Transcription

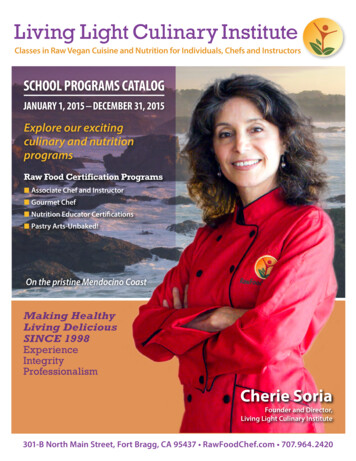

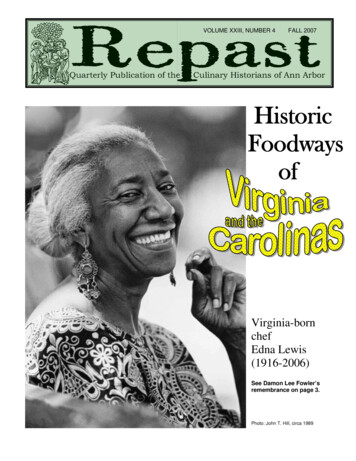

VOLUMENUMBER4 4 FALL20002007VOLUMEXVI,XXIII,NUMBERFALLQuarterly Publication of theCulinary Historians of Ann ArborHistoricFoodwaysofVirginia-bornchefEdna Lewis(1916-2006)See Damon Lee Fowler’sremembrance on page 3.Photo: John T. Hill, circa 1989

REPASTVOLUME XXIII, NUMBER 4FALL 2007HCURDLED WITHGIZZARD SKINow does a European culinary technique become a staple inan élite American kitchen of the Early Federal period?In the undated manuscript cookbook written by VirginiaJefferson Randolph Trist, she included five dessert recipes sheattributed to James Hemings, slave and chef to Thomas Jefferson inParis. One unusual recipe is for Chocolate Crème (with thevariations of Tea Creams and Coffee Creams), calling as it does forthe cook to “put 3 gizzards in the napkin [in a bowl] and pass thecream through it four times as quick as possible, one person rubbingthe gizzards with a spoon while another pours.” The final part of therecipe reads, “The gizzards used for this purpose are only the insideskins taken off as soon as the chicken is killed, washed, dried, andkept in paper bags in a dry place. The effect is the same with rennet.James.”A RECIPE FROM JAMESHEMINGS AT MONTICELLOby Leni A. SorensenCHAA member Leni Ashmore Sorensen of Crozet, VA is anAfrican-American Research Historian at the Monticello estatenear Charlottesville. In 1999, she was the historical technicalconsultant for the CBS miniseries “The Memoirs of SallyHemings”. In December 2005 she completed a Ph.D. at theCollege of William and Mary, with a dissertation on fugitiveslaves in Richmond, 1834-44. Dr. Sorensen’s recent writingand current research have focused on foodways and gardenways in African and African-American history. On October15, she gave a lecture before the Peacock-Harper CulinaryHistory Friends Group (Blacksburg, VA), “Straddling TwoWorlds: In Jefferson’s Kitchen at Monticello”, anddemonstrated the preparation of one of Jefferson’s favoritedishes, lemon curd. Her previous article for Repast was“Taking Care of Themselves: Food Production by theEnslaved Community at Monticello” (Spring 2005).Virginia had been born the same year James Hemings died,1801, and even her elder sisters had been very little girls that year.By the 1810’s, when the young white women began to take theirturns opening the locked doors to dole out the stored foodstuffs, itwas the enslaved sisters-in-law Edith Fossett and Frances Hern whocooked for the table at Monticello.Within a week of reading the recipe for gizzard rennet I wasscheduled to butcher 20 fryers, and of course I had to try preparingthe gizzards in this way. The cleaning process was verystraightforward, but my curiosity concerned how quickly themembrane that lines the gizzard would take to dry. Late Spring andSummer in Virginia are hot and often full of flies. Surely a dryingprocess that took too long would be distasteful.To my surprise, within 15 minutes of being stripped out of themuscular gizzard and rinsed of its gritty contents the mustardyellow membrane was as dry as a potato chip! A paper bag wouldbe a perfect storage place and at Monticello chickens were beingbutchered regularly for the dining table.ISSN 1552-8863After a mad scramble to find references to this unusual (to me)source of rennet, my questions became “Where did James learn it?”and “How did this recipe get handed down?” Question number onewill have to wait for more research, but question number two mayhave some answers. Before the death of Thomas Jefferson in 1826,his granddaughters Anne, Ellen, Cornelia, Virginia, Mary, andSeptimia rotated duties keeping the keys in the kitchen atMonticello. The cooks during most of their lives would have been,first, Peter Hemings, and later Edith Hern Fossett and FrancesGillette Hern. All three cooks were related to and learned significantparts of their craft from James Hemings. Fossett and Hern werelittle girls during the years 1793 to early 1796, when James taughthis brother Peter the “art of cookery”, but both girls may well havebeen the sculleries under Peter after that and until they both weretaken to the President’s house.Published quarterly by theCulinary Historians of Ann Arbor tor . . . Randy K. SchwartzCHAA President . . Carroll ThomsonCHAA