Transcription

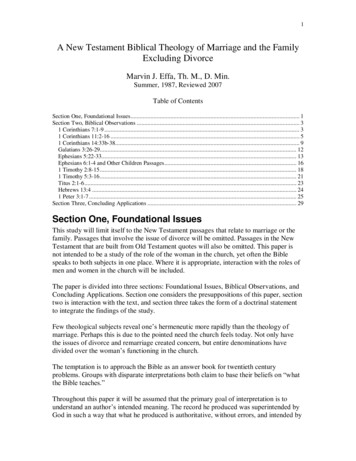

THE THEOLOGY OF THE BOOK OFISAIAH, by John Goldingay. DownersGrove: Intervarsity, 2014. Pp. 160. 18.00(paper).John Goldingay (David Allan Hubbard Professor of Old Testament, Fuller TheologicalSeminary) is one of the most distinguishedIsaiah scholars of his generation. Not only hashe written several major academic and theological commentaries on Isaiah, but he hasalso consistently demonstrated a deep concern for the church and for theological interpretation. Ultimately, I hope to convince thereader that The Theology of the Book of Isaiahcan be used with great benefit in a number ofChristian settings.The Theology of the Book of Isaiah is a highlyaccessible, relatively short (149 pages) volumethat provides the reader with an excellent introductory guide to the book of Isaiah. Andwhen venturing into the literary world of Isaiah, a guide is precisely what is needed, because reading prophetic books is rarely evereasy. Goldingay quotes from Martin Luther:the prophets “have a queer way of talking, likepeople who, instead of proceeding in an orderly manner, ramble off from one thing to thenext, so that you cannot make head or tail ofthem” (11). Goldingay attempts to honor thebook’s complexity, while at the same timecommunicating the book’s main theologicalcommitments. His goals are as follows: “Myaim in this book is, first, to articulate the theology in the book called Isaiah—that is, to consider the theology expressed or implied by thedifferent sections of Isaiah. I then aim to articulate the theology of the book called Isaiah as a86whole, the theology that can be constructedfrom the book when one stands back and considers the whole” (11). Isaiah, like many biblical books, was stitched together over hundredsof years in response to numerous crises, victories, and circumstances, and the result of theseprocesses is a literary work that memorializesnumerous and sometimes conflicting voices.The book is divided into two parts: part 1,The Theologies in Isaiah, and part 2, The Theology That Emerges from Isaiah. While thesecond title is a bit clunky and not entirely descriptive of the contents, it nonetheless reflectsGoldingay’s stated aim, to deal with Isaiah as awitness to multiple theologies and then to dealwith Isaiah as a whole.Part 1 is divided into 5 chapters, which correspond to the literary divisions of Isaiah: Isaiah 1–12, 13–27, 28–39, 40–55, and 56–66.Goldingay refers to each of these units as “collages” (12), each of which is united by similarthemes, generic profiles, or content. The individual chapters in part 1 are expository essaysthat illuminate important theological and literary themes. For instance, chapter 1 coversIsaiah 1–12, which Goldingay divides intosubunits, often three to four pages in length:Isa 1:1–5:30 (“Faithfulness in the Exercise ofPower”), Isa 6:1–9:7 (“Holiness”), Isaiah 7(“Trust”), etc. In accordance with his statedgoals, Goldingay treats each of these collagesmore or less independently, allowing theirdistinct theological voices to emerge.Goldingay does pay some attention to thehistorical circumstances that gave rise to thebook of Isaiah’s five “collages” (see pp. 14–16). But he does this in a way that is clear, con-Copyright 2016 by Word & World, Luther Seminary, Saint Paul, Minnesota. All rights reserved

