Transcription

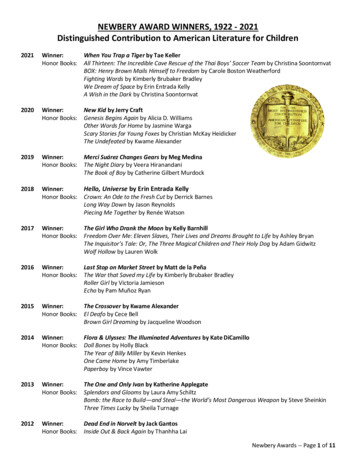

Journal of Language and Literacy Education Vol. 16 Issue 2—Fall 2020Diversity in Newbery Medal-Winning Titles: A Content AnalysisMelanie D. Koss & Kathleen A. PacigaAbstract: This paper shares results from a critical content analysis of Newbery-winning titles from 1922-2019for representations of race/ethnicity, gender, and disability. Each title was coded for the inclusion and&representation of race/ethnicity, gender, and disability at both the book and main character levels. Lenses ofcritical race, gender schema, and critical disability theories were used to classify the ways race/ethnicity,gender, and ability of diverse populations are portrayed and represented in Newbery-winning titles. Resultswere then compared to U.S. Census and National Center for Education Statistics data about today’s publicschool population. Representations of diversity in Newbery-winning titles are not confluent with therace/ethnicity, gender, and disability of children in U.S. schools. Given the prominence of Newbery-winningliterature in elementary schools, children are likely to come across these unrepresentative characters.Keywords: children's & young adult literature; disability; diversity; reading & literature instructionMelanie D. Koss is associate professor of literacy education in the Department of Curriculum andInstruction at Northern Illinois University. Her research interests include examining representations ofdiversity in children’s and young adult literature, ways culturally relevant pedagogy can be used to inspirediverse forms of reader response, and the role of literature in the teaching of English language learners.Contact the author at mkoss@niu.edu.Kathleen A. Paciga is associate professor of education at Columbia College Chicago. Katie’s researchfocuses on the ways in which media, in all its forms, contribute to teaching and learning in the earlychildhood and elementary school years. She studies the socio-cultural significance of media in childhood,attending to the social, emotional, cultural, and cognitive bases for language and literacy development.Contact the author at kpaciga@colum.edu.1

Journal of Language and Literacy Education Vol. 16 Issue 2—Fall ssaresignificantly impacted by the books they read andinteract with (Chaudhri & Teale, 2013), and readingand discussing a variety of books assists children in(1) developing a positive sense of self (Levin, 2007)and (2) critically examining their world andperspectives (Braden & Rodriguez, 2016; Thein et al.,2007).iverse, positive role models for race,ethnicity, gender, and disability exist in bothfiction and nonfiction characters, and arefeatured in the public media. These rolemodels are powerful figures as they inspire andmotivate today’s children, allowing them to see thepossibilities of success for all people. The authenticcharacterization of African T’Challa by ChadwickExamining a set of highly-regarded and well-knownBoseman in Marvel’s Black Panther and theaward-winning texts, such as Newbery winners,entrepreneurial spirit of Marley Dias have beenprovides insight into books that have a strongcaptured in children’s books and blockbuster filmspossibility of getting into the hands of children. This(e.g., Black Panther: The Battle for Wakanda, Snider,study employs content analysis to describe the2018; Marley Dias Gets It Donehuman characters in the corpusand So Can You, Dias, 2018;of Newbery Medal-winning texts“Diverse characters andWarriors of Wakanda, Berrios,1922-2019, examining depictionspeople assist children as2018). Malala Yousafzai madeof diversity in terms oftheyinternalizeandlearnheadlines in her fight for therace/ethnicity,gender,andrights of girls and women innorms and values about the ableness.Pakistan (I am Malala: How Oneworld in which they liveWhy Children Need to SeeGirl Stood Up for Education andthroughovertorcovertThemselves in BooksChanged the World, Yousafzai &Dmessages.”McCormick, 2016; Malala: MyDiverse literature gives childrenStory of Standing Up for Girls’insight into their own culture andRights, Robbins & Yousafzai, 2018). Auggie, a boysurroundings as well as insight into the cultures ofwith a facial deformity who proved himself as beingothers, potentially giving rise to discussions ofjust as human and everyone else, won the hearts ofdiversity (Colby & Lyon, 2004). A well-knownaudiences everywhere and championed the “Choosemetaphor by Bishop (1990a) thinks of literature asKind” movement with Wonder, (Palacio, 2012).mirrors, windows, and sliding glass doors throughwhich children can see themselves and others.Diverse characters and people assist children as theyMirrors allow children to see reflections ofinternalize and learn norms and values about thethemselves, windows provide a view into the worldsworld in which they live through overt or covertof others, and sliding glass doors allow a reader tomessages. They function “as a major socializingtraverse into the world of others. Sciurba (2014/2015)agent. [They tell] students who and what their societybuilt upon this metaphor by bringing in anand culture values, what kind of behaviors areindividual’s identity, positing that individuals areacceptable and appropriate, and what it means to bemultilayered, and that differing levels of empathy anda decent human being” (Bishop, 1990b, p. 561).1We acknowledge that there is a gender spectrum andthat myriad pronouns exist that we can use whenreferring to individuals in our writing. Throughout thisarticle we use pronouns to refer to individuals thatcorrespond with the pronouns used in the literatureanalyzed.2