Program Chair . . Julie LewisCHAA Treasurer . . Dan LongoneCHAA Founder and Honorary President Jan LongoneThe material contained in this publication is copyrighted.Passages may be copied or quoted provided that the source is credited.At the President’s house, Edith and Frances served and trainedunder the French chef Honoré Julian and all were supervised by theFrench maître d’hôtel Etienne Lamaire. I currently surmise that theoriginal recipe for gizzard rennet came into the Monticello kitchenvia James Hemings and was used there beginning in 1793. It wasthere that Edith and Frances first learned it. Then while working inWashington the young women may well have had the techniquereinforced. Later, as the Randolph girls began to write their varioushousekeeping/cookery books, they could have turned to Peter orEdith or Frances to learn the details of the often-used recipe andheard that the original had come from James Hemings so long ago.Subscriptions are 15/year (send a check or moneyorder, made out to CHAA, to the address below).For information about memberships, subscriptions,or anything in this newsletter, contact:Randy K. Schwartz1044 Greenhills DriveAnn Arbor, MI 48105-2722tel. 734-662-5040Rschw45251@aol.com2

REPASTVOLUME XXIII, NUMBER 4FALL 2007EDNA LEWIS, SOUTHERNCULINARY GIANT, LEAVES ALEGACY AS LOVELY AS SHE WASby Damon Lee FowlerDamon Lee Fowler of Savannah, GA is a food writer, aculinary historian, and a member of the Southern FoodwaysAlliance. He is the author of six cookbooks, includingClassical Southern Cooking: A Celebration of the Cuisine ofthe Old South (New York: Crown Publishers, 1995), and theeditor of Dining at Monticello: In Good Taste and Abundance (Charlottesville, VA: Thomas Jefferson Foundation,Inc., 2005).On February 13, 2006, food lovers mourned the passing of agiant in American, and especially Southern, gastronomy.Edna Lewis, a gentle soul with the mind and heart of a poet, diedquietly at home, just two months shy of her 90th birthday.and, when her health began failing, her caregiver. Together theypublished her last major work, The Gift of Southern Cooking, andtoday Peacock continues her legacy in the kitchen of Watershed,his restaurant in Decatur, GA.She was a lovely, graceful woman, possessed of a dazzlingsmile, dancing dark eyes, and skin like warm chocolate. With herthick, snow-white hair elegantly knotted at the nape of her neck,her signature dangling earrings, and African print dresses of herown design, she cut a striking figure.Though Miss Lewis had long since retired by the time of herdeath, her lovely cooking remains more than a mere memory. Herlegacy includes three earlier cookbooks, including The Taste ofCountry Cooking, a kind of memoir in recipes that preserved arapidly vanishing way of life and cooking, which is to this daywidely acknowledged a modern classic.But it is not her physical beauty that made Edna Lewismemorable. This brilliant, largely self-taught woman was, quitesimply, one of the great culinary minds of the 20th Century.In fact, it has been more through her writing than herprofessional cooking that she brought Americans home to our rootsand taught us to respect simple elegance in a world whererestaurant cooking was becoming increasingly overwrought andpretentious, if not downright silly.Born 1916 in Freetown, VA, a now defunct communityfounded in the 1840’s by freed slaves, Miss Lewis grew up withthe flavors of fresh, naturally raised food. They grew all their ownvegetables, raised and slaughtered their own cattle, hogs, andpoultry, and hunted and foraged for game and wild fruits andvegetables. The way that these prime ingredients were cooked wassimple, and yet it was elegant in ways that more sophisticatedcuisines could never match.Though we were destined never to meet face to face, MissLewis had a special place in my own life and work. The Taste ofCountry Cooking had had a profound effect on me while I wasworking on my own first cookbook, and we struck up acorrespondence.Throughout a career that spanned more than five decades, shechampioned the fresh, natural ingredients of her childhood longbefore it was fashionable to do so, and her cooking was marked bythe same clean simple flavors.She was quiet, retiring, a bit shy, but generous in spirit, warm,funny, charming, and wise. As our mutual