Transcription

Ancient Jewish Philosophy asExpressed in TanakhFrom an independent Bible study classFrank A. Nemec, Jr.Course Syllabus and NotesDecember 5, 2021

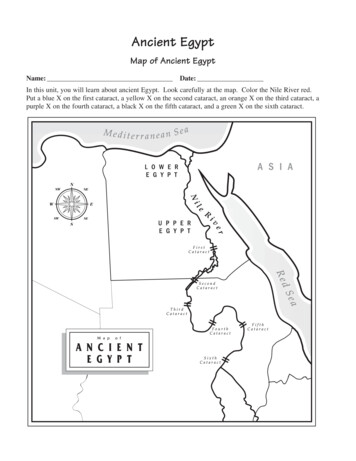

Ancient Jewish Philosophy as Expressed in TanakhFrank A. Nemec, Jr.Table of ContentsGeneral Guiding Questions.6Why These Texts were Written.8Documentary Hypothesis.9Jahwist source.13Elohist source.13Deuteronomist source.14Priestly source.14Literary Genres.14Narrative.14History.14Legend and Myth.15Allegory.15Biblical Hebrew Poetry.15History vs. Doctrine.16Folklore Analysis and Type Scenes.16Names of God.17Greek Mythology.19Estimated Timeline.19The Covenants.20Key Bible Texts on the Covenants.21The Mosaic Covenant.23The Books of Tanakh.23Genesis.23The Divine Council.24In Our Image.24Environmental Stewardship.25Melchizedek.32The Sacrifice of Isaac.34Exodus.41Unification of Elohim and Yahweh.45Population of Ancient Israel.49Consecration of the Firstborn.49Moses – A First Appraisal.52Shekel.58The Ethnic Cleansing of the Conquest.62Exodus Review.63Ancient Jewish Philosophy as Expressed in Tanakh, by Frank Nemec, page 2

Leviticus.63Questions to Guide Your Study.63Microcosm of Ancient Jewish Philosophy.66Numbers.71Statistical Abstract of Numbers 3.73Pillar of Cloud and Appearance of Fire.74The Spirit.75Bearing Their Iniquity.77Deuteronomy.81Preamble and Historical Prologue.81Deuteronomic Legal Code.82The Ten Commandments and the Morality of Ancient Israel.82Safe Deposit and Public Readings.83Witnesses.83Blessings and Curses.83Golden Calf.86Jerusalem.87Son of God.88Review.91Joshua.91Judges.97Angel of the LORD.98Review.103Ruth.1031 Samuel.104Harmony of h.122Wisdom Literature.122Prophetic and Apocalyptic Literature.122Isaiah.124Second Temple Judaism.124New Testament.124James.124Paul.124Deutero-Pauline Epistles.124Pastoral on.125Resources.126Parallels between Exodus and Numbers.126References.127Ancient Jewish Philosophy as Expressed in Tanakh, by Frank Nemec, page 3

Ancient Jewish Philosophy as Expressed in Tanakh, by Frank Nemec, page 4

General MaterialThis document is evolving to capture an understanding of philosophical thought of ancient Israel, asthose thoughts are expressed in Tanakh (what Christians renamed as the Old Testament). These notesbegan as a framework for a class on the history of Israel as recorded in the Bible, and in the context ofits peers, and as matched with history. The class met Sunday evenings 6:30-8pm in room 3191 at ValleyChurch, Cupertino, California, starting June 10, 2012, then later using Google Meet as personalschedules permit. The reading itself is to be done by each student, outside of class, preferably inadvance of the discussion. It's not primarily a doctrine class. Experiencing the overview requires adisciplined style of reading. It's tempting to read footnotes and follow cross references. Don'tprocrastinate on the reading, especially in the beginning. The discipline to just read the Bible is difficult.Page counts are of the paper ESV Bible. They include the introductions, illustrations, and footnotes.The total is about 600 pages.This document includes some material on the New Testament, the collection of texts chosen torepresent the canon of orthodox Christianity. Most of Paul will be a separate document.I encourage taking notes to bring to class. Thoughts and answers should be based on the texts up to thatpoint. That is, don't rewrite the texts to incorporate later ideas. Input from extra-biblical sources is verywelcome, and very much helps understand biblical texts.The latest version of these notes is always available on the web page for this ryofIsrael/DisclaimersI accepted the role of leader or facilitator of this class by request of the people attending this Sundayevening Bible study. I intend to encourage attention to certain questions and issues, as can be seen bythe rest of this syllabus. I intend to offer some of my ideas on these and related subjects. I do not speakas a teacher or other official of Valley Church. The ideas are mine, not those of Valley Church, itselders, pastors, or staff. This is not an official Discipleship Elective of Valley Church.The first item in the doctrinal statement of Valley Church reads, “We believe in the Scriptures of theOld and New Testaments as being inspired by God and completely inerrant in the original writings andof supreme and final authority in faith and life.” This encapsulates a Fundamentalist position. Mine isConservative, but not Fundamentalist. I discuss this in my notes on the gospels. I neither insist norexpect that people agree with me on this or any other opinion I have or express.When I express a view about biblical scholarship in class, unless I say otherwise, it is generally aconsensus or a broadly held view among modern biblical textual scholars (not theologians), and ofscholars of the history and religions of the Ancient Near East. When I discuss ideas and theirdevelopment, the views are generally mine. That is, I present my understanding of the ideas each authorintended to communicate with his writing. I typically will not say whether or not I agree with thoseideas. That’s not the point of this study.I say so when I express an idea that is my own. But because of my memory problems, I may forget thatAncient Jewish Philosophy as Expressed in Tanakh, by Frank Nemec, page 5

