Transcription

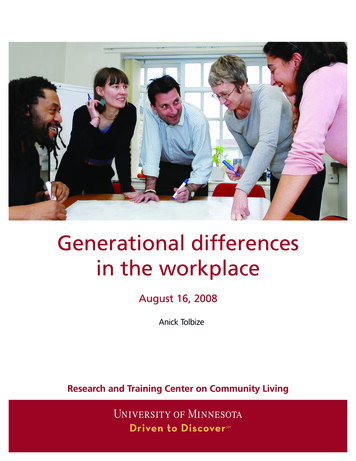

Generational differencesin the workplaceAugust 16, 2008Anick TolbizeResearch and Training Center on Community Living

Preparation of this manuscript was supported by the Centers on Medicaid and Medicare Services through a Subcontractfrom the Lewin Group’s Direct Support Worker Resource Center to the Research and Training Center on CommunityLiving at the University of Minnesota (Contract: TLG — 05-034-2967.06).

ContentsIntroduction / p. 1Four generations of American workers / p. 2The Traditional generation / p. 2The Baby Boom generation / p. 2Generation X / p. 3Generation Y / p. 4Possible generational differences and similarities / p. 5Attitudes towards work / p. 5Loyalty towards the employer / p. 6Attitudes regarding respect and authority / p. 7Training styles and training needs / p. 7Desire for a better work/life balance / p. 10Attitudes towards supervision / p. 10Other sources of differences / p. 10Implications for employers / p. 13Management / p. 13Communication and respect / p. 13Training and learning / p. 14Retention / p. 14Endnotes / p. 16References / p. 17Additional resources to deal with an intergenerational workforce / p. 19A. All generations / p. 19B. The Baby Boomers / p. 19C. Generation X / p. 19D. Generation Y / p. 20Additional resources / p. 20

Generational differences in the workplaceIntroductionWorking age Americans in 2008 fell into fourmain generations, a generation being definedas an identifiable group that shares birth years,age, location, and significant life events at criticaldevelopmental stages, divided by five to sevenyears into: the first wave, core group, and last wave(Kupperschmidt, 2000). There are at least two viewsregarding generational differences in the workplace.The first presumes that shared events influenceand define each generation (Zemke, Raines, &Filipczak, 2000) and that while individuals in differentgenerations are diverse, they nevertheless sharecertain thoughts, values, and behaviors becauseof the shared events. Furthermore, these values,reactions, and behaviors presumably differ acrossgenerations. The alternative view postulates thatalthough there might be variations throughoutan employee’s life cycle or career stage, ultimatelyemployees may be “generic” (Jurkiewicz & Brown,1998, p.29) in what they want from their jobs andtrying to bifurcate employees by generations may bemisguided (Jorgensen , 2003; Jurkiewicz & Brown,1998; Yang & Guy, 2006). In this paper, the fourgenerations of American workers are described,generational differences and similarities are identified,and implications for employers are discussed.1

