Transcription

Notes onIsaiah2 0 2 2 E d i t i o nDr. Thomas L. ConstableTITLE AND WRITERThe title of this book of the Bible, as is true of the other prophetical books,comes from its writer. The book claims to have come from Isaiah's hand(1:1; 2:1; 7:3; 13:1; 20:2; 37:2, 6, 21; 38:1, 4, 21; 39:3, 5, 8), and JesusChrist and the apostles quoted him as being the writer at least 21 times,more often than they quoted all the other writing prophets combined.There are also many more quotations and allusions to Isaiah in the NewTestament without reference to Isaiah being the writer. Kenneth Hannawrote that there are more than 400 quotations from or allusions to theBook of Isaiah in the New Testament.1 J. A. Alexander noted that 47 of the66 chapters of Isaiah are either quoted or alluded to in the New Testament,and that the 21 quotations attributed directly to Isaiah were drawn fromchapters 1, 6, 8, 9, 10, 11, 29, 40, 42, 53, 61, and 65.2 The only OldTestament book referred to more frequently than Isaiah in the NewTestament is Psalms.The name of Isaiah, the son of Amoz, is the only one connected with theauthorship of the book in any of the Hebrew manuscripts or ancientversions. Josephus, the Jewish historian who wrote at the end of the firstcentury A.D., believed that Isaiah wrote this book. He said that Cyrus readthe prophecies that Isaiah had written about him and wished to fulfill them.3Josephus' statement is not necessarily true—it has been shown thatJosephus made some historical errors—but his statement does show thatJosephus believed that Isaiah wrote this book.1KennethG. Hanna, From Moses to Malachi, p. 346.A. Alexander, Commentary on the Prophecies of Isaiah, 1:13.3Flavius Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews, 11:1:1-2.2J.Copyright Ó 2022 by Thomas L. Constable

2Dr. Constable's Notes on Isaiah2022 EditionIsaiah lived in Jerusalem, and that capital city features prominently in hisprophecies. Isaiah referred to Jerusalem by using more than 30 names. Hiseasy access to the court and Judah's kings, revealed in his book, suggeststhat he ministered to the kings of Judah and may have had royal blood inhis veins. Jewish tradition made him the cousin of King Uzziah. Hiscommunication gifts and his political connections, whatever those mayhave been, gave him an opportunity to reach the whole nation of Judah.The prophet was married and had at least two sons, to whom he gavesignificant names that summarized major themes of his prophecies (8:18):Shearjashub ("A Remnant Shall Return," 7:3), and Maher-shalal-hash-baz("Hastening to the Spoil," 8:3). Hosea's children also received names withprophetic significance.Isaiah received his call to prophetic ministry in the year that King Uzziahdied (740 B.C.; 6:1). He responded enthusiastically to this privilege, eventhough he knew from the outset that his ministry would prove relativelyfruitless and discouraging (6:9-13). His wife was a prophetess (8:3),probably in the sense that she was married to a prophet; we have no recordthat she prophesied herself. Isaiah also may have trained a group ofdisciples who gathered around him.1 His vision of God, which he received atthe beginning of his ministry, profoundly influenced Isaiah's whole view oflife, as well as his prophecies, as is clear from what he wrote. As Paul'sDamascus road vision of God shaped his theology, so Isaiah's vision of Godshaped his.There is no historical record of Isaiah's death. Jewish tradition held that hesuffered martyrdom under King Manasseh (697-642 B.C.) because of hisprophesying. The early church father Justin Martyr (ca. A.D. 150) wrotethat the Jews sawed him to death with a wooden saw (cf. Heb. 11:37).2Another ancient source says that he took refuge in a hollow tree, but hispersecutors discovered and extracted him. This may account for theunusual method of his execution.3Isaiah was arguably the greatest of four prophets who lived and wrotetoward the end of the eighth century B.C. Amos and Hosea ministered inthe Northern Kingdom of Israel at this time, and Micah and Isaiah served in1Seemy comment on 8:16.also The Martyrdom of Isaiah 5:1ff.3See Appendix 1: "Old Testament Writing Prophets by century B.C.," and Appendix 2: "TheOld Testament Writing Prophets," at the end of these notes for charts.2See