I've read it somewhere. Significant ideas in my written notes are nearly always annotated with theirsource.The primary source for this class is the Bible texts themselves. The objective is to read them andunderstand them (exegesis), not to read into them (eisegesis).I admit some laziness or carelessness when I refer to things relating to Israel as Jewish. Hebrew orIsraeli might be more accurate in many cases. I will probably never get around to more careful andprecise use of these terms.HermeneuticI use the historical-critical hermeneutic as I study the texts of the Bible. I trace the ideas of the peopleof Israel as they develop over time, as reflected in their writings in Tanakh. Then, the ideas of NewTestament authors. People write to communicate their ideas. My objective is to understand and conveythose ideas, the ideas of the authors of the texts. This runs from pre-Israel (Abraham and his peers),ancient Israel, Israel under united monarchy, Exilic (Babylonian Diaspora), through post-Exilic (afterreturn to Israel under Cyrus). I consider ideas of Second Temple Judaism, especially around the firstcentury, as precursors to New Testament thought. I look at how these ideas appear in the sayings andteachings attributed to Jesus in the synoptic gospels. I look for these ideas in the writings of Paul.TranslationsIf you hold a doctrine of inspiration of the original autographs, then why would you settle for anythingless then an accurate translation of the best collection of texts that textual criticism can provide, basedon all manuscripts available today? Those are Masoretic and Nestles. Translations based on those texts,emphasizing formal equivalence ("essentially literal"), and faithful to the texts, are ESV, NRSV, andNASB. NET is almost as good. KJV, though a good translation into 17th century English, is ofsignificantly less value, since it's based on a different textual body (Textus Receptus). For the OldTestament, they used the 1524 Hebrew Rabbinic Bible, but chose Septuagint or Vulgate when theybetter suited their doctrines. That was definitely biased! The worst are the modern paraphrases whichwrite into modern language the interpretations of their authors. I read the Bible to understand what eachbiblical author meant, not what a ‘translator’ thinks they meant or wishes they meant.All of my quotations are from the ESV unless otherwise noted.Guiding Questions1. What kind of relationship do the people have with God? How does it change? In most Bibles,LORD is used for Yahweh, and God for Elohim. What do they call their God and theneighboring gods?2. What do God and the people expect from each other? What covenants are in play?3. How do the people govern themselves? What can you see about political and religiousleadership? How were leaders selected?4. How do the people relate to their neighbors?5. Where do ideas first appear? How are they different from earlier and later ideas, including ideasAncient Jewish Philosophy as Expressed in Tanakh, by Frank Nemec, page 6

of Christianity? How do the ideas differ from those of their neighbors? How do the ideas of thistext match the ideas of other biblical texts?6. By the modern definition, when does the history of Israel begin? You'll need to go well beyondthe text for that.Ancient Jewish Philosophy as Expressed in Tanakh, by Frank Nemec, page 7

