Transcription

NEUROSCIENCE AND PEACEBUILDING:Reframing How We Think About Conflict and PrejudiceJanuary 21-22, 2015

NEUROSCIENCE AND PEACEBUILDING:Reframing How We Think About Conflict and PrejudiceJanuary 21-22, 2015

ABOUT THE REPORTThis report summarizes discussion and findings presentedMelinda Burrell (independent researcher) and Judyat a conference organized by the El-Hibri Foundation (EHF),Barsalou (retired EHF President) prepared this report.Beyond Conflict (BC) and the Alliance for PeacebuildingThe conference operated on the basis of non-attribution(AfP). The conference was held at the El-Hibri Foundation in“Chatham House rules,” with only panel presenters associatedWashington, DC on January 21-22, 2015 and was attended byby name with their comments.neuroscientists, experimental psychologists, peacebuildingpractitioners, policymakers and others interested in howhuman brain functions shape conflict, identity formation,prejudice and peacebuilding. The purpose of the conferencewas to highlight relevant issues uncovered by neuroscientistsand psychologists about behavior and conflict through theirresearch focused on the brain; to identify issues of commoninterest to the neuroscience and peace building communitiesand the donors that fund them; andto promote greater collaboration between thesecommunities going forward.2

ABOUT THE CONVENERSThe El-Hibri Foundation is a private foundation basedThe Alliance for Peacebuilding is a global membershipin Washington, DC that seeks to build a better world byassociation of nearly 100 peacebuilding organizations, 1,000embracing two universally shared values of Islam: peaceprofessionals, and a network of more than 15,000 peopleand respect for diversity. The Foundation supports peacedeveloping processes for change in the most complex,education and interreligious cooperation through grantschaotic conflict environments in the US and aroundfor promising groups, awards that recognize leadership andthe world.programs that promote learning and bridge-building.Beyond Conflict assists leaders in divided societiesstruggling with conflict, reconciliation and societal changeby facilitating direct contact with leaders who havesuccessfully addressed similar challenges in other settings.Beyond Conflict realizes its mission through two types ofprogramming: in country programs and thematic initiativesthat address global challenges to peace and reconciliation. In2012, Beyond Conflict launched the Neuroscience and SocialConflict Initiative, which seeks to utilize recent advancesin the cognitive sciences to better address conflict andreconciliation around the world, in partnership with MIT.3

KEY FINDINGSA revolution is currently taking place in brain science. Withthan by cognitive processes. Individuals’ awareness of their own bias may helprecent access to new technologies, leading neuroscientiststhem reduce its power; it appears to be possible toare putting the most sophisticated tools available to theintentionally “re-wire” the brain by exposing it to “positivetask of understanding how the brain processes experienceexemplars” that contradict negative stereotypes.in ways that shape tendencies toward cooperation orconfrontation. As a result, there is a growing body of researchHumans have the capacity to empathize with andand an emerging understanding of the neurobiological“mentalize” (think about) the feelings and beliefsunderpinnings of key processes and experiences, such as fear,of others, but we experience our own thoughts andtrauma, bias, memory, empathy, exclusion and humiliation,emotions as the most real and salient/first and foremost.many of which are driven by unconscious cognitive dehumanization when thinking about others.processes. These findings offer a new framework or lens foraddressing persistent challenges faced in conflict resolution,Mentalizing, in short, inevitably leads to some level of Humanization of others is not automatic but can triggerreconciliation, peace-building and diplomacy. Key findingsa sense of empathy and interdependence between ordiscussed at this meeting are summarized below:among individuals and groups. primed, without our conscious awareness, for both pro-Human behavior is largely driven by emotions: Often “hair triggers” are sufficient. We can be easilysocial and anti-social behavior.Recent research challenges the prevailing belief thathuman action results primarily from rational thought processes. At our core, we are emotional beings whoSocial norms strongly influence human thoughtbehave rationally primarily when we feel secure andand behavior:validated. We are highly social beings, taking our cues from theFear, which is largely regulated by the amygdala, affectssocial norms evident in the behavior of others, and weintergroup dynamics and the tendency to embrace theexpect reciprocity.use of violence in response to a perceived threat. Compared to individual attitudes, social norms areequally important, if not more important, influences onbehavior.Individuals are largely unaware of how their brainsrespond to the surrounding environment: successful if they reflect subtle understanding ofor decision-making rules, in part because the brain hasprescriptive norms and the brain’s unconsciouslimited cognitive ability. Behaviors such as prejudice,processing of messages. Effective messages are those that are relevant to theunconscious brain processes.identity of the person being targeted and that indicateWe process information rapidly, using a variety of biasesthe relationship between a widely practiced social normand heuristics, independently of the rational processingand the desired behavior.of information. Efforts to change behavior are more likely to beOur brains use automatic systems influenced by normsstereotyping and dehumanization reflect these How we perceive an “out” group different from our ownis more influenced by affective (or emotional) processes4

