Transcription

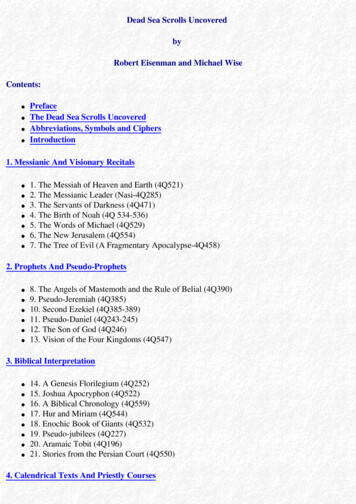

Table of ContentsPENGUIN BOOKS THE COMPLETE DEAD SEA SCROLLS INENGLISHTitle PageCopyright PageDedicationPrefaceIntroductionA. The RulesThe Community Rule - (IQS, 4Q255-64, 4Q280, 286-7, 4Q502, 5QII,13)Community Rule manuscripts from Cave 4Entry into the Covenant - (4Q275)Four Classes of the Community - (4Q279)The Damascus Document - (CD, 4Q265-73, 5Q12, 6Q15)Damascus Document manuscripts from Cave 4The Messianic Rule - (1QSa 1Q28a)The War Scroll - (IQM, 1Q33, 4Q491-7, 4Q471)The War Scroll from Cave 4 - (4Q491, 493)The Book of War - (4Q285, 11Q14)The Temple Scroll - (11QT 11Q19-21, 4Q365a, 4Q524)MMT (Miqsat Ma‘ase Ha- Torah) - Some Observances of the Law (4Q394-9)The Wicked and the Holy - (4Q181)4QHalakhah A - (4Q251)4QHalakhah B - (4Q264a)4QTohorot (Purities) A - (4Q274)

4QTohorot B-B - (40276-7)4Q Harvesting - (4Q284a)The Master’s Exhortation to the Sons of Dawn - (40298)4Q Men Who Err - (40306)Register of Rebukes - (4Q477)Remonstrances (before Conversion?) - (4Q471)B. Hymns and PoemsThe Thanksgiving Hymns - (IQH, IQ36, 4Q427-32)Hymnic Fragment - (4Q433a)Apocryphal Psalms (I) - (IIQPs IIQ5,4Q88)Apocryphal Psalms (II) - (4Q88)Apocryphal Psalms (III) - (11QapPs 11Q11)Non-canonical Psalms - (4Q380-81)Lamentations - (4Q]179,4Q501)Songs for the Holocaust of the Sabbath - (4Q400—407, 11Q17,Masada 1039-200)Poetic Fragments on Jerusalem and ‘King’ Jonathan - (4Q448 )Hymn of Glorification A and B - (4Q491, fr. 11—4Q471b)C. Calendars, Liturgies and PrayersCalendars of Priestly Courses - (4Q320-30, 337)Calendrical Document C - (4Q326)Calendrical Document D - (4Q394 1-2)Calendric Signs (Otot) - (4Q319)‘Horoscopes’ or Astrological Physiognomies - (4Q186, 4Q534,4Q561)Phases of the Moon - (4Q317)A Zodiacal Calendar with a Brontologion - (4Q318)Order of Divine Office - (4Q334)

The Words of the Heavenly Lights - (4Q504—6)Liturgical Prayer - (1Q 34 and 34 bis)Prayers for Festivals - (4Q 507-9)Daily Prayers - (4Q 503)Prayer or Hymn Celebrating the Morning and the Evening - (4Q 408)Blessings - (1QSb 1Q28b)Benedictions - (4Q 280, 286-90)Confession Ritual - (4Q393)Purification Ritual A - (4Q 512)Purification Ritual B - (4Q 4]14)A Liturgical Work - (4Q 392-3)D. Historical and Apocalyptic WorksApocalyptic Chronology or Apocryphal Weeks - (4Q 247)Historical Text A - (4Q248)Historical Texts C-E (formerly Mishmarot C) - 4Q331-3)Historical Text F - (4Q468e)The Triumph of Righteousness or Mysteries - (1Q27, 4Q299-3011)Time of Righteousness - (4Q 215a)The Renewed Earth - (4Q 475)A Messianic Apocalypse - (4Q521)E. Wisdom LiteratureThe Seductress - (4Q184)Exhortation to Seek Wisdom - (4Q185)A Parable of Warning - (4Q302)Sapiential Didactic Work A - (4Q412)A Sapiential Work (i) - (4Q413)A Sapiential Work (ii) - (4Q415-18, 423, 1Q26)A Sapiential Work (iii): Ways of Righteousness - (4Q420-21)

