Transcription

TRAINING OF TRAINERSMANUALCONFLICT TRANSFORMATION AND PEACEBUILDING INRWANDAJUNE 2008This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency forInternational Development. It was prepared by ARD, Inc. and the Center for Justice andPeacebuilding.

PREFACEThe purpose of the Rwanda Land Dispute Management Project (LDMP) is to support and strengthen localresolution of land disputes. This effort is particularly appropriate now because the Government of Rwanda(GoR) is piloting a process for formalizing land rights, with the goal of eventually formalizing land rightsnationwide. LMDP is a USAID-sponsored effort under the Office of Conflict Management and Mitigation. TheLDMP is being implemented in two pilot areas with four main activities:1.2.3.4.Assess land disputes and existing resolution processes in the pilot areas;Develop/refine land-related dispute resolution processes;Build local capacity for land dispute resolution; andConduct a public information and awareness campaign in the pilot areas on land rights andmechanisms that support peaceful reconciliation of land-related disputes.This report is an outcome of Activity 3: a training-of-trainers manual on conflict resolution theory andmethods.This activity was designed to train individuals who are responsible for resolving land disputes at the cell leveland below on dispute resolution methods and on land-related legislation. To conduct these local trainingsessions, a TOT was held to teach the staff of the Rwanda Initiative for Sustainable Development (RISD)about these two topics.A post-conflict reconciliation specialist from the Center for Justice and Peacebuilding prepared and presentedthe five-day conflict/dispute resolution training, which took place from October 29 to November 2, 2007 inKigali. A Rwandan conflict specialist assisted in that training to provide Rwandan-specific expertise.This TOT activity enabled RISD to develop and present a curriculum on basic dispute resolution methods tothe local dispute resolution actors in the two pilot cells: (1) Kabushinge Cell, Rwaza Sector, Musanze District;and (2) Nyamugali Cell, Gatsata Sector, Gasabo District. Details on the local training can be found in aseparate deliverable: “Field Training Report: Training Local Bodies in Kabushinge and Nyamugali Cells on LandDispute Management and Land-Related Laws” (June 2008).ARD, Inc. of Burlington, Vermont, USA is implementing the LDMP, with a grant from USAID’s Office ofConflict Management and Mitigation, Contract No. 696-A-00-07-00006-00. ARD’s partners are the RwandanInitiative for Sustainable Development (RISD), the Rural Development Institute (RDI), and the Center forJustice and Peacebuilding (CJP) at Eastern Mennonite University. ARD and its partners work hand-in-handwith the Rwandan Ministry of Natural Resources (MINIRENA).Authors: Babu Ayindo and Janice Jenner from the Center for Justice and Peacebuilding.ARD Contact:Olga Segars, Project Manager159 Bank Street, Suite 300Burlington, VT 05401Tel: (802) 658-3890Fax: (802) 658-4247Email: osegars@ardinc.comCover Photo: Courtesy of Deborah Espinosa, RDI

TRAINING OF TRAINERSMANUALCONFLICT TRANSFORMATION ANDPEACEBUILDING IN RWANDADISCLAIMERThe author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United StatesAgency for International Development or the United States Government.

