Transcription

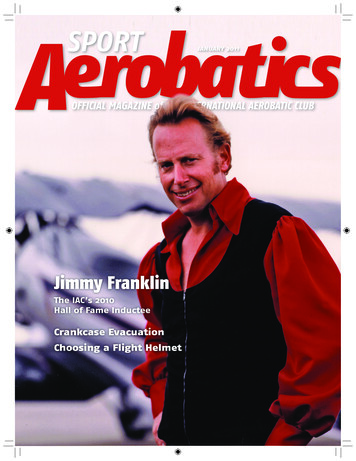

JANUARY 2011OFFICIAL MAGAZINE ofof thethe IINTERNATIONALNTERNAEROBATIC CLUBJimmy FranklinThe IAC’s 2010Hall of Fame InducteeCrankcase EvacuationChoosing a Flight Helmet

CONTENTSVol. 40 No.1 January 2011A PUBLICATION OF THE INTERNATIONAL AEROBATIC CLUBAt age 12, he snuck out and soloed himself while home alone.Features0406122026ImmelmannWhose turn is it?R.E. Van Patten, Ph.D.The CoverJimmy Franklin inhis air show heyday.Jimmy FranklinIAC’s 2010 Hall of Fame InducteeKyle FranklinCrankcase EvacuationMarshal MurrayFlight Helmets and Risk ManagementRick VolkerInside the HangarTechnical TipsColumns02 / President’s PageDoug Bartlett32 / Ask AllenAllen SilverDepartments27 / Advertiser’s Index31 / FlyMart and ClassifiedsPHOTOGRAPHY BY DEKEVIN THORNTON

DOUG BARTLETTCOMMENTARY / PRESIDENT’S PAGEPublisher: Doug BartlettIAC Manager: Trish DeimerEditor: Reggie PaulkSenior Art Director: Phil NortonDIRECTOR of Publications: Mary JonesCopy Editor: Colleen WalshContributing Authors:Doug BartlettR.E. Van PattenKyle FranklinAllen SilverMarshall MurrayRick VolkerReggie PaulkIAC CorrespondenceInternational Aerobatic Club, P.O. Box 3086Oshkosh, WI 54903-3086Tel: 920.426.6574 Fax: 920.426.6579E-mail: reggie.paulk@gmail.comPUBLICATION ADVERTISINGmanager, Domestic:Sue AndersonTel: 920-426-6127Fax: 920-426-4828manager, european/ASIAN:Willi TackeTel: 498841/487515Fax: 498841/496012E-mail: willi@flying-pages.comCoordinator, CLASSIFIED:Alicia CanzianiE-mail: classads@eaa.orgMailing: Change of address, lost ordamaged magazines, back issues.EAA-IAC Membership ServicesTel: 800.843.3612 Fax: 920.426.6761E-mail: membership@eaa.orgEnclosed is a Q&A I hadwith Ryan Birr of theNorthwest Insurance Group,our aerobatic insurancepartners.Doug: I have a series of questions for Northwest Insurance Group(NWIG) that may help our membersunderstand what is taking place withour IAC / NWIG insurance agreement. The end of our three-yearagreement comes up for renewal onApril 1, 2011. I understand Berkleywill not provide aerobatic insurancepolicies after December 1, 2010. Isthat correct?Ryan: That is correct.The International Aerobatic Club is a division of the EAA.WWW.IAC.ORGWWW.EAA.ORGEAA and SPORT AVIATION , the EAA Logo and Aeronautica are registered trademarks andservice marks of the Experimental Aircraft Association, Inc. The use of these trademarks andservice marks without the permission of the Experimental Aircraft Association, Inc. is strictlyprohibited. Copyright 2010 by the International Aerobatic Club, Inc. All rights reserved.The International Aerobatic Club, Inc. is a division of EAA and of the NAA.A STATEMENT OF POLICY The International Aerobatic Club, Inc. cannot assumeresponsibility for the accuracy of the material presented by the authors of the articles in themagazine. The pages of Sport Aerobatics are offered