passion for goodcooking grew, our friendship grew as well, the old-fashioned way.We wrote real letters, not e-mails, and shared many long telephonecalls. The quiet, musical sound of her voice is still bright in mymemory.She defied fashion and did not believe in being contrived orfussy with food. Her philosophy was as exquisitely simple as hercooking. She believed that if one took the time to find the bestingredients, and respected and handled them with care andrestraint, the results would always be good.Unhappily, our friendship bloomed just as her health andmemory were beginning to fail, but the impression that short,precious time left on my writing and cooking— and on my soul— isdeep, and I am grateful to have known her at all.She fed countless celebrities and world leaders from NewYork to Middleton Place in Charleston, SC, her culinary prowesshas been celebrated by every major American food magazine, shehas been awarded such prestigious honors as Grande Dame by LesDames d’Escoffier International, and still her cooking remainedforthrightly, unapologetically simple, never straying far from therich heritage of her rural Southern roots.The Edna Lewis Reader In 1988, Miss Lewis met a young chef named ScottPeacock, who quickly became a protégé, professional partner,3The Edna Lewis Cook Book, with EvangelinePeterson (Ecco Press, 1976)The Taste of Country Cooking (Knopf, 1978)In Pursuit of Flavor (Knopf, 1988)The Gift of Southern Cooking, with ChefScott Peacock (Knopf, 2003)

REPASTVOLUME XXIII, NUMBER 4FALL 2007was known about Mrs. Abby Fisher. The Hess notes, however,revealed some basic biographical information. First, Karen Hessreviewed important data from the 1880 Federal Census taken inSan Francisco.5 In this census, it was reported that Abby Fisherwas 48 years old and born in South Carolina. She stated that herfather was born in France and her mother was born in SouthCarolina. The census taker recorded Abby’s “color” as “Mu” formulatto. From these data, Karen Hess proposed that Abby Fisherwas born a slave in South Carolina; her father, most likely, was awhite plantation owner and her mother, a Black slave.SOLVING A CULINARYHISTORY MYSTERYTRACING ABBY FISHER’SROOTS TO SOUTH CAROLINAby Robert W. BrowerSecond, Abby was married to Alexander C. Fisher and, at thetime of the census, they had four children living with them in SanFrancisco. The three oldest children, ages 16, 12, and 10, wereborn in Alabama, but the youngest child, age 3, was born inMissouri. Based on these data and a comment in the Preface andApology in the cookbook, Karen Hess correctly concluded thatthe Fishers were living in Mobile, Alabama in 1870. Shesurmised that their youngest child was born in Missouri while theFishers were on “the terrible trek from Alabama to California.”Robert Brower is an attorney and independent culinaryhistorian in El Sobrante, CA. His writings include severalarticles in The Oxford Encyclopedia of Food and Drink inAmerica, and the Introduction to a reprint edition of AntoniaIsola’s Simple Italian Cookery (Applewood Books, 2005).Robert traveled to Ann Arbor to participate in the BiennialSymposia on American Culinary History in 2005 and 2007.Printed in San Francisco by the Women’s Co-operativePrinting Office in 1881 and self-published by Mrs. AbbyFisher1, What Mrs. Fisher Knows About Old Southern Cooking isbelieved to be one of only four 19th-Century Black-authoredAmerican culinary works.2Finally, based upon San Francisco city directories from 1880,1881, and 1882, Karen Hess noted that Abby Fisher hadindependently established her own San Francisco companymanufacturing pickles and preserves. This business enterprise,which was created by a woman who could not read or write, wascomplemented by the improbable publication of the cookbook of160 of her remembered recipes. As Hess correctly observed, Mrs.Fisher was “a remarkably resourceful woman.”The book is scarce, since most copies were destroyed in thefire following the 1906 San Francisco earthquake. Two scannedoriginals of the cookbook can be found online.3 ApplewoodBooks published a facsimile edition in 1995, with valuablesupplemental historical notes by Karen Hess.4Because her reconstruction of Abby Fisher’s life was based onvery limited data, Hess’s notes raised significant and interestingquestions about