Transcription

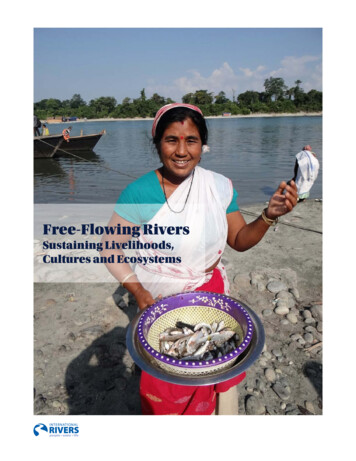

Sustaining livelihoodsto leave no one behindENDING EXTREME POVERTY IN RURAL AREASENDINGEXTREME POVERTYIN RURAL AREASENDINGEXTREME POVERTYIN RURAL AREASSustainable Development Goal 1, ending poverty in all its forms,everywhere, is the most ambitious goal set by the 2030 Agenda. This Goalincludes eradicating extreme poverty in the next 12 years, which willrequire more focused actions in addition to broad-based interventions.The question is: How can we achieve target 1.1 and overcome themany challenges that lie ahead? By gaining a deeper understanding ofpoverty, and the characteristics of the extreme rural poor in particular,the right policies can be put in place to reach those most in need.This report presents the contribution that agriculture, food systemsand the sustainable use of natural resources can make to securing thelivelihoods of the millions of poor people who struggle in our world.Sustaining livelihoodsto leave no one behindISBN 978-92-5-131027-497 8 9 2 5 13 1 0 2 7 4CA1908EN/1/10.18FAO

This report is primarily directed towards decision-makers responsible fordesigning and implementing national policies and programmes to achieveSustainable Development Goal 1 (No poverty) and in particular Target 1.1 oneradicating extreme poverty by 2030. It will also be of value to developmentpartners, public and private actors, including investors, researchers andtechnical practitioners, involved in the broad area of food and agriculture,and rural development. Building on FAO’s mandate to achieve Zero hunger,No poverty and sustainable management of natural resource, this publicationpresents how agriculture, food systems and sustainable management ofnatural resources can accelerate the achievement of Target 1.1 in rural areas.

ENDINGEXTREME POVERTYIN RURAL AREASSustaining livelihoodsto leave no one behindPrepared byAna Paula de la O Campos, Chiara Villani,Benjamin Davis and Maya TakagiFOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONSRome, 2018

Required citation:De La O Campos, A.P., Villani, C., Davis, B., Takagi, M. 2018.Ending extreme poverty in rural areas – Sustaining livelihoods to leaveno one behind. Rome, FAO. 84 pp. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.The designations employed and the presentation of materialin this information product do not imply the expression of anyopinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and AgricultureOrganization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legalor development status of any country, territory, city or area orof its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiersor boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products ofmanufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does notimply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO inpreference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned.The views expressed in this information product are those of theauthor(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of FAO.ISBN 978-92-5-131027-4 FAO, 2018Some rights reserved. This work is made available under the CreativeCommons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO licence(CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; igo/legalcode).Under the terms of this licence, this work may be copied,redistributed and adapted for non-commercial purposes, providedthat the work is appropriately cited. In any use of this work, thereshould be no suggestion that FAO endorses any specific organization,products or services. The use of the FAO logo is not permitted.If the work is adapted, then it must be licensed under the same orequivalent Creative Commons license. If a translation of this workis created, it must include the following disclaimer along with therequired citation: “This translation was not created by the Foodand Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). FAO isnot responsible for the content or accuracy of this translation.The original [Language] edition shall be the authoritative edition.Disputes arising under the licence that cannot be settled amicably willbe resolved by mediation and arbitration as described in Article 8 of thelicence except as otherwise provided herein. The applicable mediationrules will be the mediation rules of the World Intellectual PropertyOrganization http://www.wipo.int/amc/en/mediation/rules andany arbitration will be in accordance with the Arbitration Rules of theUnited Nations Commission on International Trade Law (UNCITRAL).Third-party materials. Users wishing to reuse material fromthis work that is attributed to a third party, such as tables, figuresor images, are responsible for determining whether permissionis needed for that reuse and for obtaining permission from thecopyright holder. The risk of claims resulting from infringement of anythird-party-owned component in the work rests solely with the user.Sales, rights and licensing. FAO information products areavailable on the FAO website (www.fao.org/publications) and canbe purchased through publications-sales@fao.org.Requests for commercial use should be submitted via:www.fao.org/contact-us/licence-request. Queries regarding rightsand licensing should be submitted to: copyright@fao.org.