CONTENTSAcronyms. iiIntroduction . 1PART 1: Understanding Conflict. 21.1 The Nature of Conflict. 21.2 Functions of Conflict. 31.3 Causes of Disputes and Conflicts . 41.4 African Indigenous Traditions and Culture: Learning from ourExperience. 51.5 Conflict Analysis. 61.6 Tools for Conflict Analysis . 71.7. Power . 81.8. Another Way of Analyzing Conflict: The DSC Triangle: SummaryNotes on the Transcend Method . 9PART 2: Intervening Conflicts .112.1. Conflict Resolution: Terms and Definitions.122.2 Spectrum of Response to Conflict .132.3 Roles Played in Conflict Situations .142.4 Cultural aspects influencing conflict resolution.15PART 3: Mediation .173.1 Active Listening .173.1.1 Objectives of active listening.173.2 Fundamental Elements of Mediation .183.2.1 Stage 1: Introduction.183.2.2 Stage 2: Description .193.2.3 Stage 3: Problem-solving .193.2.4 Stage 4: Agreement .21PART 4: Preparing a training.244.1 Learning Cycle .254.1.1 Retention .264.2 Key Steps in Training Design .264.3 Working Definitions .27Appendix A. Resources for Deeper Understanding .29A.1 Power (Section 1.7).29A.1.1 Problems with the definition of power .29A.2 DSC Triangle: Transcendence (Section 1.8) .30A.3 Part 2: Intervening in Conflict.31A.3.1 Maire Dugan’s Conflict Foci .31A.3.2 Matrix of Conflict Progression .33A.3.3 Three basic and frequent mistakes in conflict practice .34A.4 Part 3: Mediation.34A.4.1 Negotiation.34A.4.2 Mediation - Stage 2: Description.36A.4.3 Mediation - Stage 3: problem solving.37Appendix B. Bibliography.40TRAINING OF TRAINERS MANUAL: CONFLICT TRANSFORMATION AND PEACEBUILDING IN RWANDAi

ACRONYMSCJPCenter for Justice and Peace BuildingCMMConflict Management and MitigationDFIDUK Department for International DevelopmentGORGovernment of RwandaLDMPLand Dispute Management ProjectMINIRENARwandan Ministry of Natural Resources (formerly MINITRE)RDIRural Development InstituteRISDRwanda Initiative for Sustainable DevelopmentTOTTraining of TrainersUSAIDUnited States Agency for International DevelopmentiiTRAINING OF TRAINERS MANUAL: CONFLICT TRANSFORMATION AND PEACEBUILDING IN RWANDA

INTRODUCTIONIntercommunal conflict occurs when actual and perceived incompatibilities result in hostile violent action.What differentiates a conflict from political struggles or peaceful competition is that it involves the potentialof destructive violence. The threat of violence is positively correlated with the willingness of the parties to useviolent means to reach their unilateral and seemingly incompatible goals. However, as much as allincompatibilities do not necessarily lead to destructive violence, all incidents of violence do not lead to theonset of intractable conflict. Thus, incidents of violence alone cannot be seen as sufficient for a seriousconflict to break out and take root.The underlying factors that cause a conflict are usually in place long before the outbreak of violence and it isthe escalation in particular (and the move from political to violent) that turns a situation of peacefulcompetition into a destructive, deadly conflict. In the best of all possible worlds, conflict prevention wouldbe sufficient for preventing any escalation to take place.However, for conflict prevention to be effective, early warning indicatorsmust be detected and addressed before violence becomes too destructive.Preventive measures employed at an early stage need to address thecauses that lie at the root of the conflict. An escalation of violence isoften preceded by a perceived incompatibility of interests betweengroups, asymmetric intergroup power relationships, as well as triggers thatserve to mobilize or rally a group around its grievances.“Peace is not merely theabsence of war but thepresence of justice, of law, oforder—in short, ofgovernment.”– Albert EinsteinSimilarly, de-escalation alone is often not sufficient for a conflict to end.For peace to become sustainable, peacemaking and post-conflict reconstruction activities (peacebuilding andstate building) are often essential to address the underlying causes of a conflict long after the violence hasended and to prevent a conflict from re-erupting.11School of Adv anced International Studies (SAIS), 2005.TRAINING OF TRAINERS MANUAL: CONFLICT TRANSFORMATION AND PEACEBUILDING IN RWANDA1

