Transcription

Lawati et al. BMC Family Practice (2018) EARCH ARTICLEOpen AccessPatient safety and safety culture in primaryhealth care: a systematic reviewMuna Habib AL. Lawati1,2* , Sarah Dennis3,4, Stephanie D. Short1 and Nadia Noor Abdulhadi5AbstractBackground: Patient safety in primary care is an emerging field of research with a growing evidence base inwestern countries but little has been explored in the Gulf Cooperation Council Countries (GCC) including theSultanate of Oman. This study aimed to review the literature on the safety culture and patient safety measures usedglobally to inform the development of safety culture among health care workers in primary care with a particularfocus on the Middle East.Methods: A systematic review of the literature. Searches were undertaken using Medline, EMBASE, CINAHL andScopus from the year 2000 to 2014. Terms defining safety culture were combined with terms identifying patientsafety and primary care.Results: The database searches identified 3072 papers that were screened for inclusion in the review. After the screeningand verification, data were extracted from 28 papers that described safety culture in primary care. The global distributionof the articles is as follows: the Netherlands (7), the United States (5), Germany (4), the United Kingdom (1), Australia,Canada and Brazil (two for each country), and with one each from Turkey, Iran, Saudi Arabia and Kuwait. Thecharacteristics of the included studies were grouped under the following themes: safety culture in primary care, incidentreporting, safety climate and adverse events. The most common theme from 2011 onwards was the assessment of safetyculture in primary care (13 studies, 46%). The most commonly used safety culture assessment tool is the Hospital surveyon patient safety culture (HSOPSC) which has been used in developing countries in the Middle East.Conclusions: This systematic review reveals that the most important first step is the assessment of safety culture inprimary care which will provide a basic understanding to safety-related perceptions of health care providers. The HSOPSChas been commonly used in Kuwait, Turkey, and Iran.Keywords: Patent safety, Safety culture, Primary care, Gulf countries, OmanBackgroundThe World Health Organization (WHO) defines patientsafety as “the prevention of errors and adverse effects topatients associated with health care” and “to do no harmto patients” [1, 2]. There are millions of patients globallywho suffer disabilities, injuries or death each year due tounsafe medical practices [3]. This has led to the widerrecognition of the importance of patient safety, the incorporation of patient safety approaches into the strategic plans of health care organizations and a growing* Correspondence: drmunali@gmail.com1Faculty of Health Sciences, Discipline of Behavioral and Social Sciences inHealth, The University of Sydney, Science Road, Sydney, NSW 2006, Australia2Department of Quality Assurance and Patient Safety, Ministry of Health,P.O.Box, 626, Wadi Al Kabir, 117 Muscat, PC, OmanFull list of author information is available at the end of the articlebody of research in this field [4]. “To Err is Human:Building a Safer Health System” was published in 1999by the Institute of Medicine (IOM), it emphasized thatsafety was the key fundamental concern. This was alandmark publication for patient safety and warned oferrors in health care and the potential for patient harm[5]. Patient safety in primary care has not been exploredto the same extent as in the hospital settings [6] howevermore recently there has been more research emerging inprimary care [7–10]. Achieving a culture of safety requires an understanding of the values, attitudes, beliefsand norms that are important to health care organizationand what attitudes and behaviors are appropriate and expected for patient safety [10]. The Author(s). 2018 Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, andreproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link tothe Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication o/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Lawati et al. BMC Family Practice (2018) 19:104This systematic review aimed to identify the patientsafety measures used globally to assess the effectivenessof safety culture in primary care. The outcome of thisstudy will help to inform strategies for patient safety forprimary care in Oman in order to accomplish the 2050 vision. The specific research questions for this review were:1. What processes or systems are in place to facilitatea safety culture in in primary care?2. What are the measures used globally to assess theeffectiveness of safety culture in primary care?3. What is the impact of safety culture in primary care?MethodsA systematic review of the published literature