A Sapiential Work Instruction-like Composition - (4Q424)The Two Ways - (4Q473)Bless, My Soul - (Barki nafshi, 4Q434-438)A Leader’s Lament - (4Q439)Fight against Evil Spirits - (4Q444)Songs of the Sage - (4Q510-11)Beatitudes - (4Q525)F. Bible InterpretationAramaic Bible Translations - (Targums)The Targum of Job - (11Q10,4Q157)The Targum of LeviticusAppendixG. Biblically Based Apocryphal WorksJubilees - (4Q216-28, 1Q17-18, 2Q19-20, 3Q5, 4Q482(?), 11Q12)The Prayer of Enosh and Enoch - (4Q369)The Book of Enoch - (4Q201-2, 204-12)The Book of Giants - (1Q23-4, 2Q26, 4Q203, 530-33, 6Q8)An Admonition Associated with the Flood - (4Q370, 4Q185)The Ages of the Creation - (4Q180)The Book of Noah - (1Q19, 1Q19 bis, 4Q534-6, 6Q8,19)Words of the Archangel Michael - (4Q529, 6Q23)The Testament of Levi (i) - (4Q213-114, 1Q21)Testaments of the Patriarchs: the Testament of Levi or Testament ofJacob - .The Testament of Judah and Joseph - (4Q538-9)The Testament of Naphtali - (4Q215)Narrative and Poetic Composition (formerly ‘A Joseph Apocryphon’) (4Q371-3)

The Testament of Qahat - (4Q542)The Testament of Amram - (4Q543-9)The Words of Moses - (1Q22)Sermon on the Exodus and the Conquest of Canaan - (4Q374)A Moses Apocryphon - (4Q375)A Moses Apocryphon - (4Q376, 1Q29)A Moses Apocryphon - (4Q408)Apocryphal Pentateuch B (formerly ‘A Moses Apocryphon) - (4Q377)A Moses (or David) Apocryphon - (4Q373, 2Q22)Prophecy of Joshua - (4Q522, 5Q9)A Joshua Apocryphon (i) or Psalms of Joshua - (4Q378—9)A Joshua Apocryphon (ii) (Masada 1039—211)The Samuel Apocryphon - (4Q160)A Paraphrase on Kings - (4Q382)An Elisha Apocryphon - (4Q481)A Zedekiah Apocryphon - (4Q470)A Historico-theological Narrative based on Genesis and Exodus (4Q462—4)Tobit - (4Q196—200Apocryphon of Jeremiah - (4Q383, 385a, 387, 387a, 388a, 389—90)The New Jerusalem - (4Q554-5, 5Q15, 1Q32, 2Q24, 4Q232, 11Q18)Pseudo-Ezekiel - (4Q385, 386, 385b, 388, 385c)The Prayer of Nabonidus - (4Q242)Para-Danielic Writings - (4Q243-5)The Four Kingdoms - (4Q552-3)An Aramaic Apocalypse - (4Q246)Proto-Esther (?) - (4Q550)List of False Prophets - (4Q339)List of Netinim - (4Q340)H. MiscellaneaThe Copper Scroll - (3Q15)Cryptic Texts - (4Q249, 250, 313)

Two Qumran OstracaI. AppendixIndex of QumranTextsMajor Editions of Qumran ManuscriptsGeneral BibliographyGeneral IndexTHE STORY OF PENGUIN CLASSICS

