Transcription

DANCE REVIEW!Intimacy’s Many FacetsJohn Jasperse’s ‘Fort Blossom’ at New York Live Arts!Andrea Mohin/The New York Times"Fort Blossom revisited (2000/12)": featuring, from left, Erika Hand, Lindsay Clark, Ben Asrieland Burr Johnson at New York Live Arts.By ALASTAIR MACAULAYPublished: May 10, 2012The form of dance theater that the choreographer John Jaspersedevelops in “Fort Blossom revisited (2000/12)” is often astonishing.Watching Wednesday’s premiere, I was several times left with thesensation of having traveled to unknown terrain. The piece is anexpanded 70-minute reworking of his “Fort Blossom” (2000). (Weshould not spend time figuring out what the title might mean.)“Fort Blossom revisited” features four performers who remainonstage more or less throughout, and it’s constructed according tobinary principles. The two women (Lindsay Clark and Erika Hand) areelegantly dressed in long-sleeved short red dresses, with subtly

matching lipstick. The two men (Ben Asriel and Burr Johnson) are,however, naked. For a long period the women are together on the left,the men on the right. The dualism that develops between their twodifferent worlds is extraordinary.Something they do have in common is transparent vinyl inflatables.The two women have matching amber boxlike ones on which they sitand which they later wear on their backs like wings. Initially on theright there is a single large inflatable, like a small see-through Li-Lo:which, several inches thick, is for a long while all that separates thetwo men, as one lies horizontally on top of the other. The two men, inprofile to us, move their pelvises in rhythm. We’re watching adeconstruction of anal sex. The balloon, by separating their twobodies, has the effect of objectifying the movement. Then, after theyhave lain in stillness for a long, long while (itself an amazingspectacle), they deflate it until it is just the sheath between them. Bythe time they finally separate and peel it away, it’s become a metaphorfor a condom.It’s conventional — and often true — to say that the effect ofpresenting a performer naked onstage is to de-eroticize the body. Butthe erotic suggestiveness of Mr. Jasperse’s movement makes this scenefar more complex; I imagine most viewers find, as I did, that the eroticand nonerotic aspects of the scene keep changing.There follows a slow male duet that is often even more mesmerizing —and yet more astounding. Only once do the two men hold each other’seyes; only once, I think, do their naked groins meet. But their intimacyof contact is amazing. The cheek of one man’s face is pressed tenderlyto the cheek of the other’s buttock. One man crouches on all fourswhile the other arches right back on top, lying on him back to back.Most of these positions and movements would count for little if theywere danced with clothes on, and for less if performed by man andwoman. Here, and especially because of the slowness, they become arare form of drama.Something else happens during all this: which is that our perception ofand response to the body itself continually develops, alters, shifts. As

these men part their legs, shift their pelvises, ripple their spines,there’s little we don’t know about their groins. And their bodies as awhole keep taking on new looks as we go on watching. It helps thatMr. Asriel’s soft-muscled body is unlike the firmer definition of Mr.Johnson. The flow of lines in the abdomen, the back, the pelvis, the legis wholly dissimilar in each case — and marvelously absorbing.The duets for the women, though less enthralling, are more dancy andhave a wry formality, not without absurdity (those balloons), thatmakes a perfect contrast to what’s happening between the guys on theright. The women bend their spines, they extend their legs, theysustain specific arm positions, and yet there’s a quality ofpedestrianism to all they do.Later the two couples meet. Some of this involves a happy sense ofplay — as the women thwack the men with those balloons, they keepredirecting them — and some of it involves more conventionallychoreographic patterns, groups, lines. Yet conventionality has beenremoved by the nakedness of the two men. Arabesques, tilts of thetorso, semicircular swings of the leg — these are simply not the samewhen two of the pelvises involved are naked.It’s very possible that “Fort Blossom revisited” would be largelyunremarkable if all four performers wore the same clothes. I refer to itas dance theater, but should I? Its four performers are certainlytrained dancers, sometimes delivering academic dance position andsteps, often showing evident physical control. But the steps don’t buildinto much by way of phrases; dancing itself seems to be deconstructedhere. Yet meanings, ideas, contrasts, drama, keep growing as youwatch. Dance, the body, and erotics are topics about which “FortBlossom revisited” keeps testing, investigating and analyzing, andoften brilliantly. Leaving the theater we are no longer quite what wewere when we arrived.“Fort Blossom revisited (2000/12)” runs through Saturday at NewYork Live Arts, 219 West 19th Street, Chelsea; (212) 924-0077,newyorklivearts.org.!