Melanie GreenbergAlliance for Peacebuilding5

Group identities are simultaneously lastingconflict management. For example, apologies and otherand malleable:non-material incentives, can lead to flexibility around Individual and group behavior is highly influenced bygroup identity. Our brains are hard-wired to cooperate sacred values. Even the most extreme believers can show flexibility if awithin “our” group while competing with other groups.symbolic gesture is offered by the other side, especiallyWe are quick to form and identify with groups, regardlessif it represents a sacrifice for that side or a significantof situation.compromise that benefits many.Broadening the definition of “we”—that is, encouragingconflict protagonists to construct more inclusivePeacebuilding efforts can easily backfire if they only relyidentities—is one strategy to potentially reduce conflict.on intuitions and ignore the underlying drivers of humanFor peace builders, group identity defined around thebehavior:use of violence suggests the need to reformulate that identity.Peacebuilding programs can have unintendedconsequences when they fail to account for howunconscious brain processes interact with consciousStereotyping is largely driven by an unconsciousassessment of threats: awareness to shape our behavior. Awareness of how the brain works can help peaceManaging rather than eliminating stereotypes may bebuilders design programs that create “safe” environmentsa more realistic goal. Reducing stereotypes is aided bythat foster circumstances conducive to re-humanizingcounter-intuitive exemplars and heterogeneous imagesenemies and reducing conflict. Essential elementsof the “out” group.include addressing power asymmetries, producingPurely positive images of a stereotyped group caninteractions where participants feel their grievances arereinforce existing, negative stereotypes of that group.heard and their perspectives are understood, reducingGiven the influence of social norms, prejudice reductionhumiliation and anticipating competing, negativeneeds to take into account the full complexity ofmessages.the environment that acts upon individuals, ranging While building trust can be important, it may be bestfrom influences from within the family and the localto focus first on breaking down biases and engaging incommunity to messages purveyed by policymakers andperspective-taking, rather than prioritizing improvedthe media.personal relationships. Many “contact” programs are successful in buildingHuman behavior is also influenced by so-called “sacredtrust among their participants. However, if the newlyvalues”—deeply held beliefs or taboos that often havesensitized participant returns to his or her homenothing to do with religion:community and has negative interactions with a member In conflict situations, understanding how communitiesof the other group, he or she may feel betrayed andand individuals define their own sacred values is crucial.develop even deeper animosity towards the group.Sacred values are malleable under the right Few peacebuilding programs incorporate effectivecircumstances.evaluations based on randomized samples and controlSymbols and symbolic acts, such as public apologies,groups that provide insights into what primes humanpertaining to sacred values powerfully affect conflict andbehavior and which strategies work.6