PENGUIN BOOKS THE COMPLETE DEAD SEASCROLLS IN ENGLISHGeza Vermes was born in Hungary in 1924. He studied in Budapestand in Louvain, where he read Oriental history and languages and in1953 obtained a doctorate in theology with a dissertation on thehistorical framework of the Dead Sea Scrolls. From 1957 to 1991 hetaught in England at the universities of Newcastle upon Tyne (1957-65)and Oxford (1965—91). He is now Professor Emeritus of JewishStudies and Emeritus Fellow of Wolfson College, but continues toteach at the Oriental Institute in Oxford. He has edited the Journal ofJewish Studies since 1971, and since 1991 he has been director ofthe Oxford Forum for Qumran Research at the Oxford Centre forHebrew and Jewish Studies. Professor Vermes is a Fellow of theBritish Academy and of the European Academy of Arts, Sciences andHumanities. He is the holder of an Oxford D.Litt. and of honorarydoctorates from the universities of Edinburgh, Durham and Sheffield.His first article on the Dead Sea Scrolls appeared in 1949 and his firstbook, Les manuscrits du désert de Juda,in 1953. It was translatedinto English in 1956 as Discovery in the Judean Desert. He is also theauthor of Scripture and Tradition in Judaism (1961, 1973, 1983);Jesus the Jew (1973, 1976, 1981, 1983); The Dead Sea Scrolls:Qumran in Perspective (1977, 1981, 1982, 1994); Jesus and theWorld ofJudaism (1983, 1984); The Religion ofJesusthe Jew (1993);and (with Martin Goodman) The Essenes According to the ClassicalSources (1989); (with Philip Alexander) Discoveries in the JudaeanDesert XXVI (1998) and (also with Philip Alexander) XXXVI (2000);An Introduction to the Complete Dead Sea Scrolls (1999, 2000); TheDead Sea Scrolls (The Folio Society, 2000); The Changing Faces ofJesus (2000); The Authentic Gospel of Jesus (2003) and Jesus in hisJewish Context (2003). He played a leading part in the rewriting ofEmil Schiirer’s classic work The History of the Jewish People in theAge of Jesus Christ (1973-87). His autobiography, Providential

Accidents (1998), contains a vivid personal account of a life-longinvolvement with the Dead Sea Scrolls.

PENGUIN BOOKSPublished by the Penguin GroupPenguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R ORL, EnglandPenguin Putnam Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USAPenguin Books Australia Ltd, 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124,AustraliaPenguin Books Canada Ltd, 10 Alcorn Avenue, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4V 3B2Penguin Books India (P) Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi - 110017, IndiaPenguin Group (NZ), Cnr Airborne and Rosedale Roads, Albany, Auckland 1310, NewZealandPenguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank 2196, South AfricaPenguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R ORL, Englandwww.penguin.comFirst published in Pelican Books 1962Reprinted with revisions 1965, 1968Fourth edition published in Penguin Books 1995Complete edition published by Allen Lane The Penguin Press 1997Published in Penguin Books 1998Revised edition 200411Copyright G. Vennes, 1962, 1965, 1968, 1975, 1987. 1995, 1997, 2004All rights reservedThe extracts on pp. 95 and 247 are reproduced by kind permissionof the Israel Museum, Jerusalem; the extracts on pp. 345, 401, 415,459 and 537 are reproduced by kind permission of the IsraelAntiquities Authority; p. 581: a cut segment from The Copper Scrollfrom The Dead Sea Scrolls: A Reappraisal by John Allegro (PenguinMaps drawn by Nigel AndrewsThe moral right of the author has been asserted

eISBN : 978-1-101-16059-6www.greenpenguin.co.ukPenguin Books is committed to a sustainable future for our business, ourreaders and our planet.The book in your hands is made from paper certified by the Forest StewardshipCouncil.http://us.penguingroup.com

For M and I with love and in loving memory of P

PrefaceIn the spring of 1947 a young Arab shepherd climbed into a cave in theJudaean desert and stumbled on the first Dead Sea Scrolls. For thoseof us who lived through the Qumran story from the beginning, therealization that all this happened half a century ago brings with it amelancholy feeling. The Scrolls are no longer a recent discovery as weused to refer to them, but over the years they have grown insignificance and now the golden jubilee of the first manuscript find callsfor celebration with joy and satisfaction. Following the ‘revolution’which ‘liberated’ all the manuscripts in 1991 - until that moment a largeportion of them was kept away from the public gaze - every interestedperson gained free access to the entire Qumran library. I eagerlyseized the chance and set out to explore the whole collection. Today,after four and a half years of intense study, I feel confident that I canpresent the complete canvas of the Dead Sea Scrolls and disclose tothe many interested readers the message of these ancientmanuscripts about ancient Judaism and to a more limited extent aboutearly Christianity.In its successive editions this book has endeavoured to serve a dualaudience of scholars and educated lay people. Over the years it hasgrown in size - it contained only 255 pages in 1962 - and I trust also inits grasp of the subject. While this translation of the non-biblical Scrollsdoes not claim to cover every fragment retrieved from the caves, it iscomplete in one sense: it offers in a readable form all the textssufficiently well preserved to be understandable in English. In plainwords, meaningless scraps or badly damaged manuscript sectionsare not inflicted on the reader. Those who wish to survey textsconsisting only of broken lines, or of single letters and half-letters,should turn to the official series Discoveries in the Judaean Desert, inwhich every surviving detail is put on record.In addition to the English rendering of the Hebrew and Aramaic textsfound in the eleven Qumran caves, two inscribed potsherds (ostraca)

