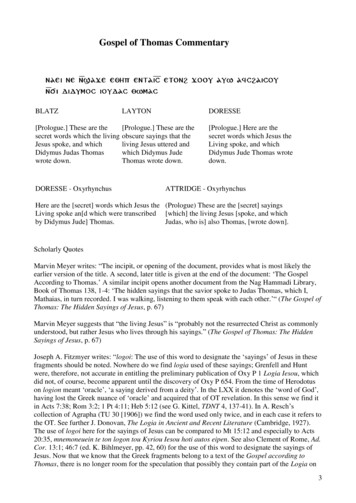

Transcription

Karl KautskyThomas More and hisUtopia(1888)1

Thomas More and his UtopiaKarl KautskyHalaman 2Written: 1888Published: Thomas More and his Utopia was first published in English in 1927by AC Black translated from Thomas More und seine Utopie by Henry JamesStenning. It was republished as a facsimile by Lawrence and Wishart in 1979when out of copyright.Transcribed: Ted Crawford for marxists.org, May, 2002. Note: Some typos inthe original have been corrected.PART ITHE AGE OF HUMANISM AND OF THEREFORMATIONIntroductionChapter I. THE RISE OF CAPITALISM AND OFTHE MODERN STATE1. Feudalism2. The Towns3. World Trade and AbsolutismChapter II. LANDED PROPERTY1. Land Hunger – Feudal and Capitalist2. The Proletariat3. Serfdom and Commodity Production4. The Economic Redundancy of the New Nobility5. The KnighthoodChapter III. THE CHURCH1. The Church in the Middle Ages – its Necessityand Power2. The Basis of the Papacy's Power3. The Overthrow of the Papal PowerChapter IV. HUMANISM1. Paganism and Catholicism2. Paganism and Protestantism3. Scepticism and Superstition

Thomas More and his UtopiaKarl KautskyHalaman 3PART IITHOMAS MOREChapter I. THOMAS MORE’S BIOGRAPHERS1. Roper and Others2. Erasmus of RotterdamChapter II. MORE AS HUMANIST1. More’s Youth2. More as Humanist Writer3. More on Education and the Position of Women4. More’s Relation to Art and ScienceChapter III. MORE AND CATHOLICISM1. More’s Religiosity2. More an Opponent of Clericalism3. Mores Religious ToleranceChapter IV. MORE AS POLITICIAN1. The Political Condition of England at theBeginning of the Sixteenth Century2. More as Monarchist and Opponent of Tyranny3. More as Representative of the LondonMerchants4. The Political Criticism of Utopia5. More Enters the King’s Service6. More’s Contest with Lutheranism7. More in Conflict with the Monarchy8. More’s DownfallPART IIIUTOPIAChapter I. MORE AS ECONOMIST ANDSOCIALIST1. The Roots of More’s Socialism2. The Economic Criticism of Utopia

Thomas More and his UtopiaKarl KautskyHalaman 43. The Economic Tendencies of the Reformationin EnglandChapter II. THE MODE OF PRODUCTION OFTHE UTOPIANS1. Exposition2. CriticismChapter III. THE FAMILIES OF THE UTOPIANS1. Description2. CriticismChapter IV. POLITICS, SCIENCE, AND RELIGIONIN UTOPIA1. Politics2. Science3. ReligionChapter V. THE AIM OF UTOPIAThomas More and His Utopia

Thomas More and his UtopiaKarl KautskyHalaman 5Part I.THE AGE OF HUMANISM AND OFTHE REFORMATION

Thomas More and his UtopiaKarl KautskyHalaman 6INTRODUCTIONTwo great figures loom on the threshold of Socialism:Thomas More and Thomas Münzer, two men whose famerang throughout Europe in their lifetimes: one a statesmanand scholar who attained to the highest position in his nativeland and whose works aroused the admiration of hiscontemporaries; the other an agitator and organiser, beforewhose quickly collected multitudes of proletarians andpeasants the German princes trembled. Fundamentallydifferent from each other in respect of standpoint, method,and temperament, both were alike as regards their object –communism, alike in daring and fidelity to conviction, andalike in the end which overtook them – both died on thescaffold.It is sometimes debated whether the honour of havinginaugurated the history of Socialism should fall to More orto Münzer, both of whom follow the long line of Socialists,from Lycurgus and Pythagorus to Plato, the Gracchi,Catilina, Christ, His apostles and disciples, who aresometimes mentioned in proof of the assertion that therehave always been Socialists without the goal ever comingnearer.We grant that with the development of commodityproduction a class of free persona without property arose inantiquity, who were called by the Romans proletarians. Andin connection therewith endeavours to abolish or alleviatemany social inequalities manifested themselves betimes. Butthe proletariat of old was quite different from the modernvariety, and modern Socialism is equally different fromantique Socialism.

