Transcription

AtrialFibrillationSection EditorsDeborah Cotton, MD, MPHDarren Taichman, MDSankey Williams, MDPhysician WriterPeter Zimetbaum, MDDiagnosispage ITC6-2Treatmentpage ITC6-6Practice Improvementpage ITC6-14Tool Kitpage ITC6-14Patient Informationpage ITC6-15CME Questionspage ITC6-16The content of In the Clinic is drawn from the clinical information andeducation resources of the American College of Physicians (ACP), including PIER(Physicians’ Information and Education Resource) and MKSAP (Medical Knowledgeand Self-Assessment Program). Annals of Internal Medicine editors develop In theClinic from these primary sources in collaboration with the ACP’s Medical Educationand Publishing Division and with the assistance of science writers and physician writers. Editorial consultants from PIER and MKSAP provide expert review of the content.Readers who are interested in these primary resources for more detail can consulthttp://pier.acponline.org, http://www.acponline.org/products services/mksap/15/?pr31,and other resources referenced in each issue of In the Clinic.CME Objective: To review current evidence for the diagnosis and treatment of atrialfibrillation.The information contained herein should never be used as a substitute for clinicaljudgment. 2010 American College of PhysiciansIn theClinicIn the Clinic

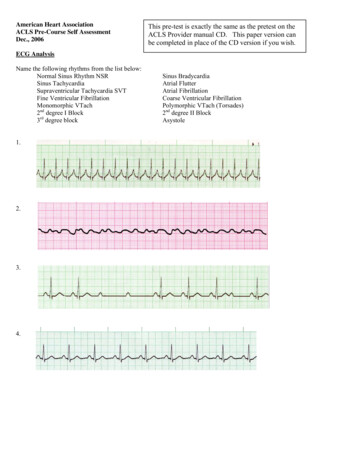

trial fibrillation (AF) is the most common, clinically significant cardiac arrhythmia. It occurs when a diffuse and chaotic pattern of electrical activity in the atria suppresses or replaces the normal sinusmechanism, leading to deterioration of mechanical function. Atrial fibrillation is a major cause of morbidity, mortality, and health care expenditures;prevalence in the United States is 2.3 million cases and is estimated to increase to 5.6 million by the year 2050 (1). Atrial fibrillation is associatedwith a 5-fold increased risk for stroke and is estimated to cause 15% of allstrokes (2). Independent of coexisting diseases, the presence of AF confers a2-fold increased risk for all-cause mortality (3).ADiagnosisWho is at risk for atrialfibrillation?Atrial fibrillation occurs in lessthan 1% of individuals aged 60 to65 years, but in 8% to 10% of thoseolder than 80 years. Prevalence ishigher in men than in women andhigher in whites than in blacks (1).The risk for AF increases with thepresence and severity of underlyingheart failure and valvular disease.1. Kannel WB, BenjaminEJ. Current perceptions of the epidemiology of atrial fibrillation. Cardiol Clin.2009; 27: 13-24.[PMID: 19111760]2. Hart RG, Benavente O,McBride R, Pearce LA.Antithrombotic therapy to prevent strokein patients with atrialfibrillation: a metaanalysis. Ann InternMed. 1999;131:492501. [PMID:10507957] 2010 American College of PhysiciansWhat symptoms and signs shouldcause clinicians to suspect atrialfibrillation?Some patients have prominentsymptoms, including palpitations,shortness of breath, exercise intolerance, chest pain, and malaise.However, many patients, particularly the elderly, have asymptomatic(silent) AF, including some patientswho have severe symptoms duringother AF episodes (4). Symptomsare generally greatest at disease onset—when episodes are typicallyparoxysmal—and tend to diminishover time, especially when thearrhythmia becomes persistent.Symptoms result from elevationof ventricular rate (either at rest orexaggerated by exercise), irregularventricular rate, and loss of atrialcontribution to cardiac output.On physical examination, signs ofAF include a faster-than-expectedheart rate, which varies greatlyfrom patient to patient, an “irregularly irregular” time between heartsounds on auscultation, and peripheral pulses that vary irregularly inboth rate and amplitude.ITC6-2In the ClinicIs a single electrocardiogramsufficient to diagnose or excludeatrial fibrillation?Figure 1 is an electrocardiogram(ECG) showing AF, and it indicates that a single ECG is sufficientto diagnose AF provided it isrecorded during the arrhythmia.However, AF is often paroxysmal,so a single ECG showing normalrhythm does not exclude the diagnosis. Monitoring for a longer timecan be helpful when AF is suspected and the initial ECG is normal.In patients with daily symptoms,24- or 48-hour continuous Holtermonitoring is usually sufficient tomake the diagnosis. In