as a clearing house of informationand a forum for the exchange of opinions and ideas. The individual reader must evaluatethis material for himself and use it as he sees fit. Every effort is made to present materials ofwide interest that will be of help to the majority. Likewise we cannot guarantee nor endorseany product offered through our advertising. We invite constructive criticism and welcomeany report of inferior merchandise obtained through our advertising so that correctivemeasures can be taken. Sport Aerobatics (USPS 953-560) is owned by the InternationalAerobatic Club, Inc., and is published monthly at EAA Aviation Center, Editorial Department,P.O. Box 3086, 3000 Poberezny Rd., Oshkosh, WI 54903-3086. Periodical Postage is paid atOshkosh Post Office, Oshkosh, Wisconsin 54901 and other post offices. Membership rate forthe International Aerobatic Club, Inc., is 45.00 per 12-month period of which 18.00 is forthe subscription to Sport Aerobatics. Manuscripts submitted for publication become theproperty of the International Aerobatic Club, Inc. Photographs will be returned upon requestof the author. High-resolution images are requested to assure the best quality reproduction.POSTMASTER: Send address changes to Sport Aerobatics, P.O. Box 3086, Oshkosh, WI54903-3086. PM 40063731 Return undeliverable Canadian addresses to Pitney Bowes IMS,Station A, P.O. Box 54, Windsor, ON N9A 6J5.2 Sport Aerobatics January 2011Doug: Were they required to provide us insurance policies until theend of our agreement?Ryan: No, the agreement for services was directly with NWIG andnot with Berkley, they are under noobligation to provide the product.They did, however, agree to carry theprogram through December 1, 2010,as a courtesy to us and the IAC.Doug: Will NWIG be able to provide IAC members with competitiveaerobatic policies?Ryan: We have been working hardto find homes for members thatwon’t have Berkley as an option onrenewal. Since we have the entireaviation market (except AVEMCO)to work with, we have been relatively successful finding IAC members an insurance product to meettheir needs at a competitive price.The coverage forms are vastly different from one company to the next,so our job has really been to makesure coverages are in place for thetype of flying that each insured isinvolved in. We are more than happyto continue to provide our brokerageservices and insurance counsel to IACmembers. We’ll have to look at theservices contract to determine thebest way to move forward, since wewon’t have an exclusive product from12/01 forward, which our contractwith IAC requires.Doug: Why did Vicki Cruseapproach NWIG to establish aninsurance program?Ryan: Vicki approached us to bidon the then-expiring contract withthe previous program provider. Sheconducted a member survey thatPlease submit news, comments, articles, or suggestions to: reggie.paulk@gmail.com

