Transcription

INTERTEXTUALITY: ORIGINS AND DEVELOPMENT OF THE CONCEPTAuthor(s): María Jesús Martínez AlfaroSource: Atlantis, Vol. 18, No. 1/2 (Junio - Diciembre 1996), pp. 268-285Published by: AEDEAN: Asociación española de estudios anglo-americanosStable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/41054827 .Accessed: 14/10/2011 19:37Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at ms.jspJSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range ofcontent in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new formsof scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.AEDEAN: Asociación española de estudios anglo-americanos is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize,preserve and extend access to Atlantis.http://www.jstor.org

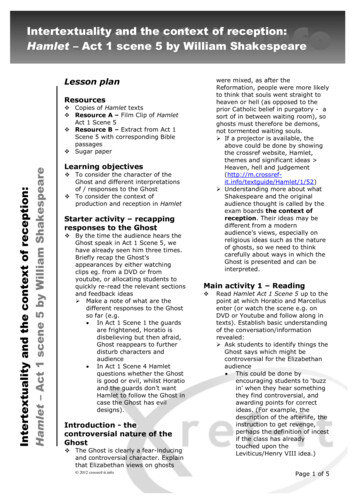

ATLANTISXVIII (1-2) 1996INTERTEXTUALITY:ORIGINS AND DEVELOPMENT OF THE CONCEPT*AlfaroMaríaJesúsMartínezde ZaragozaUniversidadoutinthisessaybeginswitha rriedofthetermasthevariouswaysin to theon Bakhtin'sandKristeva'sroleas ecThedetailedsudyofthewidevarietyofa theoryof aterconstitutesthelastpartoftheessay.critics1. INTRODUCTIONusedinJuliaKristeva'sas a ,essays hetextas a dynamicsitein whichrelationalprocessesand practicesare therthana point(a fixedoftextualDialogue,andNovel",is "anintersection(1980, 65). DevelopingBakhtin'smeaning),as a t"eachword(text)is an exts)whereatleastoneotherword(text)canbe read"(1980,66).Therearealwaysotherwordsina word,othertextsin a text.Theconceptofintertexbutastextsnotas self-containedthatwe cal,as tracesandtracingsof othertextualstructures.and transformationRejectingtheNew Criticalrepetitioninsiststhata ryautonomy,principleas a closedsystem.a etowardstherehaveappeareda widerangeof attitudesFromthisinitialapproach,imandwhatit implies,to suchan extentthatit is jectsor withouttakingintoconsideringpossibletodeal withitwithoutcritics.One of theof literarymadebya etheoriesofintertextualofsucha eaning,andself-containedofthetextas a coherentdissolutionprogressivetexttothewayin whichtextsto a shiftofemphasisfromtheindividualhas led,in sireinLanguage,"Word,DialogueandNovel"is datedin ysein1969.268

69as a termappearedsomethreedecadesago, and thetwentiethThoughintertextualityhasprovedtobe a periodespeciallyinclinedto itculturally,is bynocenturyintertextualityinsomeform,meansa time-boundis atleastas old as e canfindtheoriesandStill1990,2). therehas vaandothertwentieth-centuryto ndRiffaterre,theoristssuchas Genette,Barthes,amongothers.withPlato,itmustbe saidthatin ntopoetryon oppositionBakhtinhimselftohavemuchin commonwithsomemodernapproaches intertextuality.ofwhathe termslocatesin theThe dianovel,heteroglossia,intertextuality.dialogism- whatKristevawill ,typicalcreation, usuallymeanderingtone.Thereis dcharacterizedimage ofofideologiesevoked,butalso in thecentralbivalencenotonlyin h-seekingsavagelyrecallswhatBakhtinwillcelebratein thedialogicnovel.In additionto theformof theinotheraspectsof oftextsas subliminalsuchas icNeitheras wellas inhisviewofimitation.thesubject,In thecase ofPlato,the"poet"alwayscopiesanofnature.as imitationtobe understoodis thecreationdramatica copy.ForAristotle,whichis itselfearlieractofcreation,alreadytoofa ification,reduction,to theoralworksof literaturetheaudienceas well.Thesetextsvaryfromotherwrittenor social codes of conduct.ThoughBakhtinandstockcharactersof myths,traditionKristevasawAristotelianlogicas relatedto themonologicpole of discoursedue to ,emphasison unifiedanduniversalclosetotheofsourcescanbe considereda varietyfromas ourinstinctholdsthatwe zebothCiceroandQuintilianis aninbornworksofimitationinstinct,one's discoursebutalso a consciouslyinis notonlya alpracticeandas theoryofan ationa lsoimpliesanddependsupona ipas re-existentpresupposesphase,revealstheidea of proliferation,exerciseof imitationIn anycase, thestylistictextual.oflanguage.featurewhichis a centralvariation,regeneration,oftexts,also showa retationshouldfitevenifsuchmeaningsofa ybook.If thiswas true,theobjectswhichcomposedtheworldwereaas God's symbolicwrotea ,whenGod ignifiedofNature,but,in addition,bythosewordshad a spiritualATLANTIS XVIII (1-2) 1996

