Transcription

Fish identification tools forbiodiversity and fisheriesassessmentsReview and guidance for decision-makers585ISSN 2070-7010FAOFISHERIES ANDAQUACULTURETECHNICALPAPER

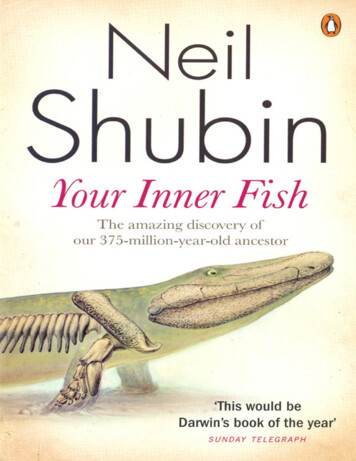

Cover illustration:Mosaic by Johanne Fischer

Fish identification tools forbiodiversity and fisheriesassessmentsReview and guidance for decision-makersEdited byJohanne FischerSenior Fishery Resources OfficerMarine and Inland Fishery Resources BranchFAO Fisheries and Aquaculture DepartmentRome, ItalyFOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONSRome, 2013FAOFISHERIES ANDAQUACULTURETECHNICALPAPER585

The designations employed and the presentation of material in thisinformation product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoeveron the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations(FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, cityor area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers orboundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers,whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these havebeen endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similarnature that are not mentioned.The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) anddo not necessarily reflect the views or policies of FAO.ISBN 978-92-5-107771-9 (print)E-ISBN 978-92-5-107772-6 (PDF) FAO 2013FAO encourages the use, reproduction and dissemination of material in thisinformation product. Except where otherwise indicated, material may becopied, downloaded and printed for private study, research and teachingpurposes, or for use in non-commercial products or services, provided thatappropriate acknowledgement of FAO as the source and copyright holder isgiven and that FAO’s endorsement of users’ views, products or services is notimplied in any way.All requests for translation and adaptation rights, and for resale and othercommercial use rights should be made via www.fao.org/contact-us/licencerequestor addressed to copyright@fao.org.FAO information products are available on the FAO website (www.fao.org/publications) and can be purchased through publications-sales@fao.org.

iiiPreparation of this documentThis document is a result of the contributions and deliberations of the workshop“Fish Identification Tools for Biodiversity and Fisheries Assessments” (Vigo,Spain, 11–13 October 2011) convened by the University of Vigo and the FAOFishFinder Programme. Although not a “Proceedings” as such, it does reflect thepresentations and discussions of participants regarding user perspectives and userrequirements, definition of criteria for the characterization of identification tools,description of identification tools and scenarios as well as recommendations forresearch and development. However, it also contains observations and summariesadded after the workshop with the intent to make this document more accessibleto the reader. A draft version of this document was circulated to workshopparticipants, and this finalized version incorporates substantive comments andcorrections received from them.The workshop participants consisted of 15 invited experts from 10 countries,two FAO officers and one FAO consultant. The first part of the workshop wasdedicated to 14 plenary presentations on fish identification methods and tools. Theworkshop then proceeded to provide definitions for the criteria used to characterize each identification tool addressed by the workshop. Each expert reviewed thesummary description and visual characterization of the ID tools prepared by FAOand the workshop then evaluated the results in a non-comparative manner. It wasagreed that the visual characterization would serve as an approximate qualitativeindication of the strengths and weaknesses of each method. After the workshop,a comparative review was undertaken by the editor and some adjustments weremade to the figures.The subsequent development and description of relevant scenarios took placein three subgroups: one focusing on research and development, the second onconservation, responsible use and trade, and the third on education, awarenessbuilding, consumer considerations and non-consumptive uses. The scenarios wereintended to illustrate a variety of user requirements for species identification andrecommending appropriate identification tools for each of these scenarios. Theworkshop concluded with a statement containing a number of recommendationsby workshop participants.The papers contained in Annex 3 to this work have been reproduced as submitted by the participants, without editorial intervention by FAO.