from2000 to 2014 was conducted. This date range was chosenbecause it followed the publication of “To Err is Human”in 1999 [5]. The databases used to identify the articles wereMedline, Embase, CINAHL and Scopus. The terms used inMedline search were Health System, Safety Culture, PatientSafety, Primary Health care, Adverse Event, Health CareProfessionals and Health Care Managers.There were several key definitions used to scope thereview and inform the inclusion and exclusion criteria:1. Patient Safety: WHO defines patient safety “as theabsence of preventable harm to a patient during theprocess of health care” [1].2. Safety Culture: Defined “as shared values, attitudes,perceptions, competencies and patterns of behaviors”.3. Primary Care: WHO defined primary care “associally appropriate, universally accessible,scientifically sound first level care provided by asuitably trained workforce supported by integratedreferral systems (to secondary care or tertiary care)and in a way that gives priority to those most needed,maximizes community and individual self-relianceand participation and involves collaboration withother sectors. It includes the following: healthpromotion, illness prevention, care of the sick,advocacy and community development” [11].Articles were included in the review if they were published in the year 2000 or later and met the followingfour inclusion criteria:Page 2 of 123. They discussed patient safety in primary care, orsafety culture in primary care.4. Published in English.Articles were excluded if they were opinion papers/essays, editorial reviews, interviews, comments or narrativereviews.After removal of the duplicates and papers with no abstracts, the titles and abstracts of 61 papers werescreened by two researchers (MA and NN). The full textof all articles remaining were obtained and reviewed by tworesearchers (MA and NN). The full text articles were readand those that met the inclusion criteria were included inthe review. The flow chart in Additional file 1 illustrates theselection process by using Preferred Reporting Itemsfor Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA)flowchart [12].The following information was extracted from the included articles: authors, year of publication, title andaims, objectives, methods, country and key findings. Toassess the quality three different tools were used accordingto study design. Systematic reviews were evaluated byAssessing Methodological Quality of Systematic Review(AMSTAR), quantitative studies were assessed by EffectivePublic Health Practice Project (EPHPP) and cross sectional studies were evaluated by using Strengthening theReporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology(STROBE) [13].ResultsThe database searches identified 3072 papers that werescreened for inclusion in the review. After title and abstractscreening there were 61 remaining papers that described interventions in safety culture in primary care. Following verification and data extraction there were a total number of 28articles included in the systematic review (Additional file 1).The global distribution of the articles are as follows: theNetherlands (7), the United States (5), Germany (4),Australia, Canada and Brazil (two for each country), theUnited Kingdom (1), and with one each from Turkey, Iran,Saudi Arabia and Kuwait. The characteristics of the included studies grouped under the following themes: safetyculture in primary care, incident reporting, safety climateand adverse events are specified in Table 1.Safety culture in primary care1. They reported on the use of patient safety tools orapproaches or mechanisms or procedures used inprimary health care with an impact on patient care(outcome) measured.2. If they were contained any of the followingmethodologies; systematic review, interventionstudy (randomized controlled trials), descriptivestudy or qualitative design.Thirteen studies addressed safety culture and tools to assess safety culture in general practice and most (9/13)were cross sectional studies [7, 8, 10, 14–19], the otherstudies were qualitative interviews [20], a systematic review [21], a retrospective audit [22], randomized controltrial [22], mixed methods [23] and a case study [24].The definition of patient safety culture varied amongthe articles. A common definition of safety culture was

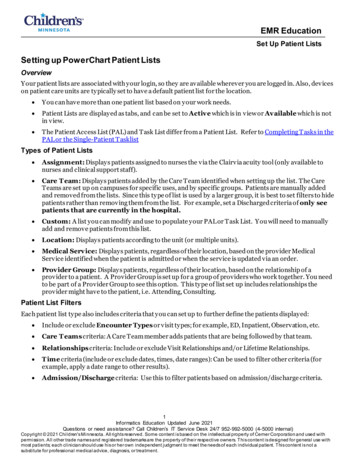

