Transcription

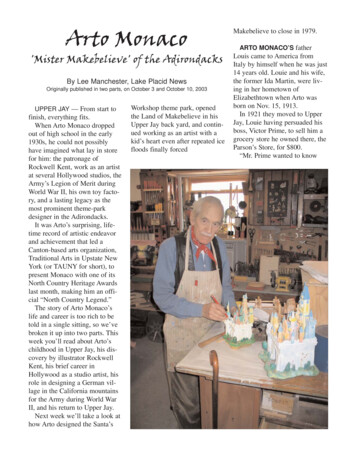

Arto Monaco'Mister Makebelieve' of the AdirondacksBy Lee Manchester, Lake Placid NewsOriginally published in two parts, on October 3 and October 10, 2003UPPER JAY — From start tofinish, everything fits.When Arto Monaco droppedout of high school in the early1930s, he could not possiblyhave imagined what lay in storefor him: the patronage ofRockwell Kent, work as an artistat several Hollywood studios, theArmy’s Legion of Merit duringWorld War II, his own toy factory, and a lasting legacy as themost prominent theme-parkdesigner in the Adirondacks.It was Arto’s surprising, lifetime record of artistic endeavorand achievement that led aCanton-based arts organization,Traditional Arts in Upstate NewYork (or TAUNY for short), topresent Monaco with one of itsNorth Country Heritage Awardslast month, making him an official “North Country Legend.”The story of Arto Monaco’slife and career is too rich to betold in a single sitting, so we’vebroken it up into two parts. Thisweek you’ll read about Arto’schildhood in Upper Jay, his discovery by illustrator RockwellKent, his brief career inHollywood as a studio artist, hisrole in designing a German village in the California mountainsfor the Army during World WarII, and his return to Upper Jay.Next week we’ll take a look athow Arto designed the Santa’sWorkshop theme park, openedthe Land of Makebelieve in hisUpper Jay back yard, and continued working as an artist with akid’s heart even after repeated icefloods finally forcedMakebelieve to close in 1979.ARTO MONACO’S fatherLouis came to America fromItaly by himself when he was just14 years old. Louie and his wife,the former Ida Martin, were living in her hometown ofElizabethtown when Arto wasborn on Nov. 15, 1913.In 1921 they moved to UpperJay, Louie having persuaded hisboss, Victor Prime, to sell him agrocery store he owned there, theParson’s Store, for 800.“Mr. Prime wanted to know

Scale model of “Annadorf,” the Bavarian village Monaco built in the San GabrielMountains above Los Angeles as a training ground for soldiers preparing to invadeEurope during World War II.where Dad was going to get themoney from,” Arto wrote 3 yearsago in a short biography of hisfather, “and he said that hethought Mr. Prime would loan itto him.“Mr. Prime said, ‘You knowsomething, somebody that’s gotthe arrogance to ask him to sellhim the store, then ask me for themoney to pay for it — I amgoing to let you have it.’ “Louie was quite an entrepreneur, opening a garage thatcatered to bootleggers, then arestaurant.“Dad was funny — he was likea comedian. Directors, producers,movie stars and songwriters — alot of well-known people cameup for dinner at Louie’s,” Artowrote. “They’d come at 6 o’clockat night, and they’d stay until 1o’clock in the morning.”ONE OF THOSE celebrityguests at Louie’s Restaurant wasRockwell Kent, probably thebest-known illustrator of his day.Kent lived on Asgaard Farm, outside Au Sable Forks, where hehad his studio.Arto, then in his mid-teens,had been put to work paintingmurals for his father’s eatery.Only one of his murals from thatperiod still survive. It can still beseen through the window of thevacant storefront nearest to theMain Street bridge on the southside of Au Sable Forks. Thestorefront once was Quirk’s sodafountain, then the Village Inn. Allthe people pictured were wellknown local folk of the day.“I was doing very poorly inschool,” Arto recalled. “RockwellKent admired the murals that Ihad on the walls. I went down tosee him one day, and Rockwellsaid that he thought that I couldbe an artist. I said that my fatherwanted me to be a lawyer, andmy mother wanted me to be adoctor. I knew that I couldn’ttake school any longer, and Iwanted to quit. Rockwell talkedto Dad and con-vinced him that Ishould be an artist.”Through his network offriends, Kent got Arto enrolled atthe Pratt Institute, a prestigiousart school in Manhattan. Arto’sroom and board cost 15 a week;his tuition, 120 a year (it’s 22,196 for the current year).While attending Pratt, a friendof Arto’s complained to himSgt. Arto Monaco, center with cigar, shares a beer and a joke with men from hisU.S. Army Signal Corps Training Division unit in California during World War II.