270MartínezAlfaroMaríaJesúswithGod's nd,at a oTheology,whatwas trueofreligioustextswas also madeextensibletosecularones.All literaryworkswereseenas goingbacktotheBibleandall couldbe readlikeit,a viewthatcanbe regardedas a medievalversionofwhatcontemporaryauthorslikeas rgeshaveconceivedmemoryIfGod's stnaturalforindividualwritersto disregardandtotryandemulateGod's perhapsa consciousawarenessofdiscourseas open,unfinished,andsubjecttoan onsinthepastis alwayspresentthroughquotationsworkofsuchwritersas Bacon,Shakespeare,Du Bellay,etc.WhatRonsard,Montaigne,theseauthorsis theglobalityandinfinitein ursesareinscribed,ratherthantheirdebtto previouswriters,whosemeritisseento lie in theirpowerofexpressionandnotin ersdealwiththeworkofthought.Accordingly, wayprecedingauthorsis based on theirbeliefthattheirpossibilitiesof imitation,understoodasand re-writingof the Urtext,are limitless.Only by dependence.Thisis thetheoryforinstance.He believedthatthe"selfproposedbyMontaigne,is tobe foundina (asubjectfromviewmuchin consonancewiththeBloómianconceptof "anxietyof influence")anddefendsa sortofboastfulas stodetachhim/herselffromtheworkofpreviousauthorsas wellasto proclaimhis/herowncreativespacereceiveda ofinterestin originalityBut,in contrastthat,as we d,theMiddleAges andtheseen,dominatedtheeighteenthwithita revaluationoforiginalityas ceptbearingfromtheverybeginningtheseedsofa tof intertextuality.Froman intertextualthereis no wayof consideringperspective,as a traittobe cherishedauthorsorreaders.T. S. hefactthatthemostindividualpartsof an author'sworkmaybe thoseinwhichhis/herancestorsare morevigorouslypresent(1971, 784). etingan ovationprecededwhenstudyinga ngesandenrichesin theitsmeaningIn spiteofhisundeniableinfluenceon theNew Criticism,in thecontextT. S. Eliot,an outstandingofmodernistfigurepoetry,qualifiedin thiswaytheNew Critics'viewoftheworkofartas a ole,a completesystembasedon therelationandiswhichdetermineSuchan dedexemplifiesbySymbolismItcanthereforebe riedtoundermine.andtheperpetualofall worksof processofre-adjustingIn .ATLANTISXVIII (1-2) 1996