Lawati et al. BMC Family Practice (2018) 19:104Page 3 of 12Table 1 Characteristics of the selected studies in the systematic review (studies categorized by themes)Author and yearTitleStudy designStudy Results and significantconclusionsQuality assessmentsSafety Culture in primary care settingKirk S [26] 2007Patient safety culture inprimary care; developing atheoretical framework forpractical use.Literature reviewfollowed by semistructured interviews.Study details development ofthe Manchester Patient SafetyFrameworkBodur S [8] 2009A survey on patient safety inprimary healthcare servicesin TurkeyCross sectional studyHospital survey on patient safetysurvey was adapted withmodification to fit the Turkishprimary care context. Positiveresponses were highest forteamwork within the units (76%)and lowest for events reporting(59%) and non-punitive responseto errors (18%). Health centeradministrator must focus onimproving patient safety cultureand encourage staff to reporterrors without fear.All items of STROBEstatement coveredDorien LM Zwart[22] 2011Patient safety culturemeasurement in generalpractice. Clinimetricproperties of ‘SCOPE’Descriptive Crosssectional study88.8% completed thequestionnaire, out of which25% were GPs, 60% medicaladministrative assistants and 15%nurses. SCOPE seems a suitabletool to measure safety culture ingeneral practiceAll items of STROBEstatement coveredNargis T [7] 2012The first study of patientsafety culture in the Iranianprimary health care.Cross sectional studyTeamwork across the units scoredthe highest 77.7%, continuousorganization learning scored 72%and the lowest was non-punitiveresponse to error 17%.All items of STROBEstatement coveredJacobs L [27] 2012Creating a culture of patientsafety in primary carephysicians group.Proactive approach CasestudyStudy based on adaptation ofmedical risk managementstrategy to help create a cultureof safety in primary care. This ledto reduction of malpractice claimsand enhanced learningexperience among physicians.All items of STROBEstatement coveredBenjamin H [20]2012Better medical office safetyculture is not associatedwith better scores on qualitymeasures.Cross section studyResponse rate was 79%,significate variations on safetyculture scores and quality scores.There was no associationbetween safety culture andquality outcome measures.All items of STROBEstatement coveredYahia M [21] 2013Attitude of primary carephysicians toward safety inAseer region, Saudi ArabiaCross sectional studyHighest score was given toreduction of medical errors (6.2points). Followed by training andlearning on patient safety (6 and5.9). Undergraduate training wasgiven the least score andparticipants did not agree thaterrors were due to nurses ordoctor’s carelessness.All items of STROBEstatement coveredLucine M [29]2013Is health professional’sperception of patient safetyrelated to figures on safetyincidents?RetrospectiveObservational studyCommunication breakdowninside or outside the practice arethreats to patient safety. Thestudy indicates that assessmentsof professional’s perception arecomplementary to observedsafety incidents.All items of STROBEstatement covered

Lawati et al. BMC Family Practice (2018) 19:104Page 4 of 12Table 1 Characteristics of the selected studies in the systematic review (studies categorized by themes) (Continued)Author and yearTitleStudy designStudy Results and significantconclusionsQuality assessmentsFernando P [18]2013Patient safety culture inprimary health care.Cross sectional studyWorking conditions, teamworkclimate, communication andmanagement of healthcare weresignificate with patient safety culture.All items of STROBEstatement coveredMaha G [10] 2014Assessment of patient safetyculture in primary healthcare setting in Kuwait.Cross sectional studiesHospital survey on patient safetysurvey was adapted withmodification to fit the Kuwaitiprimary care context. Dimensionswith low positivity were: thenon-punitive response to errors,frequency to error reporting,staffing, communication opennessand center handoffs. High positivitywas teamwork within the unit andorganizational learning. Overall thesafety culture is not strong in Kuwait.All items of STROBEstatement coveredNatasha J [24]2014Improving patient safety inprimary care: a systematicreview.Systematic review2 articles selected which providebasic understanding of improvementstrategies in primary care, low levelof evidence9/11 using AMSTARHoffmann B [25]2014Effects of a team basedassessment and interventionon patient safety culture ingeneral practice: an openrandomized controlled trail.Randomized control trailFraTrix, which was derived fromMaPSaf, was applied over aperiod of 9 months in theintervention practice. Fratrix didn’tlead to measurable improvementsin error managements but lead tobetter reporting of patient safetyincidents.