Transcription

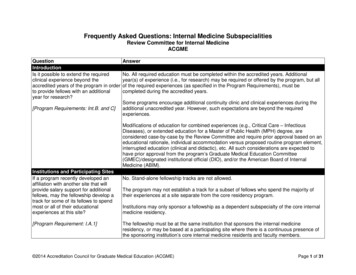

-----

Cover:Title page from Dr. John Jones' PlainConcise Practical Remarks on theTreatm ent of Wounds and Fractures ,1775. Thi s was the first full-lengthmedical book written by an Americanand published in this country.

200 YEARSof American Medicine(1776 -1976)In recognition of the nation's bicentennial, theNational Library of Medicine is presenting anexhibit honoring selected American achievementsin medical science and practice and outlining thedevelopment of medical education, medicalliterature, and public health in the United States.Themes of the exhibit are described in the followingpages.U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, EDUCATION, AND WELFAREPublic Health ServiceNational Institutes of HealthDHEW Publication No. (NIH) 76-1069

Physicians . '/l//?1./t.ll/1/ ./, /'/(

and the RevolutionMany American physicians played animportant role, both politically andprofessionally, in the winning of Americanindependence.A decade in advance, John Morganexpressed the feelings of many young menwhen in 1766 he warned against oppression ofAmerican liberties . Morgan later becameDirector General of the medical departmentof the Continental Army . Joseph Warren ofBoston was a leading figure in patriotic circlesthat included Samuel Adams and JohnHancock. He was killed at the Battle of BunkerHill. Benjamin Rush, one of the mostptomi nent American physicians of his dayand three other physicians signed theDeclaration of Independence. Immigrants,like Bodo Otto from Germany, and youngmen later to become leaders of theprofession , like James Thacher and JamesTilton, also supported the American cause.Regrettably, the colonies ' leadingphysicians were often a quarrelsome lot, andthe history of their service is marred by thebitter feud between Morgan and hissuccessor William Shippen. Nevertheless,Morgan and Rush found time to issuepamphlets on military medical problems,while others issued more substantial workslike John Jones on military surgery andWilliam Brown's pharmacopoeia .Two major European nations were alsoactive in the fighting; our ally France and ourenemy England. Both had comparatively welldeveloped military medical services, theFrench under their distinguished physician in-chief, Jean Francois Coste. British accountssuggest that their record for maintaining thehealth of the troops was considerably inadvance of the Americans'.On the preceding page is reproduced a le!!er fromGeorge Washington to " The Honorable j oseph jonesEsq . of Congr ess at Philadelphia. " The o rigina l is in thecoll ection of the Nationa l Library of Medicine's Hist ory ofMedicine Division. Th e text follows.to you, that I think Doctors Craik and Cochran from th eirservi ces, abilities and experi ence, and their closeattention , have the strictest claim to their co untry'snotice, and to be among the first officers in theestablishment.There are many other deserving characters in themedical line of the army, but the reasons for mymentioning the above gentleme n are, that I have thehighest opinion of th em , and have had it hinted to methat the new arrangement might possibly be influencedby a spirit of party out of doors (i.e., partisan politics],wh ich would not operate in their favor.! will add no morethan that I amHead Quarters Sep. 9th, 1780Dear Sir:I have heard that a new arrangement is about to takeplace in the Medical Department, and that it is likely, itwill be a good deal curtailed with respect to its presentappoint ments.Who w ill be the persons generall y employed I am notinformed, nor do I wish to know ; however I will mentionWith the most perfect respectDear SirYour most obed ient serva ntG. Washington