Judy BarsalouEl-Hibri Foundation7

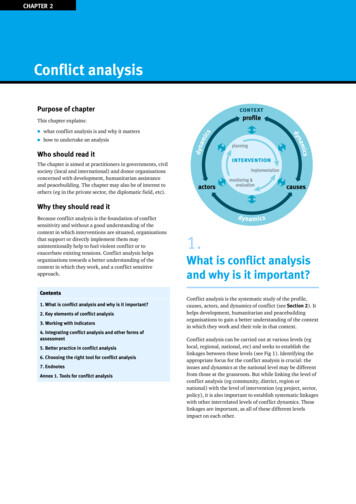

FULL DISCUSSION SUMMARYprescriptive norms and how the brain processes messagesabout them. For example, an anti-rape campaign basedI. RESEARCH INSIGHTS ABOUT HOW THEBRAIN WORKSon the statement that rape is a widespread practice onTim Phillips asked, “What can people learn from theacceptable behavior. An anti-littering campaign that displaysbehavior of others?” He challenged the widespread beliefpictures of wide-strewn trash suggests that littering is athat perception and behavior are highly differentiatedcommon practice. People will decrease their consumption ofaccording to context, noting that the neurosciences tell usclean towels in hotels or the use of electricity in their homes ifthat people respond to fear, humiliation, trauma and loss ofsocial messages on those issues indicate that restricted towelagency in very similar ways around the world, regardless ofor energy use is widely embraced. “General” and “stereotyped”context. Human beings everywhere share the same biologicalthreats also unconsciously influence behavior. The latter, for“operating system” and are wired for survival. Insights fromexample, can reduce performance on IQ tests for membersneuroscience, he argued, are fundamentally reframing ourof groups stereotyped as less intelligent. Fear and “disgust”understanding of what it means to be human and whatamplify the sense of threat.college campuses subtly sends the message that rape is andrives human behavior.Neuroscience is still mapping out the brain’s modularUnconscious Processingcomponents, how they interact together, and the brain’sBolstering Phillips’ argument that we are emotional beingsmalleable “plasticity.” The brains of those suffering fromwho act rationally only when we feel secure and validated,post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) based on exposureEmile Bruneau noted that humans are largely unconsciousto or participation in violent conflict show lasting physicalof how their brains operate. The brain is a modular processordeformations of the pre-frontal cortex.(akin to a “Swiss army knife”), with different parts of the braintaking up and using information to perform tasks, some ofNeuroimaging, a basic tool of neuroscience, provides insightswhich are beyond the consciousness and introspection ofinto brain activity of which the individual is unaware—thatthe individual. Illustrating this point, he evoked Jonathanis, it allows us to examine the elephant. Bruneau asserted,Haidt’s metaphor of the elephant and the rider (The Happinesshowever, that experimental psychology offers the mostHypothesis, New York: Basic Books, 2006): A person is like aimmediate and accessible insights into what guides humansmall rider sitting astride a powerful elephant, with the riderbehavior. Research methodologies employed by both fieldsrepresenting rational brain functions of which the rider isare needed because together they help us understandconscious. The elephant, on the other hand, is the larger,that common sense interventions can have unintendedemotional part of the brain unreached by rational thinkingconsequences. Even efforts to evaluate the effect of anthat dominates action based on environmental stimuli andintervention through retrospective questioning may point toprescriptive norms. The rider believes that he or she is inmisleading conclusions, because unconscious processes ofcontrol of the elephant, but that is an illusion.the brain may point to different, unexpected conclusions. Forexample, well-meaning programs designed to reduce ethnicBehavior is strongly and often unconsciously guided bystereotyping and bias may unconsciously reinforce bias,messaging about prescriptive norms. For that reason, effortsespecially if they depict the “out” group as wholly good andto change behavior should reflect subtle understanding ofundifferentiated.8

Tim PhillipsBeyond Conflict(foreground)Chip HaussAlliance for Peacebuilding9

“Mirroring” and “Mentalizing”Adam Waytz argued that humanization and dehumanizationare key to understanding our ability to relate to or empathizewith others. Dehumanization involves seeing another personas “mindless,” or somehow less than fully human. Two types ofbrain functions are important: “mirroring,” which allows us tovicariously “experience” another person’s mental state, feelingtheir pain or pleasure; and “mentalizing,” a brain process thatleads us to imagine or infer what another person is thinking.Mina Cikara noted that people tend to mentalize more aboutan “out” group they perceive as threatening, and do so lessin relation to groups with whom they are not in competition.An individual’s degree of social connection to a group affectstheir focus on their own group at the expense of others.Humanizing others does not happen automatically. There are“triggers” that facilitate humanization and dehumanizationas well as apathy or a sense of distance from others. Cikaradefined apathy as an absence of feeling, but one that isvery different from antipathy. She described outcomes fromexperiments focused on assessing others based on degreesof perceived “warmth” and “competence,” with individualsmentally engaging more with those whom they perceive tobe competent. Triggers relating to dehumanization relate tothe other’s perceived boundaries, borders and dissimilarities,as well as to their access to power and resources. Regardlessof these factors, Waytz argued that we never experienceothers’ emotions and minds as profoundly as we experienceour own—a process that inevitably leads to some levelof “dehumanization” when thinking about others. Hesuggested that future research should focus as much onapathy and antipathy as on the triggers that increase a senseof interdependence with others. Apathy toward others isinfluenced by dissimilarities between groups, their relativepower and access to resources, and social connections withinone’s own group. Regarding apathy, Waytz quoted GeorgeBernard Shaw: “The worst sin toward our fellow creatures is notto hate them but to be indifferent toward them; that’s the10Mina CikaraHarvard University(left)Adam WaytzNorthwestern University(center)Salma ElbeblawiSoliya(right)