patients withless-frequent symptoms, monitoringduring longer periods with electrocardiographic loop recorders may benecessary. However, even monitoring for periods as long as a monthcan be nondiagnostic in patientswith very infrequent episodes. Inaddition, because patients must turnloop recorders on after symptomsbegin, these recorders are not helpful in detecting asymptomatic arrhythmias or arrhythmia-associatednonspecific symptoms that the patient may not recognize as being related to AF. It may take years toconfirm the diagnosis of AF insome patients because they havenonspecific symptoms and long periods between episodes.Some newer devices avoid theseproblems. New types of event monitors detect irregular ventricularrhythms and automatically startrecording regardless of symptoms.Annals of Internal Medicine7 December 2010

Figure 1. Electrocardiogram showing atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular rate.In addition, implanted pacemakersand implantable defibrillator–cardioverters with atrial leads identify and record both symptomaticand asymptomatic AF. Other newdevices continuously record heartrhythms for as long as a month andwirelessly transmit data to a centralmonitoring station, where automated systems interpret cardiacrhythms and report diagnoses inreal time (4a).What is the role of history andphysical examination in patientswith atrial fibrillation?History and physical examinationhelp determine the duration ofsymptoms and identify potentialunderlying causes. Cliniciansshould seek historical and physicalevidence of hypertension, heartfailure, cardiac surgery, murmursindicative of stenotic or regurgitantvalvular disease, and other indications of structural heart disease. Inaddition, clinicians should look forsigns and symptoms of noncardiaccauses of AF, including pulmonarydisease, hyperthyroidism, use ofadrenergic drugs (such as thoseused to treat pulmonary disease) orother stimulants, and use of alcohol. A family history might identifyfirst-degree relatives with AF,7 December 2010Annals of Internal Medicinewhich may someday have therapeutic implications.What other electrocardiographicarrhythmias can be confused withatrial fibrillation?Other arrhythmias that are commonly confused with AF include sinus rhythm with frequent prematureatrial contractions, atrial flutter, andatrial tachycardia. The key electrocardiographic findings of AF are theabsence of P waves and the presenceof an irregular ventricular rhythmwithout a recurring pattern. Whenan irregular rhythm is present butthe diagnosis of AF is uncertain, clinicians should examine long recordings from multiple leads looking forpartially obscured P waves in deformed T waves and ST segments.Figure 2 is an ECG of an irregularrhythm that might be attributed toAF, but the presence of P wavesand other features identify sinusrhythm with frequent prematureatrial contractions. Figure 3 is anECG of another irregular rhythmthat might be attributed to AF, butthe presence of “saw-tooth” P wavesand a ventricular response thatvaries from 2:1 atrioventricularconduction to 4:1 atrioventricularconduction identifies atrial flutter.3. Benjamin EJ, Wolf PA,D’Agostino RB, et al.Impact of atrial fibrillation on the risk ofdeath: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 1998;98:94652. [PMID: 9737513]4. Page RL, WilkinsonWE, Clair WK, et al.Asymptomatic arrhythmias in patientswith symptomaticparoxysmal atrial fibrillation and paroxysmal supraventriculartachycardia. Circulation. 1994;89:224-7.[PMID: 8281651]4a. Zimetbaum P, Goldman A. Ambulatoryarrhythmia monitoring: choosing theright device. Circulation. 2010;122:1629-36ITC6-3 2010 American College of PhysiciansIn the Clinic