INTERTEXTUALJTY:ORIGINSAND DEVELOPMENTOF THE CONCEPT27 1dosesofcultureshakenoutofa falsesenseoffamiliaritywiththepast,tobe administeredshock"(in Kiely1993,19). Butwe also needto be shakenout of a falsesense of ourBorgespointsoutthat"thepresenthasabilitytosee thepast"as itwas". Accordingly,itall thetime"(inhardandrigidaboutit.Butas tothepast,we ccupationKiely1993,17).In tionworksas crowdedwithlayeredimagesof multipleinstead,a viewof literarysuggest,RobertKiely,forinstance,sees adition. It maybeofa coherentthemythtoruptureas ectlythefactthatBeckettteachesus (perhapsforcesus) toreadorrereaddoes s,Whileall �crituredominatesputsit,ré-écriturethinkless of ndsaid,if,ityis bynomeansawriting.originallyculturalitis toitmòrethanothersera,has alreadywitnessedtwo such phases.In the modernistand thatour (Eliot,Joyce),intertextualityapparent aseanshowsPostmodernisminis len'sPlayitAgain,Sam) andarchitecturenowincludes(e.g. CharlesMoore's Piazzad'Italia, New Orleans) (Plett 1991, 26). Riskingsome degree ofworkarenormativeof nesarerange epochs(thesepretextshas as ast,alwaysthecanonizedbetweendistinctionsdownofall assicand pop,artand commerce,theyall are reducedto thesame materials.duringproductionAnyway,disposableof previouslyexistingworks.Thisbecomean act of creationbased on a re-cyclingbeenaccompaniedina elopmentthetheirandoftextsstatustheanda succeededbyan approachbeyondtheas wellas eculture,history society, longerregarded objectiveas literature.ofthesametextualitytextbutas tseparatesapproximationeverypreviousis theviewofas a ifofthetextas a l othertexts",theseareseen,in turn,as converginga extaaasofassystem,subjectis conceived composed discourses, signifyingcametooncethisstepwastaken,sense.No wonder,intertextualityina dynamicthat,then,de vivrehorsdu texteinfini"(Barthes1973b,but"l'impossibilitéas nothingbe ointofview,itis easyto itutewouldofcomplextheory intertextualityATLANTIS XVIII (1-2) 1996

272MartínezAlfaroMaríaJesúsof Bakhtin'stheory,Aristotle,Cicero,Quintilian. can be consideredtheintertextsKristeva's dialoguewiththetextsofBakhtin,in whichshe initiallyuses theterminteris carriedout,in turn,withthemediationoftheworksof DerridaandLacan,textualité,in anyoftheThe ideasexpoundedareequallypresentamongothers.byall ,Riffaterre. . .), andtheywillbe inthoseGenette,stilltocome.approachesIn whatfollows,I as thecrucialmediatorbeginningintertextualtheoriesand thosetraceableantecedents(in ce,thechainwillbe theoneconstitutedwho,as we havenoted,introducedbyJuliaKristeva,thetermin herinterpretationof Bakhtin'sworkfortheWesternpublic,addingto histheorieselementsthatshehadtakenfromsuchfieldsas l1990,16). To endwith,I willanalyzesomeofthelater(Wortontheoriesof intertextualityas theyhavedevelopedfromits firstintroducers.Since thishasofpositionsonthesubjectthatconcernsus,I willnotcentury seensucha widevarietytocoverthematerialbutrathertogivea briefattemptexhaustively,analysis erBakhtinandKristeva.2. THE ORIGINSOF THE TERM: MIKHAILBAKHTINAND JULIAKRISTEVABakhtinstartedpublishingas earlyas 1919, for a varietyof reasonsAlthoughorso yearsthathehasslowlycometo(personal,political. . .) itis onlyoverthelasttwentyberecognizedin rope,His be takenas a(themonologicdialogism)powerfulprecursorof and influenceon the developmentof later approachestointertextuality.Whatcanonlyuneasilybe called"Bakhtin'sis a pragmaticallyorientedphilosophy"ofknowledge,one logiesbehaviourtheusewe ngtheseistheoflanguagethatheproposesas fundamental.specifiedby dialogicconcepts immediateantecedentsaretobe rcomethegap antiansKant's argumentthatthereis an unbridgeablegap betweenmindand worldis therockonwhichdialogismis founded.One ofitsbasicaimsis toframea theoryconceptualof knowledgeforan age whenrelativitydominatesphysicsand cosmologyand,thus,whennon-coincidenceofonekindor anotherraisestroublingquestionsanddoes awaywiththeoldconvictionthattheindividualis thesiteofcertainty,whetherthesubjectsubjectso conceivedis namedGod,thesoul,theauthor. ththe"other":consciousnessthe"self is dialogic,itlivesina relationa centreandall thatisitis rately,ofessentiallynota centre.The self,then,maybe conceivedas a multiplephenomenonand therelationa not-centrethreeelements:a (Holquist1990,29).inhumanbutfora necessarymultiplicityDialogismis thenamenotjustfora dualism,butWe arein s,perception.as "theworld".Inwe lumptogetherandtheculturalalso withthenaturalconfigurationsthatall meaningofthesocial,andtheassumptionis basedontheprimacysum,dialogismis achievedthroughstruggle.ATLANTISXVIII (1-2) 1996