PART 1: UNDERSTANDINGCONFLICT1.1THE NATURE OF CONFLICT2Conflict is a natural and necessary part of our lives. Whether at home with our families, at work withcolleagues or in negotiations between governments, conflict pervades our relationships. The paradox ofconflict is that it is both the force that can tear relationships apart and the force that binds them together.This dual nature of conflict makes it an important concept to study and understand.Conflict is an inevitable and necessary feature of domestic and international relations. The challengefacing governments is not the elimination of conflict, but rather, how to effectively address conflict when itarises. While most government officials in Africa are not frequently confronted by large-scale violence orhumanitarian crises, they are often involved in lesser but nevertheless serious conflicts over trade, refugees,borders, water, defense, etc. Their government may be party to the conflict or called on to serve as mediator.In either case, they require particular skills and techniques to tackle the issues in a constructive fashion.Conflict can be managed negatively through avoidance at one extreme and the use or threat of force at theother. Alternatively, conflict can be managed positively through negotiation, joint problem solving andconsensus building. These options help build and sustain constructive bi- and multi-lateral relations.Good conflict management is both a science and an art. We have all learned responses to confrontation,threats, anger and unfair treatment. Some of our learned responses are constructive, but others can escalateconflict and raise the level of danger. How we choose to handle a confrontation is largely based upon ourpast experience in dealing with conflict and our confidence in addressing it. One can start to changedestructive responses to conflict by learning to assess the total impact of negative responses and acquiringconfidence in using the tools and techniques of professional peacemakers.Constructive conflict management is as much a science as an art. It is based on a substantial body of theory,skills and techniques developed from decades of experience in international peacekeeping, peacemaking andpeacebuilding. Acquiring a better understanding of the conceptual tools and skills professional conflictmanagers use can help us gain confidence in addressing conflict in a manner which resolves the issues andmaintains or even strengthens relationships. While we may not all go on to become professional peacemakers,these skills and knowledge can help us in any social setting. These tools can help government officials, forexample, address disputes more quickly and effectively, preventing them from growing into domestic orinternational crises.Peace: The distinction is sometimes made between ‘negative peace’ and ‘positive peace’.3 Negative peacerefers to the absence of violence. When, for example, a ceasefire is enacted, a negative peace will ensue. It isnegative because something undesirable stopped happening (e.g., the violence stopped, the oppressionended). Positive peace is filled with positive content such as the restoration of relationships, the creation ofsocial systems that serve the needs of the whole population and the constructive resolution of conflict.Peace does not mean the total absence of any conflict. It means the absence of violence in all its forms and theunfolding of conflict in a constructive way. Peace therefore exists where people are interacting non-violently2Centre for Conflict Resolution, 2001.3See, for example, Galtung, 1996.2TRAINING OF TRAINERS MANUAL: CONFLICT TRANSFORMATION AND PEACEBUILDING IN RWANDA

and are managing their conflict positively—with respectful attention to the legitimate needs and interests ofall concerned.Reconciliation: Reconciliation becomes necessary when negative conflict has occurred and relationshipshave been damaged. Reconciliation is especially important in situations of high interdependence where acomplete physical or emotional barrier between parties in a conflict cannot be maintained. Reconciliationtherefore refers to the restoration of relationships to a level where cooperation and trust become possibleagain. Lederach (1995) stated that reconciliation deals with three specific paradoxes: Reconciliation promotes an encounter between the open expression of the painful past and the search forarticulation of a long-term, interdependent future.Reconciliation provides a place for truth and mercy to meet; where concern for exposing what happenedand letting go in favor of a renewed relationship is validated and embraced.Reconciliation recognizes the need to give time and place to justice and peace, where redressing thewrong is held together with the vision of a common, connected future. Does conflict have to be destructive? We all know how destructive conflict can be. Whether from personalexperience or media accounts, we can all note examples of the negative aspects of conflict. On the otherhand, conflict can have a positive side, one that builds relationships; creates coalitions; fosterscommunication; strengthens institutions; and creates new ideas, rules and laws. These are the functions ofconflict. Our understanding of how conflict can benefit us is an important part of the foundation ofconstructive conflict management.NOTES FOR TRAINERSIt is important to have participants spend some time talking/reflecting about conflict as a basis for futurediscussion in the workshop. An exercise that often works well is to have people come up with many ofthe words that are used for conflict and peace in their language(s) and look at what they mean and/orhow they are used. Another interesting exercise is to look at proverbs or songs that deal with conflictand peace. Pushing people to look at positive aspects of conflict (outlined in the next section) can beimportant, as well as separating “conflict” from “violence.”IMPORTANT: Depending on the language and the culture, it may be very important to spend enoughtime on this to ensure everyone is clear and comfortable with the words used to describe conflict andpeace—some languages/cultures make elaborate verbal distinctions among levels and types of conflict.1.2FUNCTIONS OF CONFLICTWhat positive things have happened to you as a result of conflict? Here are some of the positive aspectsnoted by Coser (1956): Conflict helps establish our identity and independence. Conflicts, especially at earlier stages of yourlife, help you assert your personal identity as separate from the aspirations, beliefs and behaviors of thosearound you. Intensity of conflict demonstrates the closeness and importance of relationships. Intimaterelationships require us to express opposing feelings such as love and anger. The coexistence of theseemotions in a relationship creates sharpness when conflicts arise. While the intensity of emotions canthreaten the relationship, if they are dealt with constructively, they also help us measure the depth andimportance of the relationship.TRAINING OF TRAINERS MANUAL: CONFLICT TRANSFORMATION AND PEACEBUILDING IN RWANDA3

