Transcription

REPRODUCTIVE HEALTHFORHealth Science StudentsLecture NoteFeleke Worku (MD)Samuel Gebresilassie (MD)University of Gondar

REPRODUCTIVE HEALTHForHealth Science StudentsLecture NoteFeleke Worku (MD) LecturerSamuel Gebresilassie (MD)Associate Professor of Gynecology andObstetrics2008In collaboration withThe Carter Canter (EPHTI) and The FederalDemocratic Republic of Ethiopia Ministry ofEducation and Ministry of HealthUniversity of Gondar

PREFACEThis lecture note lecture note in reproductive health for healthscience students is prepared in accordance with the currentcurriculum, which we think will be of help to meet themillennium development goals in the health perspective,which is broader in scope and extensive in contents than thealready existing maternal on child health. It will help studentsand other readers to understand the current reproductivehealth understandings.Starting with the definition, we have gone through itscomponents. Each component was dealt with extensively as achapter. Emphasis was given to the service provision andchallenges and on how to overcome the challenges whichmost of the time is not easily available and accessible for thestudents. In each reproductive health component, we tried toaddress important national and international up-dated figuresand evidence based and practical reproductive health andrelated issues.The authorsi

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTWe would like to express our deepest gratitude to The CarterCenter, Ethiopian Public Health Training Initiative to take theinitiative and sponsor the development of this lecture note. Wewould like to thank the internal reviewers of the University ofGondar staff, W/t Alemtsehay Mekonnen from the Departmentof Midwifery and Dr. Desalegn Tigabu, Department ofepidemiology.We would like to express our appreciation to the externalreviewers: ACCESS JHPIEGO for the excellent commentsthey gave us.We would like to thank the reviewers of inter institution:Dr. NegaJimma UniversityDr. MillionDebub UniversityAto ArayaMekelle UniversityAto AntenehHaremaya UniversityFinally, we thank all individuals and institutions who helped usin making this invaluable material to come to a reality.ii

Table of contentPreface.iAcknowledgement.iiTable of Content . iiiList of Table. viiList of Figures. viiiCHAPRTER 1: Introduction to Reproductive Health. 11.2.Definition and introduction. 11.1.Historical development of the concept . 21.2.Development of Reproductive Health . 81.3.Magnitude of Reproductive Health Problem . 101.4.Components of Reproductive Health . 12Reproductive health indicators . 132.1. CRITERIA FOR SELECTING INDICATORS. 142.2. Sources of data . 182.3. Reproductive Health Indicators for GlobalMonitoring. 193.Gender and Reproductive Health. 243.1. Gender differences: . 294.REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH AND DEFINING TARGETPOPULATION . 34CHAPRTER 2: Material Health . 401.Introduction . 40iii

2.The Safe Motherhood Initiative . 422.1. Essential Services for Safe Motherhood. 432.2. Causes of Maternal Mortality and Morbidity . 492.3 Maternal health services . 612.4.Estimation of maternal mortality. 91CHAPRTER 3: Abortion . 1083.1. Public Health Importance of Abortion . 1103.2. Why Women Find Themselves with UnwantedPregnancy? . 1133.3 Why does induced Abortion Occur? . 1153.4 Legislation and policies. 1183.5Inadequate services . 1193.6What can be done about unwanted pregnanciesand unsafe abortions?. 1203.7Grounds on Which Abortion is Permitted, revisedabortion law of Ethiopia, (House of Parliament,2005) . 125CHAPRTER 4: Family Planning . 1274.1.Origins and Rationale for Family PlanningPrograms in Developing Countries . 1294.2.Family Planning methods . 1334.3.Fertility Trends and Contraceptive Use. 1354.4.Men’s Attitude towards FP . 138iv

