Transcription

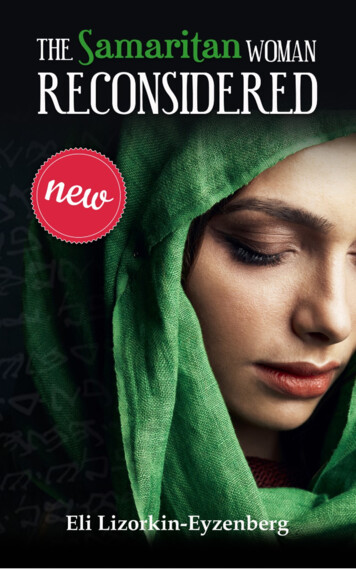

The Samaritan WomanRECONSIDEREDEli Lizorkin-Eyzenberg, Ph.D.JEWISH STUDIESFOR CHRISTIANS2

ISBN: 9781713300366The Samaritan Woman Reconsidered, Copyright 2019 by Eliyahu LizorkinEyzenberg. Illustrations by Lyda Estrada. This book contains material protectedunder International and Federal Copyright Laws and Treaties. Any unauthorizedreprint or use of this material is prohibited. No part of this book may bereproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic ormechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storageand retrieval system without written permission from the author(dr.eli.israel@gmail.com).3

Table of ContentsINTRODUCTION . 7SAMARIA AND SAMARITANS . 9THE ENCOUNTER AT THE WELL. 18REREADING THE SAMARITAN WOMAN STORY . 314

To the Samaritan Woman who heardthe soft sound of sandaled feet.To my friend Marjorie Murraywho also heard the same sound.5

“Our vision is oftenmore abstracted by whatwe think we knowthan by our lack ofknowledge”.Krister Stendahl6

IntroductionThis book is a product of a prolonged personal studyof the Gospel of John. A significant part of what Ishare here in “The Samaritan Woman Reconsidered”was already included in my "The Jewish Gospel ofJohn: Discovering Jesus the King of All Israel” book.While the latter book is a detailed commentary on theentire Gospel of John this book is dedicated to theSamaritan Woman in particular. I decided to supplythis rich Gospel story with additional contextcommentary which was not included in my longerbook and focus exclusively on the fascinatingconversation at the well.This fourth chapter of John’s Gospel, that relates thestory of Jesus meeting the Samaritan woman at Jacob’swell, begins by setting the stage for what will takeplace later in Samaria, and is rooted in what hasalready, by this time in the Gospel’s progress, takenplace in Judea. Jesus’ rapidly growing popularityresulted in a significant following. Jesus’ disciplesperformed an ancient Jewish ritual of ceremonialwashing with water (known to us today as “baptism”),just as John the Baptist and his disciples did. The ritualrepresented people’s confession of sin and their7

recognition of the need for the cleansing power ofGod’s forgiveness. When it became clear to Jesus thatthe crowds were growing large, and especially when heheard that this alarmed the Pharisees, he decided itwas time to go to Galilee through Samaria (verses 1-3).And this is where the story explained it this bookoccurred.The Samaritan Woman is generally portrayed in ourBible studies as a woman of ill-repute. While avoidingpeople because of her deep shame over her immorallife, she seemingly stumbled upon Jesus resting at awell. However, most people reading this story are leftwith a nagging question. How could this woman receivean overwhelmingly positive response from her villageneighbors, when she called them to drop everythingand come with her to meet a Jewish man, she herselfhad just met? Something does not add up.Come with me, reread this story, and let me share withyou what I think really happened.Dr. Eli Lizorkin-Eyzenberg8