ARTSJOURNALSearch the site .DanceBeatDeborah Jowitt on bodies in motionBlurring ThresholdsJune 2, 2014 by Deborah Jowitt — 3 CommentsJohn Jasperse brings diverse sources and his own history into a bold new work at New York Live Arts,May 28 through 31.John Jasperse’s Wi thi n between . Standi ng: Burr Johnson and Maggi e Cl oud.

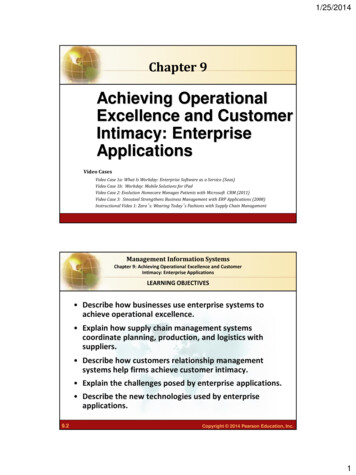

O n fl oor (L to R): Si mon Courchel and Stuart Si nger. Photo: Y i -Chun WuJohn Jasperse is not the kind of choreographer who draws a movement style out of his own body andsensibility and sticks with it. He reacts to ideas floating around in the culture, queries his own practice,tries something he hasn’t tried before. Often the movement he creates with and for his dancers isfunctional, whether the task at hand is moving books around, as it was in a scene in his 1997 Waving toYou from Here, or sliding one naked body over another, as in his Fort Blossom (made in 2000, revised in2012). He littered the stage with plastic bottles and other detritus in Misuse liable to prosecution (2007)and broke the famed fourth wall in Prone (2009) by having audience members lie on rows of clearplastic mattresses while performers danced strenuously over and between them.His new Within between, which premiered at New York Live Arts, is by far the danciest work of his thatI’ve seen. The stage is a pristine arena for it. Lenore Doxee, who created the lighting and visual design(the latter in collaboration with Jasperse), has covered the white floor with an green grid of differentsized rectangles; on either side stand two large, wall-high white blocks. The four dancers—MaggieCloud, Simon Courchel, Burr Johnson, and Stuart Singer—initially wear snappy, variously patternedblack-and-white outfits (briefs and shirts for the men, a short-skirted dress for Cloud); later, theyexchange these for wildly colorful clothes that explode with floral or geometric motifs.Stuart Si nger (L ) and Si mon Courchel carry Burr Johnson i n John Jasperse’s