2022 EditionDr. Constable's Notes on Isaiah3Judah. An easy way to remember these four is to remember the phrase "ahmi" made from the first letters of their names. Jonah also prophesied inIsrael in the eighth century (2 Kings 14:25), but the book that bears hisname records his ministry to Nineveh."Beyond all question, Isaiah was the greatest of all the OTprophets, for his thought and doctrine covered as wide a rangeof subjects as did the length of his ministry."1"What Beethoven is in the realm of music, what Shakespeareis in the realm of literature, what Spurgeon was among theVictorian preachers, that is Isaiah among the prophets. As awriter he transcends all his prophet compeers; and it is fittingthat the matchless contribution from his pen should stand asleader to the seventeen prophetical books."2UNITYThere is no record that any serious scholar doubted that Isaiah wrote theentire book before the twelfth century A.D., when Ibn Ezra, a Jewishcommentator, did so. With the rise of rationalism, in the seventeenth andeighteenth centuries, some German scholars took the lead in questioningthat Isaiah wrote all 66 chapters. They claimed that the basis for their newview was the differences in style, content, and emphases in the variousparts of the prophecy. Many scholars have noted that it is not really thetext itself that argues for multiple authorship as much as the presence ofpredictive prophecy in chapters 40—66, which critics who deny anythingsupernatural try to explain away.Many modern rationalistic critics believe the purpose of prophetic literatureis simply to call a particular people to faith in God, not to predict the future.However, if the prophets did not predict the future, their theology isquestionable. They frequently claimed that the fulfillment of theirpredictions would validate their theology, and it did. Six times in Isaiah Godclaimed the ability to predict the future (42:8-9; 44:7-8; 45:1-4, 21;46:10; 48:3-6). The English word "prophecy" comes from the Greekprophemi, which means "to say before (or beforehand)." Before Samuel,1Walter2J.C. Kaiser Jr., Toward an Old Testament Theology, pp. 204-5.Sidlow Baxter, Explore the Book, 2:217.

Dr. Constable's Notes on Isaiah42022 Editionprophets were often called seers, because they could see into the future,with God's help (1 Sam. 9:9). However, the Bible also refers to Abraham,Aaron, Moses, and others as prophets before Samuel's time (Gen. 20:7;Exod. 7:1; Deut. 34:10; et al.).PRIESTS AND PROPHETS IN ISRAELPriestsTheir threefold taskProphetsTheir threefold taskOffer sacrifices for the peopleReceive messages from GodTeach God's Word to the peopleDeliver God's messages to thepeopleLead them in formal worshipLead them in heartfelt worshipTeachers of the peopleAppealed primarily to the mindGoal: understanding by thepeoplePreachers to the peopleAppealed primarily to theemotions and willGoal: obedience by the peopleInherited their ministryWere called by God to theirministryDidn't foretell the futureForetold the future occasionallyLived in assigned towns ideallyLived anywhereWere very numerousWere not as numerousCame from one tribe and familyCame from any tribe or familyWere males onlyWere males and femalesLater were divided by "courses"Later lived in "schools"Were gifts from God to the peopleWere gifts from God to the people

2022 EditionDr. Constable's Notes on IsaiahKINDS OF5PROPHETSSolitary prophets (e.g., Abraham, Moses, Elijah)Worship leaders (e.g., Miriam, the 70 Israelite elders, Saul, David)Court prophets (e.g., Nathan, Gad)Preaching prophets (e.g., Ahijah, Isaiah, Jeremiah)Writing prophets (e.g., Moses, David, Isaiah, Hosea)Form critics have distinguished three basic types of prophetic oracles ormessages from God. These are: oracles of judgment (e.g., most of the Bookof Nahum), oracles of repentance (e.g., much of the Book of Jeremiah),and oracles of salvation (e.g., the Abrahamic and Davidic Covenants).Someone has said that "prophecy is the mold into which history is poured."At first, rationalistic critics of the Book of Isaiah hypothesized that therespective emphases on judgment in chapters 1—39 and consolation inchapters 40—66 pointed to two separate writers: Isaiah and "DeuteroIsaiah." With further study, a theory of three writers ("Trito-Isaiah")emerged because of the differences between chapters 40—55 and 56—66.1 These critics believed that there are addresses to three differentaudiences in three different historical settings by three different individualsin these three parts of the book: during Isaiah's lifetime (ca. 739-701 B.C.;chs. 1—39), during the Babylonian exile (ca. 605-539 B.C.; chs. 40—55),and during the return from exile (ca. 539-400 B.C.; chs. 56—66).2 Manymodern commentators, including some otherwise conservative scholars,still hold this three-writer hypothesis."Along with what is known as the JEDP theory of the origins ofthe Pentateuch, the belief in the multiple authorship of the1See,for example, Gerhard von Rad, Old Testament Theology, 2:295.Eugene H. Merrill, "Survey of a Century of Studies on Isaiah 40—55," BibliothecaSacra 144:573 (January-March 1987):24-43; idem, "Literary Genres in Isaiah 40—55,"Bibliotheca Sacra 144:574 (April-June 1987):144-55.2See