Samaria and SamaritansSamaritan lands were sandwiched between Judea andGalilee, though not exclusively. They were situatedwithin the borders of the land allotted to the sons ofJoseph, Ephraim, and Menashe. (Today most Samariaand large parts of Judea constitute thedisputed/occupied territories located in the PalestinianAuthority).Given Judeo-Samaritan tensions, which are similar inmany ways to today’s Israeli-Palestinian conflict, bothgroups tried to avoid passing through each other’sterritories when traveling. The way around Samaria forJudeans traveling to Galilee took twice as long as thethree-day-direct journey from Galilee to Jerusalem,since avoiding Samaria required crossing the riverJordan twice to follow a path running east of the river(Josephus, Life 269). The way through Samaria wasmore dangerous because Samaritan-Jewish passionsoften ran high (Josephus, Antiquities. 20.118 and War2.232). We are not told the reason Jesus and hisdisciples needed to go through Samaria. John simply9

says that Jesus “had to go” 1, implying that, for Jesus,just as it was for all other Jews, this was unusual.1The word “it is necessary” (δεῖ) occurs 10x in John (3:7, 14, 30; 4:4, 20, 24;9:4; 10:16; 12:34; 20:9). Cf. the use of δεῖ in Luke-Acts.10

It is, of course, possible that Jesus needed to reachGalilee relatively quickly. But the text gives us noindication that he had a pending invitation to an eventin Galilee for which he was running late. The text onlystates that he left when he felt an imminentconfrontation with the Pharisees over his popularityamong Israelites was unavoidable. This was coupledwith Jesus’ understanding that the time for such aconfrontation had not yet come.In the mind of Jesus, the confrontation with thereligious powerbrokers of Judea at this time waspremature, and more needed to be done before goingto the Cross and drinking the cup of God’s wrath onbehalf of his people. The way Jesus viewed Samaritansand his own ministry among them may surprise us aswe continue looking into this story.Jesus’ journey through hostile and heretical territoryhas a meaning beyond any surface explanation. In avery real sense, God’s unfathomable plan and mission,from the time His royal Son was eternally conceived inHis mind, was to bind all of his beloved creation inredemptive unity. Jesus was sent to make peacebetween God and man, as well as between man andman. The accomplishment of this grand purposebegan with the mission to unify Samaritan Israeliteswith the Israelites of Judea.I know that this terminology is a little bit unusual, butI will continue to refer to Samaritans as SamaritanIsraelites and to Jews as Judean Israelites because Ibelieve both are Israelites. Though their ways have11

parted a long time ago, their ancient heritage isinseparable. Jesus’ movements and activities were alldone in accordance with his Father’s will and leading.He only did what he saw the Father do (Jn. 5:19). Thisbeing the case, we can be certain that Jesus’ journeythrough Samaria at this time was directed by hisFather, and so too, was his conversation with theSamaritan woman.First, the Samaritan Israelites defined their ownexistence in exclusively Israelite terms. The Samaritanscalled themselves – “the sons of Israel” and “thekeepers” - Shomrim. Jewish sources refer to theSamaritans as Kutim. The term is most likely related toa location in Iraq from which the non-Israelite exileswere imported into Samaria (2 Kings 17:24). The nameKutim or Kutites was used in contrast to the termShomrim which means the “keepers” – the terms thatthey reserved for themselves. Keepers of what? Theold ways, ancient faith, tradition, covenant promises,of course. Jewish Israelite writings emphasized theforeign identity of Samaritan religion and practice incontrast to the true faith of Israel. The SamaritanIsraelites believed that such identification denied theirhistorical right of belonging to the people of Israel.The Samaritan Israelites were the faithful remnant ofthe Northern tribes – the keepers of the ancient faith.Second, Samaritan Israelites had always opposed theworship of Israel’s God in Jerusalem, believing insteadthat the center of Israel’s worship was associated withMt. Gerizim – the mount of YHWH’s covenantalblessing (Deut. 27:12). On the other hand,12