ivAbstractThis review provides an appraisal of existing, state-of-the-art fish identification(ID) tools (including some in the initial stages of their development) and showstheir potential for providing the right solution in different real-life situations.The ID tools reviewed are: Use of scientific experts (taxonomists) and folklocal experts, taxonomic reference collections, image recognition systems, fieldguides based on dichotomous keys; interactive electronic keys (e.g. IPOFIS),morphometrics (e.g. IPez), scale and otolith morphology, genetic methods (Singlenucleotide polymorphisms [SNPs] and Barcode [BOL]) and Hydroacoustics.The review is based on the results and recommendations of the workshop“Fish Identification Tools for Fishery Biodiversity and Fisheries Assessments”,convened by FAO FishFinder and the University of Vigo and held in Vigo, Spain,from 11 to 13 October 2011. It is expected that it will help fisheries managers,environmental administrators and other end users to select the best available species identification tools for their purposes.Fischer, J. ed. 2013.Fish identification tools for biodiversity and fisheries assessments: review andguidance for decision-makers. FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Technical PaperNo. 585. Rome, FAO. 2013. 107 pp.

vContentsPreparation of this documentAbstractAcknowledgementsAbbreviations and acronymsiiiivviiviiiRecommendations11. Introduction32. User perspectives72.12.22.3Fish taxonomy in biodiversity and fishery assessment andmanagementA fishery inspector’s view of fish identificationIdentification and commercial names of fishery products:a view from the industry7893. Species identification tools113.13.23.3Species ID tools included in this reviewCriteria for the evaluation of species identification toolsEvaluation of species identification tools3.3.1 On-site taxonomist3.3.2 Local (folk) expert3.3.3 Local reference collection3.3.4 Image recognition system3.3.5 Field guides based on dichotomous keys3.3.6 Integrated Photo-based Online Fish-Identification System(IPOFIS) exemplifying Interactive Electronic Keys (IEKs)3.3.7 IPez (morphometric software)3.3.8 Scales3.3.9 Otoliths3.3.10 Genetic identification through single nucleotidepolymorphisms (SNPs)3.3.11 Genetic identification using barcoding3.3.12 Acoustic fish identification1112131313141516Web-based fish identification and information resources223.4171718191920214. Selecting an identification tool254.14.225252828282929UsersSelection criteria4.2.1 Response time4.2.2 Accuracy4.2.3 Resolution4.2.4 Type4.2.5 Resources

vi5. Description of 5.235.24Catch reporting by fishers (logbooks)Assessment of introduced fish species in a lakeMonitoring catch during exploratory fisheryReporting catches of lake fisheries (exotic species)Reporting catches of marine artisanal fisheriesFingerlings of aquaculture species are correctly identifiedby suppliersReduction of bycatch through pre-harvest surveyPort inspections of fishery catchesVessel inspection on the high seasLive fish inspection by customs (CITES)Verification of origin of catchesFish product inspection by customs (CITES)Distribution and characteristics of populationsProvision of data for the ecosystem modelling of livingmarine componentsDevelopment of application to distinguish living objectsfrom submarinesFish inventory for gear development to minimize bycatchChanges in species diversity due to climate changeTaxonomic training of studentsAnglers track the spread of aquatic invasive species (AIS)Assessment of genetically modified fish in waters and marketsCorroboration of the geographic origin of fishes as documentedin catch certificateTraded fish is labelled correctlyInvestigating the alleged presence of exotic and GM speciesDivers identify marine organisms343535363637373838393939404041414242436. Conclusions45Annex 1 - List of participants47Annex 2 - Workshop agenda49Annex 3 - Participants’ contributions51