retrieved from the Qumran site and two Qumran-type documentsdiscovered in the fortress of Masada, and brief introductory notes toeach text, this volume also provides an up-to-date general introduction,outlining the history of fifty years of Scroll research and sketching theorganization, history and religious message of the QumranCommunity. A Scroll catalogue, an essential bibliography and an indexof Qumran texts are appended to facilitate further study and research.

Map 1: The area surrounding the Dead Sea, showing Qumran

Map 2: The Caves of QumranHas the greatly increased source material substantially altered ourperception of the writings found at Qumran? I do not think so. Nuancesand emphases have changed, but additional information has mainlyhelped to fill in gaps and clarify obscurities; it has not undermined ourearlier conceptions regarding the Community and its ideas. We hadthe exceptionally good fortune that all but one of the major non-biblicalScrolls were published at the start, between 1950 and 1956: theHabakkuk Commentary (1950), the Community Rule (1951), the WarScroll and the Thanksgiving Hymns (1954/5) and the best-preservedcolumns of the Genesis Apocryphon (1956). Even the Temple Scroll,which had remained concealed until 1967 in a Bata shoebox by anantique dealer, was edited ten years later. The large Scrolls haveserved as foundation and pillars, and the thousands of fragments asbuilding stones, with which the unique shrine of Jewish religion andculture that is Qumran is progressively restored to its ancientsplendour.Finally, it is a most pleasant duty to express my warmest thanks tofriends and colleagues who helped to make this book less imperfectthan it might otherwise have been. First and foremost, I wish publicly toconvey my gratitude to Professor Emanuel Tov, editor-in-chief of theDead Sea Scrolls Publication Project, for his generosity in answeringqueries and assisting in every possible way. My very special thanksare due also to Professor Joseph M. Baumgarten, who allowed me toconsult his edition of the Damascus Document fragments from Cave 4prior to their publication in DJD, and to my former pupil, Dr JonathanG. Campbell, who did not shirk the onerous task of reading throughand commenting on the rather bulky printout of this volume.G.V

Preface to the Penguin Classics editionSince the end of 1996, when the text of The Complete Dead SeaScrolls in English was sent to the printers, eighteen further tomes ofmanuscript material have appeared in the series Discoveries in theJudaean Desert (DJD).Today, in January 2003, only three morevolumes, two biblical and one non-biblical, still await publication beforethe 39-volume venture, begun in 1955 with DJD I, reaches its fulfilment.When reviewing The Complete Dead Sea Scrolls in 1997, John J.Collins wittily predicted: ‘It is not inconceivable that a more completeedition may appear a few years hence.’ Yet even today’s revised andupdated version remains in some way incomplete. It is without thescriptural texts found in the caves, which I never intended to include.Luckily these are now available in The Dead Sea Scrolls Bible issuedby Martin Abegg, Peter Flint and Eugene Ulrich (Harper SanFrancisco, 1999). Neither have I attempted at any stage to present theEnglish translation of every scrap devoid of significance (small,unconnected manuscript remains, broken sentences, single words,half-words or letters). However, I can state even more confidently than Idid seven years ago that the reader will find in this volume all that ismeaningful and interesting in the non-biblical Dead Sea Scrolls.The introductory chapters and the bibliographies have also beenbrought up to date so that account is taken in them of all fresh materialas well as of the continuous advance of Qumran research.The publishers have decided to provide this book with a new niche:forty-one years after its first appearance in 1962 in the Pelican series,it will have its home from now on next to the great works of worldliterature in the Penguin Classics library.I feel deeply honoured.Oxford, January 2003G.V