2Generational differences in the workplaceFour generations of American workersThe Traditional generationThe Traditional generation is the oldest generationin the workplace, although most are now retired.Also known as the veterans, the Silents, the Silentgeneration, the matures, the greatest generation,this generation includes individuals born before1945, and some sources place the earliest birth yearto 1922 (www.valueoptions.com). Members of thisgeneration [hereinafter Traditionals] were influencedby the great depression and World War II amongother events and have been described as beingconservative and disciplined, as having a sense ofobligation, and as observing fiscal restraint (Niemic,2002). They have been described as liking formalityand a top down chain of command, as needingrespect, and as preferring to make decisions basedon what worked in the past (Kersten, 2002). TheNational Oceanographic and Atmospheric AssociationOffice of Diversity (2006) characterized members ofthis generation as the private, silent generation, whobelieve in paying their dues, for whom their word istheir bond, who prefer formality, have a great deal ofrespect for authority, like social order and who lovetheir things and tend to hoard stuff. Members ofthis generation have also been characterized as loyalworkers, highly dedicated, averse to risk and stronglycommitted toward teamwork and collaboration. Theyhave also been described as having a high regard fordeveloping communication skills, and as the mostaffluent elderly population in the U.S., due to theirtendency to save and conserve (Jenkins, 2007). Atwork, they are presumed to show consistency anduniformity, seek out technological advancements,be past-oriented, display command-and-controlleadership reminiscent of military operations, andprefer hierarchical organizational structures. They arelikely to continue to view horizontal structures in ahierarchical way (www.valueoptions.com). They arealso likely to be stable, detail oriented, thorough,loyal, and hard working, although they may be ineptwith ambiguity and change, reluctant to buck thesystem, uncomfortable with conflict, and reticentwhen they disagree (Zemke et al., 2000).The Baby Boom generationMost sources identify Baby Boomers as people bornbetween 1943 and 1965. The U.S. Census Bureaudefines Baby Boomers [Hereinafter ‘Boomers’] asindividuals born between 1946 and 1964. The BabyBoom generation has also been referred to as the“pig-in-the-python” (Callanan & Greenhaus, 2008).This generation is referred to as the Baby Boom,because of the extra seventeen million babies bornduring that period relative to previous census figures(O’Bannon, 2001). It has had the largest impacton American society due to its size — roughly 78million- and the period during which it came of age.Boomers witnessed and partook in the political andsocial turmoil of their time: the Vietnam War, the civilrights riots, the Kennedy and King assassinations,Watergate and the sexual revolution (Bradford,1963) as well as Woodstock (Adams, 2000) andthe freewheeling 60’s (Niemiec, 2000). Protestingagainst power characterized the formative years ofmany of the individuals now in leadership positions innumerous organizations.Boomers were raised to respect authority figures,but as they witnessed their foibles, learned not to“trust anyone over 30” (Karp, Fuller, & Sirias, 2002).They grew up in an era of “prosperity and optimismand bolstered by the sense that they are a specialgeneration capable of changing the world, haveequated work with self-worth, contribution andpersonal fulfillment” (p.270.Yang & Guy, 2006). Theoldest Baby Boomers turned 62 in 2008, and as awhole, this generation is now in the mid to late partof their careers. The entirety of this generation willreach the traditional retirement age of 65 within thenext 25 years (Callanan & Greenhaus, 2008).

Generational differences in the workplaceBoomers have been characterized as individualswho believe that hard work and sacrifice are theprice to pay for success. They started the workaholictrend (Glass, 2007; The National Oceanographic andAtmospheric Association Office of Diversity, 2006;Zemke et al., 2000) believe (d) in paying their duesand step-by-step promotion (CLC, 2001; Rath, 1999).They also like teamwork, collaboration and groupdecision-making (The National Oceanographic andAtmospheric Association Office of Diversity, 2006);www.valueoptions.com; Zemke et al., 2000), arecompetitive (Niemic, 2002) and believe in loyaltytoward their employers (Karp et al., 2002).Boomers are often confident task completers(www.valueoptions.com), and may be insulted byconstant feedback (The National Oceanographicand Atmospheric Association Office of Diversity,2006), although they want their achievement tobe recognized (Glass, 2007). Some have describedthem as being more process- than result-oriented(Zemke et al., 2000), although they have alsobeen characterized as being goal-oriented (www.valueoptions.com). Many are accepting of diversity(The National Oceanographic and AtmosphericAssociation Office of Diversity, 2006), optimistic(Zemke et al., 2000), liberal (Niemic, 2002), andconflict avoidant (Zemke, et al., 2000; valueoptions.com). They value health and wellness as well aspersonal growth and personal gratification (Zemke etal., 2000), and seek job security (Rath, 1999).Finally, Boomers have been described as havinga sense of entitlement, and as being good atrelationships, reluctant to go against peers andjudgments of others who do not see things theirway (Zemke et al., 2000). They also thrive on thepossibility for change, have been described as theshow me generation, and will fight for a cause eventhough they do not like problems (The NationalOceanographic and Atmospheric Association Officeof Diversity, 2006). They value the chain of command,may be technically challenged and expect authority(Rath, 1999).3Generation XIn a study about the civic engagement of GenerationX, the U.S. Census Bureau defined this segmentof the population as consisting of individuals bornbetween 1968 and 1979. However, the upper limitof Generation X in some cases has been as high as1982, while the lower limit has been as low as 1963(Karp et al., 2002). This generation was also calledthe baby bust generation, because of its small sizerelative to the generation that preceded it, the BabyBoom generation. The term Generation X spread intopopular parlance following the publication of DouglasCoupland’s book about a generation of individualswho would come of age at the end of the 20thcentury.Members of Generation X [Hereinafter Xers] arethe children of older boomers, who grew up in aperiod of financial, familial and societal insecurity.They witnessed their parents get laid off and thedecline of the American global power. They grew upwith a stagnant job market, corporate downsizing,and limited wage mobility, and are the first individualspredicted to earn less than their parents did. Theyhave grown up in homes where both parents worked,or in single parent household because of high divorcerates, and as such, became latchkey kids forced tofend for themselves (Karp et al., 2002). They wereinfluenced by MTV, AIDS and worldwide competitionand are accustomed to receiving instant feedbackfrom playing computer and video games (O’Bannon,2001).Among the characteristics attributed to Xers,the following appear most often. They aspire morethan previous generations to achieve a balancebetween work and life (Jenkins, 2007; Karp etal, 2002; www.valueoptions.com) they are moreindependent, autonomous and self-reliant thanprevious generations (Jenkins, 2007; Zemke et al.,2000) having grown up as latchkey kids. They are notoverly loyal to their employers (Bova & Kroth, 2001;Karp et al, 2002; The National Oceanographic andAtmospheric Association Office of Diversity, 2006)although they have strong feelings of loyalty towardstheir family and friends (Karp et al., 2002). They value