Figure 2. Electrocardiogram showing sinus rhythm with frequent premature atrial contractions.5. American College ofCardiology/AmericanHeart AssociationTask Force on Practice Guidelines.ACC/AHA/ESC 2006Guidelines for theManagement of Patients with Atrial Fibrillation: a report ofthe American Collegeof Cardiology/American Heart AssociationTask Force on Practice Guidelines andthe European Societyof Cardiology Committee for PracticeGuidelines (WritingCommittee to Revisethe 2001 Guidelinesfor the Managementof Patients With AtrialFibrillation): developed in collaborationwith the EuropeanHeart Rhythm Association and the HeartRhythm Society. Circulation.2006;114:e257-354.[PMID: 16908781]Figure 3. Atrial flutter. Classic “saw-tooth” flutter waves are seen in all 12 leads, and the ventricularresponse is mostly regular. (There is a transient change from 2:1 to 4:1 atrioventricular conduction following the 12th QRS complex.) 2010 American College of PhysiciansHow should clinicians classifyatrial fibrillation?Although knowledgeable observersdisagree on the answer to this question, the most accepted conventioncategorizes AF as paroxysmal, persistent, or permanent (5) (Box 1).“Paroxysmal” AF means that episodesterminate without intervention infewer than 7 days (often within 24hours). “Persistent” AF means thatepisodes last longer than 7 days or require an intervention, such as cardioversion, to restore sinus rhythm.“Permanent” AF means that the arrhythmia is continuous, and interventions to restore sinus rhythm have either failed or not been attempted.The same patient may be classifiedinto different categories at differenttimes, so clinicians should classify patients according to the current patternor most common pattern.ITC6-4Annals of Internal MedicineIn the ClinicThese distinctions are usefulbecause they predict responsesto therapy. For example, patientsare less likely to respond to7 December 2010

antiarrhythmic drug therapy as thepattern goes from paroxysmal topersistent to permanent. Patients inall 3 categories, however, requireanticoagulation.What laboratory studies shouldclinicians obtain in patients newlydiagnosed with atrial fibrillation?When patients initially present withAF, clinicians should measure serumelectrolytes and thyroid-stimulatinghormone to identify possible causes.They should measure blood tests forrenal and hepatic function to guidethe selection of drug therapy andcheck a stool Hemoccult test beforestarting anticoagulation. Transthoracic echocardiography helps determine the patient’s potential responsiveness to antiarrhythmic therapy bymeasuring left atrial size and assessing for valvular heart disease, pericardial disease, and left ventricularhypertrophy. A transesophagealechocardiogram to exclude atrial clotis indicated when transthoracic images are inadequate or cardioversionis planned in a patient who has beentherapeutically anticoagulated forless than 3 weeks. In patients withappropriate clinical indications, additional tests may be appropriate toevaluate the patient for pulmonaryembolism, acute myocardial infarction, or acute heart failure.What underlying conditionsshould clinicians look for inpatients with atrial fibrillation?Eighty percent of patients with AFhave structural heart disease, particularly hypertensive heart diseasebut also coronary artery disease,valvular heart disease, or cardiomyopathy. Atrial fibrosis occurs frequently with structural heart disease, and many people consideratrial fibrosis central to the arrhythmia’s pathogenesis. “Lone” AFrefers to AF in the absence of heartdisease. Some experts believe thatthe diagnosis of lone AF should berestricted to patients younger than60 years of age because it is difficult to exclude structural heartdisease in older patients (6).Some acute illnesses are associatedwith AF, including acute myocardialinfarction, pulmonary embolism, andthyrotoxicosis. Atrial fibrillation occurs in approximately 40% of patients after cardiac or thoracic surgery, but it may also occur after othertypes of major surgery or during asevere illness. Obesity and sleep apnea are associated with an increasedincidence of AF.Atrial fibrillation also occurs inpeople who have no predisposingconditions. These patients are typically men 40 to 50 years of age, andsymptoms often occur at night, atrest, following vigorous exercise, orwith alcohol use. The mechanismsare unclear but may involve increases in circulating catecholamines, changes in myocardialconduction times and refractoryperiods, and increases in vagal tone.Other forms of AF without knownunderlying conditions occur duringwaking hours and are preceded byemotional stress or exercise.Diagnosis. Atrial fibrillation is the most common clinically significant cardiacarrhythmia, and its prevalence increases with advancing age. Typical symptomsinclude palpitations, shortness of breath, and exercise intolerance. However, somepatients report only general malaise, and many