Transcription

263Empirical test of the Lancastercharacteristics modelBerend WIERENGA*1. IntroductionThe ‘New Economic Theory of ConsumerBehaviour’ (Lancaster 1966, 1971) is an important developmentin the way economistslook at the consumer. This approach, alsocalled the CharacteristicsModel, was especially welcomed(Nicosia 1974; Ratchford1975) because of its multidimensionalorientation. A product is conceived of as a bundle ofcharacteristics that have want-satisfyingproperties to the consumer. This multidimensionalview can directly be linked to the multi-attribute models which have been developed bythe behavioral science-orientedconsumer researchers.Although the important contributionof thecharacteristicsmodel is the improvementoffundamentalinsight in consumer behavior,the model can also be used as a basis fornormativemodels for the developmentofprofit maximizing new products (Hauser andSimmie 1981) and for the formulationofnormative recommendationsto defend existing productsagainst competitiveentrants* ter)fakulteitBedrijfskunde,Postbus1738, 3000 DR Rotterdam,The Netherlands.The author wishes to thank Jaap Bijkerkand Gerard Verwey(AgriculturalUniversityWageningen)for their computerassistanceand SOCMARB.V. (ResearchInternational)fortheir cooperationin the data collectionprocess. Useful comments and suggestionswere obtainedfrom Leigh McAlister(MIT)and from an anonymousreviewer.Acceptedby Philippe Naert.Intern. J. of ResearchNorth-Holland0167-8116/84/ 3.00in Marketing0 1984, Elsevier1 (1984)Science263-293Publishers(Hauser and Shugan 1983; Hauser and Gaskin1983). Various suggestions have been madewith respect to empirical applicationsof theLancaster characteristicsmodel (Ratchford1975: 70-71). Up to now a few examples ofempirical studies in the Lancaster frameworkhave appeared in the literature: Ryans (1974),Ratchford (1980), Hauser and Gaskin (1983).In these examples the characteristicsmodelhas been applied to ‘one-shot purchases’, i.e.situations where the consumer chooses oneproduct from a set of alternatives. Ratchford(1979) has shown that the Lancaster modelcan be accommodatedto this situation. Thereal spirit of the model however, is in theexplanationof purchases of combinationsofdifferent products. McAlister(1979) has reported about an empirical study in this area,without reference to the Lancaster frameworkthough. Up to now no complete operationalization of the Lancaster model in this empirical setting seems to have been carried out.This paper presents such an operationalization for the case of choice of combinationsofvegetables by consumers in The Netherlands.Judging from the several examples about foodproducts given in this book (Lancaster 1971)vegetables should constitute a natural productfor applicationof the Lancaster model. Thevarious elements of the Lancaster model willbe measured and we will examine how wellthis model can explain and predict combinations of vegetables, purchased by consumersfor a one-week period.However, from the outset it was clear thattwo limitationsof the originalLancastermodel would probably be too restrictive toprovide a successful explanation.As has been argued by several authors(Nicosia (1974: 166), Ratchford(1975: 67),B.V. (North-Holland)