Journal of Language and Literacy Education Vol. 16 Issue 2—Fall 2020awareness impact a child's connection to a text. It ismore than just seeing oneself in a text, but alsoconnecting to a character or event through acommon experience or sympathizing with acharacter different from oneself. Young et al. (2019)expanded on this idea by stating that literature thatdepicts equality in various cultures affects children’sview of their worlds.confirming a continued lack of diversity in children’sbooks.In 2015, the National Council of Teachers of English(NCTE) released the position statement “Resolutionon the Need for Diverse Children’s and Young AdultBooks,” acknowledging that today’s children’s booksdo not align with the increasing diversity in theUnited States. Proof can be found in the CooperativeChildren’s Book Center’s (CCBC) annual statisticsabout children’s books published by and/or aboutpeople of color. Due to the fact that “Whitecharacters are not—and never have been—lacking inbooks for humans and teens,” the CCBC does notdistinguish White human characters from otheranthropomorphizedanimalcharactersandinanimate objects (CCBC, 2020b). Their most recentdata show that across 4,029 books published in theU.S. in 2019, that include both human and ically diverse themes, topics, and/orhuman main or principal secondary characters(CCBC, 2020a). Recently, renewed attention has beenpaid to this lack of diversity in the publishing world.As a response to an all-White, all-male panel ofchildren’s book authors at the 2014 BookConconvention, the hashtag #WeNeedDiverseBookstrended, leading to the non-profit organization WeNeed Diverse Books (WNDB). WNDB advocates for“essential changes in the publishing industry toproduce and promote literature that reflects andhonors the lives of all young people” (WNDB, 2020).Children’s books are powerful tools for helpingchildren understand discrimination at an early age(Banks, 2019), including discrimination on the basisof gender, religion, and disability. Hidden messagesin books, specifically about power dynamics andwho/what is valued in a society, whether intentionalor not, also play a role in a child’s identitydevelopment, as these messages can be internalizedand affect a child’s sense of self (Botelho & Rudman,2009; Lakoff & Johnson, 1980). The stories that adultsshare with children can affect their conceptualizationof who they are and where they fit into their world(e.g. Al-Hazza & Bucher, 2008; Landt, 2011).Children’s literature “allow[s] all students tounderstand their uniqueness, to understand thecomplexities of ethnicity and culture, and to takepride in who they are as people as well as learn torespect other cultural groups” (Banks, 1989, p. 6).The Current State of Children’s PublishingSince Larrick’s (1965) study The All-White World ofChildren’s Books—that addressed the considerablelack of representation of characters of color,specifically African American characters, and thestereotypical portrayals of those included—thedearth of diversity in children’s books has garneredmuch attention. Scholars have analyzed andproblematized the lack of diverse representation inchildren’s books (e.g., Bishop, 1982; Harris, 1997;Rollins, 1967) looking specifically at ethnicity (e.g.,Naidoo, 2008), gender (e.g., Houdyshell & Martin,2010), and disability (e.g., Leininger et al., 2010)—allIn 2019, the American Library Association (ALA)included three well-established awards into theirYouth Media Awards (YMA) ceremony. Now, inaddition to the Coretta Scott King Award for booksby and about African Americans, the Pura BelpréAward for Latinx authors and illustrators, and theSchneider Family Book Award for representations ofthe disability experience, the YMA ceremony alsoannounces the Asian/Pacific American Award for3