viiAcknowledgementsCástor Guisande (Professor of Ecology at the University of Vigo) has been animportant driver for the work presented here. Without his personal commitment,enthusiasm and important contributions to the workshop in Vigo this work wouldnot have been possible.Sincere gratitude is extended to all experts (see Annex 1) whose knowledgeand informed discussions at the meeting created the substance of this publication and many of whom travelled to Vigo from far-away places. In particular,these are: Nicolas Bailly, Alpina Begossi, Gary Carvalho, Juanjo De la Cerda,Keith Govender, John K. Horne, Ana L. Ibáñez, Sven O. Kullander, John Lyons,Jann Martinsohn, Ricardo da Silva Torres, Paul Skelton. John Horne is especiallyacknowledged for expertly chairing the meeting.Devin Bartely’s (FAO Senior Fishery Resources Officer) great support throughout the planning and execution of the workshop as well as while developing thisTechnical Paper is greatly appreciated. Much is also owed to Edoardo Mostardaand Peter Psomadakis (FAO Consultants for Fish Taxonomy) for their invaluablereviews of the document at different stages.Monica Barone (FAO consultant) and Kathrin Hett (Associated ProfessionalOfficer at FAO) are thanked for their significant input and assistance in the planning phase of the workshop and development of the agenda. Monica also helpedrunning the workshop, ensured that all records and outputs were saved and accessible and prepared a first outline of this document.Elisa Pérez Costa (Junior Research Assistant, University of Vigo) and LuigiaSforza (FAO Office Clerk) assisted in the meeting preparations and providedlogistical support to the workshop which was much appreciated by all. Last butnot least, Julian Plummer and Marianne Guyonnet are thanked for their meticulousproofing of the document.

viiiAbbreviations and acronymsAISaquatic invasive speciesBMUBeach Management Unit (Kenya)CBDConvention on Biological DiversityCBD-GTICBD-Global Taxonomy InitiativeCITESConvention on International Trade in Endangered Speciesof Wild Fauna and FloraCoFCatalog of FishesCoLCatalogue of LifeFCOfisheries control officerGMgenetically modifiedIDidentification (tool)IEKinteractive electronic keyIPOFISintegrated photo-based online fish-identification systemIRSimage recognition systemIUUillegal, unregulated and unreported (fishing)NGOnon-governmental organizationRFMOregional fisheries management organizationSNPsingle nucleotide polymorphismUNEP-WCMCUnited Nations Environment Programme – WorldConservation Monitoring CentreWoRMSWorld Register of Marine Species

1RecommendationsAt the conclusion of the workshop “Fish Identification Tools for Biodiversityand Fisheries Assessment”, held in Vigo, Spain, from 11 to 13 October 2011, theparticipants prepared the following statement and recommendations.In recent decades, biodiversity research has been prioritized and new fishidentification techniques have been developed. However, the actual transfer andapplication of fish identification technologies in projects and management schemeshas lagged. It is an important objective of the present document to encourage andpromote the informed use of appropriate identification techniques in all areas,specifically:r Take initiatives to strengthen the links and enhance communication betweenscientists, stakeholders and end users.r Strengthen the taxonomic community through additional trainingopportunities, the creation of jobs for taxonomists, research funding andinfrastructure to ensure the stability of nomenclature and development ofreliable diagnostic data sets.r Strengthen the fish identification expertise of officers and others who needto identify fish in the execution of their jobs in order to ensure that theidentification is authoritative and current.r Develop more local, scientifically reviewed and curated reference collectionsof fish specimens (in fishery agencies, institutes) and encourage their use.r Develop more local, scientifically reviewed and curated fish photographicreference collections (in fishery agencies, institutes) and encourage their use.r Encourage users to assist in the population of reference databases.r Promote the appropriate use of fish identification techniques by publicizingthe range of techniques available to address diverse fishery and biodiversityquestions (promote the right tool for the job).r Encourage collaboration and increased integration of methodologicalapproaches used by taxonomists and other scientists to increase accuracy,repeatability and the creation of enhanced tools.r Improve access to fish identification tools.r Make available more open-access fish identification tools or tools in the publicdomain.r Create central repositories of metadata (e.g. web-links, experts) and/orclearing houses.r Develop and improve identification tools for early life history stages ofaquatic organisms.r Strengthen the development of new and user-friendly fish identification toolsthrough improved investment.r Develop legally binding standards and guidelines for fish identification forfishery compliance purposes.r Make available primary data (such a barcodes and images) that supportdevelopment and maintenance of automatic and semi-automatic identificationtools for improved cost-effectiveness.

2Fish identification tools for biodiversity and fisheries assessmentsr Ensure that scientific documents report on the species identification methodsthe authors have used.r Increase awareness among the public and policy-makers of the importanceof accurate fish identification through the use of user-friendly media andadvocacy.r Identify and address gaps in information for the identification of aquaticspecies.