showed 1) the members were unhappy with the service from the brokerage and 2) that the product wasn’tdoing everything that the IAC wantedfrom its insurance program. She waslooking for a program that would benondiscriminatory towards the various aircraft that were involved in IACcompetition, which would provide ahost of additional coverages in addition to basic hull and liability (memberbenefits), which would also providecoverage when aircraft went to foreigncountries for competition, and, finally,would provide a reasonable revenuestream back to IAC. She was also looking for an exceptional level of serviceto the membership from the provider.lots of coverages, and significant financial support. The key here was thatit was a “true program” with pooledunderwriting; if claims expense washigh then premiums would increase.If they were low, premiums woulddecrease. The program would take allIAC aircraft, nearlyall pilots, in all conditions, and coverthem anywhere inthe world.Doug: Why did Berkley pull outof providing the IAC with aerobaticinsurance policies?Ryan: Claims andprogram expensesexceeded initial estimates. We did notget the participation that Vicki originally thought we would, and the claimsgrew to unacceptable proportions. Thepricing simply followed claims experience. Premiums went up three separate times due to claims experiencein the program. Additionally duringthe past year, as members started toleave for lower pricing, then the program’s profitability quickly eroded,creating a spiral effect. This is not anunusual phenomenon with insuranceprograms though; some programs dosurvive if participation is garneredsoon enough in the program’s infancy.Ryan: I can only speculate on thereal reason but 1) the cost of theprogram (losses versus premium) wasclearly too high. The participation inthe program by the IAC membershipwas lukewarm considering our 3 yearsof involvement with the Club and themassive amount of promotion we did.So, the combination of low premium volume and policy count combined with high claims expense in theend necessarily warranted Berkley’sexit simply on an economic basis.Insurance companies work for a profitand we had three years to deliverprofits to Berkley it didn’t work outso well.Doug: Did Berkley provide IACmembers with a superior product ata fair price?Ryan: NWIG was able to negotiatean exceptionally comprehensive policyform, low pricing, worldwide territory,Doug: Why wasthere a large swing inthe cost of insurancepolicies over the lastthree years?Doug: Is there any reason the IACshould work directly with insuranceagencies to provide insurance optionsfor its members?Ryan:Thatdepends on whetheror not you can convince an insurancebrokerage to pay royalties and extensiveadvertising costs. Ifwe have a dedicatedprogram or we otherwise just marketthe accounts, we stillprovide a substantialservice to the IACmembers regardingcoverages for theiractivities, whetherit’s for practice, for competition, forsightseeing, or dual instruction, orfor air shows. But we can do thatindependent of the IAC contract, inwhich case the IAC loses all its revenuefor our services. IAC needs to decidehow much it is willing to promote thisservice (we or others provide) as amember benefit in order to generaterevenue for the Club. We do know thatwe have given a substantial amount offinancial support to the IAC as part ofthis contract during the past 3 years.I can’t imagine why the IAC wouldn’twant a brokerage involved in somecapacity in order to continue receivingfinancial benefits from such a service,even if it’s not NWIG.Since the“program” isnow concluded,we are forcedinto marketpricing.Doug: Can we receive a similarproduct from other insurance providers at a competitive price?Ryan: Since the “program” is nowconcluded, we are forced into marketpricing. In other words, the pricingthat members receive is now what isavailable in the open marketplace andPlease send your comments, questions, or suggestions to: dbartlett@eaa.orgno program pricing is available.If anybody has any questions orwould like to discuss this issue further, I can be reached by email at doug.bartlett79@gmail.com or by phone 847875-3339. Fly safe and keep plenty ofaltitude below you! IACwww.iac.org 3