Thomas More and his UtopiaKarl KautskyHalaman 7There are historians who believe they find in the Rome ofJulius Caesar the same proletariat as in modern London,Paris, or Berlin. In reality, however, the modern proletariathas undergone manifold changes during the short space of400 years it has existed, in accordance with concurrenteconomic development. The proletariat of to-day ismarkedly dissimilar from the proletariat of 1848, and muchmore numerous are its variations from its prototype in thedays of Utopia, when Capital had but just entered on itseconomic revolution, and feudalism still wielded anextensive power over the economic life of the masses of thepeople.The new ideas, prompted by the new interests, had notdiscarded the vestments of modes of thinking derived fromfeudalism, and the latter persisted as traditional illusionslong after the main props of its material foundation hadbeen knocked away.The peculiar character of that time would necessarily colourthe socialism which then arose. More was a child of his age;he could not overstep its limits, but it testifies to hisperspicacity, and perhaps also to his instinct, that he alreadyperceived the problems inherent in social development.The bases of his socialism are modern, but they are overlaidby so much that is not modern that it is often extremelydifficult to reveal them. While More’s socialism is at no pointreactionary in its tendency, inasmuch as he did not perceivethe salvation of the world to lie in a return to feudalconditions, it frequently happened that only the resources offeudal times were at his disposal for solving the problemswhich confronted him. Consequently, he had to twist and

Thomas More and his UtopiaKarl KautskyHalaman 8turn them about in a truly fantastic manner to adapt them tohis modern aims.To the student who thoughtlessly examines More’scommunism many of his expedients will appear to bedistorted, bizarre, and arbitrary, but they are, in fact,dictated by a thorough and well-digested knowledge of theneeds and means of his time.Like every other Socialist, More can only be understood inthe light of his age, to comprehend which a knowledge of thebeginnings of capitalism and the decline of feudalism, of thepowerful part played by the Church on the one hand, and ofworld commerce on the other, is necessary. These influenceshad a profound effect upon More, and before we can sketchhis personality and estimate his writings, it is incumbent onus to indicate, at least in outline, the historical situationwhose product he was.That is the task of the first part of our work.

Thomas More and his UtopiaKarl KautskyHalaman 9Chapter I. THE RISE OF CAPITALISM AND OFTHE MODERN STATE1. Feudalism“THE sciences are flourishing and minds are active; it is apleasure to be living,” exclaimed Hutten of his time. And hewas right. For joyfully combative spirits like his it was apleasure to live in a century which boldly swept asideancient conditions and inherited prejudices, which impartedfluidity to the inert social development and at one strokeinfinitely extended the horizon of European society, whichcreated new classes and released new ideas and struggles.As a “Knight of the Spirit” Hutten had every reason to rejoicein his time. As a member of the Order of Chivalry he mighthave regarded it with less favourable eyes. The fate of hisclass was linked with that of the oppressed. Its alternative toextinction was to seek in servitude to a prince the livelihoodwhich the soil refused to yield it.The keynote of the sixteenth century is the death--grapple offeudalism with nascent capitalism. It bears the impress ofboth modes of production, and constitutes a strange mixtureof the two.The foundation of feudalism was peasant and handicraftproduction within the limits of the local community.One or more villages formed a local community, withcommon property in woods, meadows, and water, originallyin arable land too. Within this local community the wholeprocess of medieval production went on. The commonproperty in land, as well as the transmitted private property