new work. Photo: Y i -Chun WuThere is only one prop, but it’s a humdinger. Courchel begins by walking onto the stage and picking upan exceedingly long, slim, flexible pole. With immense care, he inserts it into the first rows of theaudience (no one appears to wince or shrink away), chooses a seated target, and slowly makes the polestroke its way from the person’s shoulder, over his/her head, and down to the other shoulder. He doesthis to two spectators. Think about the title of the piece. “Within” and “between” do not constitute apolarity; they probe (like the pole) at such concepts as inner feelings, relations among individuals andwithin a group, and mediation between artistic styles. Courchel’s act, with nice irony, sets the stage forboth intimacy and distance.The adventures of that pole call to mind the maneuvers in Trisha Brown’s 1973 Sticks, in which (usually)four women, keeping the ends of their longish sticks connected in one wobbly line, moved from lyingbeneath the sticks to stepping up and over them and returning to their initial positions. Jasperse,choreographing for four dancers and a single pole, may be alluding to Brown’s work, while referencingthe task structures of his own plain early works and the barre that dominates a ballet class; in theprocess, he creates an imaginative and understatedly virtuosic sequence.Singer joins Courchel for a duet in which together they shoulder the rod and, in unison, maneuver it inincreasingly daring ways; now it’s on their shoulders, now it’s resting on the toes of their outstretchedfeet, now it’s caught on the crooks of their bent knees.It’s at this point that a plucked string breaks the quiet and is followed by soft humming, sounds of athroat being cleared, a brief “okay.” Jonathan Bepler’s score for Within between is a marvel—full ofmysteries, quietly chaotic. Sometimes it’s hard to tell which sounds are recorded and which are beingproduced by the four musicians, who sit close to the front row of spectators with their backs to us. MickBarr and Eric Hubel are guitarists, Megan Schubert is described in the program as an “experimentalvocalist,” and Bepler is adept on a number of instruments. The recorded music features numerousartists—most prominently, the Ohio State Marching Band and Claude Debussy’s “Clair de Lune,”recorded by pianist Jean-Efflam Bavouzet, the latter work at times transformed and merged with othersounds.The voices escalate from whispers and become both more urgent and more organized, as Cloud andBurr join the other two dancers. At first these newcomers, standing, execute slow balances, whileCourchel and Singer continue their adventure with the pole, but before long, the four have moved intodouble duets, and pole-bearing becomes a shared or exchanged job.

L to R: Burr Johnson, Si mon Courchel , Stuart Si nger, and Maggi e Cl oud i nWi thi n between . Photo: Y i -Chun WuOne of Jasperse’s sources is ballet. While “Clair de Lune” plays for the first time, the performers stand ina diagonal line and, in unison, perform simple, precise balletic moves without a barre (the pole has beencarried away). But the classical look briefly turns cranky. A curved arm angles itself, a pointed footclubs, and sights and sounds become spookily disfigured. As the dancers move smoothly throughmaterial that has the look of a pre-ordained ritual, they gaze out of the corners of their eyes and dragdown one corner of their mouths. Percussion patters in, strings get harshly strummed, and Doxsee turnseverything red for a while.The complexity of these conjunctions among sound, motion, light, and color increases, and the dancers(who are credited as collaborators in the choreography) expand the range of their movements, whilealso occasionally referring back to moves they’ve made before (what Courchel had the pole do in theway of a caress, for instance, can be replicated by a hand moving over a colleague’s head). The lighting,which has turned several of the rectangles on the floor yellow, then made the back wall green, givesJohnson and Singer the brightest of stages when they stop jiggling against each other and take offleaping across it.Without warning, another reconfigured movement source crops up as the dancers move from two-partcounterpoint into unison and advance on us, spraddle-legged and slapping their thighs and bodies

rhythmically. The allusion may be to step-dancing, but it has none of that African-American form’slooseness-within-precision and jazzy edge. It also calls to mind the diverse ancestors of Stepping, likethe Gumboots dancing of South Africa, and has a distant kinship with some Pacific Islanders’ stampingand clapping. But quickly it allies itself with the other elements in this community’s vocabulary,including the shifty gazes, the askew lower lip, and other facial expressions. At one point, Courchel andSinger carry on with the clapping and stepping and slapping, while Cloud and Johnson embark on whatcould (almost) pass for a slow-motion balance exercise in a ballet class.John Jasperse’s Wi thi n between . Front: Si mon Courchel and Maggi e Cl oud.Back (L to R): Burr Johnson and Stuart Si nger. Photo: Y i -Chun WuI should emphasize that none of these borrowings seem eclectic; Within between is no postmodernpastiche in which anything can go with anything. It’s as if all the sourced material has been made intocommunal property and re-modeled according to the values of an open-minded society. The crossoverfootwork that often figures in Stepping mates with ballet’s croisé positions and anyone’s maneuvers ina cramped space. At one point the music—a strongly rhythmic orchestral segment—sounds as if KurtWeill might have been composed it, but didn’t. At other times, it evokes a barnyard or a clutch ofgossiping neighbors. The dancers (by now in their bright-colored attire) may leap about and performother handsomely athletic steps, but with differences in timing and space patterns.Other elements enter. Suddenly, the dancers are all smiles; “what fun this is!” they appear to tell oneanother. Singer and Courchel perform together for a while with their eyes shut. Singer then begins to

