Transcription

he Power of NarratThe connectionmaynotThis is certainly not the correctseem obvious, but written impression to give. The Hittitessources are an integralbuilt no institution that approachedpart of the archaeological the functioning of a library.We canrecord.In addition to being thenot even be sure that the structurescornerstone of any hermeneuticalin which tablets have been foundwere actually intended to be tabletprocess, they are an important toolin helping us understandthe mutehouses, or archives, in the physicalsense of the word. Thus, in this ararchaeologicalremains. Writtensources are critical in the study ofticle, the word archive is used toHittite Anatolia not only becausedenote the collections of tablets thatthey providestraightforwardhistori- have been found throughout thecal accounts of the Hittites but also Hittite capital. Relatively few tabletsbecause they illustrate the literaryhave been found in the provincesvalues and abstractthought pro(compareOzguic1978: 57-58).The tablets unearthedat Hattusacesses that pervadedevery aspect ofwere scattered in buildings throughHittite life. The study of Hittiteliterature illustrates that archaeout the site. In the LowerCity, tablets were found in severalrooms ofology and philology are indeedcomplementary disciplines and that Temple 1, the great temple of thetheir relationship must be carefully Weather-God(Otten 1955: 72; Bittelcultivated if we are to unravelthe1970: 13-14; Naumann 1971:430;puzzles of the past. In the following Akurgal 1978:302). On the acropolis,site of the greatfortressof Biyiikkale,pages I will discuss the underlyingelements of the Hittite literary tradi- tablets were found in three struction and present severalpassagestures-Buildings A, E, and K (Bittelfrom various texts to show both the1970: 84-85, 163).Many tablets werealso found in the so-called House ondevelopment of that tradition andthe power of its prose.the Slope (Schirmer1969:20), perhaps the scribal school (MacqueenThe Hittite Archives1986: 116,note 71).More tablets areThe obvious place to begin any disbeing unearthed in the Upper Citycussion of Hittite literature is the(Otten 1984: 50, 1987:21; Nevearchives at the Hittite capital of Hat- 1985: 334, 344, 1987a: 405, 1987b:tusa near the modern-daydistrict311),among them a sensational tabtown of Bogazkoy/Bogazkale(seelet made of bronze that was foundunderneath the paving stones alongAkurgal 1978:300-01). Althoughlittle has been written about the ar- side the inner city walls near Yerkapichives (Laroche1949;Otten 1955,(Neve 1987a:405; Otten 1988, 1989).We can say very little about1984, 1986),it is from these writtensources that we get our initial imthe physical structures in whichpressions of the role literatureplayed the Hittites kept and stored theirin the Hittite state.tablets. At Hattusa tablets wereWe must be cautious, however, found collected in temples, houses,when speaking of the Hittite armagazines, and perhapsspecial tabchives. The word archive connoteslet houses. Others were discovereda building or structure and impliesin widely scattered areas and dumps.the notion of a libraryor the like.There does not seem to have been a130Biblical Archaeologist, June/September 19894d?PlWl-."411.710,.A:*evb1 .O*. .mparticularsystemof distribution.(An overview of find spots accordingto CTH numbers can be found inCornil 1987.)Wehave determined how thetablets were organizedfrom thestructures in which they werehoused as well as from the so-calledshelf lists (Laroche1971: 154).It ispresumed that these shelf lists wereplaced as indices in front of the tablets for quick reference.Some of the.,

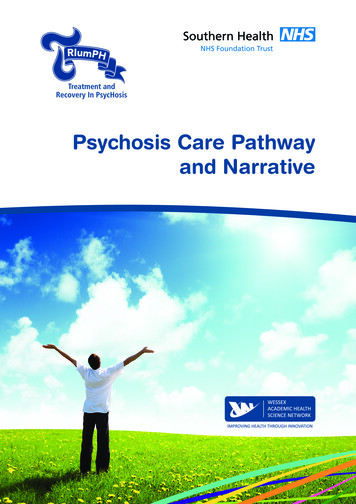

*inHittiteLiteraturebyAhmet-UnalTabletshave been found scattered throughoutthe Hittite capital of Hattusa, including thegreat temple of the Weather-God,shownhere, located in the LowerCity. The entirecomplex, including the central courtyardandsurroundingstorerooms,measures about 525feet at its longest point. Visible in the rearofthe photo, attached to the central courtyard,is an annex with ritual chamber (adyton).Photo by Ronald L. Gorny.addition to the land grants,HurroHittite bilingual literary texts,rituals, letters, and divination textshave been found as well as the previously mentioned bronze tabletthat details the treaty between Hattusili IIIand his nephew, Kurunta,the vassal king of Tarhuntassa(Otten in Neve 1987a:405; Otten1988, 1989).C. .A' ---istructures, especially Buildings Aand K in Biiyiikkale, had rooms withparallel rows of stone pillars thatmight have supportedwooden racksor shelves for the tablets ratherthana second story (Neve 1982: 106, 108,and plans 41, 45). At one time thetablets may have resided in a fewspecially established tablet houses,but it is possible that some tabletswere moved to secondary locationsduring the rebuilding and reorgani-zation of the city in the final phaseof the empire (Laroche1975: 57;Bittel 1970: 85). This may be illustrated by the discovery of Old andMiddle Hittite land grants dating tothe sixteenth and fifteenth centuriesB.C.E. in the newly excavatedtemplesin the Upper City (Otten 1987),which date to the thirteenthcentury B.C.E.Other types of tablets have alsobeen found in the Upper City. InHittite Scribes and the Pursuitof WritingIt appearsthat writing was broughtto Anatolia by the Old Assyrianmerchants who established tradingcenters in important cities acrossthe central plateau during the earlypart of the second millennium B.C.E.The Assyrians brought their ownsystem of writing, called Old Assyrian script, the use of which isthought to have died out with thedemise of the karum system around1750 B.C.E. The Old Babylonianscript, on which Hittite was based,is generally thought to have beenfirst used somewhat later by OldBabylonianscribes who are said tohave been brought t9 Hatti duringthe campaigns of the first Hittitekings into northern Syria (Beckman1983: 100, note 17).It has always been thought thatthe use of these two scripts wasmutually exclusive because theypertained to different eras that wereseveralhundredyears apart. Such aBiblical Archaeologist, June/September1989131

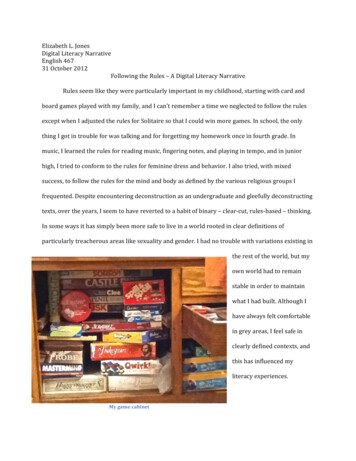

Most of the best-preservedclay tablets in the Hittite archives were found in this structure,Building A in Byuiikkale, the fortresslocated southeast of the great temple at Hattusa. About105 feet long, Building A consisted of four storeroomsand a long lateral corridor.Picturedinthe storeroomsare the remaining rectangularlimestone bases that once supportedparallelrows of pillars, which might have supportedwooden racks or shelves for the tablets ratherthan a second story of the building. Stone bases were not found in the long, outer room to theeast of the storerooms.Courtesyof PeterNeve and the GermanArchaeologicalInstitute.1IIIscenario would leave a literarygapof between one and two centuriesin central Anatolia. In the view ofHans Guterbock (1983a:24-25), it ispossible that the princes of the earlycity-statesemployedAssyrian-trainedscribes to document their dealingswith the Assyrian merchants andBabylonian-or Syrian-trainedscribesfor documents written in Hittite.Examples to support this idea, however,have not turned up in anyexcavation.132The Anitta Text (CTH 1),oneof the oldest Hittite texts, may be thetranslation of a text originally written in Old Assyrian, then the onlyliterary language in central Anatolia.Some scholars suggest, however,thatthe piece displays none of the qualities generally found in a translation(Neu 1974: 132;see overview inUnal 1983b)and that it may havebeen originally written in Hittite a:24-25). As theBiblical Archaeologist, June/September1989bullae from Acemhoyuk suggest(N. Ozgufc1986:48), non-Assyrianscribes could have been plying theirtrade in the central Anatolian Highlands long before the alleged importation of the Old Babylonianscriptduring the reign of Hattusili I. Thiswould suggest that the origins ofHittite literature could go somewhatfartherback than originally thought,possibly pulling the date of Anitta'sreign closer to the supposedorigins ofHittite history. This theory remainsvague, however,and still offers noclue as to Anitta's ethnic origin.Contacts between central Anatolia and northern Syria are knownto have alreadytaken place in thelast half of the third millenniumB.C.E.(T. Ozgui 1986:31). The city ofKaneswas probablya principalpartnerin this trade,so it is not unreasonableto think that the cradleof Anatolian literary developmentcould be found there. The fact thatthe languageof the Hittites is callednesumnili-"in the languageofNesa"- lends credibility to this suggestion. Could it be that the Hittiteswere alreadydevelopingthe rudiments of a written languageduringthe period of the Assyrian merchants? There is no evidence to substantiate this suggestion at present,but excavations in the non-Assyrianparts of Kultepe may eventually bearit out.The heyday of the Babylonianscribes in Anatolia seems not to haveoccurreduntil after the period of theAssyrian trade settlements, however.There is well-documented evidencefor such a presence in the late fourteenth and the thirteenth centuriesB.C.E.,but the traditionprobablydateseven earlier since a Babylonianscribal school had apparentlybeen established at Hattusa by the late fif-

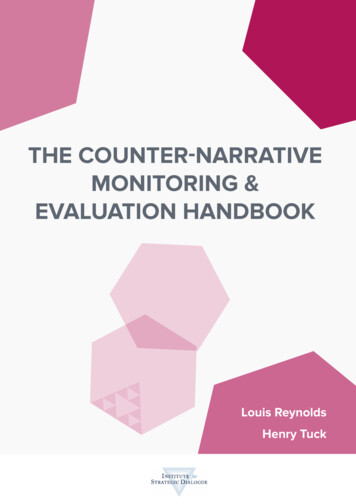

The heyday of the Babylonianscribes seems to have occurredafter the Assyrian settlements.Tabletsmay have once resided in specially established tablet houses, but it is possible thatsome might have been moved to secondary locations duringthe rebuilding and reorganizationof Uattusa in the final phase of the empire.The discoveryof land grantsdating to the pre-Empireperiod, like the two picturedhere, may illustrate this possibility. The cuneiform seal in thecenter of the clay tablet to the left identifies it as belonging to Zidanta, an Old Kingdomruler,whereas the land grant to the right is identified by its center cuneiform seal as belonging toArnuwanda I, a Middle Kingdomruler.Both tablets were discoveredat the site of ancientHattusa. Photos courtesy of PeterNeve and the GermanArchaeologicalInstitute.teenth or early fourteenth century(Beckman 1983: 106).It is importantto add that the Hurrian scribal tradition was having an immense impactat the time (Mascheroni 1984),andmany of the Mesopotamian influences noted in later Hattusa mayhave originally been transmittedthrough this medium.One type of Hittite scribe wascalled the scribe of the woodentablets, which may be a referencetoscribes who wrote on folding woodentablets constructed with a recessedareato hold a wax substance onwhich daily notices and receiptswere written. No traces of this highly perishable material have beenfound preservedin Anatolia, but oneexample was recently excavatedabout 150 feet underwaterat the siteof an ancient shipwreck off the coastof Turkeyat Ulu Burunnear Kas.Thetablet has been called the world'soldest known "book"(Bass1987:730).Another writing system thatwas practicedby the Hittites is theso-calledLuwianhieroglyphs.Scribeswho used wooden tablets might haveused this style of writing instead ofcuneiformfor their day-to-dayrecords.Although Luwian hieroglyphs seemto have been popular in the middleof the second millennium B.C.E.,some efforts have been made to pushthe origins of this writing systemback as far as the third millenniumor the first half of the second millennium, but without convincing proof(overviewby Alp 1968:281).The Earliest LiterarySourcesHittite literature appearedon thescene in an alreadywell-establishedstyle soon after the foundation ofthe Old Kingdom and the adoptionof the Old Babylonianwriting sys-Biblical Archaeologist, June/September 1989133

tern. It seems clear that some sortof developmental stage must havetranspiredprior to its full-blownappearanceas the literary mediumin central Anatolia. Whether thismedium was the result of an earlierdevelopment in the so-called DarkAge, of Syro-Babylonianinvolvementduring the reign of Hattusili I, oreven of Hurrianscribes remainsdebatable,but future researchwillcertainly reveal an enormous Hurrian impact on Hittite literacy.Agreat deal of new evidence will eventually come from Hattusa as well assoutheastern Anatolian and northSyrian sites, and these texts mayenlighten us about the origins of theHittite script. The fact remains,however,that we now see no obviouspreliminary or experimental stage ofdevelopment. This is the case inmany Hittite genres, but especiallyin the literature that displays a complex narrationof events and procedures, examples of which are foundin the earliest written sources.The Political Testament of Hattusili I (CTH 6), for instance, gives averbatim recordof a speech given bythe king to an assembled court forthe purpose of dismissing his sonfrom succession to the throne. Especially poignant are the followingpassages:"I,the king, called him my son,embracedhim, exalted him, andcaredfor him continually. Buthe showed himself a youth notfit to be seen: He shed no tears,he showed no pity, he was coldand heartless."The force of the narrativeleads oneto anticipate the conclusion:"Enough!He is my son no more!"(Gurney 1981).Throughout the text there is notrace of scribal alteration;it seems134This twice-impressedenvelope of an Old Assyrian tablet was found in Level lb at Ktiltepe,site of ancient Kanes. In the scene, worshippersare guided by a God-King.Above the wideguilloche are two sphinxes with an ankh sign between them; below them is a bull scratchingthe groundand an eagle seated upright.Most tablets from Kiltepe lb have this type ofimpression. Photo courtesy of TahsinOzgiic.to have been recordeddirectly fromthe king's mouth.The so-called Palace Chronicle(CTH 8), a series of anecdotal admonitions, illustrates a distinctgenre that seems to have emergedduring the Old Hittite kingdom.This collection, which has been preserved on many tablets dating to different periods of Hittite history, isnot simply part of an oral tradition.As reflections of real events, thesestories played a propagandisticrolein the Hittite subjugationof the Anatolian population, revealinga way oflife that was vital and dynamic onthe one hand and harsh and brutalBiblical Archaeologist, June/September 1989on the other. The persons mentionedin these stories seem to be partlyhistorical, partly fictional. The collection can be considered a literaryachievement because of its uniquestyle of narration.The languageiscryptic, but the author'seffort iskeenly felt as he tries to impress hismessage with words calculated toinstill fear in wrongdoers.Takenfrom different aspects of daily life,the anecdotes seem to encourageloyalty and good conduct by illustrating that evil will be punishedand that good will be rewarded:(Oncethere was) a high functionary named Pappa.He was found

(ancient Kanes)is this Old Assyrian tablet with a seal impression of a double-headedeagle within aLeft:Also found at Level lb at Kiiultepeguilloche borderwith a star on each side between the tail and wings. Photo courtesy of TahsinOzgii,. Right: Some Hittite scribes wrote onfolding wooden tablets constructed with a recessed area to hold a wax substance on which daily notices and receipts were written. No tracesof this highly perishable material have been found in Anatolia, but this wooden tablet, shown vertically,was recently found about 150 feetunderwaterin an ancient shipwreck excavated off the coast of Turkeyat Ulu Burun,near Kay.The tablet, or diptych, has been called theworld'soldest known "book."Photo courtesy of GeorgeF Bass and the Institute of Nautical Archaeology,TexasA & M University.head (KBo3.34 I 5-g).to be fraudulently distributingarmy-breadand marnuwan-drink Other Old Hittite authors also used(amongthe people) in the city of the power of narrativeto make theirpoints. In contrast to later literature[Tameni]nka.(The authorities)[squashed]the breadand smeared with its emphasis on divine inspiration and empowerment, this powerthe upperpart of his body (withwas often rooted in the omnipotenceit). (Further)they poured outand wisdom of the king. Thus wesalt into [marnuwan-]cupandshould not be surprisedto find exmade him drink it. They brokethe cup on his head. (Because)amples where the king is presentedas making wise pronouncementshe (also)was distributing inthat imply great royalpower.In theHattusa (illegally) walhi-drinkto the soldiers, they took a sagga- Benediction for Labarna,for example,the king commands:vessel and broke it (too)on his"Letthe whole country be inclined towardHattusa behindhis back. The king himself isvigorous. He is (also)able tokeep the country vigorous. Theking's house is (full)of rejoicingand grandchildren.It is set on(solid)ground"(KUB36.110rev.9'-16').Similarly there is a royal admonition to:"givehim (that is, a sick person)breadand water. If somebody isstruck by heat, let him be takenBiblical Archaeologist, June/September1989135

The longest hieroglyphicmonument dating to the Hittite Empireperiod is this weathered,11-lineinscriptionlocated on a sloping hill at Nisantepe in the UpperCity at Hattusa.About 28 feet long, the inscription apparentlydates to the reign of SuppiluliumaI. Photo byRonald L. Gorny.to a cool place; if the cold chillssomebody, let him be taken to awarm place. Let the king's subjects not be oppressed!"(Archi1979:37).These passages have been comparedwith a story detailed in a HurroHittite bilingual from Hattusa inwhich the Storm-GodTesubhasgotten into debt (KBo32.15 i-ii; Neu1988a: 16, 1988b, 1988c, 1988d).While Tesubtries to extricate himselffrom the situation, other gods assisthim as a token of solidarity, supplying him with silver, gold, food, garments, and refined oil, all of whichhe needs. Such acts symbolize liber-136ation or releasing (paratarnumar),which is the main theme of Old Hittite stories. In light of Hittite interaction with nearbyHurrianprincipalities, we should ask to what extentthese genres are to be consideredstrictly Hittite since there is strongevidence that many typically Hittiteideas were actually borrowedfromthe Hurriansand the Babylonians.One of our first examples ofHattusili I'sinvolvement in militaryaffairsis the Akkadian text describing the Siege of Ursu, an importantHurriancity in southeasternAnatolia(Beckman,forthcoming).The textdescribes the toils and frustrationsBiblical Archaeologist, June/September1989felt by the king duringthis bittersiege in which Hittite forces wereevidently inferior to the Hurriansinboth manpowerand equipment. Inaddition, the Hittite military commanders are described (in a surprisingly frank manner) as weak, slack,and ineffective. Thus it is left to thetireless and courageousefforts of theHittite king to overcomethe Hurrianforces who are proppingup the cityof Ursu. The king's frustrationis evident in his animated response tofinding out that the battering ramhas been broken:The king waxed wrath and hisface was grim (as he yelled),

Old Kingdom literature tried toinvolve the reader so that theconclusion was seen as inevitable."Theyconstantly bring me eviltidings; may the Weather-Godcarryyou away in flood! Be notidle! Make a battering ram inthe Hurrianmanner and let itbe brought into place. Make amountain (thatis, siege machine)and let it (also)be set in its place.in its place. Hew a great battering ram from the mountains ofHassu and let it be brought intoplace. Begin to heap up earth.When you have finished let everyone take post"(KBo1.10 obv.!13'-17' translatedby Gurney1981: 180-81).It is almost as if the king were saying, "Do I have to tell you how to doeverything?"These descriptions are as mucha literary device as a historical narration of the facts. They set the stagefor a statement of the king's wiseand courageous decisions, the purpose of which is to emphasize hisrole and lead the readerto the obvious conclusion that without theking all would be lost. Unfortunately, the end of the story is missing(but compare the Annals of Hattusili I in KBo 10.1 i 15 and following).The Old Hittite culmination ofthis literary pattern is found in theTelipinu Edict (CTH 19).The powerful narrationof the tragic eventsleading up to this decree presentsthe readerwith what amounts to anapologetic discourse. In contrast tothe passionate pronouncement ofHattusili I, this decree is formulatedin a very unemotional way and withan objectivity peculiar to legal texts.It is, however,a very idealized account of the remote past presentedin a schematized form that leavesone with a strong impression of theforce of law. Like the Political Testament of Hattusili I, the TelipinuEdict has a sense of growing anticipation and fulfilled expectation,which inevitably arise with the finalstipulations of the decree. Telipinuthus succeeds in presenting his reforms, not as mere stipulations butas a well-structuredliterary composition (Sturtevantand Bechtel 1935:175;Hardy 1941: 190;Liverani 1977:105;Hoffmann 1984: 13).to Mount Arinnanda.Now thisMount Arinnandais very steepand extends into the sea (that is,it is on a peninsula). It is alsovery high, difficult of access,rocky, and impossible for chariots to drive up. Since it wasimpossible to drive with chariots, I, my majesty,went guidingmy army in front on foot andclamberedup Mount ArinnandaThe Development of an Emphasison foot"(Goetze 1933: 54).on the DivineThe facts are clearly organized,butThe literature of the Old Hittitethe presentation is farfrom n is constructed tooutline in which the Hittitesmake the readersympathize withcouched much of their later literathe king and his difficulties at theture. Basic to this style is an attempt same time commending his courageto involve the readerin the eventsand wisdom in making tactical andbeing described so that the constrategic decisions. It is also notableclusion is seen as inevitable. Thefor the gratitude that the king acoutcome is determined by the wisecords his patron deity whom he beactions of the king on one hand andlieves supports him throughout histhe leading heroes on the other.lifetime. In fact, this deity may haveOther genres borrowedheavilybeen thought to be the sole readeroffrom this style, for example, the anthe text. That is, the king presentsnalistic tradition. Although thean account of his reign to his divinemost fully developedexample of this overlordfor whom he governstheHatti lands as a proxy.This may bevery Hittite genre dates to the reignof Mursili II, forerunnerscan bethe precursorof depicting kingshipfound in texts dating to both the Old in terms related not so much toand the EarlyNew Kingdoms,such as wisdom and courageas to divinethe annals of Hattusili I, Tudhaliyaprovidence and empowerment. ItIII,and ArnuwandaI. These texts are foreshadowsthe "orientalizing"not merely recordsof events; theyof Hittite kingship, which came toare realistic narrativesof campaignfruition under the last kings ofthe empire.strategy that attempt to involve thereaderin the development of variousThe best example of this newideas to their expected conclusionstrend can be seen in the Apology(Cancik 1976).Precedingevents and of Hattusili III(CTH 81), a highlysimultaneous actions and circumsophisticated and unique composistances are describedperfectly,andtion whose purpose was to justifythe underlying reasons for the decihis seizing the throne. Hattusili tellssions are aptly given. In the Annalsabout his childhood, describing howof Mursili II, for example, we read:he was dedicated to the goddess Istarand how he, always an innocent"(Becausethe whole enemypopulation fled to Mount Arin- babe, was surroundedby jealousnanda)I, my majesty,went (also) enemies. Except for the deity, almostBiblical Archaeologist, June/September 1989137

Hurro-Hittite bilinguals are rareexamples of what in Mesopotamiawas called wisdom literature.everybodyis presented as envious ofthis child prodigy.The story goes onto tell how Istarenabled Hattusili toprevailagainst the continuous evildeeds and plots concocted by theseenemies. This document, which hasfew parallels in pre-Classicalantiquity, suggests a highly developedpolitical consciousness that relieson reasonedargumentation to makea point (Goetze 1925; SturtevantandBechtel 1935:64; Wolf 1967;Onal1974:29; Otten 1981).As with itspredecessors,this trend is dependenton the reader'sinvolvement: Its success relies on the powerof the narrative to lead the readersubconsciously to a desired conclusion, inthis case, that Hattusili had done nowrong but sat on the throne only asa result of his natural right of succession and divine selection.Narrationin LegallTxtsNarrationwas just as powerfulin thelegal sphere, especially in puttingforwardspecific cases. Hittite legalprocess used oratoryand complexreasoning in the pleading of cases.Among the official documents wehave found are depositions, that is,testimonies from the proceedingsoflegal inquests. There are,forexample,speeches made in self-defensebymen accused of having stolen or lostitems for which they had been givenresponsibility.These testimonies,which are preservedin the recordsofHittite court clerks, deserve specialtreatment here because they are theliterary forerunnersof pre-Socraticapologetics that use oratoryas ameans of self-defense.The best example of these testimonies is the case of Istar-ziti,whowas apparentlyindicted for a scandalous affairof unknown nature. Inhis defense Istar-zitiuses metaphors138such as "Iam cast down like a reed onthe darkearth"and "asa living personI am dead in the eyes of my siblings."A few more of his well-turnedphraseshelp illustrate this style:"HaveI not alwaysbeen a (true)The Role of the HurriansThe intermediaryrole of the Hurriansis one of the most important occurrences in Hittite history because itbrought about the incorporationofHurriancustoms and beliefs into theservant of that deity? . . . Onceindigenous Hittite culture.Hurriansfirst appearin the hiswhen I was taken ill, I prayedtothe gods, saying:'Do not youtorical texts as enemies of the Hittites. Convincing evidence is lacksee, o gods, who has ruined melike this (as I am right now)?'ing, but direct influence may alreadyhave begun in the Old Kingdom.Insteadyou have weighed onVisible influences are more readilyme! (Isit because) you do notobservedfrom the EarlyEmpireperiwant to harm (literally defeat)od under TudhaliyaIIIand Arnuwanthe king, his majesty?If youda I. By the time of Hattusili IIIandalways appreciatethe absolutetruth, why is it that matters are his Hurrianwife Puduhepa,thestill concealed? . . . When someHurriancultural invasion was wellthing evil happenedto the royal under way.From the EarlyEmpireheir in the city of Kummanna,on the Hurrianinfluence began to beAli-Sarrummarevealedto mefelt so strongly that some scholarsthat they intended to kill mebelieve the dynasty to be of Hurrianorigin. Indeed much evidence points(becausethey thought I wasto this conclusion. A case in point isguilty in that matter). (On mythe largenumber of Hurriantexts orway to Mount Sahhupidda)thequeen intended to have someone their translations found at Hattusa.lie in ambush behind the roadThese include the Kingship in Heaven story and the Song of Ullikummi.and kill me! . (From my eyes)Of special interest are the newly disthe tears flow [like water in untains].give to the priest of the Sun-God from the Upper City, which will cerand he shall pour them out setainly change our views of Hittiteintellectual life during the last twocretly for the Sun-God. Onecenturies before the downfall of theday in the city of Sulama I wasempire. It would be appropriate,honoring the god Tarupsani.therefore,to take a closer look at the(A man by the name of) Muticontents of these newly discoveredwalked in and startedto gossipabout my person. I seized himtexts, so faras details areyet available.The Hurro-Hittitebilingualsby the collar (and)broughthimto [the sacredplace]. I made him (Otten 1986;Neu 1988a, 1988b,take an oath and warnedhim (at 1988c)are rareexamples of what inthe same time), saying:'(Behold!) Mesopotamia was called wisdomliterature in which good and bad,Whoevertakes a (false)oath inthe presence of this deity, herepresentedas humans, animals, andvarious objects, appearas active figdoes not survive anymore!"'(KUB54.1;my translation differs ures opposing each other. Animalsin many cases from that ofand inanimate objects are depictedin the form of a clerihew as imbecilicArchi and Klengel 1985).Biblical Archaeologist, June/September1989

beings, short of wit, and lacking theability to reason. They can only usetheir instinct, whereas humans areendowed with wisdom and insight(Hittite, hattatar; Hurrian,madi-). Agreedydeer,for example, is comparedto an ambitious governor.The literary theme in these pieces is, again,liberation, release from evil (paratarnumar;Neu 1988a: 10),and perhaps the reestablishment of primarydivine orderon earth. Whether theyplayeda part in magical rituals or festivals (perhapsnot unlike Illuyankain the purulli-festival)is not clear.Both Hittite and Hurrianversions revealmeticulous efforts tostructure the composition, whichindicates that they are not merescribal exercises but first-class literary exemplars.They are designatedas "song,poetry"(SIR),and both contain traces of well-organizedverse,which can be observedin Hattictexts as well (KUB38 p. ivf., "GruppeII";Haas and Thiel 1978:66-90).Groups of stories all seem to have asingle author, as the narratorintroduces successive stories with thewords, "Iwill put aside this story(literally,words)and will tell youanother."This is important in regardto the individual authorship of literary works, although, unfortunately,in general the authors did not signtheir names (see Guterbock 1978:213). Evidently,as with the laterHomeric epics, the literary devicesused by these authors were not oftheir own invention but were takenfrom the vast resources of an evergrowing folklore tradition.The following passage, in whichan analogy is made between an ungrateful copper cup and a man'sson,will

311), among them a sensational tab- let made of bronze that was found underneath the paving stones along- side the inner city walls near Yerkapi (Neve 1987a: 405; Otten 1988, 1989). We can say very little about the physical structures in which the Hittites kept and stored their tablets. At