Chronology

I. IntroductionOn the western shore of the Dead Sea, about eight miles south ofJericho, lies a complex of ruins known as Khirbet Qumran. It occupiesone of the lowest parts of the earth, on the fringe of the hot and aridwastes of the Wilderness of Judaea, and is today, apart fromoccasional invasions by coachloads of tourists, lifeless, silent andempty. But from that place, members of an ancient Jewish religiouscommunity, whose centre it was, hurried out one day and in secrecyclimbed the nearby cliffs in order to hide away in eleven caves theirprecious scrolls. No one came back to retrieve them, and there theyremained undisturbed for almost 2,000 years.The account of the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls, as themanuscripts are inaccurately designated, and of the half a century ofintense research that followed, is in itself a fascinating as well as anexasperating story. It has been told many a time, but this fiftiethanniversary of the first Scroll find excuses, and even demands, yetanother rehearsal.1A BIRD’S-EYE VIEW OF FIFTY YEARS OF DEADSEA SCROLLS RESEARCH1. 1947-1967News of an extraordinary discovery of seven ancient Hebrew andAramaic manuscripts began to spread in 1948 from Israeli andAmerican sources.2 The original chance find by a young Bedouinshepherd, Muhammad edh-Dhib, occurred during the last months ofthe British mandate in Palestine in the spring or summer of 1947,unless it was slightly earlier, in the winter of 1946. 3 In 1949, the cave

where the scrolls lay hidden was identified, thanks to the efforts of abored Belgian army officer of the United Nations Armistice ObserverCorps, Captain Philippe Lippens, assisted by a unit of Jordan’s ArabLegion, commanded by Major-General Lash. It was investigated by G.Lankester Harding, the English Director of the Department ofAntiquities of Jordan, and the French Dominican archaeologist andbiblical scholar, Father Roland de Vaux. They retrieved hundreds ofleather fragments, some large but most of them minute, in addition tothe seven scrolls found in the same cave.Three of the rolls, an incomplete Isaiah manuscript, a scroll of Hymnsand one describing the War of the Sons of Light against the Sons ofDarkness, were purchased in 1947 by the Hebrew University’sProfessor of Jewish Archaeology, E. L. Sukenik, who proceeded at fullspeed towards their publication. The other four were entrusted forstudy and eventual publication by their owner, the Arab metropolitanarchbishop Mar Athanasius, head of the Syrian Orthodox monastery ofSt Mark in Jerusalem, to the resident staff of the American School forOriental Research in Jerusalem, Millar Burrows, W H. Brownlee and J.C. Trever. These three took charge of a complete Isaiah manuscript,the Commentary on Habakkuk and the Manual of Discipline, laterrenamed the Community Rule. Finally, after the splitting of Britishmandatary Palestine into Israel and Jordan, at the École Biblique etArchéologique Française in Jordanian Jerusalem two youngresearchers, the Frenchman Dominique Barthélemy and the PoleJózef Tadeusz Milik, were commissioned by de Vaux and Harding inlate 1951 to edit the fragments collected in Cave I.Between 1951 and 1956, ten further caves were discovered, mostof them by Bedouin in the first instance. Two yielded substantialquantities of material. Thousands and thousands of fragments werefound in Cave 4 and several scrolls, including the longest, the TempleScroll, were retrieved from Cave II. The previously neglected ruins of asettlement in the proximity of the caves were also excavated byHarding and de Vaux, and the view soon prevailed that the texts, thecaves and the Qumran site were interconnected, and that consequentlythe study of the script and contents of the manuscripts should beaccompanied by archaeological research.

Progress was surprisingly quick despite the fact that in thosehalcyon days, apart from the small Nash papyrus, containing the TenCommandments, found in Egypt and now in the Cambridge UniversityLibrary, no Hebrew documents dating to Late Antiquity were extant toprovide terms of comparison. In 1948 and 1949, Sukenik published inHebrew two preliminary surveys entitled Hidden Scrolls from theJudaeanDesert, and concluded that the religious community involvedwas the ascetic sect of the Essenes, well known from the first-centuryCE writings of Philo, Josephus and Pliny the Elder, a thesis workedout in great detail from 1951 onwards by André Dupont-Sommer inParis.4 The first Qumran scrolls to reach the public, and thearchaeological setting in which they were discovered, echoed threestriking Essene characteristics. The Community Rule, a basic code ofsectarian existence, reflects Essene common ownership and celibatelife, while the geographical location of Qumran tallies with Pliny’sEssene settlement on the north-western shore of the Dead Sea, southof Jericho. The principal novelty provided by the manuscripts consistsof cryptic allusions to the historical origins of the Community, launchedby a priest called the Teacher of Righteousness, who was persecutedby a Jewish ruler, designated as the Wicked Priest. The Teacher andhis followers were compelled to withdraw into the desert, where theyawaited the impending manifestation of God’s triumph over evil anddarkness in the end of days, which had already begun.An almost unanimous agreement soon emerged, dating thediscovery, on the basis of palaeography and archaeology, to the lastcenturies of the Second Temple, i.e. second century BCE to firstcentury CE. For a short while there was controversy between de Vaux,who decreed that the pottery and all the finds belonged to theHellenistic era (i.e. pre-63 BCE), and Dupont-Sommer, who argued foran early Roman (post-63) date. But the finding of further caves and theexcavation of the ruins of Qumran brought about, on 4 April 1952, deVaux’s dramatic retraction before the French Académie desInscriptions et Belles-Lettres. His revised archaeological synthesis,presented in the 1959 Schweich Lectures of the British Academy,while admittedly incomplete, is still the best comprehensive statementavailable today.5