patients are asymptomatic. Electrocardiogram recordings during episodes are the only way to confirm the diagnosis. If the diagnosis is suspected and the ECG is normal, longer monitoring witha loop recorder or a Holter monitor can be helpful. The initial assessment shouldinclude laboratory tests for electrolytes, thyroid-stimulating hormone, and renaland hepatic function to rule out underlying disorders or contraindications totherapies. An echocardiogram should be done to look for structural heart disease.CLINICAL BOTTOM LINE7 December 2010Annals of Internal MedicineIn the ClinicITC6-5Classification of Atrial FibrillationParoxysmal: Episodes spontaneouslyterminate within 7 daysPersistent: Episodes last 7 days andrequire intervention to restore sinusrhythmPermanent: Interventions to restore sinusrhythm have either failed or have notbeen attempted6. Furberg CD, Psaty BM,Manolio TA, et al.Prevalence of atrialfibrillation in elderlysubjects (the Cardiovascular HealthStudy). Am J Cardiol.1994;74:236-41.[PMID: 8037127]7. Naito M, David D,Michelson EL, et al.The hemodynamicconsequences of cardiac arrhythmias:evaluation of the relative roles of abnormal atrioventricularsequencing, irregularity of ventricularrhythm and atrial fibrillation in a caninemodel. Am Heart J.1983;106:284-91.[PMID: 6869209]8. Risk factors for strokeand efficacy of antithrombotic therapyin atrial fibrillation.Analysis of pooleddata from five randomized controlledtrials. Arch InternMed. 1994;154:144957. [PMID: 8018000]9. Brand FN, Abbott RD,Kannel WB, Wolf PA.Characteristics andprognosis of loneatrial fibrillation. 30year follow-up of theFramingham Study.JAMA. 1985:254:344953. [PMID: 4068186]10. Hart RG, ShermanDG, Easton JD,Cairns JA. Preventionof stroke in patientswith nonvalvularatrial fibrillation.Neurology.1998;51:674-81.[PMID: 9748009] 2010 American College of Physicians

TreatmentSituations in Which Patientswith Atrial Fibrillation MayRequire Hospitalization Uncertain or unstable underlying arrhythmia Acute myocardial infarction, altered mental status, decompensated heart failure, or hypotension Intolerable symptoms despitehemodynamic stability Elective cardioversion (if monitored outpatient setting is notavailable) Acute anticoagulation if veryhigh risk for stroke Telemetry monitoring duringinitiation of certain drugs Procedures such as cardiaccatheterization, electrophysiologic studies, pacemakers, implantable defibrillators, orcatheter or surgical ablation11. Redfield MM, KayGN, Jenkins LS, et al.Tachycardia-relatedcardiomyopathy: acommon cause ofventricular dysfunction in patients withatrial fibrillation referred for atrioventricular ablation.Mayo Clin Proc.2000;75:790-5.[PMID: 10943231]12. Chung MK. Schweikert RA. Wilkoff BL, etal. Is hospital admission for initiation ofantiarrhythmic therapy with sotalol foratrial arrhythmias required? Yield of inhospital monitoringand prediction ofrisk for significant arrhythmia complications. JACC.1998;32:169-76.[PMID: 9669266]13. Atrial Fibrillation Follow-up Investigationof Rhythm Management (AFFIRM) Investigators. A comparison of ratecontrol and rhythmcontrol in patientswith atrial fibrillation.N Engl J Med.2002;347:1825-33.[PMID: 12466506]14. Hohnloser SH, KuckKH, Lilienthal J.Rhythm or rate control in atrial fibrillation—Pharmacological Intervention inAtrial Fibrillation(PIAF): a randomisedtrial. Lancet.2000;356:1789-94.[PMID: 11117910] 2010 American College of PhysiciansWhat are the complications ofatrial fibrillation, and how cantherapy decrease the risk forthese events?There are 3 reasons to treat AF: toreduce symptoms, to preventthromboembolism, and to preventcardiomyopathy.Although AF is not always symptomatic, the symptoms can be disabling. Symptoms are usuallycaused by inappropriately rapidventricular rates or the irregularityof the ventricular response (7). Theloss of atrial contribution to ventricular filling (“atrial kick”) is welltolerated by most patients exceptthose with ventricular hypertrophyfrom long-standing hypertension,aortic stenosis, and hypertrophicobstructive cardiomyopathy.infarction, hypotension, or highrisk for acute stroke. Patients withAF and the Wolff-ParkinsonWhite syndrome can have extremely rapid atrioventricular conduction mediated by the accessorypathway, which can be a potentially life-threatening