Medical EducationWith the achievement of politicalindependence, Americans still had far to go toreach an equal degree of intellectual andcultural independence. Still heavilydependent on Europe, American physicianshad made only slight beginnings in thedevelopment of American institutions . Oneof the first needs was the capability ofeducating physicians in our own country.Before the Revolution, practitioners weretrained chiefly by apprenticeship; a few whocould afford the time and expense traveledabroad for further education. In 1765, johnMorgan and William Shippen of Philadelphia,both graduates of Edinburgh, founded thefirst medical school in the country, now partof the University of Pennsylvania. Additionalmedical schools were founded at KingsCollege (now Columbia University) in 1768and at Harvard in 1783. In the 19th century,however, groups of physicians throughoutthe country began founding small proprietarymedical colleges, dividing among themselvesthe lectures and student fees. Entrance andgraduation requirements were sufficientlylow to insure a steady income. Laboratory andclinical facilities were woefully inadequate.Large numbers of poorly trained physicianswere released to practice on the public.As a result, the abler and more ambitiousstudents continued going to Europe. Early inthe 19th century Paris hospitals were themajor attraction; after the Civil War,Americans flocked to Austrian and Germanuniversities, some to learn a clinical specialty,others the basic sciences. As increasingnumbers returned with an awareness of goodteaching and above all of the possibility oftransforming both teaching and practicethrough close association with research,scientific medicine began to evolve in thiscountry.Reforms were also being instituted byeducational leaders from outside the medicalprofession. In the 1870s President CharlesEliot of Harvard introduced a gradedcurriculum into the medical school ,lengthened the course from two to threeyears, elevated the entrance requirements,and substituted part-time salaries paid by theuniversity for direct payment from studentfees .

Under the educational leadership of DanielCoit Gilman, the new Johns HopkinsUniversity in Baltimore emphasized graduateeducation in research. The medical school,opening in 1893, was conceived as part of theuniversity and closely integrated with theJohns Hopkins Hospital. In addition toupgrading undergraduate medicaleducation, the Hopkins originated theresidency training system.Pub I ic and professional concern formedical education culminated in a survey ofall the medical schools by Abraham Flexnerunder the auspices of the AMA Council onMedical Education and the CarnegieFoundation for the Advancement ofTeaching. His report, Medical Education inthe United States and Canada (1910), hadimmediate and far-reaching impact. Therewere then 131 medical schools in the UnitedStates, most of them proprietary. By 1920,46had closed or were absorbed by strongerinstitutions. Others were strengthened bymerger, by university affiliation, and by theinfusion of support from private foundationsand state governments.By the 1920s the four years of medicalschool were compartmentalized into twoyears of basic sciences taught by disciplineand two years of clinical training. Since the1950s increasing emphasis has been placed onteaching basic concepts in a program plannedby interdisciplinary subject committees andtailored, in part, to the individual student'sinterest.An important factor in recent changes isthe growth of federal support for medicalresearch, mostly in medical schools, from 27million in 1947 to 1.4 billion in 1966. In 1968 69 approximately one third of faculty salarieswere paid from federal sources. The impact ofthis federal support was generally favorablealthough some cr1t1cs claim thatconcentration on' research has divertedfaculties from their primary mission ofdeveloping physicians. The present decreasein federal support, the abundance ofspecialists, and the shortage of primary-carephysicians seem to assure continuingmodifications in American medicaleducation .Abraham Flexner (1866-1959)William H. Welch (1850-1934)

Medical LiteratureClosely linked to the development ofmedical education, and equally important forthe advance of medicine in this country, wasthe growth of suitable means for recordingand disseminating new medical ideas andinformation .The first purely medical publication in thiscountry was a broadside by the ReverendThomas Thacher, A Brief Rule to Guide theCommon People of New-England How toOrder Themselves and Theirs in the SmallPocks or Mea sels, Boston , 1678. Most colonialmed i cal publications were pamphlets.Physicians who wished to publish scientificobservations generally submitted them to anEnglish journal.The first American medical journal , TheMedical Respository, was started in New Yorkin 1797. In the half century following , thenumber gradually grew. Monographs alsoappeared in increasing profusion , althoughmost of the best ones were reprints andtranslations of books published abroad . In1848 the Committee on Medical Literature ofthe AMA, chaired by Oliver Wendell Holmes,identified twenty American medical journals.With rare exceptions, such as the Americanjournal of the Medical Sciences, theCommittee found them wanting and stressedthe need for more conscientious editing andthe elimination of unworthy articles andparasitical authorship. Similar criticisms wereleveled at monographs.The quality of American medical literaturemarkedly improved with the growth ofscientific medicine in the late 19th century. Asphysicians returned from graduate training inAustria and Germany, their reports of clinicaland laboratory research upgraded existingjournals and created a need for new onesdevoted to the specialties . One of the earliestwas the journal of Experimental Medicine,established in 1896.In the 20th century the tables turned .American texts are translated into foreignlanguages . The number of journals ofbiomedical interest has grown in 100 yearsfrom less than 50 to more than 700.Improvements in medical education , thegrowth of medical specialties , and thecontinuing expansion of basic research haveplaced the American medical literature in aposition of primary world importance.