Fisher’s biography and the source of her culinaryexpertise.6 This article is an attempt to answer one of thosequestions by expanding the Hess biographical notes to trace AbbyFisher’s roots to South Carolina.7The Historical Notes by Karen HessBefore the publication of the Hess notes in 1995, very littleAdditional Biographical InformationAuthor’s note: An earlier version of this article was presented at ameeting of the Culinary Historians of Northern California. I wish toacknowledge their questions and comments, which have greatlyimproved this work. In addition, this article would not have beencomplete without the courteous and professional assistance of the staff atthe South Carolina Department of Archives and History in Columbia.1The Women’s Co-operative Printing Office was a commercial printshop located on Montgomery Street in San Francisco serving the legaland business community of the San Francisco Bay Area. The shopspecialized in printing appellate briefs, corporate reports, and businessforms. Although it printed some books, it was not a publisher. RogerLevenson, Women in Printing: Northern California, 1857-1890 (SantaBarbara: Capra Press, 1994).2Jan Longone, “Early Black-Authored American Cookbooks”,Gastronomica, Vol. 1, No. 1 (Winter 2001), pp. 96-99.3One scanned original is part of the Feeding America project sponsoredby the Michigan State University Library and MSU ks/html/books/book 35.cfm). Ascan of another original copy, this one from the cookbook collection atthe Bioscience and Natural Resource Library at the University ofCalifornia at Berkeley, can be found in the cookery collection accessibleon the American Libraries page of the Internet erkno00fishrich). The latterscanned copy is fully searchable in a flipbook format.4Mrs. Abby Fisher, What Mrs. Fisher Knows About Old SouthernCooking, Soups, Pickles, Preserves, Etc. Facsimile edition, withHistorical Notes by Karen Hess (Bedford, MA: Applewood Books,1995).My investigation started with an expanded review of therelevant census reports. These include the 1830, 1840, 1850, and1860 Federal Census of South Carolina, the 1860 and 1870Federal Census of Alabama, the 1866 State Census of Mobile,Alabama, and the 1880, 1900, 1910, 1920, and 1930 FederalCensus of San Francisco, California.8Some of this information about Abby Fisher has beenpublished elsewhere. For example, data from the 1870 Federal5U.S. Census, San Francisco, Page No. 9, Supervisor District No. 1,Enumeration Dist. No. 65, June 4, 1880.6Rafia Zafar, “What Mrs. Fisher Knows About Old Southern Cooking”,Gastronomica, Vol. 1, No. 4 (Fall 2001), pp. 88-90.7In addition to the Hess notes, there is a very sympathetic and movingcommentary on Abby Fisher’s life, and the culinary significance of hercookbook and recipes, in Laura Schenone, A Thousand Years Over a HotStove: A History of American Women Told Through Food, Recipes, andRemembrances (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 2003), pp.82-85.8It would have been helpful to see the 1890 Federal Census for SanFrancisco, but the bulk of the 1890 United States Census records weredestroyed in a fire.4

REPASTVOLUME XXIII, NUMBER 4FALL 2007Census of Mobile and the 1900 Federal Census of San Franciscoformed the basis of a thoughtful and expanded short biographicalsketch written by Alice Arndt and published by her in 2006.9Using the 1900 Federal Census data from San Francisco andadditional research assistance provided by the staffs of theMichigan State University Library, the Schlesinger Library atRadcliffe, the Mechanics’ Institute Library in San Francisco, andthe African-American Museum and Library in Oakland, CA, aquasi-factual “story” of Abby Fisher’s life was included in TriciaMartineau Wagner’s 2007 book, African American Women of theOld West.10This James Andrews appears in the 1830, 1840, 1850, and1860 Federal Census. Although the amount of data in each censusvaries slightly, on the whole, it is consistent.These two recent publications do not, however, revealanything about Abby Fisher’s roots in South Carolina. Theyprove, by implication, that these roots cannot be traced withcensus data alone. Although experts in genealogical researchgenerally agree that uncorroborated census information may bevery unreliable11, as is the case with some of the census data forAbby