Transcription

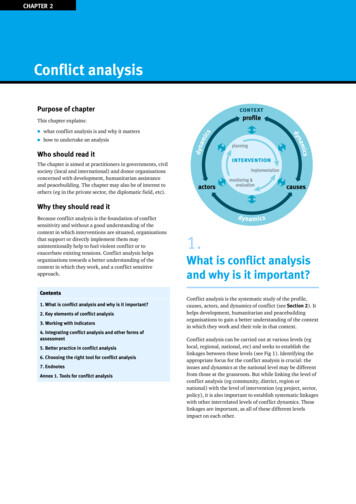

CHAPTER 2Conflict analysisPurpose of chapterThis chapter explains:lwhat conflict analysis is and why it matterslhow to undertake an analysisWho should read itThe chapter is aimed at practitioners in governments, civilsociety (local and international) and donor organisationsconcerned with development, humanitarian assistanceand peacebuilding. The chapter may also be of interest toothers (eg in the private sector, the diplomatic field, etc).Why they should read itBecause conflict analysis is the foundation of conflictsensitivity and without a good understanding of thecontext in which interventions are situated, organisationsthat support or directly implement them mayunintentionally help to fuel violent conflict or toexacerbate existing tensions. Conflict analysis helpsorganisations towards a better understanding of thecontext in which they work, and a conflict sensitiveapproach.Contents1. What is conflict analysis and why is it important?2. Key elements of conflict analysis3. Working with indicators4. Integrating conflict analysis and other forms ofassessment5. Better practice in conflict analysis6. Choosing the right tool for conflict analysis7. EndnotesAnnex 1. Tools for conflict analysis1.What is conflict analysisand why is it important?Conflict analysis is the systematic study of the profile,causes, actors, and dynamics of conflict (see Section 2). Ithelps development, humanitarian and peacebuildingorganisations to gain a better understanding of the contextin which they work and their role in that context.Conflict analysis can be carried out at various levels (eglocal, regional, national, etc) and seeks to establish thelinkages between these levels (see Fig 1). Identifying theappropriate focus for the conflict analysis is crucial: theissues and dynamics at the national level may be differentfrom those at the grassroots. But while linking the level ofconflict analysis (eg community, district, region ornational) with the level of intervention (eg project, sector,policy), it is also important to establish systematic linkageswith other interrelated levels of conflict dynamics. Theselinkages are important, as all of these different levelsimpact on each other.

2Conflict-sensitive approaches to development, humanitarian assistance and peace building:tools for peace and conflict impact assessment Chapter 2For example, when operating at the project level, it isimportant to understand the context at the level at whichthe project is operating (eg local level), so the focus of theanalysis should be at that level; but the analysis shouldalso take account of the linkages with other levels (egregional and national). And similarly when operating atthe regional, sector or national levels.2.Key elements of conflictanalysisAs discussed in Chapter 1, conflict sensitivity is about:lunderstanding the context in which you operatelunderstanding the interaction between yourintervention and the contextlacting upon the understanding of this interaction, inorder to avoid negative impacts and maximise positiveimpacts.Conflict analysis is thus a central component ofconflict-sensitive practice, as it provides the foundation toinform conflict sensitive programming, in particular interms of an understanding of the interaction between theintervention and the context. This applies to all forms ofintervention – development, humanitarian, peacebuilding– and to all levels – project, programme, and sectoral.In other words, conflict analysis will help:lto define new interventions and to conflict-sensitiseboth new and pre-defined interventions (eg selection ofareas of operation, beneficiaries, partners, staff, timeframe). (Planning stage)lto monitor the interaction between the context and theintervention and inform project set-up and day-to-daydecision-making. (Implementation stage)lto measure the interaction of the interventions and theconflict dynamics in which they are situated.(Monitoring and evaluation stage)This section synthesises the key elements of conflictanalysis as they emerge from the various conflict analysistools documented in Annex 1. Looking at each of theseelements will help to develop a comprehensive picture ofthe context in which you operate. Depending on yourspecific interest, however, you may want to emphasiseparticular aspects of key importance. For example, if theemphasis is on the identification of project partners andbeneficiaries, a good understanding of conflict actors andhow potential partners and beneficiaries relate to themwill be the primary requirement. (See Box 2 in thischapter).Generally, “good enough” thinking is required. This meansaccepting that the analysis can never be exhaustive, norprovide absolute certainty. Conflict dynamics are simplytoo complex and volatile for any single conflict analysisprocess to do them justice. Nevertheless, you should trustyour findings, even though some aspects may remainunclear. Do not be discouraged; some analysis, no matterhow imperfect, is better than no analysis at all.The following diagram highlights the common keyfeatures of conflict analysis, which will contribute tounderstanding the interaction between the context andfuture/current interventions (see Chapters 3 and 4 for theproject and sectoral (sector wide) levels respectively). Thecommon features are the conflict profile, actors, causesand dynamics. Each is further described below.