Conflict can build new relationships. At times, conflict brings together people who did not have aprevious relationship. During the process of conflict and its resolution, these parties may find out thatthey have common interests and then work to maintain an ongoing relationship. Conflict can create coalitions. Similar to building relationships, sometimes adversaries come togetherto build coalitions to achieve common goals or fend off a common threat. During the conflict, previousantagonism is suppressed to work toward these greater goals. Conflict serves as a safety-valve mechanism which helps to sustain relationships. Relationshipswhich repress disagreement or conflict grow rigid over time, making them brittle. Exchanges of conflict,at times through the assistance of a third party, allow people to vent pent-up hostility and reduce tensionin a relationship. Conflict helps parties assess each other’s power and can work to redistribute power in a systemof conflict. Because there are few ways to truly measure the power of the other party, conflictssometimes arise to allow parties to assess one another's strength. In cases where there is an imbalance ofpower, a party may seek ways to increase its internal power. This process can often change the nature ofpower within the conflict system. Conflict establishes and maintains group identities. Groups in conflict tend to create clearerboundaries which help members determine who is part of the “in-group” and who is part of the “outgroup”. In this way, conflict can help individuals understand how they are part of a certain group andmobilize them to take action to defend the group’s interests. Conflicts enhance group cohesion through issue and belief clarification. When a group isthreatened, its members pull together in solidarity. As they clarify issues and beliefs, renegades anddissenters are weeded out of the group, creating a more sharply defined ideology on which all membersagree. Conflict creates or modifies rules, norms, laws and institutions. It is through the raising of issuesthat rules, norms, laws and institutions are changed or created. Problems or frustrations left unexpressedresult in the maintaining of the status quo.NOTES FOR TRAINERSWhen working with a group, it often works well for the facilitator to give one or two examples of aconcept you are trying to get across. For example, you might say, “conflict can be positive when it bringsout problems that have been hidden before”—and then use an example from the community thateveryone would know. Then ask that others give examples of ways in their own lives they have seenconflict work positively.1.3CAUSES OF DISPUTES AND CONFLICTSPart of developing an effective intervention strategy is to know the general categories of causes of conflict.One model4 identifies five sources of conflict: 44Data or information conflict involves lack of information and misinformation, as well as differingviews on what data are relevant, the interpretation of that data and how the assessment is performed.See Moore, 1996.TRAINING OF TRAINERS MANUAL: CONFLICT TRANSFORMATION AND PEACEBUILDING IN RWANDA