talk, describing in an undertone the movements that they’re doing—a cliché unpacked from the earlydays of postmodern dance.Within between is a wondrous work, made all the finer by the expertise and expressiveness of allinvolved. You can’t conveniently liken it to a patchwork quilt or a photo album or a collage. All thememories, styles, and structural ideas have been merged into an intriguingly original work, theirdiversities absorbed and re-imagined by Jasperse and the very individual performers. Embodimenttakes on a new power. Within what and between what delineate a landscape of possibilities.You Might Also LikeWhere Do You Plan To Travel?Balanchine and Massine at American Ballet Theatre

danceviewtimeswriters on dancingJune 03, 2014A Different Kind of Pole Dance“Within between”John JasperseNew York Live ArtsNew York, NYMay 28, 2014by Martha Shermancopyright 2014 by Martha ShermanBeautiful is not what one expects from John Jasperse’schoreography. Challenging and energizing, yes; but beautiful, not somuch. In “Within between,” he intentionally upended his ownhistory and habits, partly by using classical movement as alaunching point for a work that cleverly wove his four exceptionallytalented dancers in formal choreographed movement. Then,winking, he intruded on that formalism with idiosyncratic tags of hisown. The result was a gloriously danced, beautiful piece aboutshifted expectations. It was laced with humor, unexpected twists,and a powerful instinct for reaching out and pulling the audience infrom the first moment to the last.Photo Ian DouglasSimon Courchel, Stuart Singer in “Within between”That magnetic pull came not just from the dancers, but from the music as well, performed live by four musicians, includingthe score’s composer Jonathan Bepler. As they settled themselves downstage, dancer Simon Courchel moved to the center ofthe green graph-lined stage, carrying a 25’ thin metal pole. He walked deliberately toward the audience, the pole pointingdirectly into the group. Until the very last moment, no one expected to actually be touched, but that was precisely whathappened. Courchel lowered the pole on to the shoulder of a patron in an upper row (the sharp intake of the audience’scollective breath, audible with surprise) then dragged it back down, lightly touching others. At one point, he moved the pole’stip slowly from the left shoulder of one hapless fellow, outlining his head, then resting on his right shoulder.Having literally broken through to the audience, Courchel was joined by Stuart Singer, who stood downstage and became thetarget of the pole drawing. Courchel outlined Singer’s head and body; then the long metal rod connected their bodies, as theycontrolled it with small muscle movements, allowing it to roll down their extended legs and to their feet and toes. They movedto the floor and began their pole duet in earnest, arms and legs curling around the pole to create angled geometric poses, asBepler’s score shifted with each scene from buzzes, pops and plinks, to giggles and vocalizations (“it’s okay” “oh my God.”)Maggie Cloud and Burr Johnson joined the pole duet as standing partners. Though mismatched in height (Cloud isdiminutive; Johnson looms above her) their well-synched leaps and arabesques were like the upper deck to Courchel andSinger’s floor duet, until all four stood and morphed into a quartet at a ballet barre. The pole, which had slid to the ground