Conflict-sensitive approaches to development, humanitarian assistance and peace building:tools for peace and conflict impact assessment Chapter 22.2 Causes of conflictIn order to understand a given context it is fundamental toidentify potential and existing conflict causes, as well aspossible factors contributing to peace. Conflict causes canbe defined as those factors which contribute to people’sgrievances; and can be further described as:2.1 ProfileA conflict profile provides a brief characterisation of thecontext within which the intervention will be situated.BOX 1Key questions for a conflict profileWhat is the political, economic, and socio-cultural context?eg physical geography, population make-up, recent history,political and economic structure, social composition,environment, geo-strategic position.What are emergent political, economic, ecological, andsocial issues?eg elections, reform processes, decentralisation, newinfrastructure, disruption of social networks, mistrust, returnof refugees and internally displaced persons (IDPs), militaryand civilian deaths, presence of armed forces, mined areas,HIV/AIDS.What specific conflict prone/affected areas can be situatedwithin this context?eg, areas of influence of specific actors, frontlines around thelocation of natural resources, important infrastructure andlines of communication, pockets of socially marginalised orexcluded populations.Is there a history of conflict?eg critical events, mediation efforts, external intervention.Note: this list is not exhaustive and the examples may differaccording to the contextlstructural causes – pervasive factors that have becomebuilt into the policies, structures and fabric of a societyand may create the pre-conditions for violent conflictlproximate causes – factors contributing to a climateconducive to violent conflict or its further escalation,sometimes apparently symptomatic of a deeperproblemltriggers – single key acts, events, or their anticipationthat will set off or escalate violent conflict.Protracted conflicts also tend to generate new causes (egweapons circulation, war economy, culture of violence),which help to prolong them further.As the main causes and factors contributing to conflict andto peace are identified, it is important to acknowledge thatconflicts are multi -dimensional and multi-causalphenomena – that there is no single cause of conflict. It isalso essential to establish linkages and synergies betweencauses and factors, in order to identify potential areas forintervention and further prioritise them. Some of the toolsin Annex 1 – eg Clingendael / Fund for Peace, RTC – offermethods to assess the relative importance of differentfactors. Many tools developed for conflict analysis alsocategorise conflict causes or issues by governance,economics, security and socio-cultural factors.BOX 2Key questions for an analysis of conflict causesWhat are structural causes of conflict?eg illegitimate government, lack of political participation,lack of equal economic and social opportunities, inequitableaccess to natural resources, poor governance.What issues can be considered as proximate causes ofconflict?eg uncontrolled security sector, light weapons proliferation,human rights abuses, destabilising role of neighbouringcountries, role of diasporas.What triggers can contribute to the outbreak / furtherescalation of conflict?eg elections, arrest / assassination of key leader or politicalfigure, drought, sudden collapse of local currency, militarycoup, rapid change in unemployment, flood, increasedprice/scarcity of basic commodities, capital flight.3