'" .'A.J{·J ,W: -- -.: JrfJ"o [!MiltJ.f:lllffiiM · 'Ptop/ufN E·,W·E N G L A N D., i· Ho· to Ol'dcr \bcmCclYn and th 1rs in 1hc.SmallPoc s,L .or Meafels.

Public HealthIn the application of medical knowledge,public health organizations have played avital role in improving the health of thenation.Most early public health activities wereconducted on a part-time basis at city, town ,and village levels. However, in 1850 LemuelShattuck urged Massachusetts to form a stateboard of health to encourage and coordinatelocal fforts. When finally established in 1869,the Massachusetts State Board of Healthbecame the model for other state healthdepartments .By mid-century also, recurring cholera andyellow fever epidemics indicated a need forcoordinating sanitary measures among thestates. The National Board of Health ,established in 1879, was an early effort toprovide the Federal Government with on going professional advice on these and otherhealth matters, but its ambitions for anextensive national health role werepremature. Such a role eventually fell to theUnited States Public Health Service after agradual evolution .Under the Ad for the Relief of Sick andDisabled Seamen passed in 1798, a chain ofmarine hospitals at inland and coastal portsgradually emerged under the loose directionof the Treasury Department. In 1871 theDepartment brought them under thecentralized control of a Supervising Surgeon ,later renamed the Surgeon General. TheMar i ne Hospital Service thus createdgradually took over quarantineadministration, the control of vaccines,epidemiological investigation, and otherhealth-related functions . By 1912 the agency 'sgrowing scope was reflected in its presentname, the Public Health Service. During the1930s the Hygienic Laboratory, an outgrowthof bacteriological studies conducted duringthe mid-1880s by joseph ). Kinyoun at theMarine Hospital on Staten Island, became theNational Institute of Health , located atBethesda, Maryland .

Supplementing governmental efforts,laymen and physicians have organized topromote research, education, legislation, andimproved methods. The American PublicHealth Association and other professionalsocieties were established in the 1870s andlater. The Pennsylvania Society for thePrevention of Tuberculosis, established in1892, provided the model for other voluntaryassociations aimed at this and other specifichealth problems . Similarly, wealthyindividuals have supported public healththrough the Russell Sage, Kellogg, Milbankand other foundations. The RockefellerSanitary Commission carried out a far reaching anti-hookworm campaign in theSouth from 1909-1914. The RockefellerFoundation has supported sanitary work inforeign countries and financed the firstAmerican schools of public health.

Another area of public health concern forat least 150 years has been the improvementand expansion of vital statistics. Even beforethe Civil War, the American MedicalAssociation and others promoted stateregistration and the federal census begancollecting vital statistics. Followingimprovements introduced by John ShawBillings in 1880 and 1890, a permanent CensusBureau was created in 1902.As mid-19th century statistics showed thecorrelation of high mortality rates with filthyconditions , the specialty of sanitaryengineering emerged after the Civil War tohelp provide adequate sewer and watersystems, . and to organize urban streetcleaning and garbage removal. George E.Waring , a pioneer in this field , dramatizedpublic sanitation by putting New York 's streetcleaners into white uniforms, thus earningthem the sobriquet of " white wings. "After 1880 bacteriology transformed publichealth activity. Particularly important pioneerapplications were made by scientists of theArmy and the Department of Agriculture andby health officials in Rhode Island, Michigan,and New York. Scientific Bulletin No . 1 of theNew York City bacteriological laboratorymarked the beginning of laboratory diagnosisas a routine procedure in the control ofinfectious diseases.Preventive medicine goes back to theintroduction of smallpox i nnoculation byCotton Mather and Zabdiel Boylston inBoston in 1721 . After 1800 it was replaced bythe more effective and less dangerousJennerian vaccination . With the developmentof bacteriology, European discoveries such asPa steur 's rabie s treatment, diphtheriaantitoxin, and typhoid vaccination werequickly introduced into the United States .Thereafter, progress in immunology was

slow; by World War II it was overshadowed bynew drugs, especially penicillin. Theintroduction of polio vaccine in the 1950s,following a massive research effort, was thus athrilling publ ic and scientific event. Recentdecades have also seen important progress inimmunization against influenza, measles,allergies, and other diseases.Other public health specialties have alsodeveloped. Although Benjamin M 'Creadyhad made a general survey of the healthfactors in different American occupations asearly as 1837, Alice Hamilton still felt in 1910that she was entering industrial medicine " asa pioneer into a new, unexplored field. "Dental public healt h has also come of age, itsmost notable achievement, albeit a highlycontroversial one in some communities,being the fluoridation of public watersupplies to reduce dental caries.Alice Hamilton (1869-1970)Photo of the National Institutes ofHealth in Bethesda, Maryland, 1949.