ContentsAcknowledgementsvExecutive summaryvii1. Introduction12. Understanding the extent ofthe challenge in rural areas33. Characterizing therural extreme poor:what challenges do they face?124. Ending extreme povertyin rural areas: someimportant considerations305. Key elements incountries’ strategies forending extreme poverty386. Sustaining livelihoods:how can agriculture, foodsystems and sustainablemanagement of naturalresources acceleratethe achievement ofTarget 1.1 in rural areas?51References60iii

ENDING EXTREME POVERTY IN RURAL AREASFiguresFigure 1. Comparison of the headcount ratios of MPI poor,MPI destitute, and income extreme poverty measureof USD 1.90/day6Figure 2. Share of the population by welfare andresidential sector8Figure 3. Share of extreme poor, moderate poor andnon-poor in urban and rural areas8Figure 14. Coverage of social protection and labour in totalpopulation (%)25Figure 15. Poverty reduction for Indigenous vs non-indigenous27Figure 16. Top country concentration of extreme poverty inLICs and LMICs32BoxesFigure 4. Changes in proportions of rural and urban extreme poor,moderate poor, and non-poor, in total population ofselected countries, by region, 1990s–2010s9Box 1. What do China and Brazil have in common?3942Figure 5. What happens to people who escapeextreme poverty11Box 2. Investing in food systems and promoting skillsdevelopment for better employment opportunitiesin rural areasFigure 6. Mean consumption for the developing world11Box 3. Cash transfers: myths vs. reality44Figure 7. Undernourishment and extreme povertyrates generally correlate at the country levelBox 4. Linking social assistance to development interventions4613Box 5. India: the National Rural Livelihoods Mission48Figure 8. Prevalence of stunting in children under five,by household income15Box 6. PROEZA: an integrated approach to fight extremepoverty and climate change57Figure 9. Types of agroecological systems and levelsof urbanization16Figure 10. Share of rural workers by employment sectorand welfare17TablesFigure 11. Share of total income from main income generatingactivities (Africa) by expenditure quintile18Figure 12. Share of total income from main income generatingactivities (Non -Africa) by expenditure quintile19Figure 13. Income from fisheries in Bangladeshby income group22ivTable 1. Proportion of smallholders (rural areas only)that are poor21Table 2. Distribution of rural people living on less thanUSD 1.25 per day and residing in or aroundtropical forests and savannahs21

AcknowledgementsTPanel of internal reviewershis report was preparedby the FAO StrategicProgramme to Reduce RuralPoverty (SP3). Under theoverall guidance of Kostas Stamoulis(ADG-ES), the direction of thepublication was carried out by AnaPaula de la O Campos, Chiara Villani,Benjamin Davis and Maya Takagi.This report has been possible thanksto the contributions of the severaltechnical areas and regional and countryoffices of FAO, as well as the valuablecontribution of external peer reviewers.Ould Ahmed Abdessalam (FAORNE),Jacqueline Alder (FIAM), AlejandroAcosta (AGAL), Melisa Aytekin(FAORAF), Manuel Barange (FIA),Pierre Marie Bosc (CBL), Diop Bouna(AGAH), Clayton Campanhola (SP2),Marco Sanchez Cantillo (ESA),Francisco Carranza (DPSL), ReneCastro (CBD), Vito Cistulli (ESP),Michael Clark (ESD), Piero Conforti(ESS), David Conte (SP3), IleanaGrandelis (ESP), Maja Gravilovic(ESP), Driss Haboudane (AGE,FAO-IAEA), May Hani (ESP),Guenter Hemrich (ESN), MsahiroIgarashi (OED), Justin Jannolo (ESP),Akiko Kamata (AGAH), ElizabethKoechlein (ESP), Maria HernandezLagana (CBL), Erdgin Mane (ESP),Alberta Mascaretti (TCIA), NormanMesser (TCI), Jaimie Morrison(SP4), Eva Muller (FOA), Clara Park(FAORAP), Francesco Pierri (DPSA),Pamela Pozarny (FAORAF), AhmedRaza (ESN), Beate Scherf (SP2),Libor Stloukal (ESP), Andrew Taber(FOA), Carlos Tarazona (OED),FAO contributorsVerdiana Biagioni Gazzoli, NigussieTefera, Natalia Winder Rossi,Jim Hancock, Julius Jackson, AhmadSadiddin, Raffaele Bertini, and Sara Vas.External contributorsSubramanyam Vidalur Divvakar(independent consultant), andJulian May, Anthea Dallimoreand Darryn Durno from SADCResearch Centre, South Africa.v