Fisher and her family, the central problem with tracingAbby Fisher’s roots prior to 1865 is the absence of a single pieceof data to connect Abby Fisher to antebellum South Carolina.In the 1850 Federal Census, there is additional information.James J. Andrews is listed as a 48-year-old “planter” living in thearea “between Santee and Edisto, north of Belville Road”,Orangeburg, South Carolina.16 The value of his real estate isstated as 75,000. Andrews’s wife, Ann, his two sons, James H.and Edward, two overseers, and a carpenter are noted. Theaccompanying Slave Schedule lists individuals by sex and age.There were 70 slaves, 34 male and 36 female.17In the 1830 census for Orange Parish15, James J. Andrews wasrecorded as the head of a family. The “family” included 2 freewhite males and 4 free white females. Andrews owned 15 maleand 22 female slaves. In 1840, also for Orange Parish, James J.Andrews appears as “J.J. Andrews.” There were 48 people at hisproperty: 4 white males, 4 white females, and 40 slaves. Thecensus stated that 23 of these people were involved in agriculture.The 1860 Federal Census data are similar. James J. Andrewsis listed as a 58-year-old “farmer” living in the “OrangeburgDistrict”. The value of his real estate is 40,000 with anadditional personal estate of 90,000. Andrews’s wife, Ann, hisson, Edward, and one overseer are noted. The accompanyingSlave Schedule lists 66 slaves, 35 male and 31 female.18 Thisschedule also states there were 14 slave houses.This lack of information about Abby Fisher is not unusual.Since information about slaves as African-American persons wasnot considered important, the census takers only reported on thename of the slave owner and the gender and age of every slave heowned. There are very few names or identities of slaves in anycensus before 1865.The absence of any connection of Abby Fisher to SouthCarolina in the state and federal census records inspired acomplete search of all public records in San Francisco to look fora clue. This search yielded various property deeds, deathcertificates, probate files and cemetery records.12 These recordsrevealed one potentially important fact connecting Abby Fisher toantebellum South Carolina: Abby Fisher’s father’s name wasJames Andrews.13Ironically, this type of biographical research, which yieldsimportant factual background about Abby Fisher, has been called“historical trivia” when compared with “insights” gleaned fromcontinued on next pageAbby’s reported birth date, June 1831, and a presumed marriage date of1859. I omitted from the filter the information, stated by Abby Fisher,that her father was born in France. According to the African-Americanresearch expert at the LDS Family History Center in Oakland, CA, whereI carried out this search, such a claim would have been completelyunreliable. This expert noted that many people in the middle country nearthe Santee River spoke French because that area had been settled bynumerous French Huguenot immigrants, and Abby, like other slaves,might have assumed that her father was born in France merely becausehe spoke French.15The names “Orange”, “Orangeburgh”, and “Orangeburg” areconfusing. Over time, the names have been used for different places: thecity, the parish, the district, and the county.16This reported location is too general to specifically identify thelocation of Andrews’s property. However, a plat map of an adjacentproperty reveals that Andrews’s property was 7 miles northwest of theCity of Orangeburg between Limestone Creek and the road fromOrangeburg to Columbia.17In 1854, Harriet Beecher Stowe published The Key to Uncle Tom’sCabin, which was her personal research documenting the depiction ofinhumane treatment of slaves in her serial, Uncle Tom’s Cabin. One itemthat she cites is an Orangeburg newspaper ad placed in 1852 by J. J.Andrews offering a 25 reward for one of his slaves, a runaway.18Significantly, none of the female slaves were reported as 28 or 29years old (although four were reported as 30 years old). This is consistentwith what we know about Abby Fisher: based on other information, bothTricia Wagner and I had already surmised that Abby’s marriage occurredin 1859, and that Abby had left the Andrews farm and gone to live withAlexander Fisher in Mobile, AL prior to the 1860 census of SouthCarolina. Given