A third point of early consensus concerns the chronology of theevents alluded to in the Qumran writings, especially the biblicalcommentaries published in the 1950S and the Damascus Document.The so-called Maccabaean theory, placing the conflict between theTeacher of Righteousness and the politico-religious Jewish leadershipof the day in the time of the Maccabaean high priest or high priestsJonathan and/or Simon, was first formulated in my 1952 doctoraldissertation, published in 1953,6 and was soon to be adopted withvariations in detail by such leading specialists as J. T. Milik, F. M.Cross and R. de Vaux.7As long as the editorial task consisted only of publishing the sevenscrolls from Cave I, work was advancing remarkably fast. MillarBurrows and his colleagues published their three manuscripts in 1950and 1951.8 Sukenik’s three texts appeared in a posthumous volume in1954-5.9 In the interest of speed, these editors generously abstainedfrom translating and interpreting the texts, and were content withreleasing the photographs and their transcription. The best-preservedsections of the Aramaic Genesis Apocryphon followed closely in1956.10 Even the fragments from Cave I, handled with alacrity andloving care by D. Barthélemy and J. T Milik, appeared in 1955.11 Thesecrecy rule of later years, restricting access to unpublished texts to asmall team of editors appointed by de Vaux, had not yet been applied.On my first visit to Jerusalem in 1952, I was allowed to examine thefragments of the Rule of the Congregation (1QSa), as may be seenfrom the inclusion in the final edition of a reading suggested by me tothe editors.The scroll fragments, partly found by the archaeologists, but mostlypurchased from the Arabs, who nine times out of ten outwitted theirprofessional rivals, were cleaned, sorted out and displayed in the socalled Scrollery in the Rockefeller Museum, later renamed thePalestine Archaeological Museum, to become after 1967 once morethe Rockefeller Museum. If the mass of material disgorged by Cave 4had not upset the original arrangements, the scandalous delays inpublishing in later years need never have happened.To deal with Cave 4, Father de Vaux improvised, in 1953 and 1954,

a team of seven on the whole young and untried scholars. Barthélemyopted out, and the brilliant but unpredictable Abbé J. T. Milik, who laterleft the Roman Catholic priesthood, became the pillar of the newgroup. He was joined by the French Abbé Jean Starcky, and twoAmericans, Monsignor Patrick Skehan and Frank Moore Cross. JohnMarco Allegro and John Strugnell were recruited from Britain, and fromGermany, Claus-Hunno Hunzinger, who soon resigned and wasreplaced later by the French Abbé Maurice Baillet.It should have been evident to anyone with a modicum of goodsense that a group of seven editors, of whom only two, Starcky andSkehan, had already established a scholarly reputation, wasinsufficient to perform such an enormous task on any level, let alone toproduce the kind of ‘last word’ edition de Vaux appears to havecontemplated. The second serious error committed by de Vaux wasthat he wholly relied on his personal, quasi-patriarchal authority,instead of setting up from the start a supervisory body empowered, ifnecessary, to sack those members of the team who might fail to fulfiltheir obligations promptly and to everyone’s satisfaction.Yet before depicting the chaos characterizing the publishingprocess in the 1970s and 1980s, in fairness it should be stressed that,during the first decade or so, the industry of the group could notseriously be faulted. Judging from the completion around 1060 of aprimitive Concordance, recorded on handwritten index cards, of all thewords appearing in the fragments found in Caves 2 to 10, it is clearthat at an early date most of the texts had been identified anddeciphered. The many criticisms advanced in subsequent years,focusing on these scholars’ refusal to put their valuable findings intothe public domain, should not prevent one from acknowledging that thisoriginal achievement, in which J. T. Milik had the lion’s share, deservesunrestricted admiration.After the publication of the Cave I fragments in 1955, the contents ofthe eight minor caves (2-3, 5-10) were released in a single volume in1963.12 In 1965 J. A. Sanders, an American scholar who was not partof the original team, edited the Psalms Scroll, found in Cave II in1956.13 Finally, with its typescript completed and dispatched to theprinters a year before the fatal date of 1967, the first poorly edited