Dr. Constable's Notes on Isaiah62022 Editionbook of Isaiah is one of the most generally accepted dogmasof biblical higher criticism today."1One can make a strong case for Isaiah writing chapters 1—39 in preparationfor the exile, chapters 40—55 as though he were in exile, and chapters56—66 as though he were living after the exile. But that does not meanthat three different writers wrote these sections.Here is a chart of how "normative" biblical criticism dates Isaiah and someother Old Testament books:2EpochLiteraturePre-exilic (760-586 B.C.)EarlyAmosHoseaFirst Isaiah (chs. 1—35)MicahPsalms of Zion (Pss. 46, 48, and 87)LateJeremiahExilic (586-539 B.C.)EarlyJeremiahDeuteronomist (Deuteronomy—2 Kings)EzekielLateSecond Isaiah (chs. 40—55)Post-exilic (516—?350 B.C.)1JohnN. Oswalt, The Book of Isaiah, Chapters 1—39, p. 17. One modern commentator onIsaiah who advocated this approach is John D. W. Watts.2Adapted from Bruce K. Waltke, "Micah," in Obadiah, Jonah, Micah, p. 170.

2022 EditionEarlyDr. Constable's Notes on Isaiah7ZechariahHaggaiThird Isaiah (chs. 56—66)Ezra-NehemiahLateMalachiJoelBefore the Dead Sea Scrolls were discovered in 1947, the oldest Hebrewmanuscripts of the Old Testament that were known were produced in theninth century A.D.1 The reason that so few older copies of these Biblebooks existed is that the Jews normally "retired" old copies of theirScriptures, placed them in a "genizah" (a repository for sacred writings),and eventually burned them. One of the Dead Sea Scrolls is the so-calledSt. Mark's [or Monastery] manuscript of Isaiah."The St. Mark's manuscript of Isaiah is the only one of thescrolls that contains a whole book of the Bible, and, with theexception of some of the small fragments [of othermanuscripts that were discovered], it is the oldest of themanuscripts found in the caves."2Millar Burrows dated this manuscript of Isaiah "from a little before 100 B.C.,or possibly a little later."3 This shows that the Book of Isaiah was at thattime a unified document. This does not prove single authorship, but it lendsweight to the argument of conservative scholars that one person wrotethe entire book.Internal and external evidence points to the unity of authorship. The titlefor God, "Holy One of Israel," which reflects the deep impression thatIsaiah's vision in chapter 6 made on him, occurs 12 times in chapters 1—39 and 14 times in chapters 40—66, but only seven times elsewhere inthe entire Old Testament. Other key phrases, passages, words, themes,1MillarBurrows, The Dead Sea Scrolls, p. 302.p. 303.3Ibid., p. 118.2Ibid.,