Relationship conflict results from strong emotions, stereotypes, miscommunication and repetitivenegative behavior. It is this type of conflict which often provides fuel for disputes and can promotedestructive conflict even when the conditions to resolve the other sources of conflict can be met. Value conflict arises over ideological differences or differing standards on evaluation of ideas orbehaviors. The actual or perceived differences in values do not necessarily lead to conflict. It is only whenvalues are imposed on groups, or groups are prevented from upholding their value systems, that conflictarises. Structural conflict is caused by unequal or unfair distributions of power and resources. Timeconstraints, destructive patterns of interaction and non-conducive geographical or environmental factorscontribute to structural conflict. Interest conflict involves actual or perceived competition over interests, such as resources, the way adispute is to be resolved, or perceptions of trust and fairness.An analysis of the different types of conflict the parties are dealing with helps the intervener determinestrategies for effective handling of the disputes.NOTES FOR TRAINERSWhen you are training in the community, it is not necessary for you to try to get participants tounderstand all the nuances of these various concepts—though it is important for you to keep them inmind. It is important as you work with people to keep asking questions that point them toward lookingat the “why” of the conflicts that they are dealing with: “What are the reasons that have caused thenumber of people having problems with land?”1.4AFRICAN INDIGENOUS TRADITIONS AND CULTURE: LEARNINGFROM OUR EXPERIENCE5“I was one of nine children living in a four bedroom house. In ourhouse the movement between the kitchen and the kitchen orbathroom required traffic lights, especially in the mornings. Wewere seven boys with only three pairs of shoes we had tonegotiate at every stage—in the kitchen, in the bathroom—andfor all the scarce resources in the house. We came tounderstand human nature. We learned to be goodnegotiators many of the students we teach come from suchbackgrounds. What happens to them when they come to ourinstitutions? Do we recognize their collective problems solvingskills and utilize for effective teaching and learning, or do weforce them into a mold created for us by Europe?”6Laws and resolution of conflict in African societies is closely related to the whole system of morality andethics of African religion. It is hard to separate “law” in African tradition from custom, taboo, divination,mediumship, ordeals and the expectations of sharing, harmony, play and good company in general. It is alsodifficult to separate resolution of conflict from the structures of family, lineage, clan and the varioussodalities.5Magesa, 1997.6Ntuli, 1999.TRAINING OF TRAINERS MANUAL: CONFLICT TRANSFORMATION AND PEACEBUILDING IN RWANDA5

The African legal system and moral system are inseparable. Punishment or coercion generally takes the formof moral pressure. The person may suffer loss of self-esteem, or be treated with ridicule or contempt.Throughout the court hearing, the judges try to prevent the breaking of relationships, and to make it possiblefor the parties to live together amicably in the future. Judgments are meant to be both conciliatory andtherapeutic. They reeducate the parties and the entire community through a type of social learning broughtabout in a specially structured interpersonal setting.What is central in the judicial process is the act of listening by those whose task is to make the judgmentbetween the litigant and plaintiff. This is usually done at great length, sometimes with details seeminglyirrelevant to the case.The shedding of blood—even enemy blood—is always inauspicious, and is invariably followed by elaboraterituals of purification.What the African religious worldview emphasizes, therefore, are relationships. Through the act of creation,God is related in an unbreakable way to the entire universe. At the center of the universe is humanity, but ittoo is intrinsically and inseparably connected to all living and non-living creation by means of each creature’slife force. Although God, spiritual beings, ancestors, humanity, living things and non-living things enjoy lifeforces with greater and lesser powers, all forces are intertwined. Their purpose ultimately is humanity; theycan act either to increase or suppress the vital force of an individual person or for a community. A conflict resolution/peace process is an opportunity for the education of the whole community.Reconciliation is not just about humans; conflict causes disequilibria within other realms of existence,hence the need for rituals of resolution.In the process of responding to conflict, we must still respect humans by saving their face and avoidembarrassing and/or shaming people.The language of conflict resolution should encourage resolution by avoiding embarrassment and breakingbarriers.Face saving creates the space for self-examination and invites all the parties in conflict to listen to eachother.The process of resolving conflicts should be inclusive. The language was designed to accommodatedifferent levels of meaning so that everyone was included.NOTES FOR TRAINERSThis is an extremely important section for you, the trainers. Conflict transformation and peacebuildingwas not “invented” by the West in the last 30 years; people and cultures around the world have solvedconflicts in culturally appropriate ways since the beginning of time. Your task is to take what is usefulfrom the global community and apply it to the situation in Rwanda. In terms of training in thecommunity, the important thing related to this is to work to instill in people the confidence that theycan solve disputes and conflict using methods and values that make sense in their context, while learningnew insights and skills from the experience of people around the globe.1.5CONFLICT ANALYSISConflict analysis is the process of looking critically at a particular conflict to understand the causes, context,participants, stakeholders and other aspects of the conflict. Too often, people attempt to intervene in aconflict before understanding it, with less than positive results. A thorough conflict analysis provides a basisfor determining interventions that will have increased possibilities of success.6TRAINING OF TRAINERS MANUAL: CONFLICT TRANSFORMATION AND PEACEBUILDING IN RWANDA