ENDING EXTREME POVERTY IN RURAL AREASFlorence Tartanac (ESN), LisaVan Dijck (ESP), Samuel Varas(CIO), Verena Wilke (AGP).Administrative supportPanel of external reviewersSupport for report production wasprovided by Chiara Villani, DeniseMartinez, Jennifer Gacich (editing),and Studio Bartoleschi (layout).Rosa Capuzzolo, Isabella Clemente.Aude de Montesquiou, AlessandraMarini, Ruth Hill and AmbarNarayan from the World Bank Group(WBG). Andrew Shepherd andVidya Diwakar, from the ChronicPoverty Advisory Network (CPAN),Oversees Development Institute(ODI). Amson Sibanda from UnitedNations Department of Economicand Social Affairs (UNDESA).Stephen Devereux, from the Institutefor Development Studies (IDS).Jose Cuesta from the United NationsChildren’s Fund (UNICEF) InnocentiResearch Center. Leopoldo Tornarollifrom Centro de Estudios Distributivos,Laborales y Sociales (CEDLAS).Subramanyam Vidalur Divvakar(independent consultant). Fabio VerasSoares from International Policy Centerfor Inclusive Growth (IPC-IG).vi

ExecutivesummarySUnderstanding the challengeof ending extreme povertyustainable DevelopmentGoal 1, ending poverty inall its forms, everywhere,is the most ambitiousgoal set by the 2030 Agenda.This Goal includes eradicatingextreme poverty in the next12 years. The question is: Howcan we achieve target 1.1 andovercome the many challengesthat lie ahead? By gaining adeeper understanding of poverty,and the characteristics of theextreme rural poor in particular,the right policies can be put inplace to reach those most in need.Agriculture, food systems andthe sustainable use of naturalresources are key to securing thelivelihoods of the millions of poorpeople who struggle in our world.In 2015, about 736 million people –about 10 percent of the globalpopulation – were living in extremepoverty. Though considerable progresshas been made over the last threedecades in reducing extreme povertyand overall poverty, the welfare levelof those who have remained at thebottom of the income or consumptiondistribution has stayed the same.Those who have been “left behind”face greater vulnerabilities andstructural constraints, which preventthem from benefiting from overalleconomic growth and development.The extreme poor are defined asthose individuals earning less thanUSD 1.25 a day. However, extremepoverty is complex. It is revealedthrough social marginalization andexclusion, different manifestationsof malnutrition, poor livingconditions, lack of access to basicservices, resources and employmentopportunities, and more. Often, thevii

ENDING EXTREME POVERTY IN RURAL AREASNumerous constraints however,impede their economic inclusion invarious sectors, such as insufficientaccess to basic infrastructure(e.g. water, electricity, sanitation,and roads), and inadequate access topublic services (e.g. health, education,connectivity, and markets).rural extreme poor (like the urbanpoor) are “hidden” in non-poorfamilies due to intra-householddynamics and inequality, whichis the case for many rural womenand children. Multidimensionalpoverty measures help provideinsight into the varying degrees ofdeprivation and vulnerability of theextreme poor, thus complementingincome and consumption-basedpoverty measures.There are also great disparitiesamong the extreme poor inrural areas. The rural extremepoor are often geographicallyconcentrated in marginal ruralareas – e.g. high mountain, pastoral,arid, rainforest jungle, small islands– with low population densities,poor agroecological endowments,limited access to markets andfew sources of employment.Investments in infrastructure andbasic services often do not reachthese more isolated areas, whichtend to be more disaster-prone.In contrast, extreme poverty is“individualized” in more favourableareas – with good agroecologicalconditions and connections todynamic products and labourMost of the extreme poor – about80 percent – live in rural areas.The rural extreme poor are differentfrom the urban extreme poor andthe non-poor. Their incomes dependgreatly on agricultural activities,either from work on their farms,or agricultural wage employment.It is this reliance on agriculture thatmakes the rural extreme poor highlyvulnerable to climatic shocks andweather events. While agricultureplays a big role in their income andfood security, the rural extreme pooralso diversify their sources of incomein other non-agricultural activities.viii