(EPHPP Statementused forassessment)A strong studywhich highlightedlimitations andimplications.Palacios D [23]2010Dimensions of patient safetyculture in family practice.Qualitative case studyExplores the dimensions of patientsafety culture related to familypractice in UK, USA and Canada.Global rating of thispaper wasmoderate (EffectivePublic HealthPractice Project)Incident reporting in primary care settingDouglas H [35]2004Event reporting to a primarycare patient safety reportingsystem: A report from theASIPS collaborative.Incident report analysisHighest number of events wasreported due to communicationerrors 71% followed by diagnosticand medication errors. A safereporting system, which relies onvoluntary reporting, can beadapted in primary care settings.All items of STROBEstatement coveredSingh R [34] 2006“Chance favors only theprepared mind”. Preparingminds to systematicallyreduce hazards in thetesting process in primarycare.Prospective studyA proposed approach called assystematic appraisal of risk and itsmanagement for error reductionfor test process (SARAIMER) wasused. Successfully used inmedication safety in primary care.All items of STROBEstatement coveredMakeham M [33]2007Patient safety eventsreported in general practice:taxonomy.TaxonomyThe outline taxonomy of eventsin general practice provides acomplete tool for cliniciansdescribing threats to patientsafety and can build an errorreporting system.All items of STROBEstatement coveredMarleen S [38]2010Patient safety in out-ofhour’s primary care: a reviewof patient records.RetrospectiveMost frequent incidents occur inout-of- hours primary care wereincidents on treatment (56%).Incidents did not result in patientharm. Improved understanding inclinical reason and adherence toguidelines will enhance patient safety.All items of STROBEstatement covered

Lawati et al. BMC Family Practice (2018) 19:104Page 5 of 12Table 1 Characteristics of the selected studies in the systematic review (studies categorized by themes) (Continued)Author and yearTitleStudy designStudy Results and significantconclusionsQuality assessmentsZwart D [6] 2011Central or local incidentreporting? A comparativestudy in Dutch GP out ofhour’s services.Quasi experimental studyLocal incident reporting facilitatesthe willingness to report and fasterimplementation of improvements.In contrast, central reporting seemsbetter at addressing generic andrecurring safety issues. Bothapproaches should be combined.All items of STROBEstatement coveredDorien LM Zwart[37] 2011Feasibility of center-basedincident reporting in primaryhealthcare: The SPIEGEL studyProspectiveObservational study476 incidents reported in9 months, 62% incidents reportedin the reporting week and majoritywere process oriented. All involvedcenters initiated improvementstrategies due to reportedincidents. Locally implementedincident reporting procedure as atool for managing patient safety isfeasible in general practice.All items of STROBEstatement coveredZwart D [36] 2013Introducing incidentreporting in primary care: atranslation from safetyscience into medical practiceProspectiveObservational studyThe aim of the study was tounderstand and describeparticular ways primary carephysicians make incidentreporting procedure part ofdealing with safety issues.All items of STROBEstatement coveredMarchon SG [39]2014Patient safety in primaryhealth care: a systematicreview.Systematic review33 articles were selected from2007 to 2012: 26% onretrospective studies, 44%prospective studies. Frequentmethod used was incidentreporting system 45% and themost relevant contributing factorwas communication failure.8/11 using AMSTARSafety climate in primary care settingHoffmann B [35]2011The Frankfurt patient safetyclimate questionnaire forgeneral practice (FraSik):analysis of psychometricproperties.Cross sectional studiesQuestionnaire was modified inorder to be applicable for generalpractice. The tool can be used forassessment of the safety climateof general practice.All items of STROBEstatement coveredDe Wet C [37]2012Measuring perception ofsafety climate in primarycare: a cross- sectionalstudy.Cross sectional studyPerception of safety climate in theUK primary care with a validatedtool specifically designed for it.Measuring safety climate hasvarious benefits at the individual,practice and regional level.All items of STROBEstatement coveredHoffmann B [36]2013Impact of individual andteam features of patientsafety climate: A survey infamily practice.Cross section studiesFraSik was used to identifypotential predictors of the safetyclimate in family practice inGermany. The overall climate waspositive but the healthprofessional’s use of incidentreporting and systems approachto errors was fairly rare.All items of STROBEstatement coveredModified Delphi process.114 software features weredeveloped which relate torecording and use of patient data,the medication selection process,prescribing decision-makingsupport, monitoring drug therapyand clinical reports. This featuresupports safety and quality of prescription of medication in generalpractice.Modified Delphiprocess.Adverse events in primary care settingSweidan M [41]2010Identification of features ofelectronic prescribing systemsto support quality and safetyin primary care using amodified Delphi process.