Journal of Language and Literacy Education Vol. 16 Issue 2—Fall 2020Literature designed to “honor and recognizeindividual work about Asian/Pacific Americans andtheir heritage”; the Sydney Taylor Book Award to“recognize books that authentically portray theJewish experience”; and the American Indian YouthLiterature Award to “identify and honor the very bestwriting and illustrations by and about AmericanIndians” (Association for Library Services to Children[ALSC], 2019]). Announcing these awards at the YMAannouncements provides greater attention to awardsfor diverse populations and shows a dedication torecognizing the work of diverse authors andillustrators.“a contribution to American literature . . . [decided]primarily on the text . . . [although] [o]thercomponents of a book, such as illustrations, overalldesign of the book, etc., may be considered when theymake the book less effective”; and (3) “the book mustbe a self-contained entity” (ALSC, n.d.). Note that theaward is not based on popularity but rather onperceived literary merit, and although considerationsof representations of diversity are a naturalcomponent of book evaluation in terms of accuracyand authenticity, they are not determined to becriteria of the award.Teachers and librarians often rely on book awards toselect quality literature. As a result, award-winningbooks are often included in the curriculum and inschool and classroom libraries, thereby ensuringlikely access to and engagement with these texts(Kidd, 2007; Yokota, 2011).The Influence of Newbery Medal BooksThe John Newbery Medal is awarded annually by theALA to “the author of the most distinguishedcontribution to American literature for children”published in the preceding year (ALSC, n.d.). Thepurpose of the award is:The Newbery Medal’s Impact on the ConsumerMarketTo encourage original creative work in the field ofbooks for children. To emphasize to the publicthat contributions to the literature for childrendeserve similar recognition to poetry, plays, ornovels. To give those librarians, who make it theirlife work to serve children's reading interests, anopportunity to encourage good writing in thisfield. (ALSC, n.d., para. 3)Newbery Medal winners rarely go out of print,“ensuring a permanent place on a publisher’sbacklist” (Clark, 2003, p. 74). Since its inception, onlyone book is currently out of print, Daniel Boone byJames Daugherty (1939), due to extreme racism andperpetuation of stereotypes. These books are readilyavailable and frequently bought; “the distinction ofwinning the awards helps to keep books in print,insuring cumulative sales over a longer period”(Maughan, 2011, para. 2). According to Anita Silvey,“[n]o other award has the economic significance ofthe Newbery and Caldecott” (Maughan, 2011, para. 2)leading to an instant increase of book sales(Cockcroft, 2018).Since its inception, almost a century of titles havebeen awarded the medal along with yearly honorbooks, and these books have largely become a part ofthe children’s literature canon (Kidd, 2007).There are three main criteria for the Newbery award:(1a) literary quality as determined by “interpretationof the theme or concept; presentation of informationincluding accuracy, clarity, and organization;development of a plot; delineation of characters;delineation of a setting; appropriateness of style”; (1b)“excellence of presentation for a child audience”; (2)The Newbery Medal as a Purposive SampleScholars of children’s literature analyze NewberyMedal- and Honor-winning texts due to theirprevalence in curricula and classrooms. Previous4