and eventually was pulled off the stage, was there in spirit, and the four moved through class ballet exercises, lovely tendus,arabesques, and port de bras, to taped music that had been woven into the live score. Debussy’s “Claire de Lune” was entirelyin keeping.Jasperse’s use of a quartet of three men and one woman kept theclassical movement from being typical; he didn’t choose the usualtwo couples. Having moved through a series of perfect poses,suddenly mid-jeté, more traditional expectations were shattered, asthe dancers’ faces twisted into gurns, with thick protruding lipsjutting diagonally down. Their eyes, up to now calm and neutral,widened and bugged out – in shock or surprise, as their posescrinkled, arms and hands twisted, fingers wriggled in a kind of antiballet. It took very little to twist the classical to the contorted.Photo Ian DouglasSimon Courchel, Burr Johnson, Maggie Cloud in“Within between”In the opening scenes, the dancers were all costumed in black andwhite stripes of plaids, and the stage was lit brightly, the green gridlines the only outlying color; later they changed to wildly colored,mismatched costumes of clashing colors and patterns, a signal thatthey were no longer bounded by formalism.As the score moved between sounds and words, music and noise, the dancers moved from balletic leaps and twirls tosquatting, thigh-slapping hiccups of movement, their facial expressions and the details of their moves never predictable. Mostof “Within between” was danced on a diagonal slashing across the stage, including the pole dance duet and the quartetdancing as a pair of duets, or entering and exiting along the longest possible angle. Again, the strength of the line felt formal;when the dancers broke free, (in a few scenes where they were not partnered, or in a parade of trios in a later scene) it wasbracing.Each duo had a personality of its own. Courchel and Singer used long leg extensions to swivel along the floor, later into amore approximate duet, warily circling, approaching and falling back from each other. The relationships were cemented,though, as the four moved in and out of mixed trios, one dancer off stage as the other three created their specific connection,then the offstage dancer replacing one onstage, until all four had rotated with each other.When Cloud was in the trio, she was the lightest to lift and swing over two sets of shoulders; when the men danced, theymoved as a closely bound threesome, but with weightier shifts and lifts. Yet not always: when we got used to the weight,Singer did a bright cartwheel over the other two. As the trios wove in and out, the dancers were increasingly loose and themovement relaxed, though rigorous. Eventually all four danced together. They hopped, hit their knees, arms flipped aroundand clapped each others’ shoulders; a few fleeting smiles escaped – this was fun, and their enjoyment was palpable.Finally, the quartet faded offstage. Courchel and Singer, having been our opening guides, returned to end the piece. Theireyes were closed and they murmured to each other, first inaudibly, then we could hear their instructions (“let hands wiggle,”“raise arm and put on my head.”) Although they obeyed, each interpreted the rules slightly differently, and their movements,though synched, were no longer intent on perfect alignment. Their final instructions, before leaving the stage, were forthemselves and for us, too: “Open my eyes.” “I watch, I look.” They were worthy reminders from a striking performance.copyright 2014 by Martha ShermanPosted at 10:56 PM in Martha Sherman Permalink

MY PROFILERegisterReview: Humor and athleticism in Jasperse pieceShareShareLoginShareShareJul. 10, 2014 @ 10:57 AMBy Susan Broili; special to The Herald-SunSubmitted Yi-Chun WuSubmitted Yi-Chun Wu. Maggie Cloud, Simon Courchel, Burr Johnson and Stuart Singer in John Jasperse's "Within Between."DURHAM — If you want an hour in the theater to pass quickly, spend time with work by modern dance choreographerJohn Jasperse. The American Dance Festival premiere of his ADF-commissioned work, “Within Between,” offered amemorable evening on Tuesday at Reynolds Industries Theatre.A score of varied sounds and music, lighting in bright, tropical hues, movement by turns classical and modern,and use of humor sustain interest.The first moments make it clear that this will be no ordinary experience. The dance begins with the house lights