about “having to go to themovies all day every Saturday,”Arto recalled in a recent interview. “I asked him what waswrong with that!”Arto’s friend’s mother was amember of the Hays Committee,a moral watchdog that ratedmotion pictures, much liketoday’s Motion PictureAssociation of America.“He took me to meet his mother. They wanted a younger person on the committee to eventhings out, so I got on,” Artosaid.For the next two years Monacospent his Saturdays in a specialscreening room watching sevenor eight movies every week.“They’d give us these cards tofill out after each one, and forevery one I’d write, ‘Great picture.’ I found something good inevery one of them,” Arto said.By the time Monaco graduatedfrom Pratt in 1937, he was morethan ready for a career as a studio artist in Hollywood.MEMBERS OF the summercrowd that frequented Louie’sRestaurant in Upper Jay helpedArto find work in Tinseltown,Robert Besanceney, of Buffalo, was 3years old when he visited the Land ofMake-believe during its opening seasonin August 1954.The Castle and three storybook cottages at the Land of Makebelieve in the 1950s.first at MGM, then at WarnerBrothers, then Paramount, thenDisney, then back at MGM, all inrapid succession. A nighttimedrive through the desert endedseveral days later in Upper Jay.“I was restless,” Artoexplained with a shrug to AnneMackinnon, a local writer, for a2001 article in Adirondack Lifemagazine.After another intervention fromone of the summer-celebritydenizens of his father’s restaurant, Arto was asked over to ahouse in Jay where JohnSteinbeck and director LewisMilestone were working on storyboards for “Of Mice and Men.”The result: Arto went back toHollywood and MGM, where hestayed until 1941. Havingreceived a draft notice, Artodecided to enlist before his callup date. Doing so would givehim a little more leverage as tohis assignment — or so hethought.Arto ended up in boot camp onLong Island. He graduated todoing busywork at the AberdeenProving Grounds in Maryland,according to Monaco biographerMark Frost, editor of TheChronicle, a weekly newspaperpublished in Glens Falls — untilone day when an NCO asked hisunit if there was anyone whocould paint a sign.Arto raised his hand.“I thought it was going to besomething real important,” Artorecalled, “but it was just a signtelling people not to throw cigarette butts in the urinal.”THOSE SIX “no butts” signsturned out to be more importantthan Arto thought. They broughthis skills to the attention of a

lieutenant who had an idea abouthow to train more soldiers morequickly.“One sergeant was teaching 25men how to put a pistol together,” Monaco said, “but they needed him to train 100 men.”Arto talked with the lieutenant,recalling the illustrations he’dseen in medical texts.“Maybe we could do it thatway, with charts and things,”Arto remembered saying.That was the beginning of theTraining Aids Division, whichstarted with Monaco and oneother man.“That lieutenant was full ofideas,” Arto remembered. “Heasked if we could make a .45 caliber pistol this big,” motioningwith his arms to indicate a handgun about 3 feet long.“Every day it was somethinggreat.”Training Aids grew, little bylittle but steadily, until Arto hadnearly 200 men working for him.Characteristically humble,Monaco claims that the only reason he was in charge wasbecause “I was the first one in,”but the leadership he continuedto demonstrate for the rest of hislife contradicts that.In short order, Private Monacowas promoted to master sergeant,and his unit was transferred outto California, where they set upshop at Camp Santa Anita, formerly a horse track in the SanGabriel Valley outside LosAngeles.With America fully involved inWorld War II, Training Aids hadas much work as it could handle,and more. Its biggest job was thedesign and construction of aBavarian village in the SanGabriel Mountains where U.S.troops could train for the streetfighting that would come onceGermany was invaded.It was named Annadorf “afterthe daughter of one of the menwho worked with me,” Monacosaid. “He was low man on thetotem pole, and it seemed like theright thing to do.”When the war ended, Monacowas given the Army’s Legion ofHonor for his leadership of theTraining Aids Division.And then, he was discharged.‘ALL OF A sudden, you’re onyour own,” Arto recalled. “Aftera few years of the Army regulating every minute of your life,that’s a strange feeling.”Monaco had returned to UpperJay and was working forRockwell Kent, as he had duringcollege, when he received atelegram from his old colonel,Bill James, asking Arto to return