conditionand require urgent cardioversion.Which patients with atrialfibrillation should cliniciansconsider hospitalizing?Although AF is usually managed inan outpatient setting, cliniciansshould consider hospitalizing patients with AF when managementrequires close monitoring for safety(12) (Box 2).It is important to treat the tachycardiaof AF because it can lead tocardiomyopathy if left untreated (11).Should clinicians attempt ratecontrol or rhythm control?Traditionally, most clinicians havepreferred rhythm control to ratecontrol, but recent, high-qualityclinical trials have shown thatrhythm control generally does notimprove mortality, stroke, hospitalization, or quality of life comparedwith rate control (13, 14). Ratecontrol is easier to accomplish andprevents exposure to the potentialadverse effects of antiarrhythmicagents. On the other hand, rhythmcontrol may be useful in selectedpatients with severe symptoms (before or after failure of rate control)or in younger patients withoutstructural heart disease.When should clinicians considerimmediate cardioversion inpatients with atrial fibrillation?Prompt cardioversion should beconsidered for new-onset AFwhen the duration of the arrhythmia is less than 48 hours. One example is a hospitalized patient oncardiac monitoring. Most patientswith AF do not require immediatecardioversion, but it can obviatethe need for anticoagulation andmay be appropriate in selected patients with decompensated heartfailure, severe angina or acuteThe AFFIRM (Atrial Fibrillation Follow-upInvestigation of Rhythm Management) trial included 4060 patients with AF who hadat least 1 risk factor for stroke. The meanage was 69 years, and structural heart disease, aside from hypertension, was unusual. All-cause mortality at 5 years was 25.9%in the rate-control group and 26.7% in therhythm-control group (P 0.080). Patientswith apparently successful rhythm controlstill needed anticoagulation because ofpersistent stroke risk, and patients whowere able to maintain sinus rhythm had asurvival advantage that was almost balanced by the disadvantage imposed byantiarrhythmic drug therapy (15).ITC6-6Annals of Internal MedicineStroke is the most common formof arterial thromboembolism during AF. In patients with nonvalvular AF, the average annual risk forarterial thromboembolism, including stroke, is 5%, and the risk ishigher in patients older than age 75years (8). The risk is related to specific features of AF as well as otherrisk factors for thromboembolism(9). Left atrial thrombi cause 75%of strokes in patients with AF (10).In the Clinic7 December 2010

A more recent trial extended these observations to patients with severe heart failure by randomly assigning 1376 patientswith AF, left ventricular ejection fractionof 35%, and heart failure symptoms torate control versus rhythm control. At 37months, death from cardiovascular disease occurred in 25% of the rate-controlgroup and in 27% of the rhythm-controlgroup (P 0.6). There was no improvement in all-cause mortality, stroke, heartfailure, or need for hospitalization in therhythm-control group (16).What strategies should cliniciansconsider for rate control inpatients with rapid atrialfibrillation?Clinicians should consider drugtherapy to control ventricular rate inall patients with AF, even if rhythmcontrol is eventually done. Althoughcriteria for rate control vary with patient age, the traditional target hasbeen heart rates of 60 to 80 beats perminute at rest and between 90 to115 beats per minute during moderate exercise (17). However, a recentstudy comparing a strategy of lenientrate-control (resting heart rate 110beats per minute) with a strategy ofstrict rate control ( 80 beats perminute), found no advantage to thestricter rate control strategy (18).Recommended first-line therapy todecrease atrioventricular nodal conduction includes β-blockers andnondihydropyridine calcium-channelantagonists (Table 1). A recently approved antiarrhythmic medication,dronedarone, has also been shown tobe safe and modestly effective forrate control of AF (19).Digitalis and amiodarone block theatrioventricular node but are not recommended as first-line monotherapyfor rate control (17). Digitalis doesnot reduce the tachycardia that occurs with exercise, and it is unlikelyto control rate in patients with heartfailure and