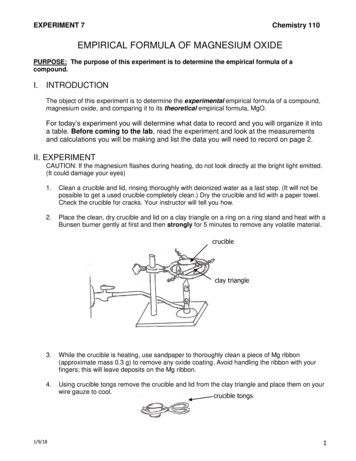

264B. Wierengu/ Empiricultest of the LumzsterHauser and Simmie (1981: 36)), Lancasterignores the perception process, i.e. the notionof ‘perceived characteristics’.From information processing theory we know that perceived characteristicsmay well differ fromtheir physical counterparts and that some perceptual dimensionsare more the result ofsocio-psychologicalcues produced by advertising, consumereducationand word-ofmouth communication,than of the physicalproperties of products. This does not invalidate the Lancaster model but requires anextension with a ‘perceptionmodule’. TheLancaster model has especially been welcomedbecause - through its multidimensionalorientation - it has offered a frameworkwithwhich to link the economic theory of consumer behavior with the multi-attributemodels developed by the behavioral science-oriented consumer researchers becomes possible.The use of (psychologicallybased) multidimensional scaling models of product perception within the frameworkof the Lancastermodel, as to be applied in this paper, exemplifies these integration possibilities.A second element, resulting from recentinsights into consumer behavior, not represented in the Lancaster model, is variety seeking behavior which plays a role in many consumer purchasingdecisions.Althoughavariety drive in consumer behavior has beenreferred to in the past (Berlyne (1960), Howard and Sheth (1969), Wierenga (1974, ch. 6)),the topic has recently received more attention: Faison (1977), Jeuland (1978), Howard(1980), McAlister and Pessemier (1982). It ispossible that a consumer acquires utility fromthe consumptionof many different items assuch, in addition to the consumptionof thecharacteristics levels implied by the combinations of items. Such an independentvalue ofvariety is not accommodatedfor in the standard characteristicsmodel. This paper presents an extension which makes it possible todetermine the importance of this variety driveand integratesit with the characteristicschorrrcteristicsmodelmodel. The Lancaster model with these twoextensions is operationalizedand tested for itsexplanatory power in this paper.2. The Lancastermodel and extensions2.1. The standard modelThe Lancaster model assumes a linear relationship between (physical) characteristics andproducts according to the expression:YYBI Bx,(r x 1) vector of characteristics,(r X n) ‘matrix of consumptionnology’, X(n X 1) vector of products,(i 1, . .) r) is the amount ofY, acteristic i,x, (j 1, . .) n) is the quantity ofuct j,bjj the amount of characteristicsstandard unit of product j.tech-charprodi per(1)If it is assumed that there is a budgetconstraint X, and the prices of the productsare p,(j l,. . . . n) the feasible region ofcharacteristics combinationsdetermined by Kand pl, . . . , p, can be indicated in the characteristics space. For the case of two characteristics and four hypothetical products thisis illustratedin figure 1. For example, thearrow with the number 1 represents the characteristics combinationthat can be boughtwhen the whole budget is allocated to product1. The coordinates of this point are: Kb,,/p,and Kb,,/p,.In figure 1 the products, 1, 2and 4 are efficient. Product 3 is not efficient,because spending the budget on combinationsof products 2 and 4 gives higher levels of bothcharacteristics 1 and 2 than buying product 3.The curve, connecting the arrows 1, 2 and 4 iscalled the ‘efficiency frontier’.Accordingto the theory, only efficientcombinationsof productsare purchased.Which of these combinationsare ultimately

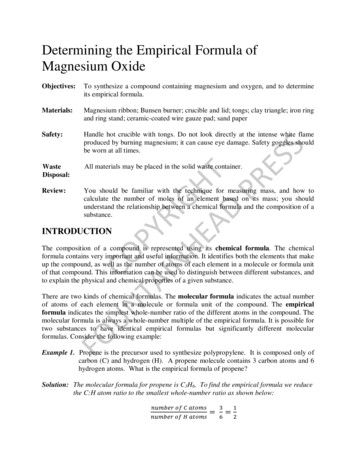

B. Wierengu/Empiricultest of the Lmxasterchoructeristicsmodel265frontierFigure1. Optimizationin the characteristicsmodelwith2 characteristicschosen depends on the utility functions andthe indifference curves of the consumers. Forexample, in figure 1 a consumer with indifference curve C,-C, would purchase a combination of the products 1 and 2, a consumerwith indifference curve C,,-C,, buys a combination of products 2 and 4 and a consumerwith indifferencecurve C,,,-C,,,will onlybuy product 2.Algebraically,in the Lancaster model aconsumer purchases the quantity for whichthe utility function U(v) is maximum, giventhe budget constraint. The optimizationproblem is solved thus:max U( y ),y Bx,xjTy; O.andsuch that(2)(3)(5)Figure 2 gives a schematic representationofthe standard Lancaster model. It shows thatthe physical features of the products, given bythe consumptiontechnology relationshipy Bx, together with the prices determine theefficient combinations.The optimal combination to be chosen from these efficient combinations is then determined by the utility func-and 4 products.tion and the budget constraint. With respectto the characteristics, Lancaster assumes ‘ universality and objectivity’(1971: 18); ‘everyconsumer in the economy is assumed to seethe same consumptiontechnology’ and ‘. . .there is no difference between them as towhat collection of characteristics is associatedwith any specified collectionof goods’. Ofcourse, a major problem is to determine thecharacteristics.Lancaster (1971: 115) : ‘ Ourfundamentaloperational problem is determining the relevant characteristicsfor choice’.The advantages of the characteristicsmodelare much greater when the number of relevantcharacteristicsis relativelylow: Lancaster(1971: 140). Lancaster assumed much moreheterogeneity with respect to preferences thanwith respect to the assessment of products(ibid.: 7): ‘Individualsdiffer in their reactionsto different characteristics rather than on theirassessment of the characteristicscontent ofvarious goods collections’. It is importanttoexamine these assumptions in practical applications. It is also importantto check twoimplicationsof the model: (i) dominatedproducts, i.e. products not on the efficiencyfrontier will not be bought, and (ii) the number of different product bought by one consumer is smaller than or equal to the numberof relevant characteristics.