Thomas More and his UtopiaKarl KautskyHalaman 10in fields and gardens, supplied the requisite means of life,the products of the cultivation of the fields, of cattle rearing,of hunting and fishing, and the raw materials which wereworked up within the patriarchal peasant family or by thehandicraftsmen of the village – wood, wool, etc.Both private and public activity within this communityaimed at supplying articles of use for consumption by theproducer or his family or his community, or sometimes bythe feudal lord.A local community was an economic organism which wasusually self-sufficing and had almost no economic contactwith the outside world. This led to a remarkableexclusiveness. He who did not belong to the community wasaccounted a stranger, devoid of rights or possessing veryfew, even when he settled in the community, so long as hedid not acquire a holding of land. The whole world outsidethe community was foreign. The members of the communitydeveloped, on the one hand, aristocratic pride towardsnewcomers from the world without, who were unable toacquire any landed property, and, on the other hand, thatlocal narrowness, that parochial policy which may still beseen in remote and backward countries. Upon suchfoundations were based the particularism and the separationof castes peculiar to the feudal Middle Ages.The economic ties of the feudal State were thereforeextremely loose. Empires were rapidly formed and as rapidlyfell to pieces. Even the national language did not form a tieof importance, as the exclusiveness of the local communitiesfavoured the formation and maintenance of dialects.

Thomas More and his UtopiaKarl KautskyHalaman 11The only strong organisation which stood above the localcommunities was the universal Catholic Church, with heruniversal language, Latin, and her universal landedproperty. She it was who held together the entire mass ofsmall, self-sufficing organisms of production in WesternEurope.The power of the Chief of State, of the King, was as slight asthe ties of the State were loose. From the State itself themonarchy could derive but little power. It drew its strength,like every other social force of the time, from its landedproperty. The greater the landed property of a feudal lord,the more peasants in a community, the more communitiesin the country owing him fealty, the greater were his meansof life, the greater in extent and variety were the personalservices at his disposal; the larger and more splendid wasthe castle he could build, the more numerous were thehandicraftsmen and artificers he could maintain at hisCourt, who supplied him with clothing, utensils, ornaments,and weapons; the larger was his travelling retinue, the moresumptuous his hospitality, the more vassals he could attachto himself.The king was usually the largest landowner in the country,and therefore the most powerful. But he was not strongenough to impose subjection on the other landowners. Whenunited they were generally stronger than he, while thegreatest among them was a formidable opponent. The kinghad to rest content with being recognised as the first amongequals. His position became increasingly precarious asfeudality developed, as the power of the feudal lords grew bythe subjugation of free peasants, as the area from which a

Thomas More and his UtopiaKarl KautskyHalaman 12militia could be raised contracted, leaving the kingdependent on an army of chivalry.The national and local princely power generally began onlyto raise its head again when the towns were sufficientlyconsolidated to afford it a firm support.2. The TownsThe local community formed the basis of the medievaltownship as well as of the village. It was commerce,especially with Italy, which gave the impulse to itsdevelopment. This commerce had never quite stopped afterthe downfall of the Roman Empire, even at the time of thegreatest convulsions. The peasants, at any rate, did notrequire it, as they produced themselves what they needed.But the squires, the higher nobility, the higher clergy createda demand for the products of a higher industry. The artisansattached to their courts could only partially satisfy this need.They were not capable of producing fine linen, ornaments,and the like, such as Italy supplied. From time to time theGerman nobles procured these treasures during pilgrimagesto Rome; but by the side of this a systematic commerce wasgrowing up, which was especially sustained in Germany afterthe tenth century by the silver mining in the Hart district.The silver mines of Goslar began to be worked in 950.At the courts of the secular lords, at the seats of the bishops,and at certain trade junctures, as where the roads from theAlpine passes touched the Rhine or the Danube, at protectedplaces in the interior of the country, which were accessible tolarge ships, such as Paris and London, depots for thewarehousing of goods soon came into existence, which,

Thomas More and his UtopiaKarl KautskyHalaman 13insignificant as they may seem to us to-day, yet aroused thecovetousness of the surrounding inhabitants and of foreignrobbers, Normans, Hungarians, etc. It became necessary tofortify them. Thus a start was given to the development ofthe town from a village.But even after the building of walls, agriculture andproduction for consumption within the limits of the localcommune remained the chief occupation of the inhabitantsof the fortified place. The commerce was too insignificant toalter its character. The town burghers remained as locallynarrow and exclusive as the village peasants.By the side of the old fully privileged families of the villagecommunity there arose in the meantime a new power, thatof the artisans, who organised themselves in associations, inguilds, after the example of the commune.Handicraft was not originally commodity production. Theartisan stood in a certain relation of service either to thelocal commune, or, as a retainer, to a feudal lord. Heproduced for the needs of the local commune or of the Courtto which he was attached, not for sale. Such artisans were, ofcourse, very numerous in the towns, especially such as werethe seats of bishops or the landed nobility. Other artisanswere attracted as trade developed, and a market for theproducts of industry was opened. The artisan was now nolonger obliged to work under a servile relationship. He couldbecome a free producer of commodities. The servile artisansin the towns endeavoured to shake off their obligations, andthose in the environs fled to the town when they thought itwould protect them.