UNTERTEXTUALITY:ORIGINSAND DEVELOPMENTOF THE ewonAnyanalysisofBakhtin'stheoryJustas he triesto avoidansincetheformeris a directof onceptiona viewof languagebut,to use hisword,a "metalinguistics",projectis nota linguisticsis notso mucha moveThismetaposition,withina etowardstranscendenceas itis a battlestance,a polemicaluponsituatingsocial and historicalperiod.Heof theirparticularof languagewithintheconstraintsof traditionalsystematicallyquestionsand subvertsthebasic premisesand argumentsin languageas an abstractandreadyThus,whileSaussureis ssureBakhtinis interestedmadesystem,onlyinthedynamicsto languageas opposedto ationtheAnd whereasSaussuredichotomizesand contradiction.sees a processof struggleis khtinindividualbythesocial,witha social"other".ofdialogueandjuxtapositionis a andnotlanguageas thesubjectofhisinvestigations.Language,as nguists,lexicon,syntaxandphonetics;All thethanthesentence.includea elementsbutas dynamicse featuresmetalinguistics,playa roleas wellinBakhtin'sactsof commuthatcomeintoplayonlyin particularstantdialoguewithotherfeaturesshouldbe addedthoseoflanguagetothestudynication.So, alas dy,bywhichutterancesauthorscancanonlybe r poetry.On theotherhand,at certainhistoricalmoments,monologismwhathe calls tillpointout(1990,15),itis importantnovel.As Wortonto traditionaldo notcorrespondones,forexample,Heine's lyricverseis includedbyas olstoy'sproseis presentedor ordingMonologismorCartesianforcessuchas artraditions,amongin theparodyandrole.It is in popularlaughter,whichthecarnivalplaysa veryimportantofall highgenresandloftymodelsthattherootsofthenovelare to be sought.travestytotheSocraticdialoguesandalso toMenippeansatire,in whichThisappliesin neral,is cworld,is pastandalreadyover,lowgenresand,ina broadsense,a circleinsidewhicheverythingdeal ivecultureof 20). .Moreover,everytimeas uniqueamongall genresduetoitsabilityithastriedto adoptandkeepa ).hasbeenheavily(Bakhtinnovel.However,it is fromtheromanceand thesentimentalwiththechivalryinstance,worksin thethatsomeof themostimportanttraditionsparodyof aid aboutthenovel,whichmustalways be seen as open,free,and in continuousdevelopment.ATLANTISXVIII (1-2) 1996