Max Immelmann andhis dog (note “theBlue Max” just belowMax’s collar).ImmelmannWhose turn is it?by R.E. Van Patten, Ph.D.Max Immelmann was one of the first Germanfighter aces of World War I. He began pilottraining in November 1914. Initially assignedto liaison flights servicing German aerodromes,he soon moved on to recon missions. He was shot down for4 Sport Aerobatics January 2011the first time in June 1915 and landed within his own lineswithout injury. Shortly thereafter Fokker’s new monoplane,the Eindecker E1, was introduced. It was equipped with amechanism to synchronize the machine gun with the engineto permit firing through the arc of the propeller.Max and his

squadron mate Oswald Boelcke startedthe “Fokker Scourge” flying this aircraft.Scoring against a British B.E.2cbomber on August 1, 1915, Max earnedthe Iron Cross first class; he stalkedhis victim all the way to the ground,landed, shook hands with the pilot,and took him prisoner. He scored morekills in September and survived beingshot down by a French farmer. By earlyDecember, Max had run his score up toeight and was being acclaimed as DerAdler von Lille (The Eagle of Lille); Maxliked patrolling over the town of Lille.After both Max and Oswald had scoredtheir eighth victories, they were awarded the ultimate decoration of ImperialGermany, the Pour Le Mérite, followingwhich it was dubbed “the Blue Max.”The name “Max Immelmann” haslong been associated with a maneuvercalled the Immelmann turn. The modernaerobatic competition Immelmann turnconsists of a half-loop from level flightand a half-roll to upright at the top ofthe loop, with a consequent 180-degreereversal in the direction of flight.What is now known as the Immelmann turn would probably have resulted in a fatal accident if attempted in theplanes Max flew.The Fokker monoplane in 1915 stillused wing warping for roll control, andthose who flew it and survived describedits handling and stability as “tricky.” Ina personal communication [1], authorMike Hawkins described the shortcomings of wing warping as a means of rollcontrol and commented, “With the Fokker, the aircraft would be at or belowstall speed at the top of the half-loop,and application of wing warp to roll outwould result in unpredictable directionand rate of roll, most probably leadingto a spin! Recovery from a spin wasnot understood in 1915, and it is mostunlikely the pilot would have survived.”A controversy continues over whoactually invented this style of fighting, since Max stated, “I do not employtricks when I attack.” Nothing in his letters or memoirs indicates that he originated the half-loop, half-roll maneuvernow named after him.At least one source has suggestedthat Allied pilots later used the modern version of this maneuver to escapeMax Immelmann—“the Hun in thesun”—in the initial high-side diveportion of his attacking stylefrom Max [3]. Given a target equippedwith aileron roll control and with sufficient energy to do it, a half-loop,half-roll maneuver would have been anexcellent tactic for defeating Max’s preferred repeated diving/zooming/hammerhead stall style of attack and wouldcertainly have left Max out of airspeedand options.The style of attack Immelmannused was the first application of vertical maneuver in air combat, and hedeserves his place in history for thatinnovation [5] [4]. Although initiallyshocking to Allied pilots, it soon cameinto common use on both sides inWorld War I. However, as more powerful engines became available, it lostmuch of its initial advantage, since atthe top of the zoom in a hammerheadstall the attacker provided an almostmotionless target with only one energy option.Max died in air combat with a twoseat Royal Aircraft Factory F.E.2b onJune 18, 1916. Accounts of his deathvary. In his account [2], Franz Immelmann (Max’s brother) describes whatreads like a serious structural failurein the section of the fuselage aft of thecockpit, with a portion of the airframelashing back and forth. This might havebeen damage inflicted by machine-gunfire from the British plane. He alsoreports that it’s probable the enginemount had also failed, owing to thedestruction of the propeller and theresulting high unbalanced loads. Thishad happened to Max at least oncepreviously with a synchronizer failure.Franz Immelmann [2] verified that anexamination of the wreckage of hisplane revealed a failure of the gun synchronizer gear, since his propeller wasshot to pieces exactly in line with hisown guns [3]. Ironically the technology that made him an ace also probablykilled him.A fitting posthumous tribute to Maxdeveloped during the Vietnam War. TheU.S. Air Force Tactical Air Commandissued an order to disable the rudderlimiter on the F-5. When in flight,with the gear up, this limiter restrictedthe F-5 rudder to 6 degrees of deflection. With the gear down, this limiter was changed to permit 30 degreesof deflection. The modification to thehydraulic system and controls was subsequently carried out, and the F-5 suddenly became the most maneuverablefighter in the air. Pilots very quicklystarted exploiting the same maneuverthat Max used—but with a difference.In a head-on merge, for example, it wasused to avoid falling into the sustained“knife fight in a telephone booth” ofthe rolling scissors scenario. By usingthis vertical maneuver at the merge to“out-turn” the adversary, an immediateposition for a stern attack was gained.This maneuver is now called the “highyo-yo” and is probably one of the firstmaneuvers taught to the novice fighterpilot [6].IACReferences[1] Hawkins, Mike. Personal communication. Nov. 18, 2004.[2] Immelmann, Franz. The Eagleof Lille. Presidio Press, 1990.[3] www.acepilots.com/wwi/gerimmelmann.html[4] Spick, Mike. The Ace Factor.Naval Institute Press, AvonBooks. 1989[5] Spick, Mike. Fighter Pilot Tactics: The Techniques of DaylightAir Combat. Patrick Stevens Ltd.[6] Shaw, Robert L. Fighter Combat Tactics and Maneuver. NavalInstitute Press.www.iac.org 5