Thomas More and his UtopiaKarl KautskyHalaman 14Handicraft grew apace; but it remained for the most partexcluded from the local commune and consequently fromthe government of the town; the latter being reserved for thedescendants of the original members of the villagecommunity, who developed from peasant communists intohaughty patricians. A class struggle between the guilds andthe old families set in, which generally ended with thecomplete victory of the former. At the same time a strugglewas going on to procure the independence of the town fromthe overlordship of the landed or provincial nobility, andthis independence was often achieved.In these struggles with the land-owning aristocracy thehandicraftsmen felt a certain sympathy with the peasants,who were striving for an alleviation of their feudal burdens.Not infrequently both classes acted together. A democraticand republican tendency among the lower burghers wasfostered by these struggles, but it did not entirely abolish theearlier exclusiveness of the village community, which wasmerely extended to the guild and the municipality.Handicraft commodity production at least broke down theexclusiveness of the urban community; the artisans workednot merely for the town, but also for the surroundingdistrict, often serving an extensive area; not so much for thepeasants, who continued to make for themselves almost allthey needed, as for their exploiters, the feudal lords, whohad lost the artisans attached to them. On the other hand,the artisans drew their means of life and raw materials fromthe country. The economic interactions, as well as theantagonism, between town and country began. By the side ofthe village community the town, with a larger or smallervicinage, tended to increase in importance as a second

Thomas More and his UtopiaKarl KautskyHalaman 15economic unit. The segregation of the individual towns,persisted, however, despite their permanent or temporaryassociation for common ends. The effect of this was toweaken, rather than strengthen, political cohesion, as therich and proud city republic achieved an independencewhich would have been quite impossible for the villagecommunities. They formed, by the side of the great feudallords, a new occasion for political disruption.With the aid of the towns, the power of the squires wasdirected against the nobility. Eventually, however, they werethreatened with the fate of being completely destroyed bytheir former allies. But this tendency only asserted itself to aslight extent; for within the towns was growing up a newpower which was to turn them into bulwarks of a rigidpolitical absolutism: the revolutionary power of mercantilecapital, which gave rise to world commerce.3. World Trade and AbsolutismAs we already know, the trade between Italy and theTeutonic North had never quite ceased, even after the fall ofthe Roman domination. It had founded the towns. But it wastoo weak, so long as it remained chiefly petty commerce, toimpart to them a special character. For some time to come,agriculture within the confines of the village communities,and later guild handicraft, occupied most of their energiesand determined their character.This was the case with many towns until the last century,and in some instances is even so to-day. But a number oftownships grew into larger towns, and thus became thepioneers of a new social order. Such were the towns which,

Thomas More and his UtopiaKarl KautskyHalaman 16owing to the special favour of historical and geographicalcircumstances, became centres for overseas trade, for worldcommerce.In medieval Europe, the overseas trade with the East firstdeveloped in Lower Italy, in Amalfi, where Greeks andSaracens came into conflict with the natives and afterwardsestablished trading relations with them. Much as the Easthad declined, it was infinitely superior to the West in artisticskill and technical knowledge. Not only had the primevalbranches of production been maintained there, but new oneshad grown up by their side, such as the production andpreparation of silk in the Greek Empire. Moreover, theIslamic migration of peoples had brought the highly civilisedcountries of the Far East, India and China, into much closercontact with Egypt and the seaboard countries of theMediterranean than was the case at the time of the Romandomination.In the eyes of the European barbarians, the treasuresdisplayed by the merchants of Amalfi were valuable beyondcompare. The greed to possess and acquire such treasuressoon seized all the ruling classes in Europe. It powerfullycontributed to those expeditions of plundering and conquestto the East which were known as the Crusades, but it alsoencouraged all the towns situated in a geographicallyfavourable position to participate in such a lucrativecommerce. First and foremost in North Italy.In course of time attempts were made to imitate theproducts of industry which were imported, especiallyweaving. Even in the thirteenth century we find silk-weavingsheds in Palermo, operated by Greek prisoners of war. In the