4Conflict-sensitive approaches to development, humanitarian assistance and peace building:tools for peace and conflict impact assessment Chapter 2What new factors contribute to prolonging conflictdynamics?eg radicalisation of conflict parties, establishment ofparamilitaries, development of a war economy, increasedhuman rights violations, weapons availability, developmentof a culture of fear.What factors can contribute to peace?eg communication channels between opposing parties,demobilisation process, reform programmes, civil societycommitment to peace, anti-discrimination policies.Note: This list is not exhaustive and the examples may differaccording to the context.Particular attention should be paid to spoilers, ie specificgroups with an interest in the maintenance of the negativestatus quo. If not adequately addressed within theframework of preventive strategies, they may become anobstacle to peace initiatives.Similarly, it is important to identify existing institutionalcapacities for peace, in order to further define entry pointsto address causes of violent conflict. Capacities for peacetypically refer to institutions, organisations, mechanismsand procedures in a society for dealing with conflict anddifferences of interest. In particular, such actors need to beassessed in relation to their capacity for conflictmanagement, their legitimacy, the likelihood of theirengagement, and the possible roles they can adopt.BOX 4Key questions for an actor analysis2.3 ActorsPeople are central when thinking about conflict analysis.The Resource Pack uses the term “actors” to refer to allthose engaged in or being affected by conflict. Thisincludes individuals, groups and institutions contributingto conflict or being affected by it in a positive or negativemanner, as well as those engaged in dealing with conflict.Actors differ as to their goals and interests, their positions,capacities to realise their interests, and relationships withother actors (see Box 3).Who are the main actors?eg national government, security sector (military, police),local (military) leaders and armed groups, privatesector/business (local, national, trans-national), donoragencies and foreign embassies, multilateral organisations,regional organisations (eg African Union), religious orpolitical networks (local, national, global), independentmediators, civil society (local, national, international), peacegroups, trade unions, political parties, neighbouring states,traditional authorities, diaspora groups, refugees / IDPs, allchildren, women and men living in a given context. (Do notforget to include your own organisation!)BOX 3Interests, goals, positions, capacities andrelationshipslInterests: the underlying motivations of the actors(concerns, goals, hopes and fears).lGoals: the strategies that actors use to pursue theirinterests.lPositions: the solution presented by actors on key andemerging issues in a given context, irrespective of theinterests and goals of others.lCapacities: the actors’ potential to affect the context,positively or negatively. Potential can be defined in termsof resources, access, social networks and constituencies,other support and alliances, etc.lRelationships: the interactions between actors at variouslevels, and their perception of these interactions.Some approaches distinguish actors according to the levelat which they are active (grassroots, middle level, top level).In particular, conflict transformation theory attaches greatimportance to middle level leaders, as they may assume acatalytic role through their linkages both to the top andthe grassroots. In any case, it is important to consider therelationships between actors / groups at various levels andhow they affect the conflict dynamics.What are their main interests, goals, positions, capacities,and relationships?eg religious values, political ideologies, need for land,interest in political participation, economic resources,constituencies, access to information, political ties, globalnetworks.What institutional capacities for peace can be identified?eg civil society, informal approaches to conflict resolution,traditional authorities, political institutions (eg head of state,parliament), judiciary, regional (eg African Union, IGAD,ASEAN) and multilateral bodies (eg International Court ofJustice).What actors can be identified as spoilers? Why?eg groups benefiting from war economy (combatants,arms/drug dealers, etc), smugglers, “non conflict sensitive”organisations (see Chapter 1).Note: This list is not exhaustive and the examples may differaccording to the context.