31. IntroductionThe current review intends to provide an overview of existing, state-of-the-art fishidentification (ID) tools (including those in the initial stages of their development)and to show their potential for providing the right solution in different real-lifesituations. The content of this review is based on the results and recommendationsof the workshop “Fish Identification Tools for Fishery Biodiversity and FisheriesAssessments”, convened by FAO and the University of Vigo and held in Vigo,Spain, from 11 to 13 October 2011. It is expected that the review will help fisheriesmanagers, environmental administrators and other end users to select the bestavailable species identification tools for their purposes. The experts involved in thisreview also hope that it will help renew public interest in taxonomy and promotethe need for taxonomic research including user-friendly species ID tools.Although the need for taxonomic expertise has never been as pronounced as itis today, this has not translated into training more taxonomists and providing morefunding for necessary developments in taxonomy. Instead, more and more individuals without a taxonomic background, such as fishery inspectors and observers,customs officers, data collectors, traders and others, have been tasked with thecomplex and often difficult assignment of identifying aquatic species. These lessexperienced users are often faced with confusing and inadequate information onthe species they encounter and how to identify them reliably. Products such as thespecies catalogues and field guides produced by the FAO FishFinder Programmecan help in countries and regions for which they exist, and web resources, suchas FishBase1 and the Catalog of Fishes2 offer guidance to resolve issues regardingthe correct scientific name for a species. Nonetheless, greater efforts are needed toensure a correct identification of aquatic resources under management and conservation regimes.In recent decades, many new and promising techniques for the identificationof fishes have emerged, in particular based on genetics, interactive computer software, image recognition, hydroacoustics and morphometrics. However, with fewexceptions, such advances in academic research have not yet been translated intouser-friendly applications for non-specialists and still require further investmentsto mature into globally applicable tools.Public consciousness about the need to conserve biodiversity has recently beengrowing. In all parts of the world, policy-makers, funding agencies and scientistshave made it a priority to advance policies and knowledge for this purpose. Thisinterest was prompted by the realization that taxonomic resources around theworld are declining at a rapid pace and that this is having a negative impact onhuman well-being and survival.The Census of Marine Life3 has just finished an ambitious and large-scaleten-year project that includes an inventory of aquatic species. A number of largenational and international funding organizations (Convention on BiologicalDiversity [CBD],4 DIVERSITAS5, European Environment Agency,6 EuropeanCommission,7 Global Biodiversity Information Facility,8 Global Ocean u/http://ec.europa.eu/index en.htmwww.gbif.org

4Fish identification tools for biodiversity and fisheries assessmentsSystem,9 Intergovernmental Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services,10International Union for Conservation of Nature,11 United Nations EnvironmentProgramme – World Conservation Monitoring Centre [UNEP-WCMC]12 andmany others) are currently supporting broad worldwide attempts to summarize allknowledge on aquatic organisms and provide global species inventories (All CatfishSpecies Inventory,13 Continuous Planktonic Recorder project,14 UNEP-WCMCSpecies Database,15 Fish Barcode of Life Initiative16 and Marine Biodiversity andEcosystem Functioning EU Network of Excellence17 among many others). TheFAO Commission on Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture18 has been mandated to cover all components of genetic resources relevant to food and agriculture,and it is now preparing a global review of aquatic resources.The CBD uses the following definition: “‘Biological diversity’ means the variability among living organisms from all sources including, inter alia, terrestrial,marine and other aquatic ecosystems and the ecological complexes of which theyare part; this includes diversity within species, between species and of ecosystems”.19This definition clarifies that biological diversity does not only apply to the numberof species in an ecosystem but also considers the difference between subspecies,populations and other meaningful units below the species level.The CBD-Global Taxonomy Initiative (CBD-GTI)20 recognizes a “taxonomicimpediment” to the sound management of biodiversity consisting in “the knowledge gaps in our taxonomic system (including those associated with genetic systems), the shortage of trained taxonomists and curators, and the impact these deficiencies have on our ability to conserve, use and share the benefits of our biologicaldiversity”. The CBD-GTI also states that “simple-to-use identification guides forthe non-taxonomist are rare and available for relatively few taxonomic groups andgeographic areas. Taxonomic information is often in formats and languages thatare not suitable or accessible in countries of origin, as specimens from developingcountries are often studied in industrialized nations. There are millions of speciesstill undescribed and there are far too few taxonomists to do the job, especiallyin biodiversity-rich but economically poorer countries. Most taxonomists workin industrialized countries, which typically have less diverse biota than in moretropical developing countries. Collection institutions in industrialized countriesalso hold most specimens from these developing countries, as well as associatedtaxonomic information.”21It has become clear that taxonomic information is not a luxury – it is a real needin a world with a still-growing human population generating enormous pressureon natural resources. More and more organisms are shipped around the world andmarketed continents away from their origins, thus generating an increased needfor global fish identification tools to provide reliable information to consumers,customs officers and fishery inspectors. However, worldwide, there exist rbef.org/www.fao.org/nr/cgrfa/en/CBD, Article 2. Use of l