4Generational differences in the workplacecontinuous learning and skill development (Bova &Kroth, 2001). They have strong technical skills (Zemkeet al., 2000), are results focused (Crampton & Hodge,2006), and are “ruled by a sense of accomplishmentand not the clock” (Joyner, 2000). Xers naturallyquestion authority figures and are not intimidated bythem (The National Oceanographic and AtmosphericAssociation Office of Diversity, 2006; Zemke et al.,2000). Money does not necessarily motivate membersof this generation, but the absence of money mightlead them to lose motivation (Karp et al., 2002). Theylike to receive feedback (The National Oceanographicand Atmospheric Association Office of Diversity,2006), are adaptable to change (Zemke et al., 2000)and prefer flexible schedules (Joyner, 2000). They cantolerate work as long as it is fun (Karp et al., 2002).They are entrepreneurial (The National Oceanographicand Atmospheric Association Office of Diversity,2006), pragmatic (Niemiec, 2002), and creative(The National Oceanographic and AtmosphericAssociation Office of Diversity, 2006). Although theyare individualistic, they may also like teamwork, moreso than boomers (Karp et al., 2002).Generation YThe lower limit for Generation Y may be as low as1978, while the upper limit may be as high as 2002,depending on the source. Members of GenerationY may include individuals born between 1980 and1999 (Campton & Hodge, 2006); 1978 and 1995(The National Oceanographic and AtmosphericAssociation Office of Diversity, 2006); 1980 and 2002(Kersten, 2002); and 1978 and 1988 (Martin, 2005).The label associated with this generation is not yetfinalized. Current labels include Millenials, Nexters,Generation www, the Digital generation, GenerationE, Echo Boomers, N-Gens and the Net Generation.Members of the generation have labeled themselvesas the Non-Nuclear Family generation, the NothingIs-Sacred Generation, the Wannabees, the Feel-GoodGeneration, Cyberkids, the Do-or-Die Generation,and the Searching-for-an-Identity Generation.This generation has been shaped by parentalexcesses, computers (Niemiec, 2000), and dramatictechnological advances. One of the most frequentlyreported characteristics of this generation is theircomfort with technology (Kersten, 2002). In general,Generation Y shares many of the characteristics ofXers. They are purported to value team work andcollective action (Zemke et al., 2000), embracediversity (The National Oceanographic andAtmospheric Office of Diversity, 2006), be optimistic(Kersten, 2002), and be adaptable to change (Jenkins,2007). Furthermore, they seek flexibility (Martin,2005), are independent, desire a more balancedlife (Crampton & Hodge, 2006), are multi-taskers(The National Oceanographic and AtmosphericOffice of Diversity, 2006), and are the most highlyeducated generation. They also value training (www.valueoptions.com). They have been characterized asdemanding (Martin, 2005), and as the most confidentgeneration (Glass, 2007). Like Xers, they are alsopurported to be entrepreneurial, and as being lessprocess focused (Crampton & Hodge, 2006).