6 Sport Aerobatics January 2011

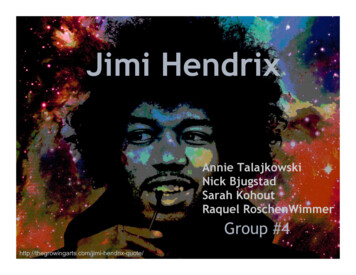

Jimmy FranklinIAC’s 2010Hall of Fame inducteeby Kyle Franklin with Reggie PaulkThe attention of the spectators is drawn toa thin ribbon of smoke trailing down from the bluesky; the deafening roar of a 450-hp Pratt & Whitney radial engine on a large black and silver biplanecomes over the threshold. Rolling inverted, the pilotallows the vertical fin to sink to within 4 feet of therunway. At 185 miles per hour, he picks up a ribbonbeing held by two men and streaks past show center,still in the inverted position, the ribbon streamingfrom the tail. This was Jimmy Franklin.Few men can write their own destiny. JimmyFranklin happened to be one of a rare breed. Bornin 1948, he was raised on a ranch near Lovington,New Mexico. Jimmy started learning to fly whilestill in diapers, sitting on his father’s lap as theyflew 30 miles between their farm and ranch. Whenhe was 8 years old, Jimmy was capable of flying.At age 12, he snuck out and soloed himself whilehome alone. That same year, after viewing his firstair show, he began teaching himself aerobatics froma book. Flying aerobatics over the next seven yearslaid the foundation and development of a man farbeyond his years. In 1967, at age 19, Jimmy boughta stock 1940 Waco UPF-7 and began performing airshows in it that same year.Over the next 38 years, Jimmy and his Wacowould thrill audiences all over the world. He performed in Canada, Mexico, Japan, and even Australia. Jimmy’s artistry can also be seen on the silverscreen and countless television shows, such as Terminal Velocity, Forever Young, The Rocketeer, ThreeAmigos, and Choke Canyon.At age 12, he snuck out and soloedhimself while home alone.www.iac.org 7

DEKEVIN THORNTONDuring this time, Jimmy introduced more than 20 unique air showacts in 10 different aircraft. A few ofthese acts included a routine with EliotCross named “The Dueling Wacos,”with dual wing-walking routines andcomedy acts. Jimmy created a character called “ZAR,” in which he portrayeda comic book/space age character flying a black and silver, twin-engineAerostar, the Starship Pride.Always a true showman, Jimmywas recognized and honored manytimes during his years as an airshow professional. He received thecoveted Bill Barber Award for Showmanship in 1989; the Clifford W.Henderson Achievement Award in1999; the General Aviation Newsand Flyer Reader’s Choice Award forfavorite overall performer and favorite specialty act in 1990 and 1996;and the ICAS Foundation Air ShowHall of Fame in 2007. Jimmy was thefirst person to receive the Art SchollShowmanship Award in 1986 for hisZAR act. He received the award a second time in 1999 for his showman8 Sport Aerobatics January 2011ship in his Jet-Waco, making himthe first and only person to receivethe Art Scholl Showmanship Awardtwice. In 1999, Jimmy debuted hiscrowning achievement: the world’sfirst and only jet-powered Waco.With the help of Les Shockley, creator of the “Shock Wave” jet truck,they were able to mate a CJ610(J-85) jet engine along with the 450hp Pratt & Whitney radial engine toJimmy’s Waco biplane. With an airshow weight of 3,200 pounds andboth engines turning, the Jet Wacoput out more than 4,500 pounds ofthrust and more than 2,000 hp, giving a vertical climb rate of more than10,000 feet per minute. In Jimmy’shands, this 1940 Waco was able toperform stunts no one has ever seenor even attempted in this type ofplane. He added a wing-walking actwith his son Kyle, who became theworld’s first jet wing walker.In 2002 Jimmy, his Jet-Waco, anda few of his closest air show friendsredefined the term “air show” by forming the infamous X-Team, which gavebirth to the “Masters of Disaster” orM.O.D. Their act quickly became thewildest and most talked about airshow act in the aviation community.Tragically, Jimmy and longtimefriend Bobby Younkin were bothlost while performing the Mastersof Disaster, at a show in Canada in2005. Jimmy was 57 years old.During his lifelong aviation career,Jimmy would reinvent and changeair show entertainment over andover again while amazing and inspiring thousands of people young andold. He was known to say, “WhenI was 12 years old I decided I wasgoing to become an air show pilot,and here I am this many years laterstill trying to become one.”There is no doubt Jimmy Franklinleft his mark on the aviation world.Anyone who saw him fly would behard-pressed to forget his performances for their constant pushing of thelimits of both airplane and pilot. To geta better look inside the life of JimmyFranklin, you have to talk to his sonand air show colleague, Kyle Franklin.