4.5.Fertility among Different Groups . 1384.6.Counseling in Family Planning. 1394.7.Trends in Contraceptive Use in Ethiopia. 1444.8.Family Planning Delivery Strategies . 1454.9.Reasons for Not Using Contraceptives . 148CHAPRTER 5: Sexually Transmitted infections . 1515.1Introduction. 1515.2Classification of STIs. 1585.3Traditional Approaches to STI Diagnosis. 1605.4The STI Syndromes and the SyndromicApproach to Case Management . 1615.5Why Invest in STI Prevention and Control Now? .1655.5. STI Control Strategies. 1665.6Obstacles to Provision of Services for STIControl . 169CHAPRTER 6: HIVIDS and Reproductive Health . 1736.1.Introduction. 1736.2.Modes of Transmission of HIV . 179CHAPRTER 7: Harmful Traditional Practices . 2197.1. Introduction . 2197.2. Violence against Women . 2227.3. Female genital mutilation (FGM). 2367.4. Early Marriage (EM): . 239v

CHAPRTER 8: Adolescent Reproductive Health. 2468.1.Global Youth Today. 2488.2.Reproductive Health Risks and consequencesfor adolescents . 2568.3Causes for early unprotected sexual intercoursein adolescents . 2688.4Effects of gender roles . 2698.5Adolescents’ contraceptive use. 2708.6Adolescent Reproductive Health Services . 271CHAPRTER 9: Child Health. 2849.1. Introduction . 2859.2. The objectives of child survival and child healthof ICPD are:. 2889.3. Diarrhoeal Diseases. 2939.4. Respiratory Infections . 3199.5. Vaccine Preventable Diseases . 3299.6. The Expanded Program Of Immunization . 3689.7. Growth Monitoring. 393vi

List of TableTable .1 Women's Lifetime Risk of Death fromPregnancy, 2000 . 50Table .2 Global ‘Summary of the HIV. AIDS Epidemic,December 2007. 107Table 3 Global Summary of the HIV/AIDS Epidemic,December 2007. 177Table 4 describes the rateof Mother-to- child Transmissionin the absence of intervenition . 184Table 5 Effects of social environment on adolescent RHbehavior . 254Table 6 Unsafe abortion: Regional Estimates of Mortalityand Risk of Death. 260Table 7 Tetanus Toxoid Immunization for Women . 347vii

List of FiguresFigure 1: A Conceptual Framework for Monitoring andEvaluating Reproductive Health ProgrammeComponents. 17Figure 2: The Life Cycle approach in Women's andMen's Health: . 32Figure 3: The reproductive life cycle . 33Figure 4: The Life Cycle of Violence Against Womenand its Effects on Health*. 227Figure 5: Distribution of 10.5 million deaths amongchildren less than 5 years old in alldeveloping countries, 1999. 291Figure 6: Proportion of Global Burden of SelectedDiseases Borne by Children Under 5 Years(Estimated, Year 2000)*. 292viii

Reproductive HealthCHAPTER 1INTRODUCTION TOREPRODUCTIVE HEALTHLearning objectives: To define reproductive health To know the historical development of RH Understand magnitude of RH problems Understand RH indicators and criteria forselection of indicators Tounderstandtherelationshipofreproductive health and gender Know the targets of reproductive health1. Definition and introductionReproductive health is defined as” A state of completephysical, mental, and social well being and not merelythe absence of disease or infirmity, in all matters relatedto the reproductive system and to its functions andprocess”. This definition is taken and modified from theWHOdefinitionofhealth.1Reproductivehealth

Reproductive Healthaddresses the human sexuality and reproductiveprocesses, functions and system at all stages of life andimplies that people are able to have “a responsible,satisfying and safe sex life and that they have thecapability to reproduce and the freedom to decide if,when and how often to do so.”Men and women have the right to be informed and haveaccess to safe, effective, affordable and acceptablemethods of their choice for the regulation of fertilitywhich are not against the law, and the right of access toappropriate health care services for safe pregnancy andchildbirth and provide couples with the best chance ofhaving a healthy infant. Reproductive health is life-long,beginning even before women and men attain sexualmaturity and continuing beyond a woman's onceptIt is helpful to understand the concept and to examine itsorigins. During the 1960s, UNFPA established with ” and to assist developing countries in2