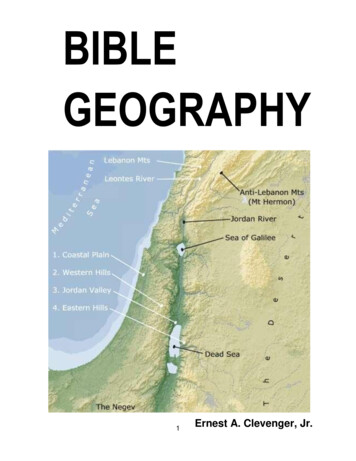

8Dr. Constable's Notes on Isaiah2022 Editionand motifs likewise appear in both parts of the book.1 Jewish traditionuniformly attributed the entire book to Isaiah, as did Christian tradition untilthe eighteenth century. The St. Mark's manuscript of Isaiah has chapter 40beginning in the same column in which chapter 39 ends.2 All the majorcommentaries and introductions deal with the unity problem.3HISTORICAL BACKGROUND AND DATEIsaiah ministered during the reigns of four Judean kings (1:1): Uzziah (792740 B.C.), Jotham (750-732 B.C.), Ahaz (735-715 B.C.), and Hezekiah(715-686 B.C.).4 The prophet began his ministry in the year that KingUzziah (or Azariah) died, namely, 740 or 739 B.C. (6:1).5During Uzziah's reign, Judah enjoyed peace because of her surroundingnations' lack of antagonism and hostility. However, in 745 B.C. Tiglathpileser III mounted the throne of Assyria and began to expand his empire.His three successors (Shalmaneser V, Sargon II, and Sennacherib) provedequally ambitious. Aram (Syria) and Israel (Ephraim) felt the pressure ofAssyrian expansion before Judah did, because they were closer to Assyriageographically. But in King Ahaz's reign, Judah had to make a crucialdecision regarding her relationship to Assyria. Isaiah played a major role inthat decision (ch. 7).A second major crisis arose during the reign of King Hezekiah. By this timeBabylon had defeated Assyria, and it was also expanding aggressively inJudah's direction. Again Isaiah played a major part in the decision abouthow Judah would respond to this threat (chs. 36—39).1SeeOswalt, pp. 17-23.T. Allis, The Unity of Isaiah, A Study in Prophecy; p. 40. For a photograph of thissection of Isaiah 39 and 40 in the Isaiah scroll, see figure 17 in Joseph P. Free's,Archaeology and Bible History.3See also Allis, pp. 39-50; Tremper Longman III and Raymond B. Dillard, An Introductionto the Old Testament, pp. 303-11; Baxter, 2:219-36; Gleason L. Archer, Encyclopedia ofBible Difficulties, pp. 263-66.4Edwin R. Thiele, A Chronology of the Hebrew Kings, p. 75. See 2 Kings 15:1-7, 32-38;16:1-20; 18—20; and 2 Chron. 26-32 for the biblical accounts of these kings' reigns.5See Appendix 3: "Dates of the Rulers of Judah and Israel," at the end of these notes fora chart.2O.

2022 EditionDr. Constable's Notes on Isaiah9" Isaiah exercised his prophetic ministry at a time of uniquesignificance, a time in which it was of utmost importance torealize that salvation could not be obtained by reliance uponman but only from God Himself. For Israel it was the central orpivotal point of history between Moses and Christ. The oldworld was passing and an entirely new order of things wasbeginning to make its appearance. Where would Israel stand inthat new world? Would she be the true theocracy, the light tolighten the Gentiles, or would she fall into the shadow byturning for help to the nations which were about her?"1Sennacherib outlived Hezekiah, who died in 686 B.C., and Isaiah recordedthe death of Sennacherib in 681 B.C. (37:38). Just how long the prophetministered after that event is impossible to determine, but he must haveprophesied for at least 60 years. However, the bulk of the material in hisbook derives from the first 50 of those years (ca. 740-690 B.C.).Isaiah had a very broad appreciation of the political situation in which helived. He demonstrated awareness of all the nations around his homeland.Judah and Jerusalem were the focal points of his prophecies, but he sawGod's will for them down the corridors of time, as well as in his own day.He saw that the kingdom that God would establish through His futureMessiah would include all people. He was a true patriot who denounced evilsin his land, as well as giving credit where that was due. He condemnedreligious cults yet remained neutral politically.IMPORTANT DATES FOR ISAIAHYearsEvents745Tiglath-pileser III of Assyria begins his reign740Uzziah of Judah dies; Isaiah begins his ministry735Ahaz of Judah begins his co-regency with Jotham; Pekah ofIsrael and Rezin of Aram ally against Assyria733-32 Tiglath-pileser invades Aram and Israel1EdwardJ. Young, The Book of Isaiah, 1:4-5.