her reported birth date of June 1831, she would havebeen 28 or 29 years old at the time of that census.James J. Andrews of Orangeburg, SCUsing the name, James Andrews, and a tiered fact filter for the1830, 1840, 1850 and 1860 Federal Census of South Carolina,only one James Andrews qualified as Abby Fisher’s father: JamesJ. Andrews, a farmer with 2,000 acres of farmland located nearOrangeburg, SC.149Alice Arndt, ed., Culinary Biographies (Houston: Yes Press, Inc.,2006), pp. 162-163.10Tricia Martineau Wagner, African American Women of the Old West(Guilford, CT: Twodot - The Globe Pequot Press, 2007).11Richard H. Steckel, “The Quality of Census Data for HistoricalInquiry: A Research Agenda”, Social Science History, Vol. 15, No. 4(Winter 1991), pp. 579-599.12Abby Fisher is buried in an unmarked grave at Cypress LawnCemetery in Colma, California.13The San Francisco public records also reveal that Abby Fisher’smother was Abbie Clifton and that Abby’s maiden name was also AbbieClifton. The latter maiden name was independently confirmed by aSeptember 28, 1869 deposit receipt from the Mobile, AL branch of theFreedman Savings and Trust.14The tiered fact filter included: (1) name; (2) age; (3) occupation, i.e.,farmer; (4) size of farm; (5) owner of a female slave under 10 years oldfor the 1840 federal census; (6) owner of an 18-year-old female slave forthe 1850 federal census; and (7) no 28-year-old female slave reported inthe 1860 federal census. The last three tiers of the filter were based upon5

REPASTVOLUME XXIII, NUMBER 4FALL 2007The first region, the Coast Region, is land at, or just above, sealevel.23 This region includes the Sea Islands, certain salt marshes,and the southern portion of the State’s shoreline. The commercialcrop of the Coast region was long-staple cotton. Orange andlemon trees were common. The Lower Pine Belt, or Savannah, isthe second region, paralleling the Coast Region; it is low and flatwith a maximum elevation of 134 feet above sea level. Some ofthis land is subject to the influence of the tide, while otherportions, depending on elevation, are completely above tidewater.Rice was the commercial crop of this region.ABBY FISHERcontinued from page 5the recipes themselves.19 (We will turn to those recipes furtherbelow.)James J. Andrews was an important and influential citizen ofOrangeburg County. In 1831, he was one of 40 “sundryinhabitants of the village and immediate neighbourhood ofOrangeburgh” who signed a petition asking the South CarolinaSenate and House of Representatives to incorporate the village ofOrangeburgh as a city. James Andrews also served as aCommissioner for Roads and as a Commissioner of PublicBuildings for Orange Parish.20Orangeburg lies in the third region, the Upper Pine Belt, orCentral Cotton Belt. This region, which irregularly parallels andinterlaces with the Lower Pine Belt, has an elevation of 130-250feet. In the Upper Pine Belt, there was sufficient water flow inrivers and most creeks to support mills. There were, however,some large inland swamps adjacent to these rivers, and smallerswamps near creeks and streams. Crops in this region includedcotton, corn, rice, sweet potatoes, oats, rye, and wheat. Fish wasabundant.James J. Andrews died on September 9, 1863. His will wasadmitted to probate at the Court of Ordinary in Orangeburg.Nearly all of the records in the Ordinary’s Office were destroyedby fire in February 1865, when General Sherman and his troopsmarched through Orangeburg and burned the town to theground.21The Culinary Landscape of South CarolinaThe Red Hills are fourth. Named for their red clay soils, thesehills have an elevation of 300-600 feet and a much drier climate.The staple crops were cotton and a variety of grains. The fifthregion is the chain of Sand Hills that abut the Red Hills at ahigher elevation, 600-700 feet. Because of its soil, this region issometimes called the Pine Barrens. Notwithstanding its drearytitle, the region had a rich commercial agricultural production ofcotton, corn, grains, vegetables, and fruits.Confirmation that Abby Fisher’s roots lie in Orangeburg, SCcan be found in the ingredients used in Abby Fisher’s recipes, inthe crops and animals raised on James Andrews’s farm inOrangeburg, and by a comparison of Abby Fisher’s recipes withthose found in a contemporaneous