Key elements incountries’ strategies forending extreme povertymarkets. The extreme poor in theseareas – including rural youth, theelderly, and people with disabilities– have lower asset endowments(land, education, social capital),and fewer opportunities to increasethe returns on those endowments.Therefore, strategies to eradicateextreme poverty need to considerthe specific contexts and needs ofthe different rural extreme poor.Going the extra mile to reach therural extreme poor is not only acrucial factor in the success of SDG1,but it will also help to prevent crises,conflict and social tensions, makingpopulations more resilient to climaticshocks, providing economic alternativesin rural areas, and decreasing incomeand non-income inequality.Extreme poverty, hunger andundernourishment often go handin hand. Extreme poverty influenceshunger and nutritional status,affecting the ability of individualsand households to access foodthrough purchase or production.Extreme poverty is also linkedto low access to essential healthservices and basic infrastructure,which are fundamental for foodsecurity. At the same time, hungerand undernourishment affectthe future of young generations,causing learning difficulties, poorhealth, and lower productivityand earnings over a lifetime.A fundamental preconditionfor ending extreme poverty iscountries’ commitment. A sharedcommitment throughout societyis needed to address the rootcauses of extreme poverty, such asunequal access to resources, genderinequality, and social discrimination.Effective political leadership is akey factor in successful povertyreduction strategies. This entails:providing clear policy direction andadequate means of implementation;strengthening and creating effectiveand democratic institutions; creatingix

ENDING EXTREME POVERTY IN RURAL AREASAnother key factor in extremepoverty eradication is investing inboth social and productive capitalat local, sub-national and nationallevels. Most successful experiences ofeffective poverty reduction from the1960s to the present have involvedsubstantial investments in rural areas,such as in infrastructure, basic services,health, education, and more recently,in social assistance. Social protectionin particular is now recognized as acritical strategy for reducing poverty,hunger and promoting economicinclusion, particularly among thepoorest. Social assistance programmesand non-contributory programmes incash or in-kind can provide regularand predictable support to extremepoor and vulnerable people.incentives for multi-sectoralcoordination; as well as monitoringand evaluating progress to learn fromexperiences and improve strategies.The first step in ending extremepoverty is stimulating pro-pooreconomic growth and incomegenerating opportunities.This means fostering a patternof growth and structural changethat generates employment wherethe majority of people living inpoverty work. While agricultureis the main source of food andincome for the rural extreme poor,diversification is also an importantstrategy to end extreme poverty.Diversification helps generate incomefor non-agricultural activities forthose rural extreme poor who cannotmove out of poverty by specializingin agriculture. Examples includepromoting participation in off-farmactivities, such as food transformation,processing and packaging, particularlyin more favorable rural areas, andactivities outside the food system,such as environmental services.A third essential element forextreme poverty eradication issetting up dedicated interventionsto reach the poorest of the poor.In recent years, poverty reductionhas started to stagnate both in poorand middle-income countries dueto the global economic slowdownx

Sustaining livelihoodsthrough agriculture, foodsystems and the sustainableuse of natural resourcesand conflict, with those still leftbehind becoming increasinglyharder to reach. The extreme poorare highly vulnerable to shocks andrisks related to conflict and climatechange, yet the coverage of bothcontributory and non-contributorysocial protection and financialservices is often limited in rural areas,leaving poor households without aminimum income or mechanismsto manage risks and shocks.Agriculture, food systems and naturalresources can contribute to reachingTarget 1.1 through: (1) ensuring foodsecurity and nutrition; (2) promotingeconomic inclusion; (3) fosteringenvironmentally sustainable livelihoods;and (4) strengthening resilienceagainst shocks as well as restoringlivelihoods after shocks occur.Recognizing the need to betterarticulate and coordinate the differentpolicies and actions aimed at reducingpoverty, countries such as Chinaand Brazil have opted to implementmore dedicated and integratedinterventions which address thespecific needs of the poorest and theirchallenges. These country examplesdemonstrate how policy coherenceand the multisectoral coordinationof social and economic sectors canenhance the impact of povertyeradication policies and programmes.Supporting subsistence agriculturalactivities can help ensure foodsecurity and nutrition, generatingincome for the extreme rural poor,and providing them with accessto basic staples and higher-valuefoods. Policy tools to promote foodsecurity include asset transfers,such as small animals and livestock,building fish ponds, and home andschool gardens. Social protection,particularly nutrition-sensitive socialprotection, which includes regularcash transfers, reinforces linkages toxi