Reproductive Healthaddressing them. At that time, the talk was of hicentrapment” and scarcity of food, water and rticularly in the developing world and among thepoor) coincided with the rapid increase in availability oftechnologies for reducing fertility - the contraceptive pillbecame available during the 1960s along with the IUDand long acting hormonal methods.In 1972, WHO established the Special Program ofResearch, Development and Research Training inHuman Reproduction (HRP), whose mandate wasfocused on research into the development of new andimproved methods of fertility regulation and issues ofsafety and efficacy of existing methods. endent of people’s ability to practice restraint, andmore effective than withdrawal, condoms or periodicabstinence. Moreover, they held the promise of beingable to prevent recourse to abortion (generally practicedin dangerous conditions) or infanticide. Populationpolicies became widespread in developing countriesduring the 1970s and 1980s and were supported by UN3

Reproductive Healthagencies and a variety of NGOs of which internationalplanned parenthood federation (IPPF) is perhaps themost well known.The dominant paradigm argued that rapid populationgrowth would not only hinder development, but wasitself the cause of poverty and underdevelopment.Almost without exception, population policies focused onthe need to restrain population growth; very little wassaid about other aspects of population, such as changesin population structure or in patterns of migration. Giventheir genesis among the social and economic elites, it isperhaps hardly surprising that the family planningprograms that resulted were based on top-downhierarchical models and that their success was judged interms of numeric goals and targets – numbers of familyplanning acceptors, couple-years of protection, numbersof tubal ligations performed. Donors, anxious todemonstrate that their aid money was being well-spent,encouraged such performance evaluation indicators. Inthe drive for efficiency and effectiveness, they supportedthe establishment of free-standing “vertical” familyplanning bodies, generally quite separate from otherrelated government sectors such as health, often,4

Reproductive Healthindeed, set up within the office of the president or theprime minister as a mark of their importance.The 1994 ICPD has been marked as the key event inthe history of reproductive health. It followed someimportant occurrences that made the world to think ofother ways of approach to reproductive health. Whatwas the impetus behind the paradigm shift that Cairorepresents and that has been reinforced in the recentspecial session of the UN General Assembly? Threeelements are of particular importance. The first was the growing strength of thewomen’s movement and their criticism of theover-emphasis on the control of female fertility and by extension, their sexuality - to theexclusion of their other needs. A second key development was the advent ofthe HIV/AIDS pandemic; suddenly it becameimperative to respond to the consequences ofsexualactivityotherthanpregnancy,inparticular sexually transmitted diseases. Butperhaps more important, it became possible(and essential) to talk about sex, about sexual5

Reproductive Healthrelations outside of marriage as well as within it,and about the sexuality of young people. A third development, that brought a unity to theothers, was the articulation of the concept al human rights treaties in terms ofwomen’s health in general and reproductivehealth in particular gradually gained acceptanceduring the 1990s.Three rights in particular were identified: The right of couples and individuals to decidefreely and responsibly the number and spacingof children and to have the information andmeans to do so; The right to attain the highest standard of sexualand reproductive health; and, Therighttomakedecisionsfreeofdiscrimination, coercion or violence.Subsequent articulations of reproductive rights havegone further, so that, for example, maternal death isdefined as a “social injustice” as well as a “health6

Reproductive ernments to address the causes of poor maternalhealth through their political, health and legal systems.These strands became fused in the concept ofreproductive health, which was first clearly articulated inthe preparations for Cairo and which has become acentral part of the language on population. The newparadigm reflects a conceptual linking of the discourseon human rights and that on health. It proposes a radicalshift away from technology-based, directive, tion. It argues that it is possible to achievethe stabilization of world population growth, whileattending to people’s health needs and respecting theirrights in reproduction. It reinforces and gives legitimacyto the language of health and rights, and validatesconcerns raised by the international women’s movementand by health professionals who had recognized theneeds of people in sexuality and reproduction beyondfertility regulation.7