to California. James wanted himto take the skills he’d used inorganizing the Annadorf projectto refurbish a resort developmentin Lake Arrowhead.“The place was like aNormandy village,” Artorecalled. “They wanted me toredo it like a Swiss village.”The job done, Monaco cameback again to Upper Jay.“What I really wanted to dowas put up something likeAnnadorf,” Arto said, “at theFour Corners in Wilmington —but I didn’t have the money. All Icould afford was a restaurant.”Monaco built the Carouselrestaurant, with a circular diningroom, next to a gift shop for hiswife. The Carousel later becamethe Gateway restaurant, whichwent out of business severalyears ago. It was recently refurbished as the Candyman’s fudgefactory and sales outlet.Still restless, Arto took adesign job with Ideal Toys inNew York, but that didn’t lastlong.“I wasn’t there 2 months, and Icouldn’t take that city life,”Monaco said, “so I got my owntoy business going.“That’s how Julian Reissbecame interested in me.”ARTO SET UP a small factoryin Upper Jay where he and hiscrew made simple, durable, colorful educational toys fromwooden blocks for youngsters.That’s where Julian Reiss, theman who came up with the ideafor Santa’s Workshop, came in1949 to ask Monaco to design hisnew attraction.“He described what he wantedto do,” Arto recalled, “and thenhe said, ‘A lot of people wouldthink this is crazy or foolish.What do you think about it?’“I told him, ‘I think it’s beautiful.’ What flashed through mymind in that moment wasAnnadorf — that’s why theNorth Pole looks like it does.“But he was dressed prettyhumbly — I mean, his shoeslooked even worse than mine. Ihad to say to him, ‘Well, Mr.Reiss, I don’t mean to embarrassyou, but this is going to cost a lotof money.’“He said, ‘Well, don’t worryabout that; I can get it. I’ll justtake these drawings you’ve madedown to New York and showthem to my father.’“Mr. Reiss came back the nextday and told me it was all settled— he’d talked to his father, andhe would make the money available. He’d flown his own planedown there.”A few days later Arto, JulianReiss and partner Harold Fortunewere up on Fortune’s tract inWilmington, just below the tollhouse for the WhitefaceMemorial Highway.“We didn’t even have a tapemeasure,” Monaco said. “We justput one foot in front of the otherand walked off the dimensionsfor each building. We had thewhole park laid out in 2 or 3hours, and they were cutting timbers the next day. We had noelectrical engineer, no permits —it was funny.”THOSE WERE the days whentheme parks were sprouting upall over the eastern Adirondacks— and Arto was involved in

A light snow had fallen on the castle at the Land of Makebelieve when it came timeto close on the last day of operations in October 1979designing many of them.Monaco designed a second,smaller attraction for Reiss onthe outskirts of Lake Placid, OldMcDonald’s Farm. Though itstayed open only a few years, itsbuildings formed the core of asummer camp for underprivileged kids from New York Citythat’s run today by the JulianReiss Foundation.The small-scale mill house thatArto designed as part of the entrygate to Old McDonald’s Farm,now half a century old, can stillbe seen in the gully between theTops grocery and SaranacAvenue.By then Monaco had startedthinking about opening up hisvery own park in Upper Jay. Oneday he found himself talkingabout his idea with the father ofKay Cameron, one of his wife’sfriends, who was part owner ofthe J.&J. Rogers plant in AuSable Forks.“I told him I’d like to build avillage for kids to play in,” Artosaid. “It would have very littlethat was commercial about itonce the kids got in, just popcornand soda pop for sale. That’s whyI never made any money — notthat I ever needed money. I’mhappy with what I have.“Anyway, all of that rang truewith Cameron — he hated thosecarnival-type places, selling allthat junk every time you turnedaround. He said he’d pay to buildthe park, and he’d make me pres-ident of the company with 51percent of the stock. Two dayslater we were in the lawyer’soffice, drawing up the papers,and before you know it we’dstarted building.”“Every element bore Monaco’sdistinctive style,” wrote AnneMackinnon about Arto’sMakebelieve architecture,“simultaneously perfect and ‘alittle bit cock-eyed.’ The buildings especially were charmingcaricatures, their slightly exaggerated features — skewedrooflines, emphatic colors, thebric-a-brac of hand-cut shingles— somehow truer than any literaltranslation.”After toying with another namefor his new theme park, Monacosettled on calling it the Land ofMakebelieve. It had a castle, aset of fairytale houses, a riverboat, a train and stagecoach, aminiature town straight out of theOld West, even a fleet of cars thekids could drive around the park— and all of it was scaled to thesize of the park’s young clientele,between 1:2 to 3:4 scale.The children were encouragedto dress up in costumes and playto their heart’s content — andtheir parents were urged to stayout of the kids’ way.“Don’t say ‘Hands Off,’ “ reada sign placed prominently at theentrance to the Land ofMakebelieve, “don’t say ‘Don’tTouch,’ cause no one here forbids, so put your paws on anything — we built this place forkids.”“Arto always said that everychild’s dreams should containmagic castles,” observed BobReiss, Julian’s son, at the