Journal of Language and Literacy Education Vol. 16 Issue 2—Fall 2020content analyses have been done on subsets ofNewbery titles with targeted foci. These studiestended to focus on specific, defining constructs suchas race/ethnicity, gender, and disability. Additionally,many studies of constructs within the NewberyMedal are student studies, such as master’s thesesand dissertations, and such studies rarely reach anaudience outside their academic context.from 1922-1974, thereby covering much of the span ofNewbery winner and honor books. These studiesfound that many characters with disabilities wereportrayed positively across time, although there wasa significant lack of such characters represented.Limited foci in these studies allow for deeper analysis;they do not provide a large-scale understanding ofthe award across time and/or multiple constructs.What makes this study unique is that it examines theentirety of Newbery Medal-winning titles from theMedal’s inception to 2019 for representations ofrace/ethnicity, gender, and disability. (Henceforththe term Newbery-winning books refers only toMedal winners and not Honor books.)Studies that examined race/ethnicity have tended tolook at portrayal of non-White characters, oftenfocusing on their role in the book (e.g., Gillespie etal., 1994), on stereotypical portrayals (e.g., Wilkin,2009), or on rate of visibility (e.g., Clark, 2007; Miller,1998). General findings included that there is a lackof diverse characters, although the visibility haschanged during different time periods; and thatanalyses of portrayals have been based oncontemporary, cultural realities.Theoretical FrameworkThe present study provides an overview of the data,analysis, and findings from a larger project thatleveraged critical theories to frame the authors’analysis of the entire Newbery Medal-winningcorpus. In the larger project, Critical Race Theory(CRT), Gender Schema Theory (GST), and CriticalDisability Theory (CDT) are used to problematize theways in which diverse populations, includingrace/ethnicity, gender, and disability, are portrayedand represented in Newbery-winning titles. Theserepresentations are characters children are likely tosee in books, and consequently, characters that couldimpact their identity development. This articlepresents a broad view of the findings.The majority of studies analyzing a corpus ofNewbery-winning books has focused on examiningthe books for gender representation. Many haverelied on frequency counts, finding a predominanceof male main characters through the years of theaward. However, female main characters have eithergrown in number or shared the spotlight with malemain characters in ensemble casts (e.g. Clark, 2007;Powell et al., 1998). Studies have also examinedtraditional versus nontraditional gender roles (e.g.Groce, 2010; Houdyshell & Martin, 2010), finding thatportrayals of both male and female main charactershave increased in number of nontraditionaldepictions, although traditional roles still remainprevalent.Critical theories such as CRT, GST, and CDT positthat individuals learn their roles and values in societythrough unwritten social rules and social norms(McLeod, 2008) and that individuals are socialized tointernalize thoughts and behaviors of themselves andothers in their worlds. CRT problematizes waysracism is inherent and learned, GST problematizesways gender roles and norms are developed, and CDTproblematizes ways depictions of individuals withLeininger, Dyches, and Prater are known for researchon disability representation in children’s literature,and in 2010 published a study focused on Newberybooks from 1975-2009 (Leininger et al, 2010). Thisstudy was supplemented by a related thesis by one oftheir students examining disability portrayal in books5

Journal of Language and Literacy Education Vol. 16 Issue 2—Fall 2020disabilities influence perceptions of their place androle in society.1999). GST suggests that a child’s gender identity isaffected by the variety of gender roles and expressionsthey see in society and the materials they come intocontact with (Egan & Perry, 2001; Nielson et al., 2020).Butler (2004) expands upon this and calls for adisruption of the binary view of sex and gender,arguing that gender is a performative act that isreinforced by societal norms.CRT examines implicit and explicit bias in society andstates that racism must be acknowledged. Delgadoand Stefanic (2001) outline five tenets of CRT thatposit that (a) racism is common and prevalent insociety; (b) racism is difficult to address due to itsbeing embedded in daily life; (c) the concept of raceis a product of society and social thought; (d)racialization is different depending on the needs ofthe dominant society; and (e) counter-narratives arecritical to give people of a color a voice.Following the same foundational tenets, CDTexamines the ways disabilities and individuals withdisabilities are portrayed, focusing on the social andcultural perspectives rather than medical orrehabilitative ones (Saunders,2004) that work to problematize“When educators’,the beliefs and assumptions ofscholars’, and publishers’ableism present in society (Hunt,1966).interests privilege theAn additional component of CRTis interest convergence theory(Bell, 1992), which asserts thatequality among and betweenpeople, specifically Black people,publication and inclusioncan only be reached when theThese three theories haveofdiverseliterature,interests of BIPOC align with, orpreviously been used in researchthereby allowing allconverge with, those of Whiteon children’s literature, becausepeople. Inequitable education,when children read books, theychildren the opportunity toincluding access to racially andalso read culture. Thus, they aresee themselves and makeethnically diverse literature,socialized into learning the waysconnectionstothebooksensures White social advantagethey fit into their wider society,(Milner et al., 2013; Rectorsincebiasesdepictedinthey read, greater equalityAranda, 2016; Souto-Manning etchildren’s books can contributecan be attained.”al., 2019). When �,andpublishers’(Hamilton et al., 2006). Existinginterests privilege the publication and inclusion ofcontent analyses of literature, featured in subsequentdiverse literature, thereby allowing all children theparagraphs, have used these theories individually,opportunity to see themselves and make connectionsanalyzing a subset of books for depictions ofto the books they read, greater equality can berace/ethnicity, gender, or disability.attained.Studies using CRT have examined characterSimilar to CRT, GST is a cognitive theory thatdepictions and language in presenting characters ofproposes that children learn gender roles from theirdifferent races in order to point out assumptiveculture by both human interactions and interactionsportrayals (Brissett, 2019; Wiseman et al., 2019). Manywith different forms of media such as books,studies that use CRT focus on a specific population,television, movies, and games (Bem, 1983; Martin &such as depictions of African Americans (e.g., BrooksHalverson, 1981; Trepanier-Street & Romatowski,& McNair, 2015; Wilkin, 2009), Latinx (e.g., Chappell6