Dr. Constable's Notes on Isaiah102022 Edition732Damascus falls; Pekah and Rezin die; Jotham dies727Tiglath-pileser dies722Samaria falls; Shalmaneser V of Assyria dies and Sargon IIbegins to reign715Ahaz dies and Hezekiah begins his reign711Sargon attacks Ashdod and returns to Assyria710Sargon attacks Babylon705Sargon dies701Sennacherib of Assyria defeats Egypt at Eltekah and departsfrom Jerusalem; Merodach-baladan of Babylon sendsmessengers to visit Hezekiah697Manasseh of Judah begins his co-regency690Tirhakah of Egypt begins his reign689Sennacherib of Assyria defeats Babylon686Hezekiah dies681Sennacherib of Assyria dies and Esarhaddon begins to reign671Esarhaddon imports foreigners into Israel and defeats Egypt612Nineveh falls to Babylon609Nabopolassar of Babylon defeats Assyria and Assyria falls605Nebuchadnezzar of Babylon defeats Egypt at Carchemish; firstdeportation of Judahites to Babylon597Second deportation of Judahites to Babylon586Jerusalem falls to Nebuchadnezzar559Cyrus II of Persia begins to reign

2022 EditionDr. Constable's Notes on Isaiah539Cyrus overthrows Babylon538Cyrus issues his decree allowing Jews to return to Palestine530Cyrus dies518Darius Hystaspes of Persia destroys Babylon11AUDIENCE AND PURPOSEIsaiah ministered and wrote to the people of Jerusalem and Judah (1:1).His task was to explain to these Chosen People that the old world orderwas passing away and that the new order—controlled by Gentile worldempires that sought to swallow Judah up—required a new commitment forIsrael to trust and obey Yahweh as His "servant" nation. The Assyrian threatcalled for this new dedication. This was a theological—even more than ahistorical and political—crisis for Judah. It raised many questions that Isaiahaddressed."Is God truly the Sovereign of history if the godless nations arestronger than God's nation? Does might make right? What isthe role of God's people in the world? Does divine judgmentmean divine rejection? What is the nature of trust? What is thefuture of the Davidic monarchy? Are not the idols strongerthan God and therefore superior to him?"1The far-reaching nature of these questions called for reference to thefuture, which Isaiah revealed from the LORD (Yahweh). The NorthernKingdom had made the wrong commitment, but the Southern Kingdom stillhad an opportunity to trust Yahweh and live."Stated briefly, the purpose of Isaiah is to display God's gloryand holiness through His judgment of sin and His deliveranceand blessing of a righteous remnant."21Oswalt,2Charlesp. 28.H. Dyer, in The Old Testament Explorer, p. 527.

Dr. Constable's Notes on Isaiah122022 EditionTHEOLOGYIsaiah's understanding of theology was profound. He set forth the wonderand grandeur of Yahweh more ably than any other biblical writer. As awriter, Isaiah is without a peer among the Old Testament prophets. He wasa poetic artist who employed a large vocabulary and many literary devicesto express his thoughts beautifully and powerfully. Most of his propheciesappear to have been messages that he delivered, so he was probably alsoa powerful orator.The Book of Isaiah (1,292 verses), the fourth longest book in the Bible—after Psalms (2,461 verses), Genesis (1,533 verses), and Jeremiah (1,364verses)—deals with as broad a range of theology as any book in the OldTestament.1 In this respect it is similar to Romans. However, there are fourprimary doctrines, all arising out of the prophet's personal experience withGod in his call (ch. 6) that receive the most emphasis. These are: God, manand the world, sin, and redemption.Isaiah presented God as great, transcendently separate, authoritative,omnipotent, majestic, holy, and morally and ethically perfect. In contrast,he described sarcastically the stupidity of idolatry. God creates history aswell as the cosmos, and He has a special relationship with Israel among thenations. The adjective "holy" (Heb. qadosh) describes God 33 times inIsaiah, but only 26 times in the rest of the Old Testament. Holiness is theprimary attribute of God that this prophet stressed.Isaiah showed the tremendous value that God places on humanity and theworld, but also the folly of pride and unbelief. Assuming pretensions tosignificance leads to insignificance for the creature, but giving truesignificance to the Creator results in glory for humanity and the world. Asall the other eighth-century prophets, Isaiah condemned injustice.Sin is rebellion, for Isaiah, that springs from pride. The book begins andends on this note (1:2; 66:24). All the evil in the world results from man'srefusal to accept Yahweh's Lordship. The prophet repeatedly showed howfoolish such rebellion is. It not only affects man himself but also hisenvironment. God's response to sin is judgment, if people continue to rebelagainst Him, but He responds with redemption if they abandon self-trust1Kaiser,p. 204. See also Longman and Dillard, pp. 312-17.