up and French dancer Simon Courchel carrying a very long, metal pole as he walks toward the front of thestage. There’s dramatic tension and nervous laughter as he keeps going until he reaches the edge of the stageand his pole extends to the third row of the audience. It looks like he’s being careful not to poke anyone but healso doesn’t seem in any hurry to withdraw the pole.In the next section, this pole plays an integral role in the choreography as dancers balance it while at the sametime creating a seamless flow of movement. They support the pole as they crouch, stand and swivel. Whenthey roll like logs on the floor, the pole rolls right along on top of them without falling off. There’s also suspensewhen the pole begins rolling down a dancer’s leg and it looks as if he won’t be able to keep it from crashing tothe floor. But at the last minute, he flexes his foot forward and catches it.The pole balancing also includes a funny moment when Courchel, Burr Johnson and Stuart Singer walk in a lineas they balance the pole on one shoulder. When Maggie Cloud attempts to join them, she’s too short to supportthe pole. So, she stands on her toes so her shoulder makes contact and stays on her toes to walk with theothers. Humor seems to be a rare commodity in modern dance, so it’s especially delightful when achoreographer uses it so well.In the rest of the dance, movement includes some classical ballet. One classical-looking pose may be satiricbecause the raised hand gesture – fingers spread wide and extremely articulated – seems overly dramatic.Other times, quirky moves pop up. A dancer bends forward, thrusts both arms between her legs, sticks herhands out and wriggles her fingers. Another time, a dancer’s arms go rag doll limp and flap from side-to-side ashe vigorously twists his torso.Dancers provide their own music as they stamp their feet, clap their hands and slap their bodies. Other musicincludes Claude Debussy’s “Claire de Lune,” bluegrass and a marching band. Then, there’s spoken word bothrecorded and live. The live speaking occurs in the last section in which two men describe what they are doingsuch as “I drop my arm.” Other times, what they are doing suggests that one’s interest in the other is notreciprocated. One man says, “I crawl away from you quickly.” The other man says, “I watch you.” Then the firstman says, “I go” and walks offstage as the dance ends.WHAT'S THIS?AROUND THE WEBNewsmax HealthThe Motley FoolZagatAlzheimer’s Is NowEpidemic. Know the5 Early SignsWarren Buffett TellsYou How to Turn 40 Into 10 Million50 Best Pizzas inAmerica: One fromEvery StateLifefactopiaMust HaveAppliances Beingsold For Next To

Fort Blossom Revisited – an essay by SuzanneCarbonneauPosted January 28th, 2012 at 3:34 pm.In this head the all-baffling brain,In it and below it the making of heroes.—Walt Whitman!John Jasperse is a distinctly philosophical choreographer. His dances have served aspotent vehicles for existential exploration, posing a series of thorny questions that veryoften lead to thorny conclusions. He has shown nerves of steel in following theseinquiries from work to work, wherever they might lead and however disquieting theinvestigation proves to be. Jasperse has proved so indispensable an artist preciselybecause he insists on examining those issues that make us most uneasy. In directingus to look in those places we might naturally shy from, Jasperse has served as truthteller in an era when the very notion of truth seems endangered by ideology,benightedness, and wishful thinking.Jasperse recognizes that discomfort is triggered by what is unknown and that theaesthetic remedy is to spelunk where the caves are darkest and deepest. Afflict thyself,might be his motto. Jasperse’s dances lodge in those places others flee: habitually, hebegins by forcing himself to examine a subject or condition that he himself findsdisturbing. Indeed, Jasperse imagines that it is the responsibility of the artist to engagein psychic dumpster diving, with the artist’s consciousness as first mark. In addition tothe difficult content, he complicates matters with the admonition that he also face theaesthetic unknown. In continuously reimagining the tradition he has been handed,Jasperse engages with another kind of tradition—the avant-garde charge that the artistmuscle ahead of the culture, bringing back discoveries to share with viewers and notinfrequently disconcerting them in the process. “If I give an audience an experiencethey’ve already imagined,” Jasperse declares, “then I’m not doing my job.” Discomfitinghimself, discomfiting us. It’s double-barreled target-practice.This revival of Fort Blossom is no exception. Once again, Jasperse is an aestheticfireman, running toward the conflagration. In this work, Jasperse has challenged himselfto re-examine notions concerning the fundamental stuff of dance: the body andmovement. He begins by foregrounding body parts usually subsumed in western dance:the back, the soles of the feet, the genitalia. In Fort Blossom, Jasperse pays specialattention to the buttocks and its interior. The resulting movement redefines beautyentirely: celebrating inelegance, awkwardness, unexpectedness. And in the process,Jasperse reveals just how profoundly concert dance—even in its contemporaryexperimental manifestation—is snared in unexamined premises about its own nature.Outsiders might be forgiven for assuming that, as an artform centered in the sensuous,professional dance practice is inherently erotic. But as Jasperse says, dancers “havebeen trained to compartmentalize” their bodily experiences. In fact, in American moderndance sexuality is implicitly banished from the studio, just as medical doctors, forexample, are trained to objectify what might arouse others. It is characteristic of