Lawati et al. BMC Family Practice (2018) 19:104Page 6 of 12Table 1 Characteristics of the selected studies in the systematic review (studies categorized by themes) (Continued)Author and yearTitleStudy designStudy Results and significantconclusionsQuality assessmentsWong K [40] 2010A systematic review ofmedication safety outcomesrelated to drug interactionsoftware.Systematic reviewNo study addressed the benefitsand harms or cost effectiveness ofdrug interactions. The evidencedoes not support a benefit ofsoftware on medication safety orsupport any practice in this policy.7/11 using AMSTARSingh R [42] 2004Estimation impacts on safetycaused by the introductionof the electronic medicalrecords in primary care.FMEAHazard score was calculated foreach error before and 1 year afterimplementation of electronicmedical records. Hazardsperceived by staffs decreased indomains of physician –nurses andphysicians –chart. But increase inphysician- patient and nursechart domain.All items of STROBEstatement coveredJoachim S [43]2011Effectiveness of a qualityimprovement program inimproving management ofprimary care practicesCross sectional studyPrimary care practices thatcompleted the European Practiceassessments twice over a period of3 yrs showed overall improvementsin practice management, qualityand safety and complaintmanagement.All items of STROBEstatement coveredutilized in eight studies, which referred to shared values,perceptions, attitudes, competencies and behaviorswithin an organization [8, 10, 14, 15, 19–23]. The definition of safety culture was lacking in two articles butthey defined patient safety and patient safety incidentsrespectively [18]. There was one study where patientsafety culture was defined as acceptance and actions of patient safety as the first priority in the organization [7] andfour articles did not define safety culture [17, 24–26].Two studies of safety culture utilized a qualitative approach, followed by a survey or an audit. The othereleven studies utililized quantitative tools to assess safetyculture. The systematic review included a study by Gaalet al. in the Netherlands that explored the views of primary care doctors and nurses to identify aspects of carelinked to patient safety in a qualitative study [16]. Medication safety was most frequently mentioned with incidents occurring in diagnosis and treatment, errors incommunication and poor patient doctor relationshipwere the most common errors in primary care [25]. Theaspects that were considered essential for patient safetywere; the availability of medical instruments, telephoneaccessibility and safe electric sockets. General practitioners relied on the skills and knowledge of the practicenurses since most of the patients were seen by them.The GPs did not supervise the practice nurses whenproviding advice to patients over the phone which theyfelt was a threat to patient safety. The results of thisqualitative study were used to develop a web-based survey, which was one of the first to assess the views ofgeneral practitioners (GPs) on patient safety [16] in theNetherlands. They found that GPs were concerned aboutthe maintenance of medical records, prescription andmonitoring of medication.Another Dutch study identified that health care professionals who had a perception and understanding of patient safety had more incidents recorded [26]. All thehealth professionals surveyed felt that communicationbreakdown inside and outside the practice was a threat topatient safety and was associated with more incidents [26].A systematic review on the use of interventions of patient safety that affect safety culture in primary care onlyincluded two studies [21]. One of the included studiesdescribed the implementation of an electronic medicalrecords system in general practice using the safety attribute questionnaire as a part of patient safety improvements [21]. The authors facilitated two workshops forgeneral practice on risk management and significantaudit analysis. The authors concluded that further research was required to assess the effect of interventionson safety culture in primary care [21].Two main tools were used to measure safety culture;the Manchester Patient Safety Framework (MaPSaF) andthe Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture (HSOPSC).The Manchester Patient Safety Framework (MaPSaF) [23]was developed to measure the multidimensional and dynamic nature of safety culture and enabled recognition ofsubcultures within a single organization because subcultures act as a powerful influence on error detection andlearning. In addition, the tool provided insights into patient safety culture, facilitated interactive self-reflectionabout safety culture of an organization, explored differences in perception among different staff categories,helped understand how mature an organization was in