Introductionthan 32 500 species of finfishes22 and the amount of information required to separate them all is extremely difficult to process; therefore, fish identification is usually conducted at local or regional scales. The increasing globalization of fisheryproducts thus introduces new challenges to the identification of aquatic organisms.In addition, new emerging applications require accurate species identification (e.g.marine hydrokinetic energy and ocean observatories).The collection of species- and population-specific information for the purposeof sustainable fishery management has a long tradition. For many decades, FAOhas been collecting global statistical catch data and analysing the results in two ofits flagship publications: (i) The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture and theReview of the state of world marine fishery resources. While progress has beenmade in the reporting of fishery data, much improvement is still needed for a morereliable and comprehensive assessment of the stock status of many commerciallyexploited aquatic species. Not only the taxonomic resolution of catch data couldbe better for many areas and species, but there is a real concern about the proportion of possible misidentifications in the catch statistics received by FAO, withsevere implications for the ability to manage aquatic organisms sustainably. Withits FishFinder Programme,23 FAO has contributed to improving fish identificationeverywhere and produced more than 200 species identification guides includingtaxonomic descriptions for more than 8 000 species and an archive of more than40 000 scientific illustrations. Although the programme struggles owing to fundingconstraints and competing priorities at FAO, it continues generating products toassist with fish identification in many parts of the world, including the guidanceprovided in this publication.2223The cumulative species description curve for fishes is not yet close to its asymptote and, hence, thenumber of species will continue to increase.www.fao.org/fishery/fishfinder/en5

72. User perspectivesUser considerations provide the background and scope against which thedifferent species ID tools are evaluated. The following summaries describe theuser requirements from three different perspectives.24 The first introduces theviews of a taxonomist and ichthyologist, the second illustrates the difficultiesand urgent needs for correct species identification experienced by a fisheriescontrol officer on the high seas, and the third explains requirements of the fishingindustry and consumers for non-ambiguous species identification and labelling.Notwithstanding the pronounced differences of these three perspectives, they areunified in their conviction that improving the identification of aquatic species willhave considerable positive impacts for biodiversity research, fisheries managementand law enforcement as well as trade and consumer safety.2.1FISH TAXONOMY IN BIODIVERSITY AND FISHERY ASSESSMENT ANDMANAGEMENTA stable naming and indexing system is essential to global communicationabout organisms, and such a system is maintained by the International Code ofZoological Nomenclature. The science of taxonomy, among other things, providesthe methods and the manuals for the identification of organisms. Although largelybased on observations of characters that local fishers may also use, taxonomicresearch offers the tools for a regionally and globally valid identification. Someexamples of fundamental taxonomic tools for the use in fisheries include FishBase25,the book Fishes of the North-eastern Atlantic and the Mediterranean26and a seriesof catalogues and regional checklists provided by FAO.27 Although surveying,mapping, taxonomic characterization, and naming of the global marine andfreshwater fish fauna are fundamental to a healthy fishery, the importance oftaxonomic work is not fully recognized in the fisheries sector, particularly notin the boreal regions where “everything is known”. However, a lack of pertinenttaxonomic information or lack of user experience can actually or potentially lead toundesired consequences for fishery management, and fish taxonomists are urgentlyneeded to provide reliable name standards and identification tools for fisherypurposes.In many regions of the world, fish stocks are being exploited without muchtaxonomic assistance. However, it is impossible to develop conservation plans andlong-term management without knowing what species are involved, and preferablyalso whether subpopulations exist, and how to identify them. Important faunalguides have been published by South Africa, Japan and Australia, but in theseregions new species continue to be discovered, both from fresh material and fromold museum specimens.Taxonomic resources may also play a role in prospecting for new resources asis done particularly in aquaculture. Involving taxonomists in aquaculture is alwaysrecommended in order to prevent expensive errors based on the erroneous identification of species, e.g. to avoid a “new” species being imported to locations whereit (or a very similar form) already exists but is known under an incorrect name.24252627See Annex 3 for full papers submitted by workshop participants.Froese, R. & Pauly, D., eds. 2013. FishBase [online]. [Cited 19 June 2013]. www.fishbase.orgWhitehead, P.J.P., Bauchot, M.-L., Hureau, J.-C., Nielsen, J. & Tortonese, E., eds. 1984–86. Fishesof the North-eastern Atlantic and the Mediterranean. Paris, UNESCO.See www.fao.org/fishery/fishfinder/publications/en