Jewish/Judean Israelites believed Mt. Zion inJerusalem was the epicenter of spiritual activity inIsrael. One of the reasons for the rejection of theprophetic Jewish writings by the Samaritan Israeliteswas that the Hebrew prophets supported Jerusalemand the Davidic dynasty.Third, the Samaritans had a fourfold creed: 1) OneGod – YHWH, 2) One Prophet – Moses, 3) OneBook – Torah, and 4) One place – Mt. Gerizim. MostJewish Israelites of Jesus’ day agreed with theSamaritan Israelites on two of these points: “oneGod” and “one Book”. They disagreed on the identityof the place of worship and on other books thatshould also have been accepted by the people of Israel– the Prophets and the Writings.Fourth, the Samaritans believed the Judean Israeliteshad taken the wrong path in their religious practice of13

the ancient Israelite faith, which they branded asheretical, as the Jews did of the Samaritan’s faithexpression. The relationship between these twoancient groups can be compared to the sharpdisagreements between Shia and Sunni Muslims today.To outsiders, both groups are Muslim, but not to theShia and the Sunni. To them – one is true and theother is false; one is real and the other is an imposter.The Samaritan – Jewish conflict was in this sense verysimilar. In many ways, this conflict defined the innerIsraelite polemic of the first century.Fifth, as was mentioned before, the Samaritans are notto be confused with a syncretistic people group thatalso lived in Samaria (gentile residents of Samaria),who were most probably the people who approachedreturnees to Jerusalem to help them build theJerusalem Temple and were rejected by them (Ezra4:1-2). When Assyrians conquered the NorthernKingdom of Israel they repopulated the desolate landswith subjects from their own kingdom, loyal to thethrone. And these transplants from Mesopotamia livedalongside impoverished and devastated localpopulation, the remnant of those who were not ledaway into slavery. Due to the theology and rejection ofthe Davidic dynasty, by the Northern tribes theSamaritan Israelites, the remnant of devastatedkingdom of Israel, could not support Temple buildingin Jerusalem. In 2 Chronicles 30:1-31:6 we are toldthat not all the people from the northern kingdom ofIsrael were exiled by the Assyrians. Most of themremained even after the Assyrian conquest of the landin the 8th century BCE, preserving ancient Israelite14

traditions that would differ from later innovations ofthe Judean version of Israel’s faith.It is quite likely that some segments of the localpopulation mixed with the transplants from theAssyrian empire. So as a result, three kinds of peoplepopulated Samaria: the descendants of the NorthernTribes of Israel who kept the old ways, the foreignerstransplanted from Assyrian lands, and a newly-blendedcombination of the two. The confusing part is that allof them, regardless of their actual heritage or ideology,were called “Samaritans” because they lived inSamaria. So how can one know which Samaritan oneencounters in the story? This is not easy, but theanswer is - the context should give us a clue. This iswhy it is important to highlight the descendants of theNorthern Tribes of Israel as Samaritan Israelites.Sixth, the Samaritan Israelites used what is now called“Samaritan Hebrew” in a script that is the directdescendent of Paleo-Hebrew (ancient Hebrew), whilethe Jewish Israelites adopted a new form of square,stylized letters that were part of the Aramaic alphabet.Moreover, by the time of Jesus, the SamaritanIsraelites were also heavily Hellenized in Samariaproper and in the diaspora. Just as the Jewish Israeliteshad the Septuagint, the Samaritan Israelites had theirown translation of the Torah into Greek, calledSamaritikon.And lastly, the Samaritan Israelites believed that theirversion of the Torah was the original version and theJewish Torah was the edited version, which had been15

changed by Babylonian Jews. Conversely, the Judeanscharged that the Samaritan Torah represented anedition edited to reflect the views of the Samaritans.As you can see, this was not an easy relationship.But you may be familiar that the authors of the NewTestament express favorable attitudes towardsSamaritans. Who has not heard the parable of theGood Samaritan (Lk 10:25-37)? For centuries, Jesus’tale has inspired people to help their neighbors. Whatmade the good Samaritan so good to the first-centuryJewish audience? Why did Jesus even tell this story?There are parts of this story that people often missonly because they are unfamiliar with first-centuryJudaism. One reason may be that he saw what hethought was a dead body on the side of the road anddid not ignore it. What many readers of the story failto consider that the Samaritan and others who passedby did not know the person was alive. Once theSamaritan tried to help the stranger he realized that hewas alive.In Jewish culture to be unburied was perceived as acurse. Elijah prophesied that Jezebel would meet thisugly fate and, indeed, her dead body was torn apart bywild dogs (2 Kgs 9:34-35). In Babylonian exile, arighteous man named Tobit secretly buried the bodiesof other Jews whom the king had slaughtered (Tobit 1:16-20; c. 2nd century BCE). Mishnah preservesrabbinic thinking on the matter“A High Priest and a nazir [a person whotook a Nazarite vow] may not become16