high sympathetic activity.Amiodarone is occasionally used toreduce ventricular response if otheragents have failed, but this practice isdifficult to justify because of the associated toxicities (20).7 December 2010Annals of Internal MedicineWhat strategies should cliniciansconsider for rhythm control inpatients with atrial fibrillation?Rhythm control is no longer thepreferred strategy in most patientswith AF. The trials comparingrate control with rhythm control,however, have not includedyounger patients or those withhighly symptomatic AF. Therefore, it is reasonable to considerrhythm control in these patients.Also, experienced clinicians oftenprefer rhythm control for the firstepisode of symptomatic AF inyounger patients because manymaintain sinus rhythm withoutantiarrhythmic drug treatment after cardioversion.Patients can be converted to normal sinus rhythm with direct electrical current or with drugs. Electrical cardioversion is indicatedwhen the patient is hemodynamically unstable. When the patient ishemodynamically stable, the conversion rate with antiarrhythmicdrugs is lower than that with electrical direct current but does notrequire deep sedation or generalanesthesia and may facilitate thechoice of antiarrhythmic drug therapy to prevent recurrence.Patients should receive therapy toachieve both rate control and adequate anticoagulation before electivedirect current or pharmacologic cardioversion of AF more than 48hours in duration. In addition, theserum potassium level should begreater than 4.0 mmol/L, serummagnesium level should be greaterthan 1.0 mmol/L, and ionized calcium levels should be greater than 0.5mmol/L. In most cases, cardioversion should be performed in a monitored hospital setting to permit adequate assessment of the degree ofrate control, bradycardia, proarrhythmic affects of antiarrhythmic agents,and other adverse effects (21).Antiarrhythmic drugs other thanamiodarone generally have equalIn the ClinicITC6-715. AFFIRM Investigators. Relationshipsbetween sinusrhythm, treatment,and survival in theAtrial Fibrillation Follow-Up Investigationof Rhythm Management (AFFIRM)Study. Circulation.2004;109:1509-13.[PMID: 15007003]16. Atrial Fibrillation andCongestive HeartFailure Investigators.Rhythm control versus rate control foratrial fibrillation andheart failure. N EnglJ Med.2008;358:2667-77.[PMID: 18565859]17. American College ofCardiology/American Heart Association Task Force onPractice Guidelines.ACC/AHA/ESC 2006Guidelines for theManagement of Patients with Atrial Fibrillation. Circulation.2006;114:e257-354.[PMID: 16908781]18. Van Gelder IC,Groenveld HF, CrijnsHJGM, et al. Lenientversus Strict ratecontrol in patientswith atrial fibrillation.N Engl J Med.2009;12;360:668-78.[PMID: 20231232]19. Davy JM, Herold M,Hoglund C, et al.Dronedarone for thecontrol of ventricularrate in permanentatrial fibrillation: theEfficacy and safety ofdRonedArone forthe cOntrol of ventricular rate duringatrial fibrillation (ERATO) study. AmHeart J.2008;156:527.e1-9.[PMID:18760136]20. Vassallo P. TrohmanRG. Prescribingamiodarone: an evidence-based reviewof clinical indications. JAMA.2007;298:1312-22.[PMID: 17878423]21. Maisel WH, KuntzKM, Reimold SC, etal. Risk of initiatingantiarrhythmic drugtherapy for atrial fibrillation in patientsadmitted to a university hospital. AnnIntern Med.1997;127:281-4.[PMID: 9265427] 2010 American College of Physicians

Table 1. Drug Therapy for Rate and Rhythm Control in Atrial FibrillationAgentMechanism of ActionRate-Controlling Agentsß-BlockersMetoprolol Selective ß1-adrenergic–receptor blocking agentDosageBenefitsConvenient IVadministration in NPOpatients, rapid onset ofaction, dependable AVnodal blockadePropranolol Nonselective ß-adrenergic– 1–8 mg IV (1 mg every Inexpensive, commonlyreceptor blocking agent2 min). 