11

essence of inhumanity.” Behavior that is perceived as arroganceAnonymity as a group member mitigates a sense of personalmay reflect a person’s fear, an insight that can foster different,responsibility. The “bystander effect” relates to a group’smore productive conversations about peace building.diffused sense of responsibility until one person takes action,even at the risk of their own safety. That action can unlockIdentity Formationthe actions of others. Courageous individuals, sometimesAccording to findings outlined by Cikara, identities are veryinspired by others who behaved similarly, can deviate from“plastic” or malleable. Researchers now understand bettergroup behavior based on social norms that promote harmhow people form identities as members of groups, howto others, acting on a moral precept. Examples of such actsidentity affects cognition and behavior, and how identityinclude sheltering targets of genocide at the risk of personalcan be manipulated or changed. People who identify with asafety. More research is needed to understand what triggersgroup are easily swept up by its prescriptive norms, alteringcourageous behavior based on moral values promoting non-their behavior and memory; participants in riots often say, “Iviolence.don’t know what came over me” as they unexpectedly foundthemselves joining the action. The brain chemical oxytocinSacred Values and Symbolic Gesturespowerfully affects identity and group formation.Jeremy Ginges noted that conflicts can become more violentand intractable when protagonists possess “sacred values”—Competition, Cikara argued, strongly affects mentalizing.deeply held beliefs or taboos that often have nothing to doIdentifying with a group may cause an individual towith religion. He noted that humans often ascribe monetaryreframe or justify their actions as serving the greater good,value to things, but some issues cannot easily be reduced toespecially in a competitive context in which the only waymonetary terms, and efforts to do so are considered taboo.for the individual or group to “win” is by harming others.He cited as one such example compromise over the status ofAn individual’s own moral standards may be overridden byJerusalem, which caused participants in one study to signaltheir identification with a group, but efforts to increase theincreased support for violence when material goods weresalience of moral standards can decrease a tendency to justifyoffered as an incentive for giving up Jerusalem, regardlessor engage in violence. Research by Emily Falk reinforces theof how the bargain was phrased or to whom the benefitnotion that an individual’s experience is shaped by whetheraccrued.they are part of an “empowered” or “disempowered” group.Ginges noted, however, that sacred values are not absolute,Expanding on the above, Linda Tropp explained that whenand even the most extreme people show flexibility if thepeople think of themselves as group members, they tendother side offers a symbolic gesture, especially if it representsto exaggerate differences and create more rigid boundariesa compromise or sacrifice for the latter. Such symbolic actsbetween groups. They also are motivated to preserve acan lead to flexibility when material bargaining will not. Inpositive image of their own group, give more resources toterms of the Israeli/Palestinian conflict, the same people whotheir own group, and ascribe more positive interpretationshowed support for violence when offered material goodsof behavior and intentions to their own group. Exacerbateddemonstrated less “disgust” and “humiliation” and supportedby perceived threats during uncertain times, these groupcompromise if the other side undertook a powerful symbolicprocesses are strengthened by unity within groups and byact – such as Israel apologizing to Palestinians or Palestinianslong-term legacies of conflict.in exile foregoing the right to return to Israel. Ginges noted12

Jeremy GingesNew School For Social Research(foreground)Linda TroppUniversity of Massachusetts, Amhesrt13