Journal of Language and Literacy Education Vol. 16 Issue 2—Fall 2020& Faltis, 2007; Rodriguez & Braden, 2018), Asians(e.g., Rodriguez & Kim, 2018), and American Indians2(e.g., Bickford & Knoechel, 2017).content analysis permits the addition of specifictheoretical perspectives and lenses to a quantitativecontent analysis. This approach allows for criticaltheories to be combined with quantitative analyses tofoster critical thought. Willis (2008) asserts that notall tenets of a critical theory need to be used for everyanalysis, but rather that the analysis fit a study’spurpose. This article is rooted in the above criticaltheories but is designed to describe the field of theNewbery-winning titles on a large scale. Descriptivecontent analysis allows for establishing an overview,or baseline, of a set of data. Describing the corpus isa necessary prerequisite that must be met beforeconclusions from a critical perspective can be drawn.Adding a critical lens allows for a more nuanceddiscussion of the data. This article is designed toprovide a picture of representations of diversity in thecorpus of Newbery-winning books.The critical lens of GST has been used to analyze thedepiction of gender roles in subsets of books andidentify whether or not the books perpetuatestereotypes (Bem, 1983; Trepanier-Street &Romatowski, 1999). Studies of gender in children’sliterature often examine picture books (e.g., Allen etal., 1993; Crisp & Hiller, 2011; Kneeskern & Reeder,2020) or investigate the influence that children’sliterature has on children’s gender attitudes (e.g.Crisp et al., 2018; Gritter et al., 2017). The notion of“traditional gender roles” is changing incontemporary society, trending toward inclusion ofLGBTQ and nonbinary constructions of gender.Recent scholarship has explored the queering ofchildren’s books for examples of heteronormativityand its impact on identity development (DePalma,2016; Hermann-Wilmarth & Ryan, 2016), as well asstudies that examine representations of LGBTQ characters (Crawley, 2017; Lester, 2014).Research QuestionsThis study examined the representations of diversityin Newbery-winning titles from 1922-2019. It focusedon the following guiding questions:Using tenets of CDT when analyzing literature canassist in identifying hidden biases or ideologicalrepresentations that perpetuate the assumption thatindividuals with physical, emotional, or cognitivedisabilities cannot be a part of general, mainstreamactivities. Research has used CDT to examineportrayals of characters with disabilities and whetherthey are appropriately, accurately, and positivelydepicted (Grow et al., 2019; Leininger et al., 2010).1.What diverse populations are representedwithin the corpus of Newbery-winning titles,and with what prevalence are they portrayedacross categories of race/ethnicity, gender,and disability?2. What diverse populations are representedwithin the main characters encountered inNewbery-winning titles, and with whatprevalence are they portrayed acrosscategories of race/ethnicity, gender, anddisability?Beach et al. (2009) state that, “content analysis is aflexible research method for analyzing texts anddescribing and interpreting the written artifacts of asociety” (p. 129). They discuss how undertaking a2celebrate literature by Native Americans and IndigenousNorth American peoples. The term Middle Eastern wasselected over alternatives (e.g., Western Asian) as it is thetitular term used for the Middle East Book Award.The terms American Indian and Middle Eastern areused in this article. The American Indian Youth LiteratureAward applies the term American Indians to honor and7