10–120 mg PO available3 times daily; longacting preparation:80–320 mg PO oncedaily.EsmololShort-acting IV ß10.05–0.2 mg/kg perShort-acting, titratableselective adrenergicmin IVon or off with very rapidreceptor-blocking agenthalf-lifePindololNonselective ß-adrenergic– 2.5–20 mg PO 2–3Less bradycardia, lessreceptor blocking agenttimes dailybronchospasmwith intrinsic sympathomimetic activityAtenololSelective ß1-adrenergic–5 mg IV over 5 min,Does not cross blood–receptor blocking agentrepeat in 10 min.brain barrier, fewer25–100 mg PO onceCNS side effectsdailyNadololNonselective ß-adrenergic– 20–120 mg once daily Lower incidence ofreceptor blocking agentcrossing blood–brainbarrier, fewer CNS sideeffectsCalcium-channel blockersVerapamilCalcium-channel blocking 5–20 mg in 5-mgConsistent AV nodalagentincrements IV everyblockade30 min, or 0.005 mg/kgper min infusion.120–360 mg PO daily,in divided doses or inthe slow-release form.DiltiazemCalcium-channel blocking 0.25–0.35 mg/kg IVConsistent AV nodalagentfollowed by 5–15 mg/h. blockade120–360 mg PO dailyas slow releaseCardiac glycosideDigoxinNa /K pump inhibitor,0.75–1.5 mg PO or IV Particularly useful forincreases intracellularin 3–4 divided dosesrate control in CHFcalciumover 12–24 h.Maintenance dose:0.125 mg PO or IV to0.5 mg dailyAntiarrhythmic agentsClass IaProcainamide Prolongs conductionand slows repolarizationby blocking inward Na fluxQuinidinegluconateProlongs conduction andslows repolarization.Blocks fast inward Na channel5 mg IV every 5 min,up to 15 mg 50–100mg PO twice dailySide EffectsNotesBradycardia, hypotension,heart block,bronchospasm (lessfrequently than nonselectiveß-blockers), worsening of CHFBradycardia, hypotension,heart block, bronchospasm,worsening of CHFBradycardia, hypotension,heart block, bronchospasm(less frequent)Bradycardia, hypotension,heart blockOccasionallyinconsistent effect inhigh-catecholamine statesLess propensity forheart block thanother ß-blockersBradycardia, hypotension,heart blockBradycardia, hypotension,heart blockOral form onlyHypotension, heart block,direct myocardial depressionDo not use in theWolff–Parkinson–White syndromeHypotension, heart block, lessmyocardial depressionDo not use in theWolff–Parkinson–White syndromeHeart block, digoxinassociated arrhythmias;dosage adjustment requiredin renal impairmentFirst-line therapyonly in patients withdecreased leftventricular systolicfunction. Not usefulfor rate control with exercise. Not useful for conversion of AF or aflutter toNSR.1–2 g q 12 h (shorter- Convenient IV dosingacting oral preparations available withare no longer available) maintenance infusion,and conversion to POtablets, very effectiveat converting AF toNSRNot recommended becauseof frequent side effects,including hypotension,nausea, vomiting,lupus-like syndrome, QTprolongation, andarrhythmiaNeed to follow druglevels and QT intervalfor toxicity, adjustdose in patients withrenal insufficiency.Not for use in patientswith severe LVdysfunction.324–648 mg POevery 8–12 hProarrhythmia, nausea,vomiting, diarrhea,QT prolongationNot recommendedbecause of frequentside effects. Followdrug levels and QT interval for toxicity. Adjust dosein patients with renal insufficiency. Oral agent only.Relatively effective inconverting AF to NSRbut may take severaldays to achieve NSRbecause of PO dosing(continued on next page) 2010 American College of PhysiciansITC6-8In the ClinicAnnals of Internal Medicine7 December 2010

Table 1 (continued). Drug Therapy for Rate and Rhythm Control in Atrial FibrillationAgentMechanism of ActionDosageBenefitsAntiarrhythmic agentsClass IaDisopyramide Similar electrophysiologic 150 mg PO everyCan be useful inproperties to procainamide 6–8 h, or 150–300 mg patients withand quinidinetwice a dayhypertension andnormal LV functionClass IcFlecainideBlocks Na channels2 mg/kg, IV. 50–150Efficacy in paroxysmal(and fast Na current)mg PO every 12 h.AF with structurallyAlso, single loadingnormal heartsdoses of 300 mg areefficacious in conversionof recent onset AF.Propafenone Blocks myocardial2 mg/kg, IV. 150–300 Efficacy in paroxysmalNa channelsmg PO every 8 h. Also, and sustained AFsingle loading doses of600 mg are efficaciousin conversion of recentonset AF.Class IIIIbutilideProlongs action potential 1 mg IV over 10 min.Efficacy in acute andduration (and atrial andMay be repeated once rapid conversion of AFventricular refractoriness) if necessary.to NSRby blocking rapidcomponent of delayedrectifier potassium current5–7 mg/kg IV up to1500 mg per 24 h.400–800 mg PO daily,for 3–4 wk, followedby

Editorial consultants from PIER and MKSAP provide expert review of the content. Readers who are interested in these primary resources for more detail can consult . To review current evidence for the diagnosis and treatment of atrial fibrillation. The information contained herein shoul