Lawati et al. BMC Family Practice (2018) 19:104terms of safety culture and evaluated interventions whichwere aimed at improving safety culture. The MaPSaF isfounded on Westrum’s typology of organizational communication from 1992, which defined how different typesof organizations process information. This typology wasexpanded upon by Parker and Hudson to describe fivelevels of progressively maturing organizational safety culture. The MaPSaF measures ten dimensions of safety culture, derived from a literature review on patient safety inprimary care and in-depth interviews and focus group discussions with health care professionals and managers. Thedimensions are commitment to overall safety, prioritygiven to safety; system errors and individual responsibility;recording incidents and best practice; evaluation incidentsand best practice; learning and effecting change; communication about safety issues; staff education and trainingand team work approach. The tool helped to acknowledgethat patient safety was multidimensional and complex, offered insights and demonstrated strengths and weaknessesof a patient safety culture, provided differences in perception among and helped the organization to understandwhat a mature safety culture in health care might looklike. It should not be used to conduct performance management nor to divide or attribute blame when the organization’s safety culture is not sufficiently mature [27]. Thistool is best used as a facilitative educational tool for healthcare providers and managers.The Manchester Patient Safety Framework (MaPSaF)[14, 22] has been adapted for use in different health systems. The MaPSaF was modified and tested in the NewZealand context to facilitate learning about safety cultureand facilitate team communication mentioned in thesystematic review [15]. The MaPSaF has been modifiedfor use in the German health system and was renamedthe Frankfurt Patient Safety Matrix (FraTix) [22]. Thistool was validated and used in a randomized control trialof 60 general practices to determine safety culture at different levels. There were no differences between thegeneral practice physicians’ groups but the interventiongroup showed improved reporting and management ofpatient safety incidents than the control group. FraTixappeared to be a good tool for self-assessments aimed atimproving safety culture but did not lead to measurableimprovements in error management.The Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture(HSOPSC) was developed by the Agency of Health Careand Research for Hospitals in 2004, and has beenadapted and modified for other health care settings. Itmeasures healthcare professional’s perspectives towardssafety culture at the individual, unit and organizationallevel. It was pilot tested with more than 1400 hospitalemployees from 21 hospitals across the USA [28]. Thetool was developed after an extensive literature reviewon safety, accidents, medical errors, safety climate andPage 7 of 12culture and organizational climate and culture. Therewere also interviews with hospital staff and surveys. Theinstrument includes fourteen dimensions, twelve aremultiple item dimensions (two safety culture dimensionsand two outcome dimensions) and the last two are single item dimensions used to check the validity. This toolhas a broad spectrum of applicability has been completed by all types of hospital staff from security guardsto nurses, paramedical staff and physicians employed bythe organization. In terms of reliability and validity theHSOPSC was found to be “psychometrically sound atthe individual, unit and hospital level analysis” [29] inprimary care settings. It has since been used in Kuwait,Turkey, the Netherlands and Iran [7, 8, 10, 19]. The dimension most commonly scored among Kuwait, Turkeyand Iran was teamwork within the units and the leastwas non-punitive response to errors. Similarly, theHSOPSC has since been adapted and validated for usein Dutch general practice, and was renamed SCOPE[19], a Dutch abbreviation for systematic culture on patient safety in primary care. Table 2 compares the characteristics of the MaPSaF and HSOPSC.Paese [15] used the Safety Attitudes Questionnaire(SAQ) to assess attitudes to safety culture in Brazilianprimary care. The survey was conducted among community health agents, nursing technicians and nurses.The SAQ assesses the quality of safety and teamworkstandards in a given time in a health care organization.Nine attributes are assessed which are: job satisfaction,teamwork climate, perception of work environment,communication, patient safety, ongoing education, management of the healthcare center, recognition of stress,error prevention by using preventive measures. Patientsafety attribute was considered to be an important attribute among the respondents whereas prevention measures to avoid errors were viewed as being a lessimportant attribute.A case study in a primary care physician practice inthe USA explored the impact of a comprehensive riskmanagement program from 2003 to 2009. The programresulted in fewer insurance claims and considerable costsavings thereby enhancing patient safety culture inprimary care by implementing risk management program, the program further provided the physicians’ asense of control over the treatment of malpractice andencouraged them to provide the best care for theirpatients [24].Incident reporting in primary careIncident reporting to assess patient safety in primarycare has grown in importance. There were two types ofstudy under t

body of research in this field [4]. "To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System" was published in 1999 by the Institute of Medicine (IOM), it emphasized that safety was the key fundamental concern. This was a landmark publication for patient safety and warned of errors in health care and the potential for patient harm [5].