Scientific ContributionsChanges in medical education and the growth of medical literature formed essential institutionalbases for the increasing number of contributions to knowledge by American physicians, scientists,and other health professionals and for their increasing ability to care for their patients. A few havebeen selected by way of illustration ; many others are equally deserving.-J. Marion Simms (1813-1883), for contributions to gynecology.-William T. G. Morton (1819-1868), for surgical anesthesia.-S. Weir Mitchell (1829-1914) , for work in cl inical neurology.-Joseph Leidy (1823-1891), for contributions to paleontology.-Abraham Jacobi (1830-1919) , for establishing pediatrics as a specialty.-Joseph J. Woodward (1833-1884), for contributions to microscopy and photomicrography.-Mary Adelaide Nutting (1858-1948) , for rai sing the standards of nursing.-Harvey W . Wiley (1844-1930) , for his campaigns against food adulteration.-William H. Welch (1850-1934) , for his major role iri introducing scientific medicine to the U.S.-John J. Abel (1857-1938) , for the isolation of epinephrine and early studies in plasmapheresis.-Theobold H. Smith (1859-1934) , for demonstrating the tick transmission ofTexas cattle fever.-Walter Reed (1851-1902) , for studies on yellow fever.-Thomas Hunt Morgan (1866-1945), for the chromosome theory.-Charles Wardell Stiles (1867-1941) , for solving the problem of hookworm disease.-Alice Hamilton (1869-1970), for work in industrial medicine.-Walter B. Cannon (1871 -1945), for studies of the autonomic nervous system .-Eugene L. Opie (1873-1971) , for contributions to the pathology of diabetes mellitus andtu bercu los is.-Florence R. Sabin (1871-1953) , for research in neuroanatomy and embryology.-Joseph Goldberger (1874-1929), for demonstrating the role of dietary deficiency in pellagra.-Oswald T. Avery (1877-1955), for work with the transforming factor in pneumococci-DNA.

Michael M . Davis (1879-1971) , for efforts to improve health care delivery.Donald D. VanSlyke (1883-1971) , for studies on acid-base balance and the gas and eledrolyteequilibria in the blood .Paul R. Hawley (1891-1964) and Paul B. Magnuson (1884-1968) , for improving medical care forveterans.-Richard H. Shryock (1893-1927), for studies in the social history of medicine.Alfred Blalock (1899-1964) , for work on shock and contributions to cardiac surgery.Percy L. Julian (1899-1975), for work in steroid chemistry.Charles R. Drew (1904-1950) , for studies on blood plasma and blood preservation.John H. Gibbon (1904-1973) , for developing the heart-lung machine.Silas Weir Mitchell(1829-1914), shownin his clinic at theInfirmary for NervousDisease in Philadelphia.Mary Adelaide Nutting(1858-1948), leadingfigure in U.S. nursingeducation.Joseph Goldberger(1874-1929), member ofthe U.S. Public HealthService who conductedinnovative experimentsin the study of pellagra.Charles R. Drew (1904 1950), leadingresearcher in the studyof blood plasma andblood preservation.