Reviewscise, and unintimidating. He makes referenceto important interpretive figures such asAbraham Ibn Ezra and Bernhard Duhm, butwithout lingering over unnecessary and cumbersome details.Part 2 (“The Theology that Emerges fromIsaiah”) attempts to analyze the book of Isaiahfrom a more holistic perspective, asking thequestion, “What theology emerges from thisbook as a whole?” (89) To that end, Goldingayisolates twelve themes, which function as separate chapters: Revelation, The God of Israelthe Holy One, Holy and Upright and Merciful,Israel and Judah, Jerusalem and Zion Chastised and Restored, The Remains, The Empiresand Their Kings, Divine Sovereignty and Human Responsibility, Divine Planning and Human Planning, David, Yahweh’s Day. Spacedoes not allow for a detailed discussion of eachchapter, but a sample of one chapter mayprove useful to the reader.Part 2, chapter 1 is titled, “Revelation:Words from Yahweh Mediated throughHuman Agents” (91–96). Revelation is a veryimportant idea in the book of Isaiah, and indeed in Christian theology more generally.From the outset, the book of Isaiah claims to berevelatory (“The vision of Isaiah ben Amoz,”Isa 1:1, emphasis mine), and Goldingay takesthis claim seriously. To claim that Isaiah is revelatory is to assume that it is not “somethingthat the prophet thought up but somethingthat presented itself to him. He did not devisethe words; they came to him” (91). But forGoldingay, revelation does not override human agency; revelation happens “via the human person” (92), and includes that person’sspecific “angle of vision.” Revelation even includes Isaiah’s interpretations of what heheard/saw (92–93). These two ideas—humaninterpretation and divine revelation—are notmutually exclusive. For the leader hoping touse Goldingay’s book as part of a study orTRANSLATING THE REFORMATION:Mar n ther a a toral Theologian or To ayFEB.1-3ηLSconǀoϮϬϭϲKeynote Speakers:Mary Jane Haemig, Professor of Church,ŝsƚorLJ ĂŶĚ ŝrecƚor of ƚhe ZeforŵĂƟoŶResearch Program, Luther SeminaryRobert Kolb, /nternaƟonaů Research meritusProfessor for /nsƟtute for Dission StuĚies,Concordia SeminaryRonal K Ri ger , Professor of History anddheoůogy, saůƉaraiso hniǀersity2016 Mid-WinterCONVOCATIONLL1001-16dTimothy Wengert, meritus Dinisteriumof Pennsyůǀania Professor of ReformaƟonHistory and the Lutheran Confessions,Lutheran dheoůogicaů Seminary at PhiůadeůƉhiawww.luthersem.edu/convo2481 Como Ave. St. Paul, Minn.87

Word & World 36/1 Winter 2016class, his understanding of revelation wouldmake for fascinating and fruitful conversation.This book could be useful for Christians in anumber of ways. For the pastor or ministryleader preparing a talk or sermon on Isaiah,Goldingay will provide broad-stroke and expert commentary on the larger units of thebook. Goldingay’s work, however, is less usefulif one is looking for information on specificpassages. The book excels at overview, but isweak at detailed commentary. Where this volume would shine is in a weekly Bible study, oras a congregational supplement to a sermonseries on the book of Isaiah, perhaps duringAdvent when a significant number of Isaianicpassages emerge in the lectionary. At 149pages and roughly 15, the book is manageable, accessible, and affordable.Michael ChanLuther SeminarySaint Paul, MinnesotaHANGING ON BY A PROMISE: THEHIDDEN GOD IN THE THEOLOGYOF OSWALD BAYER, by Joshua C.Miller. Eugene, OR: Pickwick Publications,2015. Pp. 354 xix. 32.80 (paper).Though a central aspect of Martin Luther’stheology—described most prominently in hisBondage of the Will—Luther’s doctrine of thehidden God has received mixed reception inthe history of doctrine since the sixteenth century, with few theologians choosing to adoptLuther’s view of divine hiddenness. OswaldBayer is a notable exception to this, having actually integrated Luther’s view of the hiddenGod into his own theology. In this comprehensive and probing analysis, Joshua Miller hasproduced a detailed examination of the doctrine of divine hiddenness in Bayer’s theology.After providing initial remarks aboutBayer’s life and work, Miller contextualizes hisstudy in terms of Luther’s own doctrine of thehidden God, helpfully nuancing the more fa88miliar portrait of Luther’s doctrine, drawn primarily from Bondage of the Will, by exploringother texts in Luther’s corpus and reflectingsystematically on the doctrine’s role in Luther’s broader theological work. Miller’s thirdchapter stands out as an impressive accountof the reception of Luther’s doctrine of thehidden God. According to Miller’s analysis,Luther’s doctrine of the hidden God has remained substantially misunderstood in thehistory of Protestant theology, with only a fewexceptions. Moreover, even while some theologians have noted Luther’s doctrine with approval, few have ever incorporated it as anessential component of their own theologies.It is here that Miller commences his sustained engagement with Bayer. Because it isMiller’s thesis that Bayer not only presents anaccurate representation of Luther’s understanding of the hidden God, but that he alsomakes it a prominent feature of his own theology, Miller provides helpful remarks aboutBayer’s theological method. Most importanthere is that Bayer views theology as irreduciblyconnected to the theologian’s experience inoratio, meditatio, and tentatio, and thereforewith the God who encounters us both in theword as well as apart from it.Proceeding on this basis, Miller approachesthe question of the hidden God in Bayer’s theology from four angles. The first is a detaileddescription of Bayer’s understanding of justification by God’s word of promise. By justifying sinners through a performative speech act,God encounters the sinner in his or her creatureliness and makes him or her a new creation thereby. This reality not only forms theprocedural center of Bayer’s theology, but isthe contradictory counterpoint to God’s operation apart from the word in divine hiddenness.Before exploring this contradiction between the justifying word of promise andGod’s terrifying, mysterious operation apartfrom that word, Miller investigates how thehidden God fits with Bayer’s theological