Generational differences in the workplace5Possible generational differences and similaritiesAttitudes towards workThe perceived decline in work ethic is perhaps oneof the major contributors of generational conflictsin the workplace. Generation X for instance, hasbeen labeled the ‘slacker’ generation (Jenkins, 2007),and employers complain that younger workers areuncommitted to their jobs and work only the requiredhours and little more. Conversely, Boomers may beworkaholics and reportedly started the trend (TheNational Oceanographic and Atmospheric Officeof Diversity, 2006) while Traditionals have beencharacterized as the most hardworking generation(Jenkins, 2007). Indeed, the prevailing stereotype isthat younger workers do not work as hard as olderworkers do.Whether the younger generations do not work ashard as previous ones is debatable. A cross-sectionalcomparison of 27 to 40 year olds versus 41 to 65year olds in 1974 and 1999 indicated that both agegroups felt that it was less important that a workerfeel a sense of pride in one’s work in 1999 thanin 1974. In both age groups, work values amongmanagers declined between 1974 and 1999 (Smola &Sutton, 2002). Both age groups were also less likely in1999 to indicate that they believed that how a persondid his or her job was indicative of this individual’sworth. In 1999, both age groups were also less likelyto believe that work should be an important part oflife or working hard made one a better person (Smola& Sutton, 2002). Furthermore, older employees had aless idealized view of work than younger workers did.Indeed, it was postulated that after witnessing thelack of employer loyalty toward employees, the latterconsequently developed a less idealized view of work.Other sources of evidence do not support the claimthat there is a decline in work ethics among youngergenerations. For instance, Tang and Tzeng (1992)found that as age increased, reported work ethicdecreased, indicating that younger workers reportedhigher work ethics than older workers. Similarly,the 1998 General Social Survey, National OpinionResearch Center Survey indicated that 44% of thoseaged 18 to 24 indicated that they would chooseto spend more time at work, compared to 23% ofworkers of all ages (Mitchell, 2001), indicating thatmost younger workers were willing to try to workmore, more so than the average worker. However,these findings are not very recent. The possibility thatthe perceptions about the decline in work ethics isaccurate, but simply unsubstantiated by research dueto lack of research in the area therefore remains.Nevertheless, numerous factors beyondgenerational factors affect the work ethics ofemployees. For instance, work ethic varies witheducation level, whether a person works full-time orpart-time, income level and marital status. The lowerthe level of education of an employee, the highertheir work ethic has been found to be. People withfull-time jobs were found to be less likely to endorsea protestant work ethic than people with part-timejobs; and people with low incomes and those whowere married tended to report stronger protestantwork ethic (Tang and Tzeng, 1992).The perception of how hard one works mayalso be associated with how individuals themselvesapproach tasks as well. For instance, boomers haveoften been characterized as being process-oriented,while younger generations, as being results-focused,irrespective of where and when the task is done.While younger workers focus on high productivity,they may be happier with the flexibility of completinga task at their own pace and managing their owntime, as long as they get the job done right and bythe deadline. Current empirical evidence does notaddress this particular point however.

6Generational differences in the workplaceLoyalty towards the employerAnother point of contention among generationsregards loyalty towards employers. While Traditionalsand Boomers have been characterized as beingextremely loyal toward their employers, the lack ofloyalty of younger workers, especially Xers has beennoted. For instance, it has been postulated that Xersmay value their relationship with their co-workersabove the relationship with their company, especiallyif this co-worker is a friend (Karp, et al., 2002), andthat giving the employer two-weeks’ notice maybe an Xer’s idea of loyalty towards the employer(The National Oceanographic and AtmosphericAssociation Office of Diversity, 2006). In addition,Xers presumably view job-hopping as a valid careeradvancement method (Bova & Kroth, 2001).Xers presumably learned that loyalty to anemployer did not guarantee job security, fromwitnessing job losses among parents who were loyalto their employers and played by the rules (Karp etal., 2002). Xers more so than boomers have beenfound to report that remaining loyal to an employerwas outdated and were significantly less likely toreport being loyal to their employer (Kopfer, 2004).However, in that particular study, the Xers interviewedwere graduate students and the extent to which suchresults are applicable to non-graduate students is ofcourse debatable.Nevertheless, loyalty towards employers hasbeen found to decrease, depending on how ‘new’the generation was: the younger the generation,the least loyal the generation appeared to be. Forinstance, about 70% of traditionals reported thatthey would like to stay with their current organizationfor the rest of their working life compared with 65%of boomers, 40% of Xers, and 20% of Yers (Deal,2007). However, such a finding may make intuitivesense, given that humans tend to prefer the familiarand seek stability as they grow older. Consequently,they may be less desirous of going through theprocess of socializing into a new organization at alater stage in their lives. Smola and Sutton (2002)also found younger employees to be less loyal to theircompany and more ‘me’ oriented. They wanted to bepromoted more quickly than older workers, were lesslikely to feel that work should be an important partof their life and reported higher intention of quittingtheir job if they won a large amount of money.However, the perception of loyalty may be contextdependent (Deal, 2007). Firstly, compared with oldergenerations, Xers and Yers do not change jobs morefrequently than older people did at the same age.Furthermore, the frequency with which individualschange jobs may also be related to the economy, aspeople are more likely to change jobs if the economyis good and opportunities are numerous. Finally,younger workers typically hold several jobs while stillstudying, but tend to stabilize with one employer asthey get older. Therefore, loyalty (or lack of thereof)may be more a matter of age or other contextualcircumstances than a generational trait, according tofindings from Deal (2007).Although the extent to which employees feel loyaltowards their organizations appears to differ acrossgenerations, members of all generations reportedlyshare similar reasons for staying in their organization.In her book, Retiring the Generation Gap, whichprovides a wealth of information about generationaldifferences in the workforce, Deal (2007) reportedthat other factors likely to increase employees’ loyaltyincluded for instance, opportunities for advancementand promotions, opportunities to learn new skillsand develop a challenging job, as well as bettercompensation such as higher salaries or benefits.Employees were also more likely to stay if thecompany’s values matched their own. For instance,how a business handles organizational changeand manages itself as well as whether the businesscreates opportunities for a better quality of life,better communication, and improvements such asmore autonomy, control and greater contribution totheir specific job were cited as company values thatmattered. Individuals were also more likely to remainwith an organization if the organization respectedolder people with experience more than youngerpeople, and if organizations respected youngerpeople, at least for their talents (Deal, 2007).