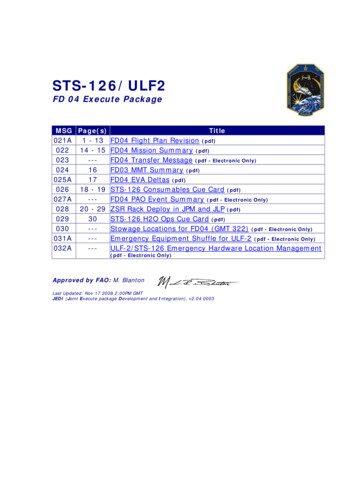

The following questions and dilemmas7 are ones that are useful to consider in a conflict analysis process.1. Who are the parties relevant to the conflict situation?2. What are the positions of each party in the conflict?3. What are the needs and interests of each party? [In other words, what are they saying without saying? What liesbeyond the spoken word?]4. What is the relative power, status and resources of each part in the conflict?5. What are the processes they are using to pursue their interest in conflict with other?6. Within what framework, structure or system is the conflict taking place?7. How are decisions made and conflict resolved/transformed in the situation?8. What external factors impact the conflict?9. What outcome does each party expect?10. What are the possible changes as the result of the resolution/transformation of the conflict at followinglevels:a) Personal,b) Relational,c) Structural/systems,d) culture/traditions, ande) Spiritual.1.6TOOLS FOR CONFLICT ANALYSISPeacebuilding practitioners have developed a number of tools that assist in analyzing conflicts. One of themost useful is conflict mapping, which visually depicts the people, issues and relationships in a conflict. Aconflict map can be used to: Identify all stakeholders Assess stakeholders’ relationships Assess power dynamics Identify and assessalliances Identify and carefully evaluatesome possible entry pointsfor investigation orintervention Assess intervenerrelationships withstakeholders Assess your own positionregarding issues and actors To the right is an example of howto develop a conflict map for aconflict. It is often helpful tobegin with the major parties, andthe major issues, and then add inother parties, issues, andrelationships. Note: “Party” canrefer to individuals or groups.7Party CParty BParty DIssue XParty AIssue YWhereare you?Party EOutside stakeholderParty FWhereare you?Adapted from Duke, 1976.TRAINING OF TRAINERS MANUAL: CONFLICT TRANSFORMATION AND PEACEBUILDING IN RWANDA7

Here is the explanation of the way that symbols are used in making a conflict map.IssueABconnectionABdirection of power or influenceBABAintermittent connectionABalliancebroken relationshipBAdiscordNOTES FOR TRAINERSThe process of figuring out what is really happening in a conflict, what the causes are, who the

peacebuilding. Acquiring a better understanding of the conceptual tools and skills professional conflict managers use can help us gain confidence in addressing conflict in a manner which resolves the issues and maintains or even strengthens relationships. While we may not all g