impure for their relatives (Lev 21:11), butmay for an abandoned dead body.” (m.Nazir 7:1).Many people do not know this, but for ancient rabbis,even priestly purity was secondary to deeds ofkindness. Indeed, the Torah associates dead thingswith ritual impurity, and Moses did not give anycommands obligating one to bury an abandoned body.Those who passed the supposed corpse on the side ofthe road could have shown mercy, but instead, theyfollowed the letter of the law. The poor guy was dead.In Jesus’ day burying a body that no one else couldcare for was seen as a highly ethical deed, as a selflessact of kindness that cannot be repaid. Jesus asked,“Which proved to be a neighbor ” and he was told, “theone who showed mercy toward him” (Lk 10:36-37). Theanswer is obvious, the Samaritan, the person manywould not expect to go beyond the norm is the onewho showed extraordinary kindness to someone whowas not literally his neighbor.In Jesus’ teaching helios “compassion” “mercy” or“loving-kindness” chesed towards other peopletranscends all other commandments. A Samaritan wasan outsider, with no obligation to care for the corpseof a Jew, yet he showed compassion and thereby actedas a good neighbor. Let’s keep such positive Jewishperspectives on Samaritans in balance with the illfeelings of a long dispute about who is right. Its timeto look at the woman by the well.17

The Encounter at the WellIn describing the encounter, John makes severalinteresting observations that have major implicationsfor our understanding of verses 5-6: “So he came to atown in Samaria called Sychar, near the plot of ground Jacobhad given to his son Joseph. Jacob’s well was there, and Jesus,tired as he was from the journey, sat down by the well. It wasabout the sixth hour.” John mentions the Samaritan townnamed Sychar. It is not clear if Sychar was a villagevery near Shechem or if Shechem itself is in view. Thetext simply calls our attention to a location near theplot of ground Jacob gave to his son Joseph. Whetheror not it was the same place, it was certainly in thesame vicinity, at the foot of Mt. Gerizim.While this is interesting and it shows that John wasindeed a local, knowing the detailed geography of theplace, it is no less important, and perhaps even moresignificant, that the Gospel’s author calls the reader’sattention to the presence of a silent witness to thisencounter: the bones of Joseph.2 This is how the bookof Joshua relates to that event:2Josh. 24:32; Josephus, Ant. 2.8.2.18

“Now they buried the bones of Joseph, which thesons of Israel brought up from Egypt, at Shechem,in the piece of ground which Jacob had boughtfrom the sons of Hamor the father of Shechem forone hundred pieces of money; and they became theinheritance of Joseph’s sons” (Josh. 24:32).The reason for this reference to Joseph in verse 5 willonly become clear when we see that the Samaritanwoman suffered in a manner similar to Joseph. If thisreading of the story is correct, just as Joseph enduredunexplained suffering for the purpose of bringingsalvation to Israel; likewise the Samaritan womanendured suffering which led to the salvation of theSamaritan Israelites in that locale (4:39-41).“ 6Jacob’s well was there, and Jesus, tired as hewas from the journey, sat down by the well. Itwas about the sixth hour”.19