volume of Cave 4 fragments saw the light of day in 1968.142. 1967-1990With the occupation of East Jerusalem in the Six Day War, all the scrollfragments housed in the Palestine Archaeological Museum cameunder the control of the Israel Department of Antiquities. Only theCopper Scroll and a few other fragments exhibited in Ammanremained in Jordanian hands. The Temple Scroll, which until then hadbeen held by a dealer in Bethlehem,15 was quickly retrieved with thehelp of army intelligence and acquired by the State of Israel. YigaelYadin, deputy prime minister of Israel in the 1970s, mixing politics withscholarship, managed to complete a magisterial three-volumepublication by 1977.16A gentlemanly gesture on the part of the Israelis, who decided not tointerfere with de Vaux, left him and his scattered troop in charge of theCave 4 texts.17 As for the unpublished manuscripts from Cave II, theywere handled by Dutch and American academics.18Father de Vaux, whose anti-Israeli sentiments were no secret,quietly withdrew to his tent and remained inactive until his death in1971. Another French Dominican, Pierre Benoit, succeeded him as itwere by natural selection in the editorial chair in 1972. The Israeliarchaeological establishment, still aloof, conferred its blessing on him.By then, at my instigation, C. H. Roberts, Secretary to the Delegates,i.e. chief executive of Oxford University Press, decided to demandspeedier publication, but Benoit’s ineffectual rallying call either elicitedno response from his men, or produced promises which were neverhonoured.19 In a lecture delivered in 1977, I coined the phrase whichwas thereafter often repeated that the greatest Hebrew manuscriptdiscovery was fast becoming ‘the academic scandal par excellence ofthe twentieth century’.20One may ask how and why, after such an apparently propitiousbeginning, a group of scholars, most of whom were gifted, had turnedthe editorial work on the Scrolls into such a lamentable story? In my

opinion, the ‘academic scandal of the century’ resulted from aconcatenation of causes. Lack of organization and unfortunate choiceof collaborators can be blamed on de Vaux. For the majority of theteam members who had other jobs to cope with, the overlong part-timeeffort caused their original enthusiasm to fade and vanish. J. T. Milik,the most productive of them until the mid-seventies, appears to havebeen disenchanted by the cool reception of his highly speculativethesis contained in his edition of The Books ofEnoch:AramaicFragments of Qumran Cave 4(1976). ‘Academic imperialism’ wasalso a factor. It was easier to hold that ‘These texts belong to us, not toyou!’ than to admit that the procrastinating editors had undertakenmore than they could deliver. Add to this the initial unwillingness of theIsraelis to shoulder their responsibilities, and, as will be shown, theirlack of foresight and repeated misjudgements before, finally, in the late1980s, they began to take an active part in matters of editorial policy.Need I say more?The inevitable began to happen: in 1980 Patrick Skehan died,followed by Jean Starcky in 1986, both without publishing theirassignments. Eugene Ulrich and Emile Puech became their heirs,while F. M. Cross and J. Strugnell distributed portions of their texts toserve as dissertation topics for doctoral students at Harvard University.Though responsible for some good, and occasionally excellent,monographs, this unfortunate practice further delayed progress asthesis writers like to keep their cards close to their chests until theirPhDs are in the bag.In 1986, a year before his death, Pierre Benoit resigned as editorin-chief and the depleted international team elected as his successorthe talented but tardy John Strugnell, who in thirty-three years failed toproduce a single volume of text. In 1987, at a public session of aScrolls Symposium held in London, I urged him to publish at once thephotographic plates, while he and his acolytes carried on with theirwork at their customary snail pace. This request was met with a onesyllable negative answer. To the surprise of many, the Israel

His first article on the Dead Sea Scrolls appeared in 1949 and his first book, Les manuscrits du désert de Juda,in 1953. It was translated into English in 1956 as Discovery in the Judean Desert. He is also the author of Scripture and Tradition in Judaism (1961, 1973, 1983); Jesus the Jew (1973, 1976, 1981, 1983); The Dead Sea Scrolls: