Transcription

Smart choices for citiesMaking urbanfreight logisticsmore sustainable

Smart choices for citiesMaking urban freightlogistics more sustainable2

Smart choices for citiesMaking urban freightlogistics more sustainableTable of ContentsPreface. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5Summary. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7Urban freight logistics: scope and definitions. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9Complexity of urban freight logistics. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9Different ways for action: policy, technical and logistics . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10Impacts and challenges. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11Stakeholders in urban freight logistics. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12Different relations between supply chain actors . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13Overview of successful measures . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17Stakeholders’ engagement. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17Regulatory measures. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21Market-based measures. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 28Land use planning & infrastructure measures . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 35New technologies. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 44Eco-logistics awareness raising. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 48Conclusions. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 54References . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 57Web references. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 603

Smart choices for citiesMaking urban freightlogistics more sustainable4

Smart choices for citiesMaking urban freightlogistics more sustainablePrefaceThe objective of the CIVITAS WIKI project is to provideinformation on clean urban transport and the CIVITASInitiative to European city planners, decision-makers andcitizens. With its policy notes WIKI wants to inform people incities on a number of topics that currently play an importantrole in urban mobility.Among the different components of urban mobility, urbanfreight logistics is in fact traditionally considered as theleast sustainable because of its evident negative impacts(generating noise and pollutant emissions, increasingcongestion and posing a threat to the safety of road users).That is why it is necessary to encourage the reflection uponthese issues, the sharing of experiences and best practicesbetween cities and the raising of awareness among decisionmakers in order to trigger alternative, and more sustainable,approaches to urban freight planning.This fifth policy analysis focuses on the topic: ‘Making urbanfreight more sustainable’.Freight distribution is a vital part of life in modern citiesand plays a relevant role within the whole urban mobilitysystem. Although urban freight systems have not receivedmuch attention to date, actual demographic trends showingan increasing urbanization, together with the pervasiverole of information and communication technologies andthe consistent growth of e-commerce are bound to posefurther challenges to the urban freight system.Eight policy analysis will be produced by the CIVITAS WIKIproject team. Topics can be proposed by cities via theCIVITAS secretariat or through the CIVITAS thematic groups.So if you have a topic you want to know more about, pleaselet us know!We hope you enjoy reading this policy note,The CIVITAS WIKI teamThis publication was produced by the CIVITAS WIKI consortium. The policy note was compiled by Tito Stefanelli (TRT), CaterinaDi Bartolo (TRT), Giuseppe Galli (TRT), Enrico Pastori (TRT) and Hans Quak (TNO). Special recognition is due to Mike McDonald(WIKI advisor), Tariq van Rooijen (TNO) and Cosimo Chiffi (TRT) for the review of the manuscript and to Ivan Uccelli (TRT) for theinfographics. Last but not least, a special thanks to Simone Bosetti (TRT) for his valuable coordination of the entire working staff.5

Smart choices for citiesMaking urban freightlogistics more sustainableSummaryThe note provides a general overview of urban freight issues,definitions, the scope of the subject, and indications of futuretrends. The note focuses on providing evidence to supportthe activities of actors and stakeholders when making crucialdecisions on, and planning for, urban freight logistics.Freight distribution is an increasingly important part ofmodern city life.Most goods consumed in our cities originate externally andthe transport elements within the cities are often referredto as the “last mile” in the supply chain. Trucks remainthe dominant transport mode as they are perceived to bemost suitable to move goods between specific origins anddestinations within the complex urban grid of streets.A selection of measures is presented to offer a variety ofpossible solutions to be implemented by local small- tomedium-sized European cities in order to achieve moresustainable urban freight transport. The goals are to “reducethe use of conventionally fuelled vehicles in urban traffic andto achieve essentially CO2-free city logistics in major urbancentres by 2030” as set out in the White Paper 2011.However, trucks generally have significant environmentalimpacts such as CO2, NOX, particulates (PM10, PM2.5,PM1), and noise emissions. Traffic safety and parkingrequirements for delivery vehicles are also of concern.While greenhouse gas emission effects are felt on a globallevel, others are felt locally. For urban areas the last mileposes the greatest problems for the environment, customers/citizens and logistics service providers. Therefore, promotingand sustaining alternative and sustainable strategies andsolutions suitable to the urban environment is a critical aspectof urban transport planning.This note offers a toolkit of possible and tested solutionsto city decision-makers and planners. It is not intended asan exhaustive document treating all aspects of the freightsystem.This policy note is a concise document intended for widedissemination within the CIVITAS community to raiseawareness and increase knowledge of urban freight issuesand challenges.6

Smart choices for citiesMaking urban freightlogistics more sustainableIntroductionUrban freight traffic accounts for about 10-15% of kilometrestravelled1 and emits approximately 6% of all transportrelated GHG emissions2. It accounts for between 2% and5%3 of the total workforce employed in urban areas andit is estimated that between 3% and 5%4 of urban land isreserved to logistics activities 5.An increasing number of people order goods via the Internetwith growing frequency9. In 2013 a report by the EuropeanCommission10 stated that “almost half of EU citizens (45%)say they have shopped online in the last 12 months.”It is very likely that in 2015 the equivalent numbers will beeven larger.Some 20-25% of freight vehicle kilometres isgoods leaving urban areas, and 40-50% isincoming goods. The remaining percentageinternal exchange (i.e. goods having both theirdestination within the city)6.related torelated torelates toorigin andBy 2025, cities are likely to be larger (60% of the world‘spopulation is expected to live in cities), information andcommunication technologies (ICTs) will be pervasive (morethan 80 billion connected devices), and the online retailsector will have risen to nearly 20%11 of total retailing.The following estimates of goods generated in an urbancontext have been deduced from studies and analysesconducted for several urban areas:The trade-off between the economic advantages of anefficient and effective urban freight system and the variousenvironmental disadvantages which may be generated to thedetriment of the population is becoming ever more critical.However, there is a general lack of detailed knowledge andactions to address issues relating to urban freight logisticsby urban authorities, and of the practical opportunities forimprovement which exist. 0.1 delivery/pick-up per person per day; 1 delivery/pick-up per economic activity per week; between 300 and 400 freight vehicle trips per 1,000persons per day; and The reason for this is that the rules governing the transportof goods are different from those affecting the transportof people. Evidence shows that the principles underlyingthe transport of goods are mainly those of a competitivemarket among logistics operators based on trying to meetincreasingly stringent performance requirements (in terms ofquality and timing of the services offered). It can be arguedthat the resulting apparent neglect of the freight sector isdetrimental and disadvantageous for many actors andstakeholders: thanks to a deeper knowledge and involvementby public parties, activities and processes could be furtherimproved and made more efficient with significant benefitsnot only for operators but also for citizens and all otheractors and stakeholders in cities.between 30 and 50 tonnes per person per year7.Certain emerging global trends will significantly change thelogistics sector paradigm and its internal mechanisms.More and more people live in cities. Applying the Degreeof Urbanization classification (DEGURBA classification),in 2012, 200 million Europeans “were living in denselypopulated areas”8. While a growing population offersan opportunity for urban areas to thrive and for risingprosperity, the problems posed by logistics will increasewithout radical change.During the first three rounds of the CIVITAS Initiative12, 44urban freight logistics measures were developed in 30 citiesto tackle problems caused by freight deliveries. Urban freighttransport measures in the first two rounds of the programmehad a high failure rate which was identified as being map/urban2White Paper, 20113Macario R., 20124Macario R., -map/urban9Morganti et al. -map/urban10EC, 20137Dablanc, 200911Frost & Sullivan, 20148EU, 201412CIVITAS I, CIVITAS II and CIVITAS PLUS.7

Smart choices for citiesMaking urban freightlogistics more sustainableto an inappropriate approach to the involvement of privatecompanies and a lack of support and commitment fromother stakeholders. In the third round, CIVITAS PLUS, betterresults were achieved, but it was again demonstrated thatstakeholders (local businesses and delivery companies)needed to be involved early in the process if success was tobe possible.It is evident that no single solution can address and solve allurban freight transport problems. What is needed to makeurban freight more sustainable is an appropriate blend ofdifferent initiatives and measures. This note should help cityauthorities to identify the blend most appropriate for them,but does not claim to be an exhaustive document treating allaspects related to the freight system.This note is aimed at raising awareness and increasingknowledge of urban freight issues and challenges amongpolicy makers. The document can be considered to be atoolbox of the most relevant initiatives and measures fromboth CIVITAS and other EU experiences.Measures and initiatives are organised and presented forpolicy makers to draw on for ideas and suggestions to betransferred to their specific contexts. Measures have beengrouped into six categories of initiatives: stakeholderengagement, regulations, market-based initiatives, landuse planning, new technology-driven measures and “ecologistics” awareness-raising measures.It is intended to help decision-makers of small-/medium-sizedEuropean cities to identify smart urban freight strategies totackle major challenges affecting city liveability, includingissues relating to mobility, social inclusion, and economicwealth. These challenges differ from city to city not only inrelation to whether they are present, but also in relation totheir mix and their level of influence (i.e. their related effects).The policy note offers city authorities and planners a toolkitof possible and tested solutions available to be implementedin their city, together with an indication of potential positiveand negative impacts. A straightforward transfer of asolution from one city to another is not always feasible, sobeing aware of all the implications of a measure is of vitalimportance for a better outcome.8

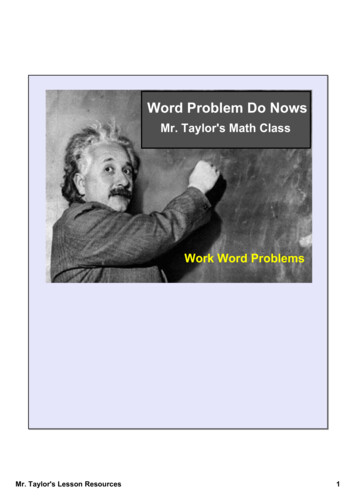

Smart choices for citiesMaking urban freightlogistics more sustainableUrban freight logistics:scope and definitionsComplexity of urban freight logisticsThere is no common definition of urban logistics. In literaturevarious terms are used to refer to the general concept ofthe transportation of goods and waste in urban areas;“urban goods movement”13, “city logistics”14, “urban freighttransport”15. The exact definitions of these terms differ slightlyas to what is included and what is not.Although the definition is simple, it includes a huge varietyof very different transport operations and logistics activitiesand requirements. The only common factor is that they takeplace in an urban area (geographical aspect) and concernthe movement of goods (transportation aspect) and servicerelated trips by commercial entities (commodity aspect; i.e.transport of things as distinct from people17).A simple definition16 of freight transport in cities is: allmovements of goods in to, out from, through or within theurban area made by light or heavy vehicles, including servicetransport and demolition traffic as well as waste and reverselogistics. Household purchasing trips are not considered tobe part of urban freight transport as these are considered tobe passenger transport trips.Market sector of urban freight transport, AustriaTech (2014)nnwaste disposal servicesrecycling materialsnnnnnnWASTEnnnRETAILwaste disposalservicesutility servicesgardening servicesnnnCONSTRUCTIONAND ROADSERVICESnnnnfood productsbeveragesfast food deliverieslaundry servicescity distributionfood productsmilk deliveriesbakery productsgoods on palletsbeveragesEXPRESS,COURIERAND POSTnnpostal and packagedeliveriescity distributionparcelsgoods on palletsmoney deliveriesHOTEL, RESTAURANTAND CATERING Austria Tech, Based on DG Move, 201213Ogden, 199214Taniguchi et al., 200115Allen et al., 200016179Based on Alice, 2014; Lindholm, 2013see also Verlinde, 2015

Smart choices for citiesMaking urban freightlogistics more sustainableUrban freight logistics can “be classified by transport mode,type of operator, and origin of goods (the goods can comevia a long-distance supply chain, or be part of a very localexchange between a shipper and a receiver)18”, or by sectorserved. Furthermore, the vehicles used are also very diverseand include, for example, large trucks, vans and cargobikes. In addition, a distinction can be made between freightthat is handled by companies for their own account or bylogistics providers on behalf of third parties. Examples ofthe former include instances where the transport is operatedby manufacturers with their own employees and fleet, byretailers with their own vehicles to supply the store from adistribution centre, or by retailers making home deliveriesto final customers such as small retailers or pharmacies.Examples of the latter include a professional carrier, aregistered freight or logistics operator operating on behalfof a shipper, for example postal and parcel companies orlogistics service providers. Technical: determines on the one hand the availablemeans (e.g. vehicles) involved in urban freight transportand on the other hand the means to plan trips andcommunicate (e.g. ICT).Logistics: determines the operational conditions forurban freight transport trips, e.g. exact location, deliveryhours, delivery frequency, means used, etc.Together, these three perspectives of action determine theactual organisation of the different urban freight transportoperations, based on the operational conditions and theavailable means. These three different perspectives foraction also correspond to the different stakes the variousstakeholders have in urban freight transport.The organisation of urban freight transport operationsOrganise urban freight transportas efficiently as possible within boundaries(e.g. policy, supply chain, commerce)Another way to classify the different forms of urban freighttransport is by sector served (i.e. “the market sector of urbanfreight transport”)19. Five sectors can be distinguished: i)retail (including e-commerce), ii) express, courier and post,iii) hotel, restaurant and catering (Ho.Re.Ca.), iv) constructionand v) waste.Adding vi) offices and vii) service-related trips to these sectorsgives a fair picture of the main freight transport activitiestaking place in cities. The organisation of logistics, and as aresult of urban freight transport, differs between (and within)these sectors.LOurban freighttransportoperationsTECPolicy: determines the urban conditions in whichurban freight transport operations can take place (time,location, etc.).Dablanc, 200919MDS, 201220Quak, 2014IC T10HNICALAnother way of classifying the urban freight transport fieldis by differentiating between perspectives of action20. Ingeneral, there are three different ways for action to makechanges to (a part of) the urban freight transport system:18SMix determinesDifferent ways for action: policy, .technical and logistics GISTICVE HIC L E SPOLICY

Smart choices for citiesMaking urban freightlogistics more sustainableImpacts and challengesHowever, small- or medium-sized cities have some conditionsthat are favourable in relation to urban freight logistics.Citizens’ perception of, and involvement in, city life isdifferent, and citizens are generally more active in mediumsize urban contexts as compared to larger ones. Greaterinvolvement means that attitudes are often more pronouncedwith more immediate reactions to policies and measures. Inaddition, in small- or medium-sized cities, the flow of goodsis often easier to control, and access restrictions can bemanaged more readily due to the limited number of accesses.Due to its high level of complexity, urban freight logistics haseconomic, environmental and social impacts as cities areconfronted with more traffic, congestion, noise and pollution.Root causes for these problems range from inadequate roadinfrastructure and inefficient logistics processes resulting froma low load factor to unnecessarily long dwell times and/orhigh numbers of individual deliveries.The relevance of these impacts varies according to city size,and there are differences between large conurbations andsmall- or medium-sized cities. The latter are particularlyaffected by urban freight transport. Narrow roads and a lackof loading and unloading areas within city centres combinedwith inefficient logistics processes produce negative effectsthat are attributable to the small scale of these cities. Inaddition, small- or medium-sized cities usually have a lowerfinancial investment capacity and, due to their dimension,the critical mass for innovation is more difficult to reach.There is often a lack of detailed data of exactly what types ofurban freight transport activities and trips take place in cities.Vehicle and traffic data is usually available, but it appears tobe quite difficult to relate this to the various logistics activities.Moreover, the huge complexity and heterogeneity of urbanfreight transport makes it complicated and difficult to definetransport policies targeted at urban freight.Impacts of urban freight logistics, AustriaTech (2014)ECONOMIC IMPACTSENVIRONMENTAL IMPACTSSOCIAL IMPACTSIMPACTS OF SCALEroad congestionpollutant emissionsphysical consequencesof pollutant emmissionson public healthfew resourcesinefficiencyuse of non-renewablefossil-fueltraffic accidentslack of co-operationsweste of resourcesland and aggregatesnoiseless policy considerationswaste productionvisual intrusionfew logistics providersbased in citiesother quality of life issueslittle infrastructure Austria Tech11