It has traditionally been assumed that the Samaritanwoman was a woman of ill repute. The reference tothe sixth hour (about midday) has been interpreted tomean that she was avoiding the water drawing crowdof other women in the town. The biblical sixth hour3was supposedly the worst possible time of the day toleave one’s dwelling and venture out into thescorching heat. “If anyone were to come to drawwater at this hour, we could appropriately concludethat they were trying to avoid people”, the argumentgoes. We are, however, suggesting another possibility.The popular theory views her as a particularly sinfulwoman who had fallen into sexual sin and thereforewas called to account by Jesus about the multiplicity ofhusbands in her life. Why did she have so manyhusbands? Jesus told her, as the popular theory has it,that He knew that she had five previous husbands andthat she was living with her current “boyfriend”outside the bonds of marriage, and therefore she wasin no condition to play spiritual games with Him! Inthis view, the reason she avoided the crowd wasprecisely because of her reputation for short-livedmarital commitments. But there are problems with thistheory.First, midday is not the worst time to be out in thesun. If it was 3 pm (ninth hour) the traditional theorywould make better sense. Moreover, it is not at all3Hence the shock of the darkness at the sixth hour when Jesus died (Matt.27:45; Mk. 15:33; Lk. 23:44).20

clear that this took place during the summer months,which could make the weather in Samaria altogetherirrelevant. Secondly, is it possible that we are makingtoo much of her going to draw water at “an unusualtime?” Don’t we all sometimes do regular thingsduring unusual hours and could it be possible that thisis such a case? This does not necessarily mean we arehiding something from someone. For example, weread that Rachel came to the well with her sheepprobably also at about the same time (Gen. 29:6-9).There are also other problems with this reading of thetext. When we try to understand this story with thetraditional mindset, we can’t help but wonder how itwas possible, in this conservative Samaritan Israelitesociety, that a woman with such a bad track record ofsupporting community values could have caused theentire village to drop everything and go with her to seeJesus (4:30). The standard logic is as follows: She hadled such a godless life that when others heard of herexcitement and newfound spiritual interest, theyresponded in awe and went to see Jesus forthemselves. This rendering, while possible, seemsunlikely to the author of this book, and seems to readmuch later theological (evangelical) approaches intothis ancient story, which had its own historical setting.I am persuaded that reading the story in a new way ismore logical and creates less interpretive problemsthan the commonly held view.Let us take a closer look at John 4:7-9:21

“When a Samaritan woman came to drawwater, Jesus said to her, ‘Will you give me adrink?’ (His disciples had gone into the townto buy food). The Samaritan woman said tohim, ‘You are a Jew and I am a Samaritanwoman. How can you ask me for a drink?’(For “the Jews” do not associate withSamaritans)”.In spite of the fact that, to the modern eye, thedifferences were insignificant and unimportant, Jesusand the nameless Samaritan woman were from twodifferent and historically adversarial people, each ofwhom considered the other to have deviateddrastically from the ancient faith of Israel. Asmentioned above, a modern parallel to the JudeoSamaritan conflict would be the sharp animositybetween Shia and Sunni Muslims. For most of ustoday Muslims are Muslims, but within Islam, this isnot an agreed-upon proposition. Both parties considereach other as the greatest enemy of true Islam. So, too,for the people in the ancient world. These two warringpeople groups were Israelites and were both a part ofthe same faith. However, they were bitter enemies.This was not because they were so different, butprecisely because they were very much alike.Both Israelite groups considered the other to beimposters. While we don’t have Samaritan sources totell us their official position, we do know that a latersource, the Babylonian Talmud, referring to the viewsand practices of the distant past, states: “Daughters ofthe Samaritans are menstruants from the cradle”22

(Babylonian Talmud, Niddah 31b) and therefore anyitem that they handled would be unclean to theJudean4.The Samaritanwomanprobablyrecognized thatJesus wasJudean by hisdistinctiveJewishtraditionalclothing andhis accent (It ishighly likelythat theconversationtook place inthe tonguefamiliar to them both). Jesus would have mostcertainly worn ritual fringes (tzitzit) in obedience tothe Torah/Law of Moses (Num. 15: 38 and Deut.22:12), but since Samaritan Israelite men observedTorah as well, this would not have been adistinguishing factor. The difference between thesetwo groups was not whether the Torah of Moses mustbe obeyed, but how it should be obeyed.4The Mishnah also explores the ritual and ethnic identity of Samaritans(mDem. 3:4; 5:9; 6:1; 7:4; mShev. 8:10; mTer. 3:9; mSheqal. 1:5; mKetub. 3:1).23