Reproductive Health1.2.DevelopmentofReproductiveHealthBefore 1978 Alma-Ata Conference Basic health services in clinics andhealth centersPrimary health care declaration 1978 MCHservicesstartedwithmoreemphasis on child survival Family planning was the main focus formothersSafe motherhood initiative in 1987 Emphasis on maternal health EmphasisonreductionofmaternalmortalityReproductive health, ICPD in 1994 Emphasis on quality of services Emphasis on availability and accessibility Emphasis on social injustice Emphasis on individuals woman's needs andrights8

Reproductive HealthMillennium development goals and reproductivehealth in 2000 MDGs are directly or indirectly related to health MDG 4, 5 and 6 are directly related to health,while MDG 1,2,3, and 7 are indirectly related tohealth World Summit 2005, declared universal accessto reproductive health “Sexual and reproductive health is fundamentalto the social and economic development ofcommunities and nations, and a key componentof an equitable society.”The Lancet 20069

Reproductive Health1.3. Magnitude of Reproductive HealthProblemThe term “Reproductive Health “is most often equatedwithoneaspectof women’slives;motherhood.Complications associated with various maternal issuesare indeed major contributors to poor reproductivehealth among millions of women worldwide.Half of the world’s 2.6 billion women are now 15 – 49years of age. Without proper health care services, thisgroup is highly vulnerable to problems related to sexualintercourse, pregnancy, contraceptive side effects, etc.Death and illnesses from reproductive causes are thehighest among poor women everywhere. In societieswhere women are disproportionately poor, illiterate, andpolitically powerless, high rates of reproductive illnessesand deaths are the norm. Ethiopia is not an exception inthis case. Ethiopia has one of the highest maternalmortality in the world; it is estimated to be between 566– 1400 deaths per 100,000 live births. Ethiopian DHSsurvey of 2005 indicates that maternal mortality is673per 100,000 live births. In Ethiopia, contraceptionuse in women is 14.7% and about 34% of women want10

Reproductive Healthto use contraceptive, but have no means to do soaccording to the Ethiopian Demographic and HealthSurvey (EDHS 2005).Women in developing countries and economicallydisadvantaged women in the cities of some industrialnations suffer the highest rates of complications ductive cancers. Lack of access to comprehensivereproductive care is the main reason that so manywomen suffer and die. Most illnesses and deaths fromreproductive causes could be prevented or treated withstrategies and technologies well within reach of even thepoorest countries. Men also suffer from reproductivehealth problems, most notably from STIs. But thenumber and scope of risks is far greater for women for anumber of reasons.11

Reproductive Health1.4. ComponentsofReproductiveHealth Quality family planning services Promoting safe motherhood: prenatal, safedelivery and post natal care, including breastfeeding; Prevention and treatment of infertility Prevention and management of complications ofunsafe abortion; Safe abortion services, where not against thelaw; Treatmentofreproductivetractinfections,including sexually transmitted infections; Information and counseling on human ctive health; Active discouragement of harmful practices, suchas female genital mutilation and violence relatedto sexuality and reproduction; Functional and accessible referral12

Reproductive HealthThe approach recognizes the central importance ofgender equality, men's participation and responsibility.2. Reproductive health indicatorsFollowing on a number of international conferences inthe 1990s, in particular the 1994 ICPD, many countrieshave endorsed a number of goals and targets in thebroad area of reproductive health. Most of these goalsand targets have been formulated with quantifiable andtime-bound hindicatorsA health indicator is usually a numerical measure whichprovides information about a complex situation or event.When you want to know about a situation or event andcannot study each of the many factors that contribute toit, you use an indicator that best summarizes thesituation. For example, to understand the general healthstatus of infants in a country, the key indicators areinfant mortality rates and the proportion of infants of lowbirth weight. Maternal health care quality, availability13