ENDING EXTREME POVERTY IN RURAL AREASnatural resources, such as landlessworkers and “livestock-less” herders.These gaps highlight the need tobetter articulate agricultural, food andenvironmental policies with povertyeradication, inequality reduction anddecent work promotion strategies.nutrition education, health services,and school food programmes,particularly in marginal areas.Adopting the Right to Food canhelp guarantee the implementationof these fundamental policies.Agriculture not only plays a keyrole in the transformation of theeconomy, but it is also crucialin ending extreme poverty.In developing countries, growth inagriculture has been more povertyreducing than growth in othersectors, having bigger impacts on therural extreme poor, in the poorestcountries. However, agriculture isoften not well-embedded in povertyeradication strategies or given theprominence that it deserves. The leadmandate to deal with poverty issuesat country level is often given tothe ministries of social affairs ratherthan the ministries of agricultureor the environment. As a result,agricultural policies tend to neglectthe extreme poor, especially thosewho do not have access to productiveEnding extreme poverty andhunger in rural areas will requiregenerating decent employment,both in the agricultural andnon-agricultural sectors, throughsustainable agricultural and ruraltransformation. While agriculture isthe main source of food and incomefor the rural extreme poor, promotingtheir participation in off-farmactivities, such as food transformation,processing and packaging, particularlyin more favourable rural areas,is crucial for diversifying theirlivelihoods. Activities outside thefood system, such as environmentalservices in remote areas, can beparticularly beneficial for thosewith fewer resources, includingthe landless, women and youth.xii

Natural resources and ecosystemservices are the basis for sustainableand productive food andagricultural systems. Many of theextreme poor in rural areas dependon access to water, forests, fisheries,and land to sustain their agriculturallivelihoods. Climate change, landdegradation, pollution, and thedepletion of natural resources andbiodiversity are amongst the majorimpediments to the sustainability oflivelihoods of indigenous peoples,pastoralists, forest people, and fisherfolks – who also tend to be the poorestand most marginalized communitiesin society. Targeted policy actions cansupport livelihoods by enhancinglocal knowledge, introducing newtechniques for the sustainablemanagement of resources, promotingclimate-smart and organic agriculture,and sustaining vital ecosystem services.conflicts, weather events, pestsand diseases, particularly in ‘earlywarning and early action systems’can lead to the formulation ofearly adequate responses, preventrisks from developing into crises,and reduce the cost of response.Social protection contributes toincreasing the resilience of the extremepoor, helping them to effectivelycope with the negative impacts ofclimate change and natural disasters.Finally, humanitarian programmescan also help restore the necessaryconditions for agricultural livelihoods.Reaching the extreme poor willrequire more focused actionsin addition to broad-basedinterventions. The eradication ofextreme poverty is possible with theright investments in the dedicatedpolicies and programmes that reachthe extreme rural poor directly, andwith a deeper understanding of thechallenges the rural poor face incomparison with the moderate poorand the rest of the population.Integrating conflict-sensitiveanalysis and assessments of therural extreme poor’s specificvulnerabilities to disaster-relatedxiii

ENDING EXTREME POVERTY IN RURAL AREASxiv

1IntroductionSustainable Development Goal(SDG) 1, Ending poverty in allits forms, everywhere, is one ofthe most ambitious goals setby the 2030 Agenda for SustainableDevelopment. Target 1.1 of SDG 1focuses specifically on Eradicatingextreme poverty in the next 12 years.development. Progress towards endingextreme poverty is largely related tothe way societies are structured andthe way resources are distributed.While these structures will continueto play a determining indirect role,reaching the extreme poor will requiremore focused actions in additionto broad-based interventions.This includes understanding thespecific challenges that the extremepoor face compared to the moderatepoor and the rest of the population, aswell as investing in and expanding thededicated policies and programmesthat reach them directly. Actions aimedat ending extreme poverty will alsoneed to recognize their social andeconomic endowment and potential.While considerable progress has beenmade over the last three decades inreducing extreme poverty and povertyoverall, about 736 million people1 –10 percent of the global population– still live in extreme poverty (WorldBank, 2018a), and most of them residein rural areas. The pace of povertyreduction may slow as those who are“left behind”face greater vulnerabilitiesand structural constraints, whichprevent them from benefitingfrom overall economic growth andThe report focuses on the rural extremepoor, who constitute about 80 percent1 The report uses the World Bank measure for most figures. The measure is based on consumption data(in this case, from 2015) and a poverty line of USD 1.90 a day in 2011 PPP – purchasing power parity.Data is from Povcalnet (World Bank), a global database that covers about 89 percent of the total globalpopulation. In the other sections, the report uses other measures of poverty, including multidimensionalpoverty and chronic poverty. Consistency across the report is difficult given the different sources ofdata on poverty, particularly on rural poverty. The bottom line is focusing action on the poorest of thepoor, given the best data available, and considering the multiple dimensions and cycles of poverty.1