ReviewsComing Soon fromBAKER ACADEMIC978-0-8010-3087-1 304 pp. 29.99pCOMING APRIL 2016Craig Bartholomew and Heath Thomasbring together a team of specialists toarticulate a multifaceted vision for returning rigorous biblical interpretation tothe context of the church. This book isdesigned to bring clarity and unity to theenterprise of theological interpretation.978-0-8010-9545-0 224 pp. 24.99cCOMING MARCH 2016Francis Watson, widely regarded as oneof the foremost New Testament scholarsof our time, explains that the fourGospels were chosen to give a portraitof Jesus. Interweaving historical,exegetical, and theological perspectives,this book is accessibly written forstudents and pastors but is also ofinterest to professors and scholars.ubakeracademic.comAvailable in bookstores or by calling 800.877.2665Visit our blog: blog.bakeracademic.com89

Word & World 36/1 Winter 2016method. This is important because Bayermaintains that God’s speech act justifying sinners in the preached word is not the only datum that informs the doing of theology.Indeed, the theologian’s experience of God’shiddenness also, according to Miller’s interpretation, factors prominently into Bayer’sunderstanding of how theology is done.Since the word of promise in justificationcontradicts the experience of God’s hiddenness, Miller provides helpful elucidation ofhow Bayer understands the hidden God in relation to justification. Ultimately, according toMiller’s exposition of Bayer, the believer musttake refuge in this word of promise even whileits disclosure of God’s mercy and grace inChrist contradicts God’s wrath and mysteryapart from the word. Nevertheless, Miller connects this to Bayer’s theology of lament, inwhich believers cry out to God in light of thetension between the word and God’s operationapart from it. The only resolution of this tension is eschatological, in which God bringsabout the full renewal and restoration of allcreation. Until then, believers must place theirtrust in the justifying word, as well as God’spromise to answer the cries of those wholament.Finally, Miller launches an evaluation ofBayer’s interpretation of Luther. Since the doctrine of the hidden God in Bayer’s work is notmerely description but appropriation, Millerhelpfully compares and contrasts the respective positions of Luther and Bayer. Even whileBayer advances Luther’s understanding of thehidden God as a part of his own theology,Miller’s comparisons to other modern interpreters reveal a very close proximity betweenBayer and Luther on the question of God’shiddenness. Miller’s closing chapter includesrich reflections on the relevance and applicability of Bayer’s understanding of the hiddenGod in the contemporary context for Lutherans.Overall, this text is an excellent introduction to the doctrine of the hidden God and to90the theology of Oswald Bayer. Especially fascinating and helpful is Miller’s conscientiouscontextualization, which is not only judiciousas scholarship but very helpful for the reader.Another benefit of Miller’s work is the clarityhe provides to contemporary discussions ofthe hidden God, especially in his evaluation ofthe doctrine’s reception by theologians such asKarl Barth, Werner Elert, Eberhard Jüngel, andothers. Most importantly, however, Miller’smeticulous exploration of Bayer’s doctrine ofthe hidden God provides resources for Christians who await the full eschatological renewalof all things in Jesus Christ.John W. HoyumLuther SeminarySaint Paul, MinnesotaTHE POLITICS OF JESÚS,by Miguel A.dela Torre. Lanham, MD: Rowan & Littlefield,2015. Pp. 218. 22.00 (paper).The Politics of Jesús stands as the latest, andmost accessible, entry in Miguel A. de laTorre’s project of doing the work of Christianethics from the margins. De la Torre focusesthis book as a theological biography in the tradition of liberation, tracing the life of Jesústhrough his life on the margins of the RomanEmpire, particularly the history of the holyfamily as refugees and as immigrants seekingsanctuary and asylum. The theological centerof the book is in de la Torre’s proposal that “Jesus” is a Eurocentric phenomenon that waslargely created as a religious justification forracism, colonialism, and most importantly,neoliberalism: “Could it be that the Jesus whosupports ‘the American way’ is in reality ananti-Christ?” (5).The book itself supports this proposal bytracing the narrative of the life of Jesus, andutilizing liberationist philosophy, recreatingJesus by locating the Hispanic Jesús in thebiblical narrative that “resonates with the