DEKEVIN THORNTONIn 1999, Jimmydebuted his crowning achievement: theworld’s first and only jet-powered Waco.Accepting the Hall of Fame Awardon his father’s behalf, 30-year-oldKyle Franklin is himself an accomplished aviator. When Kyle lost hisfather in 2005, he was only 25 yearsold, but he’d already spent sevenyears performing wing walking andair show acts with his dad. WhenKyle was born in 1980, his fatherhad already been flying air shows for23 years. His is a unique perspectiveof a man whose lifeblood was the airshow season.“My dad flew air shows for over 38years, and I naturally grew up aroundair shows and airplanes,” says Kyle.I knew from a very young age myfather was one of the better air showpilots out there. He was good at whathe did, and I was always proud ofeverything he’d done.”In the 38 years he performed airshows, Jimmy created more than 20unique acts. For one of the acts, hecreated a space-age comic characterdubbed ZAR. Flying a twin-enginePiper Aerostar, Jimmy would dressin a black costume complete withhelmet and cape. At the time, 4-yearold Kyle was instrumental in thecharacter’s design. “He used me ashis test subject,” says Kyle. “He wasgearing the act toward children, andit was the whole Star Wars era in theearly ’80s. He would try out differentcostumes and ideas to see what his4-year-old son thought.”At the time the ZAR act was created, no one had ever seen anythinglike it. “The kids and adults alike atethe act up,” Kyle remembers. “Whenever he’d come out in that black outfit with the helmet on and the wholeback story, you couldn’t hardly pullhim away from the crowd. It was anamazing act flyingwise, with all theshowmanship involved. It was stillgoing strong when Dad retired it in1991.” Jimmy and Kyle discussedbringing the act back many times inthe intervening years, and Kyle sayshe’s young enough that it could comeback someday.Jimmy Franklin considered the’80s to be the heyday of the airshow business. During that time, hewas crisscrossing the country—flying three to four different airplanesat 35-40 shows a year. “He had theWaco Mystery Ship and the Waco600,” Kyle says. “He had the Aerostar for ZAR and the Super Cub for amotorcycle transfer and comedy act.”When Kyle started school in 1985,he and his mom weren’t able totravel to air shows with Jimmy. Kylewent to school and attended whatair shows he could. When he turned12, he decided to begin travelingwith his dad every summer. “I wouldtypically finish up my last final atschool,” he says. “And then, the nextday, catch an airline out to whateverpart of the country he was out airshowing. I did that from the time Iwas 12 years old pretty much until Igraduated from high school.”Jimmy taught Kyle to fly in muchthe same tradition that he’d learnedhimself. “He taught me just abouteverything I know now,” Kyle continues. “All of the things I do in mycomedy routine are things I learnedto do in the Super Cub with mywww.iac.org 9

JIM KOEPNICKFor 38 years, JimmyFranklin thrilledcrowdsat air shows.Kyle and Amanda during an air show performance.dad. He focused a lot on groundcontrol, knowing the airplane, notbeing afraid of it. I learned that at 9years old.”Kyle first practiced wing walking when he was 14 years old. “I gotbored at a show,” he says. “I’d beenbugging him for a while to do somewing walking, and I’d been practicinga lot on the ground. We went up theFriday before a show; I crawled outof the front cockpit, climbed up ontop, and stood on the top wing.”Three years later, Kyle was 17years old and finishing up his lastyears of high school. The wingwalker Jimmy was working with atthe time quit at the beginning ofthe season, and there weren’t any10 Sport Aerobatics January 2011alternates. Kyle suggested he wingwalk for the season until they couldfind someone else. “He wasn’t reallykeen on that idea,” he says. “He hadto think about it for a couple ofweeks. We sat down and discussedall of the risks involved, and eventually, I did my first professionalwing-walking show.”Since Kyle was still in school, hewould take a half-day off on Friday,hop on an airliner to wherever hisfather was flying, spend the weekend wing walking, and then jet backhome Sunday evening so he could goto school on Monday morning. “Itdefinitely beat working at the localfast-food joint,” he says.Jimmy was known for pushing theDEKEVIN THORNTONenvelope, and it earned him the dubious distinction of being the only airshow performer to get red-flared atOshkosh. In 1975, many air show aircraft were not equipped with radios,so the air boss would shoot a red flareif he saw something he thought to beunsafe. In no uncertain terms, the flaremeant to get your butt back on theground immediately. This was Jimmy’sdebut at Oshkosh, and the 27-year-oldpilot made a decision that cost him acouple seasons of air showing.“He was taxiing to takeoff,” saysKyle. “Someone comes running outand tells him they don’t want him todo his ribbon pickup. They’d briefedit and everything was okay, so heasked why not. The person said they