Reproductive Healthand accessibility can be measured using maternalmortality.Reproductive health indicators summarize data whichhave been collected to answer questions that arerelevant to the planning and management of RHprograms. The indicators provide a useful tool to tion and impact. Indicators are expressed interms of rates, proportions, averages, categoricalvariables or absolute numbers.2.1. CRITERIA FOR SELECTINGINDICATORSIndicator selection raises technical questions about theimplications of data collection as well as otheroperational issues. A good indicator has a number ofimportant attributes, and those recommended by theWorld Health Organization (WHO, 1997c) are outlinedbelow.14

Reproductive Health1. To be useful, an indicator must be able to act as a“markerofprogress”towardsimprovedreproductive health status, either as a direct orproxy measure of impact or as a measure ofprogress towards specified process goals.2. To be scientifically robust, an indicator must bea valid, specific, sensitive and reliable reflection ofthat which it purports to measure. A valid indicatormust actually measure the issue or factor it issupposed to measure. A specific indictor must onlyreflect changes in the issue or factor underconsideration. The sensitivity of an indicatordepends on its ability to reveal important changesin the factor of interest. A reliable indicator is onewhichwouldgivethesamevalueifitsmeasurement was repeated in the same way onthe same population and at almost the same time.3. Toberepresentative,anindicatormustadequately encompass all the issues or populationgroups it is expected to cover.15

Reproductive Health4. To be understandable, an indicator must besimple to define and its value must be easy tointerpret in terms of reproductive health status.5. To be accessible the data required for anindicator should be available or relatively easy toacquire by feasible data collection methods thathave been validated in field trials.6. To be ethical, an indicator requires data which areethical to collect process and present in terms ofthe rights of the individual to confidentiality,freedom of choice in supplying data, and informedconsent regarding the nature and implications ofthe data required.These indicators can be input, process, out-put andimpact indicators.16

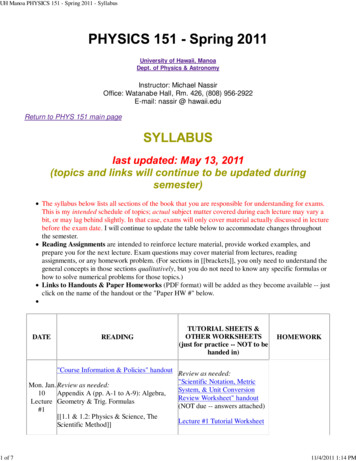

Reproductive HealthFigure 1: A Conceptual Framework for Monitoring andEvaluating Reproductive Health Programme tions orbidity

Reproductive HealthPolicies &ProductsProceduresAdvocacy and IECNational policiesContraceptivesand legislationLogisticsSource: A.T.P.L. Abeykoon (1999).2.2. Sources of data Routine service statistics: summaries of healthservice records can give information and it isvery cheap, but may be incomplete or sometimesmay not give enough information. It gives inputand process indicators. PopulationCensus:Thedatacollectedatpopulation censuses such as population by ageand sex, marital status, and urban and ruralresidence provide the denominator for theconstruction of process, output and impactindicators. Vital statistics reports: The vital registrationsystem collects data on births, deaths andmarriages. These data are available by age, sex18

Reproductive Healthandresidence.Thesedataprovidethenumerator for the construction of process, outputand impact indicators. Special studies: collection and summarization ofinformation for a particular purpose. Sample surveys : For Example Demographic andHealth survey2.3. Reproductive Health Indicators forGlobal MonitoringThere are seventeen reproductive health indicatorsdeveloped by the United Nation Population Fund(UNFPA). The list and description of these indicators aregiven below.1. Total fertility rate: Total number of children awomanwouldhavebytheendofherreproductive period, if she experienced thecurrently prevailing age-specific fertility ratesthroughout her childbearing life. TFR is one ofthe most widely used fertility measures to assessthe impact of family planning programmes. The19

Reproductive Healthmeasure is not affected by the age structure ofthe female population.2. Contraceptiveprevalence(anymethod):Percentage of women of reproductive age whoare using (or whose partner is using) acontraceptive method at a particular point intime.3. Maternal mortality ratio: The number ofmaternal deaths per 100 000 live births fromcauses associated with pregnancy and childbirth.4. Antenatal care coverage: Percentage ofwomenattended,atleastonceduringpregnancy, by skilled health personnel forreasons relating to pregnancy.5. Births attended by skilled health personnel:Percentage of births attended by skilled healthpersonnel. This doesn’t include births attendedby traditional birth attendants.20