ReviewsAt the Altarof Wall StreetThe Rituals, Myths, Theologies,Sacraments, and Mission of the ReligionKnown as the Modern Global EconomyScott W. Gustafson“It is daily becoming more clear that consumer capitalism is not justan economic system. It is a fully developed culture and, as Gustafsonshows in this skillfully researched book, a full-blown religion.Replete with its own rituals, doctrines, sacraments, and theology,Economics has become the most powerful alternative to Christianity,all the more threatening because few people recognize its spiritualpretensions. No one who reads this extraordinary account will beable to think about religion or economics in the same way again.”— Harvey CoxISBN 978-0-8028-7280-7 232 pages paperback 22.00At your bookstore,or call 800-253-7521www.eerdmans.comWm. B. EerdmansPublishing Co.55482140 Oak Industrial Dr NEGrand Rapids, MI 4950591

Word & World 36/1 Winter 2016Latino/a existential experience of disenfranchisement and commits, in solidarity, to walktowards a more just social order” (8). Chapter1 begins with reframing the Lucan birth narrative of Jesús, as well as his parents María andJosé, in an attempt to draw out the narrativesas “anticolonial literature about a native resident displaced by the invading colonialpower” (27). De la Torre draws on the Mexicancelebration of las posadas, which literallymeans the inns, to bring a vivid image in whichthe life-seeking migrations of migrants andradical hospitality of hosts is celebrated. Chapter two continues the narrative, tracing the lifeof Jesús as “a street rat, a barrio kid, a spic fromthe wrong side of the tracks,” in which onewonders “Can anything good come from Nazareth?” (59). De la Torre’s imagery helps notonly to unwind imagery for those of us who inherit Northern European traditions, but alsohelps bring Jesús to bear on our current political climate which is filled with rhetoric aroundimmigrants. It is in this light that de la Torreproposes that the barrio life of Jesús is bestcharacterized by his status as a mestizaje, asone who is bilingual in both language and culture, drawing on the ancient creedal traditionof the two natures of Christ.In chapter 3, de la Torre turns his attentionto the contextual similarities between theeconomies of Jesús’ time and ours, eventuallyleading to a renewed focus in the second half ofthe book towards an old Marxist turn towardspraxis and revolutionary justice. While the critiques of laissez-faire capitalism and CEO paythat de la Torre draws are useful, the overallhelpfulness, and newness, of a turn to Marxistepistemology and soteriology through praxisis much more debatable.Chapter 4, I suspect for many readers, willprovide the most challenge and reflection as dela Torre draws forth his two most interestingand challenging proposals: a theology of hopelessness and Jesús as the holy joderon. De laTorre argues, convincingly, that hope formany Christians in North America functions92as a middle-class opiate, “[soothing] the conscious of the privileged” (138). De la Torre’sinsight is helpful, as one can think of all theplaces where hope functions this way: in hospital rooms, in systems of oppression, and inour own avoidance of places and people thatfeel hopeless. While de la Torre suggests that atheology of hopelessness is the place where implementing justice-based praxis is the centerof its life, it is difficult to see what sort ofsustainability the proposal might have, particularly given the very real and life-sustainingtradition of robust hope in the face of nothingness, in this country through black spirituals,jazz, and the blues.While one can’t help but be troubled withde la Torre’s proposal for a theology of hopelessness, and that seems to be part of the point,it is undoubtedly most powerful when it leavesaside the focus on praxis, and instead pinpoints an underutilized portion of the Christian story: Holy Saturday. De la Torre writes:“Perhaps this is the sad paradox: that hopemight be found after it is crucified and thenmay be resurrected in the shards of life” (139).Finally, in a moment of searing humor andinsight, de la Torre’s idea of Jesús as the holyjoderon, which in Spanish means somethingalong the lines of the holy one who “screwswith,” serves as a sort of closing statement inThe Politics of Jesús. Joder in Spanish, which isa vulgarity, is useful for de la Torre in that itserves to show a Jesus who is able to “screwwith” systems of oppression and those who arereligiously uptight. The idea of Jesús as theholy joderon is a novel turn that might be justwhat Christology needs in this day and age.And it is a proposal that allows a further distinction between a white Jesus, and a Jesús ofblack and brown bodies, something ever moreimportant in these days. And it is in this waythat de la Torre gives his greatest contribution,as a Latino voice, in a white academia and alargely white church—allows for a deep breathfor black and brown lives, a breath that allowsus to ponder the Jesús who messes with op-