B. Wierenga266/ Empiricaltest of the LancasterKpj(j l.n)y teristicsEfficientcombinationsof . . .I,rUtility(Preference)functionIJ (Y)Figure2. Schematicrepresentation2.2. The extended Lancasterof the StandardLancaster-modelmodelPerceived characteristics. The utility a consumer obtains from consuming a product or acombinationof products is determined by thecharacteristicshe or she attributesto theproducts in question. The variables that shouldenter the utility function are the characteristics as the consumer sees them. As referred toearlier, the perceived characteristics may wellbe at variance with objective, physical attributes of the products. The transformationofphysical productattributesinto perceivedcharacteristicscan be described by a matrixH (see also Hauser and Simmie 1981: 37):Y* ZH,(6)where Z is a (n X r) matrix of physical attributes, H is a (r x rp) transformationmatrixand YP is the matrix of perceived characteristics, derived from physical attributes.Thenumber of relevant physical attributes is r,the number of perceived characteristics,derived from physical attributes is rp, rp may ormay not be equal to r. Furthermore,throughsocio-psychologicalcues (publicity,advertising, consumer education)properties can beattributedto a product that have no directrelationshipwith physicalattributes:e.g.status-appeal of a product. We indicate suchsocio-psychologicaldimensions with the matrix Y”. The ultimate perceived characteristicsmatrix of a product is then: ’Y y* YS;(7)The matrix Y indicates how much a product has of a specific characteristic (in the eyesof the consumer). So Y can be considered asthe ‘perceived matrix of consumptiontechnology’. Y can be found by means of multidimensional scaling methods.Variety seeking behavior. Two types ofvariety seeking consumer behavior have beendistinguished (McAlister and Pessemier 1982).Derived variation is variation in consumption patterns not for the purpose of variationas such but as a ‘by-product’of other phenomena, for example multiple needs, multipleusers, multiple situations.1 When there are r relevant perceivedcharacteristics,of whichrP are derived from physicalattributesand r, from socio-psychologicalcues (r rP rs), Y can be assumedto be a(n X r) matrix of which the last r, columnsare zero and YP a(n X r) matrix of which the first r,, conlumnsare zero.

B. Wierenga/ Empiricaltest of the LancasterDirect variation is caused by the need forvariety as such. Novelty and change may bepursued as goals in itself. Consumers mayvary the products independentof the (perceived) characteristicscontent of the products. This can be linked to the standardLancaster model in the following way. In the‘standard’situationthe consumer buys acombinationonly for its characteristics content. The resulting combinationof items (xi,. .) xI) - the solution of the optimizationproblem (2)-(5) - is called here the standardmodel solution. When, apart from characteristics utility, also variety over products plays arole, this can be modeled by adding a term tothe objective function(eq. (6)) which expresses the variety level implied by a specificcombination(xi, . . . , xn) of items. Let thevariety level be indicated by V(x). The optimization problem then becomes:max wU(y) (1 - w)V(x),y Bx,andsuch that PjX, K,xj’y; o.01)Here w (0 w G 1) expresses the relativeweight a consumer attaches to characteristicsutility and variety respectively. We call thisthe Variety Seeking Model. Eq. (8) impliesthat variety seeking is a matter of degree: forw 1 there is no variety drive at all (theStandard Model is a special case of the VarietySeeking Model), for w 0 choice behavior iscompletelydeterminedby the desire forvariety, whatever the implied characteristicsof the product. For 0 w 1 consumer behavior can be seen as a compromise of obtaining utility from characteristics and striving forvariety. An importantissue is then how todefine the variety level V(x). A natural choice(Pessemier 1981) is to use an information-theoretical measure, e.g. 2j l- qjxj In qixj,where02)model26-lqj PI/K.(13)So qjxj is the proportionof the budget goingto product j. Another possibility is to lookdirectly at the vector x and to consider thevariance over the components xi to x,. In asituation where the entire purchases are concentrated on one vegetable, e.g. xj 0 andxi 0 for i j, the variance in the vector x ismaximum. However, when all vegetables arebought in the same quantities, i.e.x1 x* . . . x,,(14the variance in x equals zero. So a drive fordirect variety can be translated into a strivingfor a low variance in the vector x. This implies that in eq. (8) the variety measure shouldbe defined as:V(x)

The ‘New Economic Theory of Consumer Behaviour’ (Lancaster 1966, 1971) is an im- portant development in the way economists look at the consumer. This approach, also called the Characteristics Model, was espe- cially welcomed (Nicosia 1974; Ratchford 1975) because of its multidimensional orienta- tion. A product is conceived of as a bundle of characteristics that have want-satisfying prop .