Journal of Language and Literacy Education Vol. 16 Issue 2—Fall 2020Methodology2018) books (Koss, 2015) and Caldecott winners (Kosset al., 2018).This study is a descriptive content analysis ofNewbery-winning books. Krippendorf (2004) seescontent analysis as “a research technique for makingreplicable and valid inferences from the text to thecontexts of their uses” (p. 18; emphasis in original).Our coding process was reader-response-oriented(Rosenblatt, 1978) and recognized that texts havemultiple interpretations. The intention in thisparticular analysis of the larger data set was todescribe the presence and prevalence of literaryelements that signaled race/ethnicity, gender, anddisability. To accomplish this goal, we usedsystematic content analysis procedures as describedby Cohen et al. (2007), with an a priori coding system(Weber, 1990).A Priori Variables CodedA list of the a priori variables and coding frameworkused in the present study appear below.Race/EthnicityThe guidelines for race and ethnicity that are appliedin the U.S. Census were employed as part of the apriori coding scheme employed in this study (U.S.Census Bureau, 2017). Race is defined as a person’sself-identification with one or more social groups(asterisked in Table 1) whereas ethnicity determineswhether an individual is of Latinx origin. “MiddleEastern” is not on the 2020 U.S. Census raceclassification scheme; all peoples identifying asMiddle Eastern would either self-identify as “White”or as “Some other race.” Given the large number ofchildren of Middle Eastern descent in U.S. schoolstoday (see, e.g., Parvini & Simani, 2019), this data setcoded specifically for this group.The a priori system was developed and adapted frompreviously used instruments in content analyses. Thissystem allowed for coding variables such as religion,social class, sexual orientation, setting of story (i.e.,time and place), genre, text complexity, the author’scultural identity and sexual orientation—variablesthat are not discussed in the present study—inaddition to variables centered on representations ofrace/ethnicity, gender, and disability—variables thatare discussed in this study. The decision to presentthe analysis and findings related to race/ethnicity,gender, and disability in lieu of the other variablesemanates from (a) the prominence of exampleswithin the data for race/ethnicity, gender, anddisability compared to the limited breadth and depthof examples for the other variable codes, and (b) theobvious connections from the extant literature to ity, gender, and disability. In other words,the coding framework described below offered therichest set of data to discuss and has been previouslyused with large data sets in past content analysesexamining representations of diversity in pictureTerminology was chosen to reflect the terms used bythe major children’s book award committees(American Indian Library Association, 2010; AsianPacific American Library Association, 2010; BlackCaucus of the American Library Association, 2003;REFORMA, n.d.).GenderAlthough acknowledging that coding for gender witha binary, male/female, coding scheme is theoreticallyproblematic and not entirely inclusive or reflective ofcontemporary trends in gender studies, the corpus ofdata reflected the binary scheme with no exceptionsas far as the human main characters were concerned.Gender pronouns, gender-specific language, and/orvisible gender presented in images, when applicable,provided the source information upon which gender8

DIVERSITY IN NEWBERY-WINNING TITLESJournal of Language and Literacy Education Vol. 16 Issue 2—Fall 20201Table 1Race*/Ethnicity ValuesValuesDescriptionWhite*People with origins from Europe or North Africa. White was used to referto any individual not identified as Black, American Indian, Asian, Latinx,Middle Eastern, or Multiracial. Typically, the term White refers to thoseof European descent.Black*People with origin from Africa. Includes people identifying as AfricanAmerican. Black includes all peoples who identify as racially andethnically Black (which might include peoples who identify as African,African American, Caribbean, West Indian, and from other areas).LatinxPeople (from any race) of Hispanic or Latin origin. Latinx includes peoplefrom Latin America, North America, the Caribbean, and other countrieswho self-identify as having Latinx heritage.American IndianPeople of First Nation and Indigenous origins in North, South, andor Alaska Native*Central Americas.Asian*People inhabiting the continent of Asia inclusive of the Far East,Southeast Asia, and India, as well as U.S.-residing Asian-Americans. Asianincludes Asian, Asian Pacific, Asian American, and all other people whoidentify as of Asian heritage.Island Born*People indigenous to Hawaii, Guam, Samoa, or the Pacific Islands.Middle EasternPeople of Southwest Asian, Middle Eastern, or North African countries, orthose U.S.-residing peoples from these geographic regions who identify asbelonging to this group. Middle Eastern includes people from WesternAsia and parts of Northern Africa and Southeastern Europe.MultipleBooks narrated in equal proportion from multiple points of view withdifferent Races/Ethnicities. Only applicable at the Book level.Multiracial*People identifying as having two or more races of origin.UnknownBooks and characters with very specific, yet undetermined, cultural orlinguistic patterns were classified as Unknown.was determined. These guidelines were based onprevious studies (e.g. Crabb & Bielawski, 1994;Weitzman et al., 1972) that identified all characters ofany type—human, animal, toy, magical creature,insect—if they were clearly identifiable in text orimage. If a character’s gender was not clearlypresented by one of the above factors, the characterwas coded as neutral even though such parametersare limiting and potentially problematic, as gender isnot solely a binary construction.DisabilityUnless explicitly specified by an in-text description orlabel, or an adaptive device pre

[ALSC], 2019]). Announcing these awards at the YMA announcements provides greater attention to awards for diverse populations and shows a dedication to recognizing the work of diverse authors and illustrators. The Influence of Newbery Medal Books The John