are morethan 6,000, while Sharavathi estuary supports only283 fisherfolk. Gathering of edible bivalves, a majoreconomic activity in Aghanashini estuary has goneextinct in Sharavathi.”17In Japan, the local fishing community cametogether to advocate for the removal of the AraseDam in Kumamoto Prefecture, as it directly17. and-beyond/affected the fishing of a migrating fish called Ayu,as well as eels and shrimps. This will be the firstdam to be decommissioned in Japan.18In the Mekong region, the damming of the mainstem Mekong and its tributaries is directly linked tothe fisheries-related livelihoods of over 60 millionpeople. These hydropower dams are creating a“food security crisis”.19 In the Amazon, dams ontributaries are already negatively affecting fishand livelihoods.20FloodsIn many ancient cultures, from India to Egypt,floods were heralded and celebrated as the harbingers of fertility, soil moisture and rejuvenation. Ahealthy river connected with its floodplains deposits silt and delivers a push of nutrients. As thefloods recede, floodplains are used for recessionagriculture in many parts of the world. For example, in the free-flowing Okavango River Delta inBotswana, floodplain recession farming, knownas Molapo, results in much higher yields of maizedespite low inputs of fertilisers, due to fertile silt18. l19. Stone, 2016, Dam-building threatens Mekong fisheries, Science.20. n11

The Okavango Delta in Botswana Photo: botswanatourism.co.bwand soil moisture. About 25 percent of agriculturein the Okavango Delta depends on riverine floodpulses and exposed floodplains.21Ancient Egyptians celebrated thefloodings of the Nile and evenworshipped a Nile Flood God, tocelebrate life-giving silt and waters.After the completion of the AswanDam and later developments, the NileDelta suffered immensely due to drastic reduction of freshwater and silt, asdid estuarine and marine fisheries.as quickly. The root systems of riparian forest andaquatic vegetation keep the pores of the soil open,so that two to three times more water can infiltratethe soil compared to lands used for cultivation orgrazing.22In several countries, reconnecting rivers to theirfloodplains, bringing down dykes and embankments, and dechannelising rivers is being seen asa cost effective and efficient mode of flood control,moving away from infrastructure-heavy flood“In the Mekong Delta, Tonle BassacRiver and its floodplains in AngkorBorei, Cambodia, allow floods tospread and silt to settle over vast areas.This has resulted in a flood recessionrice farming so rich that it is believedthat this system, depending on the“exceeding fertility of the silt broughtby natural river floods”, played asignificant role in the early historyand culture of the Mekong Delta.”At the same time, a floodplain regulates the river.An undeveloped, vegetated floodplain reduces theforce, height and volume of floodwaters by allowing them to spread out horizontally and relativelyharmlessly across the floodplain. Water that floodsinto vegetated floodplains is soaked up by the“sponge” of floodplain wetland soils and streamside forest leaf litter, which then re-enters the mainchannel slowly. Healthy riparian areas providenumerous barriers against moving water, whichslows it down so water does not flow downstream21. Molapo Farming in the Okavango Delta, rming%20in%20the%20Okavango%20Delta.pdf— Fox and Ledgerwood 19992322. eet2.pdf23. https://www.jstor.org/stable/42928445?se- q 1#page scan tabcontents12