ENDING EXTREME POVERTY IN RURAL AREASrural areas, and decreasing income andnon-income inequality. Together withTarget 2.1 of the SDGs, on endinghunger, the extent to which thesegoals are reached will determine thesuccess of the whole 2030 agenda.of the extreme poor globally (Castañedaet al., 2018). This population is nothomogeneous: the extreme poorexperience very diverse situationsof social and economic exclusion,including discrimination, isolation andpolitical disempowerment. What theyoften have in common is their highdependence on natural resourcesand agriculture for their livelihoods.Most of the extreme poor alsoengage in multiple non-agriculturalactivities to diversify their sourcesof income. While the report focuseson the extreme poor living in ruralareas, it also recognizes the linkagesbetween rural areas and small townsand cities, and their importance forgenerating sustainable livelihoods andinclusion for the rural extreme poor.This document presents an analysisof the challenges that countries facein their efforts to eradicate extremepoverty by 2030. There are six sectionsin the document, which focus on ruralareas: section 1 introduces SDG1,Target 1.1, and the need to eradicatepoverty; section 2 presents the extentof the challenge; section 3 profiles thecharacteristics of the rural extremepoor; section 4 analyses the prospectsof reaching Target 1.1 in rural areas,considering obstacles to progress;section 5 highlights some countryexperiences and lessons in eradicatingextreme poverty; and section 6 exploresthe role of agriculture, food systemsand natural resources in sustaininglivelihoods, eradicating extreme povertyand reducing rural poverty, highlightingthe policies needed to better reachthe extreme poor in rural areas.Going the extra mile to reach the ruralextreme poor and addressing theirneeds is not only a crucial factor inthe success of SDG1, but it will alsogenerate positive outcomes on manyfronts, including helping to preventcrises and conflict, making populationsmore resilient to climatic shocks,providing economic alternatives in2

2Understanding theextent of the challengein rural areasThe extent of the challengeof eradicating extremepoverty is set by Target1.1 of the SDGs. Target 1.1is currently measured by indicator1.1.1: Proportion of population belowthe international poverty line, bysex, age, employment status andgeographical location (urban/rural).Indicator 1.1.1 defines the extremepoor as those individuals earningless than USD 1.25 a day – theinternational extreme poverty lineset at the time the indicator wasapproved by UNSD (2018), whichis monitored by the World Bank.2Using this measure, there are about736 million people, representing10 percent of the global population,still living in extreme poverty.While income is a good measure tounderstand who the extreme poor are,it only captures the income dimensionof extreme poverty. In addition toincome, extreme poverty is alsomanifested by social marginalizationand exclusion, different manifestationsof malnutrition, poor living conditions,lack of access to basic services, resourcesand employment opportunities, amongothers. To gain a better understandingpoverty, several measures are used,to the extent these are available3,2 The official indicator is likely to be updated to USD 1.90 a day. Povcalnet was last updated inSeptember 2018 and the World Bank numbers currently cover 164 countries, covering 65 percentof the world’s population. The USD 1.9 a day line corresponds to the average poverty line set bythe average of official poverty lines for a group of least developed countries. The multidimensionalpoverty index has also been proposed and has been included by several countries in their SDGsVoluntary National Reviews.3 The two measures of poverty described in this section should be seen as complementary, as they aremeasuring different aspects of poverty. Together, they help to better understand the phenomenon ofpoverty, while at the same time, point to specific policy actions.3

ENDING EXTREME POVERTY IN RURAL AREASassesses poverty at the individuallevel: it complements traditionalincome-based poverty measures bycapturing the severe deprivationsfaced by individuals in terms of health,education, and living standards (OPHI,2018)6. Based on this index, if someoneis deprived in a third or more of ten(weighted) indicators, the globalindex identifies them as “MPI poor”,and the extent – or intensity – of theirpoverty is measured by the number ofdeprivations they are experiencing.respecting countries contexts andtheir options of measurement.Multidimensional poverty measuresare good complements of incomeand consumption-based povertymeasures, as they provide deeperinsight into the degrees of deprivationand vulnerability of the extreme poor.4One of the

many challenges that lie ahead? By gaining a deeper understanding of poverty, and the characteristics of the extreme rural poor in particular, the right policies can be put in place to reach those most in need. This report presents the contribution that agriculture, food systems and the sustainable use of natural resources can make to securing the