Why These Texts were WrittenWhy were these texts (Torah and the rest of Tanakh) written? Perhaps this is the story. Under Saul andDavid, a dozen motley tribes were glued together to form a kingdom. It lasted for a few years, then splitin two, north and south. If you want to have a kingdom (in this case, a small empire), you need somecohesive factors to hold it together. We always treat 'us' more favorably than 'them', so how can we makepeople feel that they really are part of the greater whole, the same 'us'?First, tell them they are all related. Synthesize a legendary tradition of their common genealogy. Whileyou're at it, solidify their identity by crystallizing 'them'. Tell stories where the outsiders, though theymight be somewhat related to you, descend from less-than-honorable parentage. Go even further, andwrite legends saying you slaughtered most or all of them.Second, unify them under a common religion. Our (Israel, north) god is El. Your (Judah, south) god isYahweh. Your god told your leader (Moses) that he is really the same god as my god. So by definition,we all really worship the same god. Our practices are dictated by your leader, who said that thosepractices were dictated by your god, which is really also our god. We know all this because yourwritings say so.Third, unify them with a common literary heritage. Blend all their traditions into a unified narrative.But represent the traditions of each tribe enough that someone from a tribe will recognize his traditions.Of course, the blending will be biased toward the people who wrote it: the priestly and ruling class ofYahweh. The final editing of Torah reflects the 'reforms' of Josiah, shown most clearly in theDeuteronomistic texts. Because disparate traditions are blended, there will be contradictions. Stillvisible in trace form are practices we no longer practice, and beliefs we no longer believe. This is anearly example of what we now call revisionist history.At the peak of the united monarchy, David was king. David wanted what most monarchs want: for hischildren to rule in his place. So he got the priests to say that their god demanded that rule be limited tohis descendants. But he diluted the power of that declaration. With thousands of wives and concubinesbetween David and his son Solomon, it wasn't long before anyone in any of the tribes could claimDavidic descent. The father of my child was really Fred, but the child will get better treatment if I saythe father was the king. The price I pay is a night of pleasure with that strong, good-looking, powerfulking. Now we really don't know who the father is. Fred won't kill him because he thinks he's the father.The king won't kill him because he thinks he's the father. We have observed this behavior in animalpacks.Fourth, solidify the covenantal worldview, with the details and terms of their central philosophy, theMosaic Covenant. Judaism them became a ‘religion of the book’, perhaps the first. When ideas arewritten and preserved, it becomes much harder to change them. Christianity later followed suit with theformation of its canon. The editors convey the same message: We have the true and correct ideas, so wedon’t want anyone to change them, ever. If Judaism was correct in doing that, then Christianity waswrong.Ancient Jewish Philosophy as Expressed in Tanakh, by Frank Nemec, page 8

Finally, convey the etiology of Jewish philosophy. Google offers this (non-medical) definition, “theinvestigation or attribution of the cause or reason for something, often expressed in terms of historicalor mythical explanation.” Wikipedia expands, “An etiological myth, or origin myth, is a myth intendedto explain the origins of cult practices, natural phenomena, proper names and the like.” We see thispracticed extensively throughout Torah and all of Tanakh. Sometimes the name itself is the explanation.Course 653, The Old Testament, from The Teaching Company covers this in detail.Documentary HypothesisIn 1883, Julius Wellhausen published Prolegomena zur Geschichte Israels (Prolegomena to theHistory of Israel). This was the foundation work of a school of thought regarding the authorship ofTorah. It is best known as the Documentary Hypothesis, or JEPD. Later scholarship rejected some ofhis ideas, but the general ideas are now widely accepted. I will present these ideas in their most generalform, but still use the recognized term Documentary Hypothesis. The idea of Wellhausen mostcommonly rejected is the idea that each source was a complete, consistent written text on its own.Don't try to forge clear delineations between sources in the texts. But don't ignore the sources. Theycan help understand the texts. I will stick with the term 'source' (rather than text or source text),especially since the Elohist source was very likely oral.I suggest understanding this division of the texts to improve our understanding of the texts themselves.The ideas were assembled and edited into what eventually became Tanakh, the Jewish canon, and mostspecifically, that part of the canon called Torah (Hebrew תוֹר ָה ּ literally, teaching or instruction). Whenyou see the word law in an English translation of the OT (and it's not brother-in-law), it's Strong's 8451,torah. The ideas came from different sets of people, at different times, and were written in differentstyles, often with different philosophical and historical contexts. Understanding the ideas of a text ismore likely to be correct when each is understood and interpreted in its own context, rather than tryingto force it into some other context.Modern biblical textual scholarship compares the biblical texts to themany other writings of the era, including those of the neighbors ofAncient Jewish Philosophy as Expressed in Tanakh, by Frank Nemec, page 9