Saving the biodiversity rich Karnali River in Nepal Photo: Waterkeeper Alliancecontrol measures. The Netherlands, a countrywhich sits below sea level, and thus is extremelyvulnerable to sea level rise and floods, is emergingas the global leader in the concept of giving“Room for Rivers”.24 The same country was aleader in building dykes and embankments ina previous era.Biodiversitycontain only around 0.01 percent of the world’swater and cover only about 0.8 percent of theearth’s surface. Almost 10 percent of the globallydescribed species call freshwater ecosystems theirhome. An additional 50,000–100,000 species alonemay live in ground water.25Impoverished biodiversity means decreased foodproduction and food security, loss of resources forindigenous medicine, diminished supplies of rawFree-flowing rivers are the true safety vaultsof biodiversity, much of which is still beingdiscovered and documented.“The Vjosa represents one of the lastintact large river systems in Europe,hosting all different types of ecosystems: from the narrow gorges in theupper part to the wide braided riversections in the middle part to the nearnatural delta at the Adriatic Sea.The Vjosa is a European treasure.Its greatest value lies in its uncompromised intactness. The dams woulddestroy this unique ecosystem and itshigh potential for sustainable naturetourism in the future.”Freshwater ecosystems, including free-flowingrivers, harbour the highest diversity and have thehighest proportion of species threatened withextinction, as compared to other ecosystemsstudied under the MEA.Freshwater habitats support a disproportionaterichness of plants and animals. Over 10,000 fishspecies live in fresh water, making up approximately 40 percent of global fish diversity and onequarter of global vertebrate diversity. Whenamphibians, aquatic reptiles (crocodiles, turtles)and mammals (otters, river dolphins, platypus) areadded to this freshwater-fish total, then as much asone-third of all vertebrate species in the world arefound in freshwater. Yet surface freshwater habitats24. https://www.ruimtevoorderivier.nl/english/— www.balkanrivers.net25. D Dudgeon et al., 2006, Freshwater biodiversity: importance,threats, status and conservation challenges, Cambridge Philosophical Society.13

materials for new pharmaceuticals and biotechnology and degraded water quality.26Free-flowing rivers like the Karnali in Nepal, theIrrawaddy in Burma, the Mura in Europe, thePascagoula in the USA and the Luangwa in Zambiasupport an amazing diversity of plant and animalspecies, and play a central role in their protection.“Flow alterations have resulted in apandemic breakdown of ecosystemintegrity, thereby affecting the risk ofacquiring infectious diseases, throughtheir impact on the biodiversity of infectious agents, reservoirs and vectors.The net result is that human well-being- whether from disease or a state ofhealth - is increasingly compromised.”— Naiman and Dudgeon 201027Fresh water and water qualityA healthy undisturbed river with its range ofbiodiversity ensures good water quality too. Forexample, freshwater mussels and bivalves, whichare excellent natural filters, are affected directly byinfrastructure. A single oyster thriving in a healthycreek or estuary can filter three litres of water in anhour.28 Oyster reefs function as natural filter banksof rivers.Natural riparian areas connected to rivers areextremely efficient at trapping sediments. Somestudies estimate that natural riparian areas capture84-90 percent of sediments from cultivated fields.They are also efficient filters of nutrients likenitrates, phosphates, sulfur, etc which driveeutrophication of rivers and lakes and directlyaffect water availability.29The flow of a river or stream is directly linked to theamount of dissolved oxygen in water, which is one26. an-health27. ns/Naiman 2011 - Global Alteration of Freshwaters Influences on Human and Environmental Well-Being.pdf28. /29. https://pubs.ext.vt.edu/content/dam/pubs ext vt edu/420/420151/420-151 pdf.pdfof the important indicators of water quality. Lowflow and stagnancy result in low dissolved oxygen.Riparian forests also play a role in maintainingwater temperature, which in turn affects oxygenconcentration. Lower temperatures support moreoxygen in water and are conducive to specieslike trout and salmon. Intact sandy river banksact as natural water filters, maintaining goodwater quality.Human healthFlow alterations of rivers significantly reduce freshwater biodiversity, modify disease spreading vectorabundance and pathways of disease transmissionby impacting habitat, temperature and biotic factors. Reservoirs and stabilised flow regimes lead toan increase in disease vectors like blackflies, snailsand mosquitoes.The simplification of the natural flow regime,creation of habitats such as canals, ditches, ponds,and reservoirs, and the simplification of naturalspecies assemblages allows mass proliferation ofdipteran and snail vectors for parasites andmodification of bacterial and viral communities.In contrast, healthy, restored rivers are associatedwith a range of social benefits, including physicaland mental wellbeing.30Cultural, spiritual and religious contributionFlowing river

ocean/bigger river/lake/plains), vertical (surface to groundwater) and temporal (flow variability across a timescale). It also includes secure headwater regions, connected riparian areas and floodplains, intact features like ripples, pools and meanders, swamps, bayous, marshes, mangroves, etc. Free-flowing rivers are synonymous with a healthy,

![Ecosystems 5E Lesson Plan for Grades 3-5 [PDF]](/img/22/ecosystems-lesson-plan-gg.jpg)