Smart choices for citiesMaking urban freightlogistics more sustainableStakeholders inurban freight logisticsUrban freight transport is characterized by the presence ofmany stakeholders. The main reason for this is that it takesplace in the city – the central location where flows andactivities intersect. Firstly, the supply chain actors, who areresponsible for sending, carrying and receiving goods aredistinguished21 2122The supply chain actors and the specific relations betweenthe shipper, carrier and receiver together determine thelogistics activities. To influence urban freight transport by wayof policies, it is necessary to understand these relationshipsin order that the right stakeholders are addressed, i.e. thestakeholders who are able to make a change (see nextsection: different relations between supply chain actors).The urban logistics activities are constrained by severalboundary conditions, as well as by the means available,such as vehicles or loading/unloading areas.shippers – manufacturers, wholesalers, retailers, etc.Shippers send goods to other companies or persons andare often not located in the city; as a result they usuallydo not feel responsible for urban freight transport issues.They tend to maximise their levels of service in termsof costs and reliability of transport. In many casesthe shipper is the stakeholder responsible for hiring acarrier.On the one hand policy boundaries by public authoritiesdetermine the urban freight transport possibilities. Wedistinguish the following public stakeholders: the localgovernment, the national government, and for some issueseven the European Commission (e.g. setting EURO-standardsfor truck engines). The local authorities focus on an attractivecity, and from that perspective urban freight transport can beconsidered as a main contributor of nuisance and pollution.On the other hand, securing city accessibility and havingan effective and efficient transport system is also one of thelocal authorities aims. Local authorities are interested in thereduction of congestion and environmental nuisances as wellas in increasing safety of road traffic. The local authoritiesoften consider the urban transportation systems as a whole.And from that perspective the local authorities aim atresolving conflicts between the stakeholders, i.e. the supplychain actors, the urban traffic and the residents.transport operators – freight carriers, couriers, etc.Transport operators usually aim at minimising their costsby maximising the efficiency of their pick-up and deliverytours, and they are expected to provide a high level ofservice at low cost. There is a trade-off between a highlevel of service and the efficiency of freight vehiclesloads. Transport operators are the stakeholders carryingout urban freight transport, but in many cases they arerestricted by boundaries set by others; for example,opening hours of stores or designated time windows tomake the deliveries. Transport operators are often activein a geographically larger area than the city.receivers – shopkeepers, offices, construction sites,residents, etc. Receivers are located in the urban areasand are mostly the endpoint of the logistics chain.Receivers are often not responsible for urban freighttransport since shipments are organised and paid forby the shipper (so for the receiver the transport priceis included within the price of the ordered goods). Inmany cases receivers do not realize that they can anddo influence urban freight transport by, for example,setting time windows. However, as the receiver is oftenthe only supply chain actor located in the city, they canbetter identify with local issues than transport operatorsand shippers who are usually active across a largergeographical area.National authorities are usually only marginally involved inurban freight transport as it is mainly seen as a local matter.However, the interests of national authorities (such as reducingcongestion and externalities at a national or regional level)affects many urban freight transport operations as well aslocal authority policies.Other boundaries for urban freight transport result from theavailable infrastructure set by resource supply stakeholders.There are three different resource supply stakeholders22:infrastructure providers, infrastructure operators (managers),and landowners. These stakeholders and their investmentsdetermine the possibilities for urban freight transport.following MDS, 2012 and Verlinde, 2015MCD (2012)2212MCD (2012)

Smart choices for citiesMaking urban freightlogistics more sustainableDifferent relations between supply chain actorsFinally, there is a group of actors who are affected by urbanfreight transport, but who do not directly influence or affectit: the impactees23. Local authorities often act on behalf ofthese impactees as these are the actors who vote in localelections, and as a result focus on minimising the real andapparent problems caused by urban freight transport. Theseimpactees include: The classification of supply chain actors into shippers,carriers and receivers simplifies the private-sector part ofurban freight transport. However, in order to make effectivepolicies, it is important to realize that there are majordifferences in the relationships between these supply chainactors, which result in variations in decision-making power.other traffic participants – this group consists ofvulnerable road users (cyclists and pedestrians) thatshare the same infrastructure as freight transport vehiclesespecially in the urban area, and of passenger vehiclesthat are (sometimes) hindered by double-parked trucksinvolved in loading and unloading at the kerbside oron the road.As urban freight transport manifests itself especially intransportation in the urban area, one might be inclined tofocus on the carriers since these actors are operating thevehicles. However, in many cases, those driving the vehicleshave the least decision-making power of all supply chainactors. For example, the carriers are paid by the shipperswho can determine the delivery conditions, and the receivers(e.g. shop owners) determine with their opening hours whena carrier can deliver.city residents and city users – the people who live,work, and shop in the city. Residents can experiencenuisance by urban freight transport (e.g. smell, noisenuisance, or vibration).The following example illustrates two types of shipper-carrierreceiver combinations. Although both a retail chain and anindependent retailer are receivers in the urban area, theydiffer considerably. And with that their stakes in urbanfreight transport issues differ as well24. A large retail chain issupplied differently from a small retailer (see figure below).visitors / tourists – who are affected by urbanfreight transport only to a minor degree, although onecould argue that (too many large) trucks in a city centrecause visual intrusion or decrease the perception of thespatial quality of the city. Especially from a commercialpoint of view, having an attractive city (centre) whichtourists and visitors want to visit is important, and thereis therefore an interest in minimising nuisance by urbanfreight transport.Transport is usually carried out by different types of carriers:private carriers and for-hire carriers, respectively.People who suffer the negative impacts of urban freighttransport are also often benefit from it as they are often thefinal customers of the products and services delivered (e.g.retail, Hotels, Restaurants & Cafés - Ho.Re.Ca., etc.).Other stakeholders are the providers of vehicles, informationtechnologies (IT) support systems, and other means thatenable especially supply chain actors and public authoritiesto fulfil their roles in urban freight transport.2324Ogden, 1992; Quak,

Smart choices for cities Making urban . 200 million Europeans “were living in densely- . urban freight more sustainable is an appropriate blend of different initiatives and measures . This note should help city aut