8Fish identification tools for biodiversity and fisheries assessmentsA mistaken identification, the use of outdated names, or the application ofmisleading names can have considerable economic consequences; therefore, trustand reliability are essential attributes for taxonomic experts and taxonomic tools.However, taxonomy is often practised by people without the necessary training,not least persons only interested in naming new species. Ideally, a taxonomic expertshould hold a PhD in systematic biology including training in nomenclature andalpha taxonomy and should have considerable prior experience with the speciesgroup in question.Many users of taxonomic services consider a photograph sufficient to work on.That may sometimes be true, but it may also turn out to be a bad cornerstone inan operation involving considerable sums of money. Specimen and DNA samplesshould be adequate for the level of precision required for the identification, andthat usually entails more than a snapshot taken on a rocking ship.In conclusion, taxonomy is paramount for describing biodiversity but it isunderfunded. Precise identification of species and populations can be effected byseveral tools, and this is necessary for fishery management plans and reporting.2.2A FISHERY INSPECTOR’S VIEW OF FISH IDENTIFICATIONFisheries enforcement around the world is unique to its own area of operations.The task faced by a fisheries control officer (FCO) is a mammoth one. Therefore,FCOs will develop their skills in accordance with the fishing activities of theirrespective countries. Some of the duties that FCOs are responsible for are asfollows:r monitoring and recording fish landings in commercial and fishing harbours;r monitoring slipways where recreational boats land their catches;r conducting coastal patrols (land patrols on foot or by vehicle);r conducting aerial patrols;r conducting fisheries patrols at sea by means of inshore and offshore patrolvessels;r effecting arrests of illegal, unregulated and unreported (IUU) fishers andfishing vessels;r collating evidence;r identifying fish;r testifying in court;r obtaining statements from expert witnesses such as scientists in areas of fishidentification;r assisting investigators with cases;r ensuring continuous follow-up on the outcomes of their respective cases.In order for an FCO to ensure effective enforcement of fisheries regulations, it isessential for the FCO to have an understanding of fish identification. Fish identification is important in fisheries enforcement, and the ability to identify fish is of criticalimportance as it will assist in strengthening the case of the FCO against the accused.However, there exists a lack of training in the field of fish identification for FCOs,and many FCOs do not possess this skill. The lack of the necessary tools and experience in the field of fish identification is a crucial factor that needs to be addressed.

User perspectives2.3IDENTIFICATION AND COMMERCIAL NAMES OF FISHERY PRODUCTS:A VIEW FROM THE INDUSTRYToday, the correct identification of fish species and their precise, updated andtaxonomic ordering are the basis for the bulk of

5.10 Live fish inspection by customs (CITES) 36 5.11 Verification of origin of catches 37 5.12 Fish product inspection by customs (CITES) 37 5.13 Distribution and characteristics of populations 38 5.14 Provision of data for the ecosystem modelling of living marine components 38 5.15