MartínezAlfaroMaríaJesús274The novel constitutes,forBakhtin,thehighestincarnationof thedialogical play thatcharacterizesall discourse.No utteranceis devoid of dialogical dimension.The only distinctionthatcan be drawnin thisregardis notbetweendiscoursesendowedwithdialogismand thosedevoidof it,butbetweenthetworoles,one weak and one strong,thatdialogismcan be called to play. Yet, at times,he is temptedto inscribeit into a single oppositionwherethe"dialogical" utterancewould face a "monological"one, as is the case withtherelationthathe establishesbetweenproseand poetry(Todorov 1984,63-8).Fromas earlyas thefirsteditionof Problemsof Dostoevsky'sPoetics (1929), and especially in the chapterentitled"Discourse in the Novel", prose, which is dialogical, isopposed to poetry,whichis not. In poetry,language is conceived as unitaryand, conseexternalwithno relationto otherutterancesquently,theutteranceappearsas self-sufficient,to it.The poetfullyassumeshis/herown,as aspeechact and regardseach wordas his/herThe novelist,on theotherhand,does notpureand directexpressionof his/herintentions.exclude the intentionsof others as they are presentin every utterance,and allowsheteroglossiato enterhis/herwork,thuscreatinga unique artisticproductout of such adiversityof voices (Bakhtin 1981, 297-98). Prose and poetryare, then,the resultofand leads to pluralityand variation(thenovel), theopposedtendencies:one is centrifugaland thesingle(thepoeticgenres). Thisotheris centripetaland is ,fortoWhile poetrycontributesits parodiequalityand its oppositionto anykindof authority.of theverbaland ideological worlds,thenovel igins,a de-estabilizingfunctionthatopposes it to officiallanguage. Irreverent,like the carnival, the novel turnsout to be the subversive and liberating genre d liberatingqualityis the novel's capacitytoquestionitselfand itsown conventions(Bakhtin1981, 39). Consideringtheways in whichBakhtin(1981, 412-13) mentionsnovelisticdiscoursemayovertlyappearas self-reflexive,thoseworkscentredon whathe calls "the literaryman", who sees lifethroughtheeyes ofand triesto live accordingto it. Don Quixoteand Madame Bovary are the bestliteratureknownexamplesof thistype,butthe"literaryman"and an be foundin almosteverymajorliterarywork.There are also thosenovels which introducean authorialfigurein the diegesis, someone thatcommentsonhis/hercreative task and on the process of writing(a "laying bare of device", in theterminologyof the Russian formalists).In thatway, we have not only the novel in itsof a sortof "novel about thenovel". Tristrampropersense,butalso fragmentsShandyisperhapsthebestexampleand an importantprecedentof istliterature.Before finishingthissurveyof Bakhtin's ideas on language and the novel, it wouldperhapsbe convenientto call attentionto two aspects of his theorywhichmay be misleading.The firsthas to do withthepositionof theauthorin relationto his/herwork.Ashas alreadybeen noted,in themonologicalgenresthe authorsubordinatesall the voicespresentto his/herown intentions.In a differentway, the prose writerdoes not impose aallows each voice to keep its own insinglecriterionto thereaderbut,on thecontrary,and independence.However,Bakhtindoes notgo so faras to arguethattheauthortegrityis absentfromhis/hertext:thereis no unitarylanguageor stylein thenovel.Butat thesametimetheredoes existaof thecenteroflanguage(a verbal-ideologicalcenter)forthenovel.The author(as creatornovelistwhole)cannotbe foundatanyoneofthenovel'slanguagelevels:heis tobe foundatthecenteroforganizationwhereall levelsintersect.1981,48-9)(BakhtinATLANTISXVIII (1-2) 1996

ORIGINSAND DEVELOPMENTOF THE CONCEITINTERTEXTUALITY:275withwhomhe el,inparticular.on goesbackto whathas alreadybeensaidThe otherpointI wouldliketocommentandmovingtowhichis alwayschanginga presentaboutthenovel'slinkwiththepresent,In spiteofthis,thenovelcan have,andoftenhas,future.wardsan equallyinconclusiveanditsopenchaButevenwhenthisis thecase,thepresentthepastas itscentralsubject.toofthepastis structured.willalwaysbe thebasison whichtheportraitracterAccordingAídaDíaz Bild(1994, 140),thisdirectcontactwithcontemporaryrealityhas importantOneofthemhastodo nsequencesin thecase tationthisnewtemporalIn ithit notonlythemoretheopenqualityof thenovel,sinceliteraryof suchlimits:of changeswithinexistinglimitsbutalso terall, the boundariesbetweenfictionand nonfiction,arenotlaidupinheaven"(Bakhtinandso gof ofa time,a dialoguevoice,a dialoguethattakesplacewithinwhichgivesthosewithall ism,seemstohaveBakhtincreationwhopossessita imtoheardifferencesearthatpermittedhada khtin'sworkfora tionsKristevasubscribedto the nscultural,textual,QuelianIn herview,whatittriedto revoluevenrevolutionary.dynamic,gismas cstructuraltionizedynamicallypoliticsingeneral.of htin, propagating relativitythe carnivalesqueof all dogmaticand officialmonologism,word,theunderminingwas fightingofall authority,againstofall thatis sacredandthesubversionprofanizationand rigidity istRealism.He was,in onsciousnessandunityof individualideologyof sky)withtheprocedureslinguisticsto society:of openinglinguisticsthepossibilityFor ndbythethetextwithinsituates"Bakhtinhistory whichintorewritingandbywriter,she also tin,atte

Bible) the words in it pointed, at a literal level, to the objects in His other book, the Book of Nature, but, in addition, the things signified by those words had a spiritual sense as ATLANTIS XVIII (1-2) 1996 . 270 María Jesús Martínez Alfaro well, since they had been inv