Reviewshistory essentials!Atlas of theEuropeanReformationsMartin Luther’sNinety-Five ThesesTIM DOWLEYWith Introduction, Commentary,and Study GuideTIMOTHY J. WENGERT“A fascinating introduction intothe theological background of the—THEODOR DIETERTheses.”Institute of Ecumenical Research9781451482799 150pp pb 15Luther RefractedThe Reformer’s Ecumenical LegacyPIOTR J. MALYSZ andDEREK R. NELSON, editorsSpeaks to the currency that Luther’slife and thought continue to enjoy inWRGD\·V &KULVWLDQ UHÁ HFWLRQ 9781451490381 284pp pb 44Newly built from the ground up.Featuring more than sixty brand newmaps, graphics, and timelines, the atlasis a necessary companion to any studyof the reformation era.9781451499698 160pp pb 24Twenty QuestionsThat ShapedWorld Christian HistoryDEREK COOPERTells the story of Christian history bypresenting the twenty questions (onefor each century!) that shaped theChristian church throughout the world.9781451487718 354pp pb 19The Art of EmpireChristian Art in Its Imperial ContextFruit for the SoulLEE M. JEFFERSONand ROBIN M. JENSEN, editorsLuther on the Lament PsalmsDENNIS NGIENForeword by ROBERT KOLB“Ngien takes us to the heart of Luther’sspirituality.”—TIMOTHY GEORGEBeeson Divinity School9781451485219 373pp pb 29“. . . discussions of ritual, practice, andtheology provide a valuable context.Highly recommended!”—ANNEWIES VAN DEN HOEKHarvard Divinity School9781451487664 368pp pb 44Available wherever books are sold or800-328-4648fortresspress.com93