Jasperse, however, that he does not allow even these basic assumptions to gounchallenged. How well does this work in practice, he wondered? And where does theviewer fit into the schema?In Fort Blossom revisited 2000/2012, Jasperse faces these issues with characteristicmettle and candor—examining the body as it has been the subject of art history, ofpornography, and of clinical study. These are questions that Jasperse has been tacklingsince he first made his international reputation with Excessories, a work he creatednearly two decades ago. But the acclaim it brought was paradoxical. Jasperse hadcreated Excessories in reaction against the uneasy relationship that theatrical dancehad with its audiences. He was troubled that there was a “pornographic vision” beingapplied to concert dance—that is, spectators could objectify the fit young bodies ofperformers while cloaking prurience under the guise of art. In response, Jaspersebrought the lascivious subtext into the open, challenging himself to use nudity andsadomasochistic conventions to reveal the reality of the theatrical transaction. WhileJasperse’s critique in Excessories was extraordinarily legible, many viewers brushedthis reading aside in favor of the opportunities for further titillation that the dance offered.In a way, Jasperse realized, Excessories had backfired. Or so he then thought.A commission to work in Israel got him rethinking whether Excessories actually hadmiscarried its mission. At the Batsheva Dance Company, Jasperse discovered a cultureunlike that in experimental American dance. Among the Batsheva dancers, there waslightness and a sense of play around sexuality, and the dancers allowed naturaleroticism into their experience of artmaking. Jasperse drew the lesson that the diligentcreation of aesthetic form and content is an invitation to the viewer, but that he could notcontrol the response of his audiences. They would bring their own desires, intentions,and critical processes to the work he presented. And Jasperse began to regard this notas the problem he had imagined it to be in Excessories, but as inherent in theexcitement of artmaking.He determined again to tackle the questions he had raised in Excessories, but this timemore plainly and aggressively. The result was Fort Blossom. In creating the originalversion in 2000, Jasperse employed the nudity that had proved so vexing inExcessories, but, with his newly found acceptance of perceptual differences, in a moredirect and pointed way. In acknowledgment of the troubled history around the femalenude in western art and pornography, where women have been objectified, co-opted,and consumed, Jasperse reversed expectations. He divided his cast by gender: themen would be naked, the women would be clothed. And he embedded this dichotomy inthe movement, structure, and design of the entire work, bifurcating the compositionalstrategies and stage space, devising an antinomic title.As he worked on Fort Blossom, what Jasperse found of interest, however, were no

DANCE REVIEW Intimacy’s Many Facets John Jasperse’s ‘Fort Blossom’ at New York Live Arts Andrea Mohin/The New York Times "Fort Blossom revisited (2000/12)": featuring, from left, Erika Hand, Lindsay Clark, Ben Asriel and Burr Johnson at New Yor