Conflict-sensitive approaches to development, humanitarian assistance and peace building:tools for peace and conflict impact assessment Chapter 22.4 DynamicsConflict dynamics can be described as the resultinginteraction between the conflict profile, the actors, andcauses. Understanding conflict dynamics will help identifywindows of opportunity, in particular through the use ofscenario building, which aims to assess different possibledevelopments and think through appropriate responses.2.5 SummaryBOX 6Key questions for conflict analysisProfileWhat is the political, economic, and socio-cultural context?Scenarios basically provide an assessment of what mayhappen next in a given context according to a specifictimeframe, building on the analysis of conflict profile,causes and actors. It is good practice to prepare threescenarios: (a) best case scenario (ie describing the optimaloutcome of the current context; (b) middle case or statusquo scenario (ie describing the continued evolution ofcurrent trends); and (c) worst case scenario (ie describingthe worst possible outcome).What are emergent political, economic and social issues?If history is the key to understanding conflict dynamics, itmay be relevant to use the timeline to identify its mainphases. Try to explain key events and assess theirconsequences. Temporal patterns (eg the four-yearrotation of presidents or climatic changes) may beimportant in understanding the conflict dynamics.Undertaking this exercise with different actors and groupscan bring out contrasting perspectives.What triggers could contribute to the outbreak/ furtherescalation of conflict?What conflict prone/affected areas can be situated withinthe context?Is there a history of conflict?CausesWhat are the structural causes of conflict?What issues can be considered as proximate causes ofconflict?What new factors contribute to prolonging conflictdynamics?What factors can contribute to peace?ActorsWho are the main actors?BOX 5Key questions for an analysis of conflict DynamicsWhat are their interests, goals, positions, capacities andrelationships?What capacities for peace can be identified?What are current conflict trends?eg escalation or de-escalation, changes in importantframework conditions.What actors can be identified as spoilers? Why? Are theyinadvertent or intentional spoilers?DynamicsWhat are windows of opportunity?eg are there positive developments? What factors supportthem? How can they be strengthened?What scenarios can be developed from the analysis of theconflict profile, causes and actors?eg best case, middle case and worst case scenarios.Note: This list is not exhaustive and the examples may differaccording to the context.What are current conflict trends?What are windows of opportunity?What scenarios can be developed from the analysis of theconflict profile, causes and actors?3.Working with indicatorsIn addition to traditional (eg project, sectoral) indicators,conflict sensitive approaches require conflict sensitiveindicators to monitor and measure: (a) the context and itschanges over time; and (b) the interaction between thecontext and the intervention. They have three elements:5

6Conflict-sensitive approaches to development, humanitarian assistance and peace building:tools for peace and conflict impact assessment Chapter 2lConflict indicatorsUsed to monitor the progression of conflict factors againstan appropriate baseline, and to provide targets againstwhich to set contingency planning (see below).lProject indicatorsMonitor the efficiency, effectiveness, impact andsustainability of the project (see Chapter 3 Module 1, step3).lInteraction indicatorsMeasure the interaction between the context and theproject (see Chapter 3 Module 1, step 2c).analysis will have looked at the relationship between specificactors, causes and profile, in order to gain an understandingof the conflict dynamics. Indicators can then be developed inorder to reflect these relationships and how they evolve overtime. It is important to have a mix of perception-based andobjective indicators, each of which should reflect qualitativeand quantitative elements. Good indicators reflect a variety ofperspectives on the context. It is good practice to involvecommunities and other actors in identifying the indicators;not only should this produce better indicators but it is also animportant opportunity to build a common understanding ofthe context, to ascertain joint priorities and to agree onbenchmarks of progress.Conflict indicatorsConflict analysis provides just a snap-shot of a highly fluidsituation. It is therefore important to combine an in-depthanalysis with more dynamic and continuous forms ofmonitoring to provide up-to-date information from which tomeasure the interaction between the context and theintervention. Indicators are useful in this respect, as they helpreduce a complex reality to a few concrete dimensions andrepresent valuable pointers to monitor change. The conflictSince each conflict is unique, there is no standard list ofindicators applicable to all contexts. The following tableprovides some examples of sample perception-based andobjective indicators for the four key elements.TABLE 1Sample of conflict analysis indicatorsKey elementExampleSample Indicators (a)objective and (b)perception-basedProfileGeographic mobilisation around naturalresources(a) What is the price of timber? How has itevolved over time?(b) (In the view of the respondent) Howhas conflict intensity changed around thisparticular area?CausesHuman rights abuses(a) Has the number of political prisonersrisen or fallen?(b) To what extent can you/others openlycriticise the government?ActorsDiaspora(a) Have overseas remittances increasedor decreased?(b) To what extent does the diasporasupport or undermine the peace process?DynamicsIncreased commitment to resolve conflict(a) Has the frequency of negotiationsincreased or decreased among conflictparties?(b) Do you believe that party X iscommitted to the peace process?Note: the examples in Table 1 relate to each specific key element only (eg sample indicators for profile have no relation to theexample or sample indicators for causes).