Word & World 36/1 Winter 2016pression and injustice, brings new life, mustdie and is resurrected once more.Eric WorringerSaint Paul Evangelical LutheranChurchArlington, MassachusettsNUESTRA FE: A LATIN AMERICANCHURCH HISTORY SOURCEBOOK,by Ondina E.and Justo L.Gonzáles.Nashville: Abingdon, 2014. Pp. xv 239. 44.99 (paper).If seminarians (and thus pastors) ever didread much about the history of Christianity inLatin America, it came in a general survey ofthe history of Christianity. Usually this meanssome reference to the sixteenth-century European conquest of Central and South America,and then a jump to the twentieth century, witha quick nod to Liberation theology and perhaps Protestant Pentecostalism in the region.Not much else, really, as though 400 years ofChristianity among hundreds of millions ofChristians can be easily ignored. But with thegrowing influence of Latin American Christianity in North America and around the world(Pope Francis, as an example), it is importantto know more about all the history and theology of this region over the centuries. One problem has been, of course, that not much of thishistory has been translated into English, atleast until now. Thanks to the efforts of Ondinaand Justo Gonzáles, we have a fine volume ofsources to cover over 500 years of Christianityin Latin America.This volume does contain some of the selections one might expect. The famous (or infamous) chronicles of the European conquestof this territory in the sixteenth century andthe subsequent Christianization of the population are included, although the volume alsodoes include the protest of some Europeansagainst the brutality of these campaigns, aswell as the clerical histories that describe the94pre-Columbian religions. The final threechapters (out of nine) focus on the twentiethcentury, with separate chapters on contemporary Protestantism and Roman Catholicism,and a final chapter on recent religious conditions in Latin America. The center of the volume contains several chapters on the growthand development of Christianity in the regionin the seventeenth through the nineteenth centuries, which are really very fascinating; theydescribe how Christianity took hold in LatinAmerica and was transformed into a genuinereligion of the people, all the while the winds ofrevolution, independence, dictatorships, andanticlericalism were blowing through the region.Another factor that is helpful in this volumeis its diversity in kinds of entries. Yes, there arethe important papal pronouncements and records of decisions of synods of bishops, asmight be expected. But for a fuller picture, thisvolume also includes other voices and otherperspectives: the accounts of everyday life andeveryday persons, such as housewives andtravelers, mixed-race proto-saints, and Yankee missionaries. The entries also deal with elements of popular religion, the religion thatthe people made for themselves out of a combination of their original religions and theChristianity that was brought to them. Thiscombination of sources makes the book evenmore interesting, and shows a vibrant andmulti-sided religious life.In short, this book is an interesting andthoughtful read, and one that does a great dealto open up for English-readers an importantarea of the history of Christianity; it is wellworth reading.Mark GranquistLuther SeminarySaint Paul, Minnesota

ReviewsA B I T E- S I Z E D I N T R O D U C T I O NPHILOSOPHY INSEVEN SENTENCESA Small Introduction to a Vast TopicDouglas GroothuisPhilosophy is not a closed club or asecret society. It’s for anyone whothinks big questions are worth talkingabout. In this lively introduction,Douglas Groothuis upacks seven shortyet pivotal sentences from the historyof Western philosophy, including keyideas from Protagoras, Socrates,Aristotle, Augustine, Descartes, Pascaland Kierkegaard.144 pages, paperback,978-0-8308-4093-9, 16.00“Philosophy in Seven Sentences is a breath of fresh air. Too often those ofus who identify as philosophers think of our craft as an exercise in intellectual gamesmanship with its own toolkit and narrow list of ‘problems’with which we are supposed to deal. In this small though powerful book,Groothuis reminds us that when Socrates said that ‘the unexamined life isnot worth living,’ he was doing something much more important than justpublishing a career-making breakthrough in metaethics. He was actuallydoing philosophy.”F R A N CI S J. B ECKW I T H ,Baylor UniversityV i s i t i v p a c a d e m ic . c o m /e x a mc o p y t o r e q u e s t a n e x a m c o p y.800.843.9487ivpacademic.com95