Gender relationships have changed throughout the agesof history, affected by culture and social boundaries. Iwould suggest that we know little of what ancientIsraelites felt about the proximity of genders and touchbecause we are profoundly affected by our own culturalideas without evening realizing it. One text that remainsan enigma to most Christ-followers is the postresurrection story in the twentieth chapter of John’sgospel where Jesus cautions Mary to avoid touchinghim, but a week later invites Thomas to do just that.Mary, seeing her beloved and presumed-dead rabbi nowalive, attempted to hug the resurrected Jesus (vs. 16).He emphatically told her that she could not touch himbecause He had not yet ascended to his Father (vs. 17).Shortly after (when all the disciples were gathered toregroup) Christ appeared to them resurrected! Thomaswas absent from this gathering (vss. 19-21). Later, whenthe disciples reported to Thomas that they had seenJesus alive, he understandably responded withskepticism (vs. 24). Eight days later, Jesus unexpectedlyappeared again to the gathered disciples and challengedThomas to touch him by placing his hands into theholes that remained in his body (vs. 26-27). Theobvious question is this: why did Jesus deny Mary, butlater encourage Thomas to touch Him?In order to understand Jesus’ very different instructionsto Mary and Thomas, we need to understand the purityrequirement for the Jewish High Priest on the Day ofAtonement. The High Priest was forbidden to comeinto contact with anything that was ceremonially24

unclean in order to avoid being disqualified to enterGod’s presence the following day. So much dependedon this ritual purity! After His resurrection, Jesus (asour ultimate High Priest) would shortly be ministeringin the heavenly tabernacle (Heb. 9:11). It is significantthat Jesus appeared to the disciples and told Thomas totouch him after eight days because it takes seven daysto ordain a priest (Ex. 29:35).The most likely reason for Jesus’ instructions to Marynot to touch him had to do with the fact that He wasdetermined to enter the heavenly tabernacle in a readyto-serve, consecrated state. Defilement would not be asin, but it would have disqualified Him (for a period oftime) from entering God’s presence. Mary may havehad a number of reasons for defilement (possiblemenstrual circle, stepping into the tomb, etc), Jesus’priestly mission was too important to allow for anypossibility of failure. By the time Jesus met Thomas,His priestly work is done. He had returned fromcompleting His duties and possible defilement was nolonger an issue. So it is not that a woman could notcome close and touch Jesus because something waswrong with them touching or being close. At thatmoment her touch would interrupt somethingsupremely important. The reason is veiled from mostpeople because we fail to understand this sort of life. Itis not a part of our modern world and thinking.Jesus’ role as a prophet was carried out during Hisearthly life. His role as king was yet to be realized at thetime of the ascension. He first needed to be ordained a25

priest and carry out His duties in the heavenlytabernacle! Nothing could be permitted to stand in theway of his mission.The same is with the Samaritan woman. You want todrink from my water vessel? You want to touchsomething of mine, she says to Jesus? That is herpuzzled response. But does that response have more todo with her being a woman or a Samaritan? We oftentransfer our own ideas about gender proximity intoancient stories like this one. But we do not fullyunderstand what reasons stand behind distance andproximity between people depicted in such ancientsettings.Relationships between people groups can be verycontroversial. Outsiders rarely understand what is thereason they dislike each other and why they can’t getalong. If outsiders ever hear some of the reasons theyappear trivial. The apprehension of inter-ethnic contactis rarely appreciated by modern people living inethnically diverse modern societies. By that was not theworld of the gospels.Two Gospels record a meeting between Judean Jesusand a Greek woman. (Mk.7:24-29; Matt.15:21-28). Jesusgoes to Tyre and Sidon (allotment territory of the tribeof Asher that was never fully taken over by Israelite).There he meets a desperate mother willing to doanything for her suffering child: “Have mercy on me, Lord,Son of David! My daughter is severely tormented by a demon”(Mat. 15:21-22). As we continue reading we see that26