Conflict-sensitive approaches to development, humanitarian assistance and peace building:tools for peace and conflict impact assessment Chapter 24.Integrating conflictanalysis and other formsof assessmentAt all levels, humanitarian, development andpeacebuilding organisations use some form ofpre-intervention assessment of the context in which theyoperate in order to identify entry points and plan theirwork. This is usually called a needs assessment.Needs assessment frameworks, such as sustainablelivelihoods assessments, participatory povertyassessments, participatory rural appraisals, goodgovernance assessments and gender analyses can usefullybe complemented by conflict analyses, and vice versa asexplained below:lassumptions about context: livelihood, poverty andgovernance frameworks assume static situations andtherefore provide little guidance on how to deal withchanging and fluid contexts. Conflict analysis thus helpsto better understand these environmentslfocus: livelihood and poverty assessments take theindividual household as a starting point, seeking toestablish the economic, political, social and culturalfactors affecting the lives and livelihoods of itsmembers. This perspective is a valuable addition to the“top-down” view of conflict analysis. In practice,however, these approaches often describe rather thanexplain poverty and tend to neglect issues of politicsand power. There is little scope, for example, forexploring competition and exploitation. There alsotends to be a lack of attention to the implications ofweak political systems, bad governance and instabilityfor households’ livelihood strategies. Governanceassessment frameworks deal with these issues, too, butusually under the assumption of peaceful politicalcompetition and willingness to reform. Theseassumptions might be questioned by a conflict analysis(see section 2.5)lexternal / internal view: poverty and otherparticipatory forms of assessment help understandpeople’s individual perspectives and experience. Theseare often missing from conflict analysis, which tends toplace more emphasis on the interests and strategies oforganised political actors. Not infrequently, conflictanalyses are conducted from an outside perspective.It is important to recognise the distinct frameworksunderlying conflict analysis and other forms of needsassessment. In practice, however, there is a growing effortand acknowledged need to carry out an integratedresearch and analytical process that takes account of bothperspectives. The following table provides somepreliminary entry points for integrating conflict analysisinto needs assessments.TABLE 2Entry points for integrating conflict analysis intoneeds assessmentlBeyond describing poverty, focus on its potential causes,examine the impact of power and powerlessness onpoverty and establish the sources of power in theparticular community.lRefine the understanding of group membership andgroup identity and how they affect vulnerability (egpersecution, exploitation).lExamine how the wider conflict dynamics impact oninstitutions and relations within the community,understand processes of dominance, alignment andexclusion.lLink local processes (eg displacement) to political andeconomic interests and strategies at regional andnational levels (eg land appropriation, war economy).5.Good practice in conflictanalysisThe following section addresses key concerns in relation toundertaking conflict analysis, as the conflict-analysisprocess itself needs to be conflict sensitive. This sectionoffers examples of good practice based on consultations inKenya, Uganda and Sri Lanka.Building capacity for conflict analysisConducting conflict analysis requires human and financialresources, which organisations may find hard to afford,especially if conflict sensitivity has not yet become amainstreamed policy within the organisation (see Chapter5). As a result, this may require systematically andsustainably building the need for conflict analysis intofunding applications (for civil society organisations),budgets, planning guidelines, and human andorganisational development plans. According to the levelof awareness and capacity in your organisation, capacitybuilding for conflict analysis may involve:lhelping staff to better understand the context in whichthey work. For example, in post-conflict contexts, staff7