Word & World 36/1 Winter 2016THE SERPENT AND THE LAMB:CRANACH, LUTHER, AND THEMAKING OF THE REFORMATION,by Steven Ozment. New Haven and London:Yale University Press, 2013. Pp. 325. 25.00(paper).Once upon a time it was assumed that Reformation Protestantism was indifferent orhostile to art in the church. Steven Ozment inThe Serpent and the Lamb challenges that assumption. His book advances the thesis thatnot only was there an abundance of art in thechurch, but that much of it was created byLucas Cranach the Elder. (There are more than1000 surviving prints and paintings by Cranach, and many more have been lost.) Cranach,Ozment claims, played an indispensable rolein advancing the cause of the Reformation.Ozment asserts that Cranach (who is not wellknown in America) left a lasting mark on European history and art. “Without him, GermanRenaissance art might well have remained apale imitation of High Italian, and the GermanReformation [might] have died aborning inthe 1520s, so vital was Cranach to both” (7).Martin Luther nailed his theses to the doorat Wittenberg in 1517. Cranach had been wonover to Luther’s thinking in the early 1500s;and he and Luther remained fast friends forthe rest of their lives. Many of Cranach’s paintings illustrated themes and personalities thatgave visual impulse to the spoken and writtenwords of the Reformer. Ozment demonstratesthis double momentum with dozens of illustrations, in black and white and color. It is beyond question that we know what Lutherlooked like at various stages of his life becauseof the many painting and prints that Cranachcreated.One of the most significant works visuallyto summarize and advance the impact of theReformation is The Wittenberg Altarpiece. Notonly is Luther depicted seated with the disciples at the Last Supper, but in the predella ofthis work Luther is dramatically pointing to96the crucified Christ, thus preaching thetheology of the cross. We see a rapt congregation listening to the sermon; and in that gathering we can see Katherine von Bora, Luther’swife, and gray-bearded Cranach, Luther’s bestfriend.Early in their friendship Cranach and Luther each adopted a coat of arms. Cranachwanted his image to survive time and outliveposterity, so he chose a kind of biblical “serpent venom” that saved life as well as took itaway (3). Luther, for his part, developed a coatof arms that depicted a lamb. He wanted asymbol of salvation and redemption, a washing of the sinner in the blood of the self-sacrificial Lamb of God. Luther’s emblem, adopted in1524, antedated his better known seal with thecross in the white rose, which he preferred inand following 1530.Another artist of the Reformation periodwho is still well-known worldwide is AlbrechtDürer. Dürer’s series of the Apocalypse andsuch prints as Melancholia and St. Jerome inHis Study hang in many church libraries andpeoples’ studies today. Ozment points out,however, that Cranach was as well-known asDürer in his time and was a close second inpopularity in northern Europe. Ozment’s account of their close friendship and friendlyrivalry gives a fresh understanding and appreciation of the art and theology of the early sixteenth century. These two geniuses stand outas the artistic Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig oftheir time.In addition to biblical scenes and portraits,Cranach depicted many scenes of nudewomen. Two chapters in Ozments’s book examine this phenomenon. One is tempted to seesome of these luscious images as soft porn; yetthe figures, Ozment assures the reader, realistically depict biblical and mythological figureslike David and Bathsheba, Samson and Delilah, Salome, the Judgment of Paris, Venus,and many others. Such depictions of the human body were intended to be, Ozmentinsists, moral lessons for the viewer, forcing

ReviewsNew fromBAKER ACADEMIC & BRAZOS PRESS978-0-8010-9754-6 352 pp. 45.00c“This is theological reflection of a very high order, whoseappearance in English is warmly to be welcomed.”—JOHN WEBSTER, University of St. Andrews978-1-58743-368-9 224 pp. 17.99p“These statements and their accompanying essays deservea wide and attentive readership. . . . Ecumenical writingdone at a superior level.”—LAWRENCE S. CUNNINGHAM, University of Notre Dame978-0-8010-3088-8 272 pp. 26.00pCOMING APRIL 2016PRAISE FOR THE FIRST EDITION“Christology is profound and insightful. . . . I have nohesitation in recommending it to all students at seminariesand anyone interested in Christianity and theology.”—PAUL CHUNG, Pacific Lutheran Theological Seminary97

Word & World 36/1 Winter 2016self-examination in the light of one’s sinful nature. It was supposed to be morally uplifting tolook at Cranach’s revealing print of Adam andEve and ponder the nature of sin and the fall.Dürer also created a portrayal of a nude Adamand Eve that bea

The Theologies in Isaiah, and part 2, The The-ology That Emerges from Isaiah. While the second title is a bit clunky and not entirely de-scriptiveofthecontents,itnonethelessreflects Goldingay’s stated aim, to deal with Isaiah as a witness to multiple theologies and then to deal with Isaiah