Jesus first gave her the silent treatment. Then, when hisJewish disciples demanded he answer her, heresponded: “I was sent only to the lost sheep of the house ofIsrael”. However, the woman was relentless. “She came,knelt before him, and said, “Lord, help me!” He answered her:“It isn’t right to take the children’s bread and throw it to thedogs” (Mat. 15:23-26).The most offensive statement, of course, has to do withJesus’ comparison of Greek Gentiles to dogs. The keyto understanding this text is found in the realizationthat only in the modern Western world dogs arethought to be part of the family. Dogs (often) liveinside and not outside of the family home, but it wasnot so in ancient times in the East. In other words, thecomparison to dogs was not meant to dehumanize theGreek woman but to emphasize that Jesus’ primarymission was to Israel – to those inside of God’s family,not outside of it.Understood this way, we see that there was nothingdehumanizing in Jesus’ response. It is no different fromwhat Apostle Paul would later write: “ the power of Godfor salvation to everyone who believes, first to the Jew, and also tothe Greek”. In spite of some misunderstood statementsabout his seeming disregard for the physicalfamily, Jesus here says – family first! But what madeJesus act differently towards her now? Clearly it was herresponse: “Yes, Lord”, she said, “yet even the dogs eat thecrumbs that fall from their masters’ table”. Then Jesus replied toher, “Woman, your faith is great. Let it be done for you as youwant”. (Matthew 15:27-28)27

This Sidonian woman displayed the true faith of Israelexemplified in the Torah by both Abraham and Moses.Just like them, she was willing to argue with God,believing with unwavering faith that He is just, goodand merciful. This is not exactly the position ofSamaritans. As far as they were concerned the Judeanswere wrong and Samaritans followed the true way.Jesus continues:“‘If you knew the gift of God and who it isthat asks you for a drink, you would haveasked him and he would have given you livingwater.’ 11‘Sir,’ the woman said, ‘you havenothing to draw with and the well is deep.Where can you get this living water? 12 Areyou greater than our father Jacob, who gave usthe well and drank from it himself, as did alsohis sons and his flocks and herds?’ 13 Jesusanswered, ‘Everyone who drinks this waterwill be thirsty again, 14but whoever drinks thewater I give him will never thirst. Indeed, thewater I give him will become in him a springof water welling up to eternal life’. 15Thewoman said to him, ‘Sir, give me this water sothat I won’t get thirsty and have to keepcoming here to draw water’. 16 He told her,‘Go, call your husband and come back’. 17‘Ihave no husband,’ she replied. Jesus said toher, ‘You are right when you say you have nohusband. 18 The fact is, you have had fivehusbands, and the man you now have is notyour husband. What you have just said is1028

quite true.’ 19‘Sir,’ the woman said, ‘I can seethat you are a prophet. 20Our fathersworshiped on this mountain, but you “Jews”claim that the place where we must worship isin Jerusalem’”.This passage has often been interpreted as follows:“Jesus initiates a spiritual conversation (vs. 10). Thewoman begins to ridicule Jesus’ statement by pointingout his inability to provide what he seems to offer(verses 11-12). After a brief confrontation in whichJesus points out the lack of an eternal solution to thewoman’s spiritual problem (verses 13-14), the womancontinues with a sarcastic attitude (vs. 15) Finally,Jesus has had enough and he then forcefully exposesthe sin in the woman’s life – a pattern of brokenfamily relationships. (verses 16-18) Now, cut to theheart by Jesus’ all-knowing x-ray vision, the womanacknowledges her sin in a moment of truth (vs. 19) bycalling Jesus a prophet. But then, as every unbelieverusually does, she tries to avoid the real issues of hersin and her spiritual need by raising doctrinal issues(vs. 20), in order to avoid dealing with the real issuesin

God’s forgiveness. When it became clear to Jesus that the crowds were growing large, and especially when he heard that this alarmed the Pharisees, he decided it was time to go to Galilee through Samaria (verses 1-3). And this is where the story explained it this book oc