8Conflict-sensitive approaches to development, humanitarian assistance and peace building:tools for peace and conflict impact assessment Chapter 2of international organisations often do not recognisethe links between their work and possible violence.Local government or civil society staff, on the otherhand, may be too involved at the micro level to see thelarger picturellmaking sure organisations give conflict analyses andtheir integration equal priority to other forms ofassessment (governance, poverty, needs assessments,etc) (see Section 4)wherever possible, integrating conflict analyses intoestablished procedures (eg strategic plans, needsassessments, etc), as well as into the contributions ofservice providers (eg terms of reference for short-termadvisors, calls for proposals / tenders, etc). Whenpreparing such processes, it is fundamental to makesufficient time to accommodate conflict analyseslbudgeting for conflict analysis in funding applicationsand operational budgets. Donors (and the tax payers towhom donors are accountable) may need to besensitised to the importance of conflict analysis. NGOsoften find that donors either (a) assume or even requirethat conflict analysis be conducted at the projectproposal stage, without being aware of its costs forsmaller organisations; or (b) do not prioritise conflictanalysis at alllsupporting staff in acquiring conflict analysis skills onan ongoing basis, for example through staffdevelopment plansldeveloping an external network of national andinternational experts on which to draw for specifictasks.Who conducts the analysis?Conflict analysis can be undertaken for various purposes. Thepurpose will determine the specific process and will help todetermine who should conduct the analysis. For example, ifthe purpose is to promote a participatory and transformativeprocess within a community, the community should play avital role in the planning, implementation (eg data collection)and assessment of the analysis. If the purpose is to develop astrategy for engagement in a given context, it may be that aninternal team from within the organisation developing thestrategy should lead the process. Some elements of theanalysis may be highly sensitive, and thus may need to beconfidential.Local project staff typically conduct participatory conflictanalysis exercises with communities to decide on furtherproject activities. Conflict analysis, in the context ofproject monitoring by international NGOs, is frequentlycarried out by national and international staff, sometimeswith the support of an external adviser. Donors tend tocommission external experts or specialised institutes intheir own countries for countrywide conflict analysisstudies, while governments may have dedicateddepartments to deal with specific conflict issues. In anycase, it is important to get the right mix of skills andbackgrounds, which can be summarised as follows:lgood conflict analysis skillslgood knowledge of the context and related historylsensitivity to the local contextllocal language skillslsectoral / technical expertise as requiredlsufficient status / credibility to see throughrecommendationslgood knowledge of the organisations involvedlrepresentation of different perspectives within thecontext under considerationlmoderation skills, team work, possibly counsellinglfacilitation skills.The quality and relevance of the analysis mainly dependson the people involved. These include the person or teamconducting the analysis, on the one hand, and otherconflict actors, on the other. Conflict analysis consists ofeliciting the views of the different groups and placingthem into a larger analytical framework. The quality of theanalysis will depend on how faithfully it reflects the viewsreceived – views may be distorted or given too much or toolittle weight during the filtering process, eitherinadvertently or deliberately. It will also be influenced byhow the team is perceived by various actors within thecontext. For example, if the team is trusted by all actors,they are likely to get more and better information than ifthey are perceived to be too close to certain parties.Every conflict analysis is highly political, and bias is aconstant concern. It may be difficult to be objective, aspersonal sympathies develop and make it difficult tomaintain an unbiased approach. Even a “fly-in” expert willbe influenced by his / her values, previous knowledge ofthe country, the perspectives of his or her employer, andthe people s / he is working with. It may therefore be moreproductive to spell out one’s own position andpreconceptions and be clear about the conditions andrestrictions under which the conflict analysis takes place.The collective basis of the conflict analysis team may alsoensure higher levels of objectivity and impartiality.Selecting the appropriate framework for conflict analysisWhen planning to use a specific framework to supportconflict analysis, it is worth considering its strengths andweaknesses.In general, organisations may find that tools do notnecessarily offer new information, particularly if they havealready developed strong linkages to institutions andcommunities in the area under consideration. Their mainvalue lies in guiding the systematic search for thisinformation and providing a framework for analysing it,thus prompting critical questions and offering newperspectives. Tools can also enhance internal

Conflict-sensitive approaches to development, humanitarian assistance and peace building:tools for peace and conflict impact assessment Chapter 2communication about conflict within an organisation, egbetween provinces and the capital, or between field officesand headquarters. Similarly, conflict analysis tools canguide consultation with a range of communities and otherstakeholders. Finally, international actors appreciate thatstandardised tools ensure a certai

organisations towards a better understanding of the context in which they work, and a conflict sensitive approach. Contents 1. What is conflict analysis and why is it important? 2. Key elements of conflict analysis 3. Working with indicators 4. Integrating conflict analysis and other forms of assessment 5. Better practice in conflict analysis 6.