cookbook from a nearbyplantation. Although this determination will necessarily be basedon circumstantial evidence, the essential background informationis simple and straightforward.The Piedmont (“foot of the mountains”) is the sixth region. Itstarts the back country of South Carolina. With an elevation of400-800 feet, it was suitable for cotton, grains, and grasses forlivestock and dairy animals. The seventh and last region is theAlpine (mountain) region in the northwest corner of the state,with an elevation of 900-3,430 feet.Historically, South Carolina has been divided into seven welldefined regions. From the coast to the mountains, they are: theCoast Region, the Lower Pine Belt (or Savannah Region), theUpper Pine Belt, the Red Hills Region, the Sand Hills Region, thePiedmont Region, and the Alpine Region. These regions areprimarily defined by elevation, soils, and climate.22For ease of analysis of its culinary landscape24, South Carolinacan be divided into three distinct zones: the low country, themiddle country, and the up country. The low country includes theCoast Region and the Lower Pine Belt. The low country wasgenerally a low, flat, and level coastal plain with malaria-infestedcypress swamps and a large slave-driven rice plantation economy.The climate is sub-tropical. The zone is narrow; together, bothregions are about 50 miles wide.25 The middle country, whichincludes the Upper Pine Belt and the Red and Sand Hills, is at a19Sara Roahen, “What Abby Fisher Knows”, Tin House magazine, Vol.4, No. 2 (2003), republished in Lolis Eric Elie, Cornbread Nation 2: TheUnited States of Barbecue (Chapel Hill, NC: University of NorthCarolina Press, 2004), pp. 220-222.20Daniel Marchant Culler, Orangeburgh District, 1768-1868: Historyand Records (Spartanburg, SC: The Reprint Company, 1995).21The Andrews will was folded. The fire charred and destroyed portionsof the folds, although paper that was protected inside the folds survived.The readable parts of the will are, unfortunately, inconclusive concerningAbby Fisher’s relationship to James J. Andrews.22Robert Mills, an engineer and architect, first enumerated these sevenregions in his Atlas of the State of South Carolina, Made Under theAuthority of the Legislature; Prefaced with a Geographical, Statisticaland Historical Map of the State (Baltimore: F. Lucas, 1825). Heclassified the geographical “face” of the state as follows: the Sea Islands,the tide swamps, the inland rice swamps (a belt about 50 miles wide), thesand hill region, an unnamed red clay belt, the foot of the mountains(piedmont), and the mountains. This seven-part division of SouthCarolina was still recognized as valid after the turn of the century; seeEbbie Julian Watson, Handbook of South Carolina; Resources,Institutions and Industries of the State; a Summary of the Statistics ofAgriculture, Manufactures, Geography, Climate, Geology andPhysiography, Minerals and Mining, Education, Transportation,Commerce, Government, Etc, Etc., Second Ed. (Columbia, SC: The StateCompany, 1908), pp. 66-68.23The following details about the regions are based on M. B. Hillyard,The New South: A Description of the Southern States, Noting Each StateSeparately, and Giving Their Distinctive Features and Most SalientCharacteristics (Baltimore: The Manufacturers’ Record Co., 1887), pp.143-155.24Landscape means “land shaped by human hands”. Mart A. Stewart,“What Nature Suffers to Groe”: Life, Labor, and Landscape on theGeorgia Coast, 1680-1920 (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press,1996), pp. 11-12.25In his cookbook, Hoppin’ John’s Lowcountry Cooking: Recipes andRuminations from Charleston and the Carolina Coastal Plain (NewYork: Bantam Books, 1992), John Martin Taylor states that the lowcountry extends from the coast “inland about eighty miles to the FallLine” (p. 3). It is historically erroneous to expand the low country to theFall Line. This division overly simplifies South Carolina’s culinarylandscape into l

Isola's Simple Italian Cookery (Applewood Books, 2005). Robert traveled to Ann Arbor to participate in the Biennial Symposia on American Culinary History in 2005 and 2007. rinted in San Francisco by the Women's Co-operative Printing Office in 1881 and self-published by Mrs. Abby Fisher1, What Mrs. Fisher Knows About Old Southern Cooking is