National LibraryDuring the past century of outstandingprogress in medicine and public health , theNational Library of Medicine has continuedto play an important role in making newknowledge more readily available .The Library has descended from a smallcollection of books begun by SurgeonGeneral Joseph Lovell about 1818. As theyears passed, it grew slowly ; in 1840 a clerkwrote the titles- about 200 altogether- in alittle notebook that he titled grandly, " Acatalogue of books in the library of theSurgeon General's Office, Washington City."The collection continued to expand at amodest pace until 1871 , when the decisionwas made to develop it into the " NationalMedical Library." This, to the SurgeonGeneral and h is staff, meant a collection thatcontained every medical book published inthe United States, and as many as possible ofall other publications relating to medicineand allied sciences. Assistant Surgeon JohnShaw Billings was given the responsibility forcarrying out this decision .Billings, who had been managing thelibrary since 1865, greatly accelerated thecollecting of all medical publications. Hesought new and old books, Amer ican andforeign periodicals, reports of civilian andmilitary health organizations, dissertations,pa mphlets, manuscripts, portra its and prints.He purcha sed from booksellers andphysic ian s, e xchanged duplicates withindividuals and with other libraries, andpersuaded physicians, institutions, editors,and publishers to donate publications. With ina few years Billings had acquired practicallyevery issue of every medical journal everpublished in the United States and Canada,and 75 per cent of all medical periodicals everpublished throughout the world. By 1875 thelibrary was already more than twice as large asthe next largest American medical library.With this resource at his command, Billingsconceived and established medicalbibliographies of importance to physiciansthroughout the world. In 1879 he founded themonthly Index Medicus, publishedcommercially under the ed itorship of hiscolleague Robert Fletcher. In 1880 he broughtout the first volume of the Index-Catalogue ofthe Library of the Surgeon-General's Office , amonumental work that made the Libraryinternationally famous. For three-quarters ofa century volumes continued to appear , 61 inall , until it was superseded by more rapidindexes in the 1960s.After Billings retired in 1895, the librarian 'sjohn Shaw Billings (1838-1913)Surgeon General joseph Lovell (1788 1836)

of Medicinechair was occupied by a succession of medicalofficers, among them Walter Reed. TheLibrary building on the Mall, opened in 1887,soon became gorged with material. Within 25years librarians were asking for more space,but wars , depressions, and priorities kept theLibrary in its increasingly obsolescentstructure. Finally, in 1956 Congress passed alaw formally establishing the Library as theNational Library of Medicine, transferring itto the Public Health Service, and providingfor a new building. In 1962 the Library movedfrom Washington to its new home adjacent tothe National Institutes of Health.Because of the great increase in medicalpublication starting in the late 1940s and thedemands for faster bibliographic service, theLibrary turned to new technologies in the1950s to speed the availability of indexes andthe transmission of data to users. A partiallymechanized publications system wasintroduced in 1960 to produce IndexMedicus, only to be superseded four yearslater by a computerized system namedLibrary building on the mall, opened in1887.Reading room, Army MedicalLibrary. Dr. Billings is shownseated at right (ca 1890).

MEDLARS (MEDical Literature Analysis andRetrieval System) . In the 1970s, usingMEDLARS and other data bases, the Librarydeveloped MEDLINE and a number of othernationwide on-line bibliographic retrievalsystems. To speed service to medicalresearchers, educators, and practitioners, theLibrary provided leadership and funding forthe development of a network of regionalmedical libraries. Congress gave the Libraryauthority to bestow grants-in-aid andestablished the Lister Hill National Center forBiomedical Communications to applyadvanced technology to the dissemination ·ofmedical information.A century and a half after its birth theLibrary has grown from a few books on theshelf of room in Washington to a collectionof more than a million publications, thelargest medical library in the world , operatingone of the world 's largest bibliographicinformation retrieval systems. Its services areknown and used throughout the world.Below: The National Library ofMedicine's present building, completedin 1962.Right: MEDLINE terminal. MEDLINE(MEDLAR5-0n-Line) is the library'scomputerized data base.

Images of theAmerican PhysicianPictures of physicians, other than formalportraits, have tended to fall into one of twogroups: the kindly "family doctor," or thecaricature.The "family doctor" concept is usuallyvisualized as a one-to-one relationship in asimple setting between a compassionatedoctor and a worried but hopeful patient,often with family. It has been repeatedlyimpressed on the American consciousness bymagazine art, such as that of the skillfulillustrator Norman Rockwell, by advertising,and by movies.Caricature, on the other hand, hastraditionally lampooned not only medicalmen but also quacks and patients. In America,medical caricature has been largely confinedto magazine and newspaper cartoons.Recently it has been appearing in fine printsby contemporary American artists and seemsto express a growing concern with perceiveddepersonalization and increasing costs ofmedical care. As America moves into its thirdcentury, these views of sensitive observersreflect some of the serious social problemsfacing medicine in the years ahead.Children's Clinic, by Mabel DwightVirgil Partch's contemplative doctor.

DHEW Publication No. (NIH) 76-1069

The first American medical journal, The Medical Respository, was started in New York in 1797. In the half century following, the number gradually grew. Monographs also appeared in increasing profusion, although