didn’t know; they just didn’t wanthim to do the ribbon pickup. My dadhad two people hold a ribbon about6 feet above the ground. He wouldfly inverted and pick it up with histail. It kind of pissed him off, so hewent out there and beat the groundreally good and did an aggressiveroutine. At Oshkosh, there’s a littleravine between the runway and thetaxiway. On his last pass, he rolledupside down and sank into thatravine, and more than half the taildisappeared. He had a 4-foot wireon the rudder to catch the ribbon,and when he pushed out, he endedup with grass on the wire. They shotthe flare, and that stunt wound upcosting him three years in the airshow business more or less. In 1975,he had his biggest season, with 18shows. He did six the next year. Istill have footage of that flight onhis tribute DVD.”In the end, the air show business is all about thrilling the crowd.“We’re always trying to get yourattention—get your adrenalinegoing,” Kyle says. “Most of the time,it’s smoke and mirrors and illusiontrying to get that thrill out of you.”For 38 years, Jimmy Franklinthrilled crowds at air shows. Theprecious little time he did get duringthe off-season was spent preparingthe airplanes and creating new acts.He did engage in a few hobbies, however. “He liked old Western stuff,”remembers Kyle. “He had a hugecollection of old Aladdin lamps. Healso liked Winchester rifles and Coltrevolvers. I still have most of hiscollection of lamps because I thinkthey’re pretty neat as well.”When Jimmy Franklin was 12years old, he saw Harold Krier andCharlie Hillard perform at his firstair show. “It was a defining momentfor my father,” says Kyle. “After hewatched that air show, he startedgetting airplane magazines. He wasthumbing through an antique airplane magazine, and on the centerfold that particular month wasa Waco UPF-7. He thought it wasthe coolest airplane he’d ever seen,so he pulled the center section andhung it on his wall. His mom eventually had it framed and put it backup. When he was 19, he and hisfather had gone to an air show asspectators. As they were leaving theshow, Jimmy noticed an airplanethat looked kind of familiar. It was aWaco UPF-7. It turns out, it was theexact same airplane he’d hung on hiswall: N2369Q. They bought it on thespot for 4,500 dollars. Jimmy flewit home, started practicing with it,and flew his first air show that year.Over the years, the airplane changedand had other parts put in it. Itwould eventually become the JetWaco and was the airplane he wasin the day of his final flight. He wasdestined to find that airplane and dowhat he did. What are the chances offinding the airplane you fell in lovewith at 12 years old, had hanging onyour wall, and then use it in your airIACshow career?”www.iac.org 11

Exhaust-DrivenCrankcaseEvacuation SystemsAn extremely reliable processby Marshall Murray, Sky Dynamics CorporationPhotos courtesy Sky DynamicsUsing exhaust flowto extract enginecrankcase pressurehas significant positive effects in piston aircraft applications. These benefits range fromengine efficiency improvements tothe general maintenance improvement of reducing oil leaks and theever-important aesthetic improvement of keeping the breather oilfrom soiling the belly of the airplane. Over the last 30 years of exhaust system development at SkyDynamics, we’ve advanced the interaction of the crankcase evacuationsystem into our collector-style exhaust systems to the point that it’snow standard on all exhaust applications—whether it’s a custom lightweight system for Sean Tucker’s newplane or a production Cub Crafters12 Sport Aerobatics January 2011light-sport aircraft system. Throughin-house testing and our history ofworking with the top aerobatic andrace pilots, we’ve been able to evolvethe design details and the manufacturing process to make the systemextremely reliable. Along the way,we’ve also found the system to possess other unique benefits.The success behind our crankcaseevacuation system is that removingthe positive crankcase pressure whichbuilds up due to normal combustionleaks causes the engine to operatemore efficiently. This efficiency increase manifests itself as a lower fuelburn, an increase in ultimate power,and an increase in longevity. The increase in efficiency is derived fromthe many positive effects of the depression that is created inside thecrankcase. The first positive effect isthe reduction of pumping resistance

FeATures Columns DepArTmenTs 04 06 12 20 02 / President’s Page Doug Bartlett 32 / Ask Allen Allen Silver 27 / Advertiser’s Index 31 / FlyMart and Classifieds THe Cover Jimmy Franklin in his air show heyday. ConTenTsVol. 40 No.1 January 2011 A PUBLICATION OF THE INTERNATIONAL AEROBATIC CLU