Generational differences in the workplaceAttitudes regarding respect and authorityXers complain about managers who ignore ideasfrom employees, and ‘do-it because I said so’management (O’Bannon, 2001). While youngerworkers complain that there is a lack of respecttowards them in the workplace, older workersshare similar complaints, especially regarding theattitudes of younger and newer employees towardmanagement. Deal (2007) examined the attitudesof members of different generations relative toauthority finding that 13% of members of thetraditional generation included authority among theirtop 10 values, compared to 5% of boomers, 6% ofXers and 6% of Yers. This suggests that authoritymight be valued more by members of the traditionalgeneration than members of other generations.Although the percentages are small, they lend somesupport to the prevailing stereotypes that Traditionalsdisplay command-and-control leadership reminiscentof military operations and prefer hierarchicalorganizational structures (www.valueoptions.com).However, these figures do not support the claimthat Boomers presumably also prefer a top-downapproach to management. Most importantly, thesefigures indicate that the characteristics that are oftenattributed to a generation as a whole are oftenshared by only a small percentage of individualswithin that generation.The popular literature contains more informationabout how younger generations interact withauthority, as opposed to how they act when inposition of authority. For example, both Xers and Yersare comfortable with authority figures and are notimpressed with titles or intimidated by them. Theyfind it natural to interact with their superiors, unliketheir older counterparts and to ask questions. Yersin particular have been taught to ask questions, andquestioning from their perspective does not equatewith disrespect. Similarly, Yers believe that respectmust be earned and do not believe in unquestionablerespect. While there is not an empirical basisregarding the behaviors of Yers and Xers when inposition of authority, only a small percentage of theyounger generations feel a need to exert authority(Deal, 2007).7Younger workers like their older counterpartswant to be respected, although the understandingof respect among older and younger workers differs.Older workers want their opinions to be given moreweight because of their experience and for people todo what they are told, while younger workers wantto be listened to and have people pay attention towhat they have to say. Furthermore, older people maynot appreciate equal respect showed to all, and maywant to be treated with more respect than one wouldshow someone at a lower level in the hierarchy orwith less experience (Deal, 2007). Therefore, meetingthe expectations of respect that individuals hold maybe a genuine challenge in the workplace.Training styles and training needsGenerations have different preferred learning styles.The five preferred methods of learning ‘soft’ and‘hard’ skills, from Deal (2007), are summarized inTable 1. The majority of Xers and Yers prefer to learnboth hard skills and soft skills on the job, while themajority Traditionals and Boomers, prefer to learnsoft skills on the job, and learn hard skills throughclassroom instruction. Discussion groups was thesecond method of choice for learning soft skillsfor older workers, but was the fifth choice for Xersand the third choice for Yers. While Xers and Yersidentified getting assessment and feedback as a topfive method to learn soft skills, this was not the casefor older generations, lending some credence tothe stereotype that while older generations may besomewhat sensitive to feedback, younger generationsdesire it. By contrast, people in different generationshad similar top five methods for learning hard skills(Deal, 2007). While these methods are endorsed bya large proportion of the interviewees, individualpreferences among members of a generation varied.