Emile BruneauMIT SaxeLab (foreground)Hal SaundersKettering Foundation14

anecdotally that the less powerful group (in this case, theactivism. Interestingly, positive contact with an “out” groupPalestinians) is more likely to sacralize issues, but both sidesproduced more affective changes (how the groups felt abouttend to see themselves as victims.each other) versus cognitive changes (how they thoughtabout the other), although positive contact also inclinedFurther discussion of sacred values included whether orgroups to regard the others’ intentions more positively.not there is a perceived loss of status when a group isasked to give up something of sacred value to them, and ifIn short, psychological processes associated with groupcompromise is more likely if a similar compromise is askedmembership can inform strategies to reduce, reframe orof the other group. More research is needed, argued Ginges,transform conflict. Understanding those processes can leadwho noted that offering to compromise on a sacred valueto the design of more effective contact programs. Manymay cause the contending group to devalue its importance.practitioners assume that contact knowledge leads toreduced prejudice. In reality, lower anxiety and a reducedsense of threat produce less prejudice, as does increasedII. IMPLICATIONS FOR PEACEBUILDINGPRACTITIONERSempathy, because prejudice is based more on emotionalPromoting Contactbetween groups, therefore, encouraging perspective sharingThousands of peacebuilders have tried to reduce conflict byand cooperative norms are important strategies. Morefacilitating meaningful contact among conflict protagonists.broadly, prescriptive norms can be shifted through media“Contact theory” posits that sustained interactions amongcampaigns, anti-bias education and efforts to reframe groupsmall groups can promote humanization, empathy andidentity, whereby people see themselves as part of a broadercompromise.whole that promotes positive contact within the wider groupprocesses than on rational thought. To reduce conflictas the norm.To understand the effect of intergroup contact, Troppconducted a “meta-review” of 515 studies undertakenMuch discussion focused on changing norms relating tobetween the 1940s and 2000 based on 713 independentviolence as an important goal for peace builders. We thinksamples, and concluded that they demonstrated a positiveabout violence as doing harm, but in many contexts peoplerelationship between higher contact and lower prejudice.regard those engaging in violence as self-sacrificing heroes.She cautioned, however, that the type of contact matters.One goal of peacebuilding interventions could be to gainPositive outcomes are the result of structured versus adacceptance of new norms relating to heroism and self-hoc contact moments and reflect efforts to promote equalsacrifice based on non-violent resolution of conflict.status between the contact groups. Regarding groups withasymmetrical power, positive contact generally had lessHal Saunders shared insights gleaned from years ofimpact on members of the non-dominant group, but thatpeacebuilding practice in diverse settings. He stressed thechanged somewhat when the program created close andpower of extended interactions to transform relationships,meaningful relationships. Also, if a minority group had moreand the importance of transforming relationships withinpositive contact with a majority group, the minority groupthe broader society, not just among government officials—tended to perceive lower levels of discrimination against theirsomething that takes years and multiple engagements.own group and expressed less desire to be involved in ethnicEnemies negotiating together can create a cumulative15