Reproductive Health6. Availability of basic essential obstetric care:Number of facilities with functioning basicessential obstetric care per 500 000 population.Essential obstetric care includes, Parenteralantibiotics, Parenteral oxytocic drugs, Parenteralsedatives for eclampsia, Manual removal ofplacenta, Manual removal of retained products,Assisted vaginal delivery. These services can begiven at a health center level.7. ssentialfacilitieswithfunctioning comprehensive essential obstetriccare per 500 000 population. It nsfusion facilities.8. Perinatal mortality rate: Number of perinataldeaths (deaths occurring during late pregnancy,during childbirth and up to seven completed daysof life) per 1000 total births. Deaths which occurstarting from the stage of viability till completionof the first week after birth (22 weeks of gestationup to end of first week after birth, WHO). Total21

Reproductive Healthbirth means live birth plus IUFD born after fetusreached stage of viability.9. Low birth weight prevalence: Percentage oflive births that weigh less than 2500 g.10. 10. Positive syphilis serology prevalence inpregnant women: Percentage of pregnantwomen (15–24) attending antenatal clinics,whose blood has been screened for syphilis, withpositive serology for syphilis.11. Prevalence of anaemia in women: Percentageof women of reproductive age (15–49) screenedfor haemoglobin levels with levels below 110 g/lfor pregnant women and below 120 g/l for nonpregnant women.12. Percentage of obstetric and gynaecologicaladmissions owing to abortion: Percentage ofall cases admitted to service delivery pointsproviding in-patient obstetric and gynaecologicalservices, which are due to abortion (spontaneousand induced, but excluding planned terminationof pregnancy)22

Reproductive Health13. . Reported prevalence of women with FGM:Percentageofwomeninterviewedinacommunity survey, reporting to have undergoneFGM.14. Prevalence of infertility in women: Percentageof women of reproductive age (15–49) at risk ofpregnancy (not pregnant, sexually active, noncontraception and non-lactating) who reporttrying for a pregnancy for two years or more.15. Reported incidence of urethritis in men:Percentage of men (15–49) interviewed in acommunity survey, reporting at least one episodeof urethritis in the last 12 months.16. omen(15–24)attending antenatal clinics, whose blood hasbeen screened for HIV, who are sero-positive forHIV.17. .KnowledgeofHIV-relatedpreventionpractices: The percentage of all respondentswho correctly identify all three major ways of23

Reproductive Healthpreventing the sexual transmission of HIV andwho reject three major misconceptions about HIVtransmission or prevention.3. Gender and Reproductive HealthSex refers to biological and physiological attributes ofthat identify a person as male or femaleGender refers to the economic, social and culturalattributes and opportunities associated with being maleor female in a particular social setting at a particularpoint in time.Gender equality means equal treatment of women andmen in laws and policies, and equal access to resourcesand services within families, communities and society atlarge.Gender equity means fairness and justice in thedistribution of benefits and responsibilities betweenwomen and men. It often requires women-specificprogrammes and policies to end existing ction,exclusion or restriction made on the basis of socially24

Reproductive Healthconstructed gender roles and norms which prevents aperson from enjoying full human rights.Gender stereotypes refer to beliefs that are soingrained in our consciousness that many of us thinkgender roles are natural and we don’t question them.Genderbias referstogenderbasedprejudice;assumptions expressed without a reason and aregenerally unfavorable.Gender mainstreaming: the incorporation of genderissues into the analysis, formulation, implementation,monitoring of strategies, programs, projects, policies andactivities that can address ine

the drive for efficiency and effectiveness, they supported the establishment of free-standing "vertical" family planning bodies, generally quite separate from other related government sectors such as health, often, Reproductive Health 5 indeed, set up within the office of the president or the