Israel. The 'writing' of Torah was completed 600-400 CE. The language is Classical Hebrew, whichflourished during the Babylonian exile. Evidence of any writing in any form of Hebrew before that timeis scarce. The earliest extant candidate is from around 1000 BCE, the Khirbet Qeiyafa Ostracon. Therendition shown here by Michael Netzer was based on enhanced e:Khirbet Qeiyafa Ostracon.jpg These and the protoCanaanite symbols derived from Egyptian heiroglyphs from as early as the 32nd century BCE.Aggregation and various stages of redaction resulted in the Hebrew texts we have today in Tanakh.Scholars don't know whether one person did the final writing/editing, or whether a group of people wasinvolved. They drew material from at least these specific sources (written or not). The authors/editorsseemed to take care to preserve the thoughts and styles of the varying sources, while composing aunifying document. The fist image above (from tml)shows a rough timeline and path for the development of the text from the sources.The next below (from Wikimedia) shows one example of a possible assignment of sources to text. Thelast is from -development-timeline-004.gif which isin Arabic by a Syrian.Torah and Talmud were long considered too sacred to write down. The Jewish tradition of Oral Torahis that it was handed down by Moses on Sinai, memorized, and passed on by word of mouth. In myskeptical opinion, an alterior motive for not writing it was preserving the freedom of leadership tochange it. Once it was written, it was much harder to change. Since the Jews had a very strong traditionof scribal integrity in preserving written Torah, I consider Torah an accurate representation of officialJewish beliefs at the time of writing and/or editing, with at least some effort to preserve, represent, ordescribe their beliefs earlier in history. This lets us trace the evolution of their beliefs over their history.Ancient Jewish Philosophy as Expressed in Tanakh, by Frank Nemec, page 10

It's also why I seek the best honest scholarly estimates of the actual time of writing. The dates of finalcomposition / editing indicate to me the dates of the ideas they represent. Dates of suggested possibleearlier sources or texts are much harder to assess. Since we don't have those texts or sources, we can'tcompare the preservation of ideas.2 Kings 22 shows Josiah (specifically Kilkiah the high priest) 'finding' Torah. Some suggest Josiah hadthe Deuteronomist create the laws requiring worship (therefore priestly power) to be concentrated intoJerusalem, and insert them into Torah.Jahwist sourceThis is the only source to use the personal name Yahweh (Jahweh in Wellhausen's German) earlier thanExodus 3. The consensus estimate is c. 950 BC (during the reign of Solomon), not long before the splitof the United Kingdom of Israel into the northern kingdom of Israel and the southern kingdom of Judahin 922 BC. Newer research suggests a date in the 7th century BC. It is represented by much of Genesis,beginning at 2:4b, portions of Exodus and Numbers, and a few short texts in Deuteronomy. It isassociated with the southern tribes of Judah.Ancient Jewish Philosophy as Expressed in Tanakh, by Frank Nemec, page 11

Elohist sourceThis source refers to God as Elohim, the plural form of El. See Folklore Analysis and Type Scenes formore detail. Scholars suggest c. 850 BC for this source. Genesis 15 seems to be the earliest. It isassociated with the northern tribes.Deuteronomist sourceThis source was likely composed during the Babylonian Captivity (587-539 BC), or before (c. 650-621BC). This may have been during the reign of Josiah (c. 641-610 BCE (or 640-610), 2 Kings 22). Mosthistorians credit Josiah with writing or compiling these texts during the Deuteronomic reform of hisreign. Deuteronomy, Joshua, Judges, and Kings are considered books from this source, with those afterDeuteronomy from the (perhaps different) Deuteronomistic history source.Priestly sourceThis source was likely composed c. 600-400 BC, during or shortly after the Babylonian Captivity, andis represented by about a fifth of Genesis (including 1:1-4a), much of Exodus and Numbers, andessentially all of Leviticus.Various factors, including comparing language features to peer literature, suggests that the redaction ofthese sources into the texts in the form we have now was complete around 450 BC.Genesis 14 seems to be from a completely different source. It contains alternative names for severalplaces, suggesting perhaps that an older account was reworded and inserted here. As noted underNames of God, Melchizedek (mentioned only here) is a Jebusite name, and Zedek the name of aJebusite god.You can learn more about this at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Documentary hypothesis and othersources. I think we can best understand the texts of the Bible when we know something about whowrote them, when they were written, and why they were written.Literary GenresPeople write to communicate their ideas. Authors choose a literary genre as the clay with which to moldtheir sculpture. Each genre embodies a set of socially-agreed-upon conventions. Communication worksbes

those thoughts are expressed in Tanakh (what Christians renamed as the Old Testament). These notes began as a framework for a class on the history of Israel as recorded in the Bible, and in the context of its peers, and as matched with history. The class met Sunday evenings 6:30-8pm in room 3191 at Valley