Daanish MasoodUnited Nations16

agenda for advancing peace. Over time, they develop acommon body of knowledge about the issues at the heartIf not carefully managed, contact programs can inflateof the conflict and how the other side views them, enablingexpectations and worsen problems when they lead tothem to solve problems together.perceived betrayal of newly established trust. Studies haveshown that when contact group participants return home,Saunders stressed the temporal elements of peacebuilding—interactions with a member of the other group—suchthe need to think in terms of years and even decades,as mistreatment at a checkpoint—can lead to feelingsversus weeks or months—devoted to the developmentof betrayed trust. Program design needs to account forof relationships and exploration of issues. He and othersthis possibility. Some argued that a primary goal of suchcautioned against being too efficient and “rushing toprograms should not be to engender trust but to createharmony.” Saunders argued that if protagonists start gettingsituations where disempowered groups feel they arealong better immediately, the higher status group might“heard” and “acknowledged” by more empowered groups.decide there is no need to compromise, and the lower statusIn negotiations, compromise is less likely when one sidegroup might not feel empowered to air their grievances.perceives that it is being asked to give up somethingProtracted conflict puts more issues on the table whileimportant before it is heard and understood.leading to multiple opportunities to share informationand promote transparency. In response, Cikara notedAddressing Victimization, Psychological Trauma andthat research scientists largely ignore temporal aspect ofDehumanizationpeacebuilding, an issue that requires more study.A lack of agency—when an individual or group feels unableto act—is related to a sense of victimhood. It may developSalma Elbeblawi speculated that programs aiming towhen a society is subject to long-term repression, reinforcingimprove understanding between two groups may bea sense of apathy that individuals can not influence theirfundamentally flawed if they start by defining the groups insurroundings. Discussants agreed that more research isopposition to each other—such as “Westerners” versus “Arabs”needed to understand when and how individuals and groupsor “Muslims.” She argued that peacebuilding practitionersdevelop a sense of agency. Currently, programs to restoreshould learn more about triggers that help to humanize otheragency in such populations are largely political in nature, andgroups and reduce negative stereotypes. Positive outcomestheir impact is not well understood.require sustained communication over time, opportunities forpersonalized experience by individual participants and effortsThere also was much discussion about the practicalto promote equal status between the participants based ondimensions of dehumanization, including what it means totheir group identity. All these aims are difficult to achieve,be dehumanized as an individual versus as a member of abut one best practice is to have two groups collaborate onlarger group. Identities are malleable and can change quicklyjoint projects. Given the strong influence of the broader socialdepending on context. Treating groups monolithically—environment and prescriptive norms, she argued that suchseeing people not as individuals but only as members ofprograms need to address their goals from different anglestheir (stereotyped) group—is a form of dehumanization.and undertake comprehensive efforts that account for the fullSeveral discussed the important of exposing people tocomplexity of participants’ social worlds—including friends,counter-intuitive exemplars from the dehumanized group—parents, social media and other influences.individuals who defy expectations about that group—in17

Dalia MogahedInstitute for Social Policy and Understanding18

efforts to overcome stereotypes about the group. Well-Muslims. It also encourages shifts in homophily (the tendencyintentioned programs may backfire if they depict the groupfor people to like and bond with “similar others”) based onas an undifferentiated mass. The “in” group is more familiartheir social networks.with itself and can dissociate outlying actions of an individualbelong to that group, but it does not do so for “out” groups.Alex Kronemer and Daniel Tutt argued for the power ofThis dynamic can create more radicalism if individuals arepositive storytelling. Literature, they asserted, can buildhumiliated by perceptions about the bad behavior of anempathy, but television and film do so even more powerfully.individual in their group. In this connection, discussantsAccordingly, Unity Productions Foundation (UPF) producesreferenced the discomfort of ordinary Muslims called uponfilms that focus on positive and unexpected representationsto apologize for the violent behavior of a few. One approachof remarkable Muslims. Tutt reinforced an earlier point whenis to try to redefine the boundaries of the group, creating ahe described a failed experiment conducted in a Paris suburblarger “we,” but flawed efforts may inadvertently reinforcethat strengthened negative stereotypes when it depictedexisting group categories.an “out” group only through positive images. AttitudesSome discussants suggested it is better to break down biasesabout Muslims and Islam will change fastest throughthat get in the way of rational thought processes ratherheterogeneous representations in media, television, film andthan focusing on improving personal relations, which areother venues.subject to many unconscious influences. One suggested thatchanging individual attitudes may be the wrong target and,Dalia Mogahed argued that Islamophobia is a sort ofinstead, we should focus on building institutions that change“canary in the coal mine,” because a loss of rights by Muslimssocial norms. Others argued that it is not so important ifpresages a loss of rights by others. Approximately 80 percentnegative attitudes remain, as long as people engage in pro-of anti-Shari’a bills, she noted, are initiated by legislators whosocial behavior.have actively sought to restrict the rights of other groups inthe US. The greatest overlap with other issues is with strictCountering Islamophobiavoter ID laws (which limit voting), right-to-work laws (whichAaron Stauffer noted that anti-Islamic bias reflects multipleundermine unions) and, to a lesser degree, with immigration,factors, and that efforts to reduce bias require identifyingabortion and same sex-marriage rights. Mogahed notedand working with the “moveable middle,” not just “preachingthat anti-Shari’a la

the individual. Illustrating this point, he evoked Jonathan Haidt's metaphor of the elephant and the rider (The Happiness Hypothesis, New York: Basic Books, 2006): A person is like a small rider sitting astride a powerful elephant, with the rider representing rational brain functions of which the rider is conscious.