8Generational differences in the workplaceTable 1. Generational differences in work related characteristics and expectationsWork ethicTraditionalsBaby BoomersGeneration XHard workingWorkaholicOnly work as hard asneededGeneration YAttitudes towards They valueauthority/rulesconformity,authority and rules,and a top-downmanagementapproach 13% includedauthority amongtheir top 10 values Some may still be They areuncomfortablecomfortable withinteracting withauthorities and areauthority figures 1not impressed withtitles or intimidated 5% includedby them 3authority among2their top 10 values They find it naturalto interact withtheir superiors 6% includedauthority in theirtop 10 values They believe thatrespect must beearned 4 6% includedauthority in theirtop 10 values 5Expectations Deferenceregarding respect 6 Special treatment More weight givento their opinions Deference Special Treatment More weight givento their opinions They want to beheld in esteem They want to belistened to They do not expectdeference They want to beheld in esteem They want to belistened to They do not expectdeferencePreferred way tolearn soft skills 7 On the job Discussion groups Peer interaction andfeedback Classroominstruction-live One-on-One jobcoaching On the job Discussion groups One-on-Onecoaching Classroominstruction-live Peer interaction andfeedback On the job One on Onecoaching Peer interaction andfeedback Assessment andfeedback Discussion groups On the job Peer interaction andfeedback Discussion groups One on coaching Assessment andfeedbackPreferred way tolearn hard skills Classroominstruction-live On the job Workbooks andmanuals Books and reading One-on-onecoaching/computerbased training Classroominstruction-live On the job Workbooks andmanuals Books and reading One-on-onecoaching On the job Classroominstruction-live Workbooks andmanuals Books and reading One-on-onecoaching On the job Classroominstruction-live Workbooks andmanuals Books and reading One-on-onecoachingFeedback andsupervisionAttitudes closer toboomers’May be insulted bycontinuous feedbackImmediate andcontinuousImmediate andcontinuous

Generational differences in the workplaceTable 1. Generational differences in work related characteristics and expectationsAttitudesregarding loyaltyto their employerTraditionalsBaby BoomersGeneration XGeneration Y Considered amongthe most loyalworkers 8 About 70% ofthose interviewedwould like tostay with theirorganization forthe rest of theirworking life9 They valuecompanycommitment andloyalty10 About 65% ofthose interviewedwould like tostay with theirorganization forthe rest of theirworking life11 Less loyal tocompaniesthan previousgenerations butloyal to people12 About 40% ofthose interviewedwould like tostay with theirorganization forthe rest of theirworking life13 Committedand loyal whendedicated to anidea, cause orproduct14 About 20% ofthose interviewedwould like tostay with theirorganization forthe rest of theirworking life15Sacrificed personallife for workValue work/lifebalanceValue work/lifebalance?Work/life balancePerceivedelements ofsuccess in theworkplace16 Meet deadlines(84%) Willingness to learnnew things (84%) Get along withpeople (81%) Use computers(78%) Speak clearly andconcisely (78%) Use computers(82%) Willingness to learnnew things (80%) Get along withpeople (78%) Meet deadlines(77%) Organizational skills(73%) Use computers(79%) Meet deadlines(75%) Willingness to learnnew things (74%) Speak clearly andconcisely (72%) Get along withpeople (71%) Use computers(66%) Meet deadlines(62%) Multitasking (59%) Willingness to learnnew things (58%) Speak clearly andconcisely (55%)Topdevelopmentalareas 17 Skills training in myareas of expertise Computer training Team building Skills training in myareas of expertise Leadership Computer training Leadership Skills training in myareas of expertise Team Building Leadership Problem solving,decision making Skills training in myareas of expertisePreferredleadershipattributes 18 Credible (65%) Listens well (59%) Trusted (59%) Credible (74%) Trusted (61%) Farsighted (57%) Credible (71%) Trusted (58%) Farsighted (54%) Listens well (68%) Dependable (66%) Dedicated (63%)9

10Generati

the baby bust generation, because of its small size relative to the generation that preceded it, the Baby Boom generation. The term Generation X spread into popular parlance following the publication of Douglas Coupland's book about a generation of individuals who would come of age at the end of the 20th century.