2022 EditionDr. Constable's Notes on Isaiah13and depend on Him. Sin calls for repentance, and forgiveness for thepenitent is available.God's judgment, the outworking of the personal rage of offended deity,takes many forms: natural disaster, military defeat, and disease being afew, but they all come from God's hand ultimately. The means of salvationcan only be through God's activity. Substitutionary atonement makespossible God's announcement of pardon and redemption. This redemptioncomes through the promised Messiah ultimately, the LORD's anointed King.The goal of redemption is not just deliverance from sin's guilt but thesharing of God's character and fellowship. Salvation could only come toGod's people as they accepted the role of servant. Deliverance cannotcome to man through his own effort, but he must look to God alone for it.His emphasis on salvation has earned Isaiah the title of "evangelist of theOld Testament." One writer called the fifty-third chapter "the fifthGospel."1 Isaiah's name, "The LORD (Yahweh) is salvation," meaning the LORDis the source of salvation, summarizes his message." in that one name is compressed the whole contents of thebook!"2Isaiah is also strongly eschatological (the study of end times events). Inmany passages the prophet dealt with the future destiny of Israel and theGentiles. He wrote more than any other prophet of the great kingdom intowhich the Israelites would enter under Messiah's rule."We stand precisely on 56:1, looking back to the work of theServant (now fulfilled in the person, life, death and resurrectionof the Lord Jesus) and looking forward to the coming of theAnointed Conqueror."3Isaiah's emphasis on the coming Messiah (God's anointed Savior) is secondonly to the Psalms in the Old Testament in terms of its fullness and variety.God revealed more about the coming Messiah to Isaiah than He did to anyother Old Testament character. Messianic themes in Isaiah include: thebranch, the stone (refuge), light, child, king, and especially servant.4 In1DavidBaron, The Servant of Jehovah, p. 3.C. Jennings, Studies in Isaiah, p. 15.3J. Alec Motyer, The Prophecy of Isaiah, p. 33.4For a summary of messianic prophecies in Isaiah, see Arno C. Gaebelein, The AnnotatedBible, 2:2:159-67, or Hanna, p. 364.2F.

Dr. Constable's Notes on Isaiah142022 Editionsome of the passages in Isaiah, Israel is the servant of the LORD that is inview, in others he is Cyrus, in others the faithful remnant in Israel is theservant, and in still others a future individual, the Messiah, is in view. AsMatthew clarified, Jesus Christ was the fulfillment of what God intended theIsraelites to be (Matt. 2:15; cf. Hos. 11:1-2)."It would be difficult to overstate the importance of Isaiah forthe Christology of the church."1"What is the overarching theme of OT theology? Perhaps it isthe covenant. Here in Isaiah, God's special relationship withIsrael is presupposed throughout. Perhaps it is the kingdom ofGod. The whole structure of the book brings out theimplications of God's sovereign control of things in theinterests of his kingdom. Perhaps it is promise and fulfillment.Here we see time and again the word of divine authority beingfulfilled and further fulfillment thereby pledged. Perhaps it issimply God himself, Israel's Holy One. This book is one longexposition of the implications—for Israel and the world—ofwho and what he is. So this great prophecy—its wholestructure unified by its teaching about the Holy One of Israel,who is true to his word, faithful to his covenant, and pursuesthe establishment of his kingdom—is a classic disclosure of thevery heart of the OT faith."2"The theological message of the book may be summarized asfollows: The Lord will fulfill His ideal for Israel by purifying Hispeople through judgment and then restoring them to arenewed covenantal relationship. He will establish Jerusalem(Zion) as the center of His worldwide kingdom and reconcileonce hostile nations to Himself."3In a larger sense, all of the prophets in Israel had as their basic messagethe two commandments that Jesus said were the greatest of all: to love1Longmanand Dillard, p. 319.W. Grogan, "Isaiah," in Isaiah-Ezekiel, vol. 6 of The Expositor's BibleCommentary, pp. 21-22.3Robert B. Chisholm Jr., "A Theology of Isaiah," in A Biblical Theology of the OldTestament, p. 305.2Geoffrey