Thomas More and his UtopiaKarl KautskyHalaman 17fourteenth century similar weaving sheds were establishedin the towns of North Italy.Once the products were successfully imitated, the merchantssoon found it more profitable to import the raw material andhave it worked up at home by hired workers, provided theycould find free workers, workers whom no guild compulsionor feudal service prevented from offering their services, andwhom no ownership of means of production relieved fromthe necessity of selling their labour power.In this way the arts of manufacture arose, and thefoundations of the capitalist mode of production were laid.In More’s time, at the beginning of the sixteenth century,these beginnings were but faintly perceptible, and industrywas still chiefly under the control of guild handicraft. Capitalwas mainly merchant’s capital. But even in this form it wasalready exerting a disintegrating effect upon the feudal modeof production. The more the exchange of commoditiesdeveloped, the greater became the power of money. Moneywas the commodity which everyone took and everyoneneeded, for which one could receive everything, everythingwhich the feudal mode of production offered-personalservices, house and hearth, food and drink – as well asinnumerable articles which could not be produced under thefamily roof, articles the possession of which becameincreasingly necessary and which were not to be obtainedexcept with money. The classes engaged in acquiring money,producing or exchanging, attained to increasing importance.The guildmaster who, owing to the legally restricted numberof his journeymen, could only achieve moderate prosperitywas soon outpaced by the merchant whose appetite for profit

Thomas More and his UtopiaKarl KautskyHalaman 18was boundless, whose capital was capable of unlimitedexpansion, and whose trading profits were enormous.Merchant’s capital is the revolutionary economic force of thefourteenth, fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. It revitalisedsociety and provided men with fresh outlooks.In the Middle Ages we find a narrow particularism, aparochial outlook side by side with a cosmopolitanism whichcomprised the whole of Western Christendom. The feeling ofnationality was therefore very weak.The merchant cannot confine himself to a small district asthe peasant or artisan can. He wants the whole world inwhich to sell his goods. In contrast to the guild citizen, whomay never pass beyond the walls of his town, we find themerchant untiring in his journeys to unknown countries. Hepasses beyond the boundaries of Europe, and inaugurates anepoch of discoveries which culminates in revealing the searoute to India and the discovery of America, and which,strictly speaking, is still going on to-day.Even to-day it is the merchant who gives the impulse to mostvoyages of discovery, and not the scientific investigator. TheVenetian Marco Polo got as far as China even in thethirteenth century. Ten years after Marco Polo, an attemptwas made by daring Genoese to find a sea route to India byway of Africa, an undertaking which was to succeed twocenturies later. Of greater significance for the economicdevelopment was the opening of direct sea communicationfrom Italy to England and Holland, which was effected byGenoese and Venetians towards the end of the thirteenthcentury, and gave a strong impulse to capitalism in thesecountries of the North-West.

Thomas More and his UtopiaKarl KautskyHalaman 19Commerce put in place of local ties a cosmopolitan feelingwhich was at home wherever a profit could be earned. At thesame time it set up nationality against the universality of theChurch. World trade widened the horizon of the Westernpeoples far beyond the region of the Catholic Church, andsimultaneously narrowed it within the sphere of their ownnation.This sounds paradoxical, but it is easy to explain. The small,self-sufficing communities of the Middle Ages were scarcely,if at all, in economic antagonism with each other. Withinthese communities there were indeed antagonisms, but theoutside world was regarded with indifference, provided itdid not disturb the communities. For the great merchant, onthe other hand, it is not a matter of indifference whatrelations the community to which he belongs has to theoutside world. Trading profit arises from buying as cheapand selling as dear as possible. Profits largely depend uponthe relative strength of buyers and sellers. It is, of course,most profitable to find oneself in the pleasant position ofbeing able to take commodities from a commodity ownerwithout giving him any return. In fact, in its beginnings,trade is very often indistinguishable from piracy. We see thisin the Homeric poems, and we shall also see later that in. theEngland of the sixteenth century piracy was a favourite formof the “primitive accumulation” of capital and thereforeenjoyed State support.With trade, however, competition arose among buyers aswell as sellers. In the foreign market these antagonismsbecame national antagonisms. The conflict of interests, forexample, between the Genoese buyers and the Greek sellersin Constantinople, became a national antagonism. On the