TAUNY award program lastmonth in Canton. “That’s why hemade the Land of Makebelieve.(Arto) didn’t make his art tomake money; he made it to makekids happy.“Arto had no children of hisown, but to every child in the(Au Sable) Valley he was theirUncle Arto, who had the coolestback yard ever.”Indeed, the children of UpperJay were given their own secretentrance to the Land ofMakebelieve, where they couldgo play whenever they wanted —for free.‘THOSE WHO had the goodfortune to visit the Land ofMakebelieve while it was stillopen got a treat they’d never getanywhere else,” Reiss told thecrowd in Canton, reminding themthat Arto’s theme park had beenforced to close down in 1979.The Land of Makebelievestood just a few dozen yardsback from a very shallow stretchof the Au Sable River. The NorthCountry winter froze that riverhard most years. When springcame and the ice broke upstream,it jammed in the Upper Jay shallows. That ice dam pushed thewaters of the Au Sable River outof its banks to cover the nearbyflats, including the field whereMonaco’s theme park was built.In the 25 spring thaws between1954 and 1979, the Land ofMakebelieve was flooded 11times. The last flood was the onethat finally did the park in. Sopowerful was the partly frozenstream that ran through Arto’sback yard that it lifted the park’soffice from its foundations, carrying it about 1,500 feet beforesetting it back down and crushingit.“The Land of Makebelievedidn’t close because it wasn’tdoing a good business,” MonacoThe remains of Cactus Flats in September 2003. What had once been Arto’s own small-scale Western town had become aprivate Western ghost town standing amidst the scrub brush in his back yard — an idea that did not completely displease him.

told Derek Muirden of MountainLake PBS while taping a 1993documentary. “It went out at thetop of its glory. We went outbecause Mother Nature said,‘That’s it, Arto.’ ”Looking around the groundswith Muirden at the remains ofCactus Flats, his child-sizedWestern town, Arto said, “I’ll probably restore some of these buildings — I don’t know what for.”Ten years later, however, anearly 90-year-old Arto Monacoseemed to have resolved himselfto the demise of the Land ofMakebelieve.“The Land of Makebelieve is aplace that once was,” he said in arecent interview, “and it willnever be again. It lives only inthe hearts and minds of thosewho loved it.”1979 flood.Arto has continued giving ofhimself to children. Samples ofhis whimsical furniture can befound in the children’s sectionsof the public libraries in UpperJay and Au Sable Forks.About 10 years ago, Wood andactor-philanthropist PaulNewman roped Arto into paintinga huge mural around the indoorswimming pool of their newcamp for critically ill children,the Double “H” Hole-in-theWoods Ranch in Lake Luzerne.More recently, local developerMickey Danielle persuadedMonaco to design a new children’s camp in Jay for a foundation that had been established byDanielle’s daughter to help thefamilies of children with growthdisorders.“Arto, you’ve made a lot ofpeople happy over the years,”observed Derek Muirden a fewyears ago in a second PBS documentary, “Return to the Land ofMakebelieve.”“Mostly I made myself happy,”Arto replied, “and how manypeople do you know who spenttheir lives doing just what theywanted to do?”ARTO HAS BEEN far fromidle in the nearly quarter centurysince the Land of Makebelieveclosed. He has illustrated some17 books and he’s kept makinggames and toys, the most intricate of them as gifts for hisnephew and niece or friendsaround the Adirondacks — and,sometimes, just because he feelslike it. Many of his toys are keptin the private museum he hasconstructed inside the old shop atthe Land of Makebelieve, nextdoor to his home.Monaco has also kept his handin the theme-park game, helpingout his friend Charlie Wood withdesigns and artwork for his various ventures — Storytown,Gaslight Village and the GreatEscape, where many of the fairytale buildings from the Land ofMakebelieve ended up after theArto Monaco at his 90th birthday party, at the Wells Memorial Library in Upper Jay,on Saturday, Nov. 15, 2003. A few days later he was admitted to the hospital. Hedied the next Friday, Nov. 21, with his family by his side.

Rockwell Kent, probably the best-known illustrator of his day. Kent lived on Asgaard Farm, out-side Au Sable Forks, where he had his studio. Arto, then in his mid-teens, had been put to work painting murals for his father’s eatery. Only one of his murals from that period stil