2022 EditionDr. Constable's Notes on Isaiah15God wholeheartedly, and to love ones neighbor as oneself (Matt. 22:3839; Mark 12:30-31; Luke 10:27)." each generation throughout the First Commonwealth ofIsrael (c. 1050-586 B.C.) was warned about their relationshipGodward and then about their relationship manward. Althoughthe former always had priority in the prophets' preaching, thelatter often received the most extended analysis anddenunciation."1GENRE AND INTERPRETATIONThis book is a compilation of the revelations that Isaiah received from theLORD (Yahweh). He presented this revelation as messages and compiledthem into their present form. His disciples may have put finishing toucheson the collection under divine guidance.Most of the book is poetic in form, the prophet having been lifted up in hisspirit as he beheld and recorded what God revealed to him. Much of thecontent is eschatological and therefore prophetic, though most of theministry of the prophets, including Isaiah, was forth-telling rather thanforetelling. Some of what is eschatological is also apocalyptic, dealing withthe final consummative climax of history in the future. These portions bearthe marks of that type of literature: symbols, analogies, and various figuresof speech. Psalms, Ezekiel, Daniel, Zechariah, and Revelation also containapocalyptic writing.In his commentary on Isaiah 1—39, Marvin Sweeney included a glossary of107 genres that form critics have identified in the Old Testamentprophetical books, plus 17 speech formulas.2 Reputable scholars, however,do not always agree with one another on the genre of a particular pericope(section of text). Sweeney's introduction to the prophetical literature ofthe Old Testament, from a form critical perspective, is helpful thoughtechnical.31SamuelJ. Schultz, "Old Testament Prophets in Today's World," in Interpreting the Wordof God, p. 57.2MarvinA. Sweeney, Isaiah 1—39 with an Introduction to Prophetic Literature, pp. 51247.3Ibid., pp. 10-30.

16Dr. Constable's Notes on Isaiah2022 EditionStudents of Isaiah have difficulty understanding the eschatological portionsof the book. Some believe that we should look for a literal fulfillment ofeverything predicted. Others believe that when Isaiah spoke of Israel andJerusalem he was referring to the church (i.e., all believers throughouthistory). More literal interpretation results in a premillennial (Christ willreturn to earth and then set up a 1,000 rule on the earth) understandingof prophecy, whereas spiritualization (less literal) results in an amillennial(There will be no earthly rule of Christ on the earth in the future) orpostmillennial (The present age is Christ's predicted rule and His return tothe earth will follow) understanding.1The problem with taking every prophecy literally is that in many places theprophet used metaphors and other figures of speech to describe hismeaning; what he wrote does not describe exactly what he meant.2 Theproblem with spiritualizing all the prophecies, the other extreme, is that itrequires reinterpreting the identity of "Israel" as "all the people of God."The New Testament teaches that Israel will have a future in God's plans—as Israel (Rom. 11:26-27). The church, which began on the day ofPentecost, will not replace Israel, though the church does participate insome of the blessing promised to Israel. The most satisfying position, forme, is to interpret Isaiah as literally as seems legitimate in view of otherdivine revelation, while at the same time remembering that some of whatappears to be literal description, may in fact be metaphorical. This is theapproach taken by most premillennialists."The fundamental principle of interpretation of all writings,sacred or profane, is that words are to be understood in theirhistorical sense; that is, in the sense in which it can behistorically proved that they were used by their authors andintended to be understood by those to whom they wereaddressed. The object of language is the communication ofthought. Unless words are taken in the sense in which thosewho employ them know they will be understood, they fail oftheir design. The sacred writings being the words of God toman, we are bound to take them in the sense in which those1SeeJ. Dwight Pentecost, Things to Come, pp. 45-64; Bernard Ramm, Protestant BiblicalInterpretation, pp. 220-53; Roy B. Zuck, Basic Bible Interpretation, pp. 227—49; Paul L.Tan, The Interpretation of Prophecy; for help in interpreting the prophetic genre.2See Ap

his ministry, profoundly influenced Isaiah's whole view of life as well as his 1See Oswalt, pp. 17-23. 2O. T. Allis, The Unity of Isaiah, A Study in Prophecy; p. 40. For a photograph of this section of Isaiah 39 and