Thomas More and his UtopiaKarl KautskyHalaman 20other hand, the conflict of interests between Genoese andVenetian merchants in the same market like-wise became anational antagonism. The stronger Genoa was as comparedboth with Venice and the Greek Empire, the more tradingprivileges it might expect in Constantinople. The greater andmore powerful was the homeland or the nation, the biggerwere the profits.The development of world trade therefore promoted apowerful economic interest, which tightened andconsolidated the loose textures of States, but also broughtabout their separation from each other and dividedChristendom into several sharply sundered nations.After the rise of world-wide commerce home tradecontributed equally to the strengthening of national States.By its nature trade tends to concentrate in certainemporiums, junctions where the roads of a large districtcoalesce. There the goods from abroad are collected, in orderto be distributed over the whole country by means of acomplicated network of roads. At the same junctions thehome commodities were collected in order to be despatchedabroad. The whole district dominated by such an entrepôtbecame an economic organism, whose ties became all thecloser, whose dependence upon the centre all the stronger,the more commodity production developed and supplantedproduction for use.From all parts of the district dominated by this centre peopleflocked thence; some intending to remain there, othersintending to return after the transaction of their business.The centre grew, it became a large town, in which wasconcentrated not only the economic life but also the

Thomas More and his UtopiaKarl KautskyHalaman 21intellectual life of the country which it dominated. Thelanguage of the town became the language of the merchantsand of cultivated persons. It tended to supplant Latin and tobecome the written language. But it also began to supplantthe peasant dialects; a national language came intoexistence.Political administration was adapted to the economicorganisation. This too was centralised, the political centralpower was installed at the centre of the economic life, andthe latter became the capital of the country, which it nowdominated not only economically but also politically.In this way the economic development brought into beingthe modern State, the national state with a homogeneouslanguage, a centralised administration, a capital.This course of development was frequently distorted, but atthe end of the fifteenth and beginning of the sixteenthcenturies its trend may be distinctly perceived in the Statesof Western Europe, and perhaps all the more distinctlybecause at the time feudalism still greatly influenced theeconomic life, and by the force of tradition to a still greaterdegree governed the forms of the intellectual life.Assumptions taken for granted a few generations later hadthen still to assert their “right to existence” and likewise toimpugn the ancient institutions. The new economic,political, and intellectual tendency had to cut a path throughexisting conditions; it had to enter upon controversy, andconsequently its aim was often more sharply defined than inthe following century.It is noteworthy that the trend of development just describedwas bound to favour monarchy, or rather the power of the

Thomas More and his UtopiaKarl KautskyHalaman 22local prince, ill all places where he had preserved a remnantof strength. It was natural that the new political centralpower should cluster round the person of the local prince,and that he should form the head of the centralisedadministration and army. His interests and the interests ofcommerce were the same. The latter needed a reliablecaptain and a strong army, which, in accordance with thecharacter of the economic power whose interests it served,was hired for money. Commerce needed the army to assertits interests both at home and abroad: to defeat competingnations, to conquer markets, to burst the bonds with whichthe small communities inside the State fettered free trade, topolice the roads against the great and small feudal lords,who opposed a bold denial, not always of a theoreticalnature, to the right of property which commerce proclaimed.International intercourse also provided occasions for frictionbetween the various nations. Commercial wars became morefrequent and more violent. But every war increased thepower of the princes and made them more and moreabsolute.In the absence of a traditional princedom which thisdevelopment would have favoured, a frequent result was theabsolutism of the leaders of the mercenary hordes which theStates required, as in various republics of Northern Italy.But the new polity not only needed the prince as supremecaptain. It also needed him as the chief of the politicaladministration. The feudal administrative apparatus was inprocess of dissolution, the bureaucracy was as yet in itsinfancy. Political centralisation, which was an economicnecessity for commodity production at the incipient stage of

Thomas More and his UtopiaKarl KautskyHalaman 23the capitalist mode of production, needed at

Thomas More and his Utopia Karl Kautsky Halaman 3 PART II THOMAS MORE Chapter I. THOMAS MORE’S BIOGRAPHERS 1. Roper and Others 2. Erasmus of Rotterdam Chapter II. MORE AS HUMANIST 1. More’s Youth 2. More as Humanist Writer 3. More on Education and the Position of Women 4. More’s Relation to