Transcription

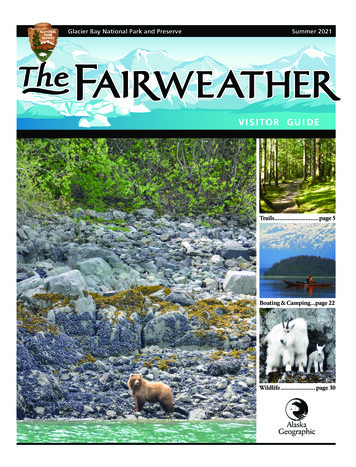

Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve Summer 2021V I S I TOR G U I D ETrails page 5Boating & Camping.page 22Wildlife page 30

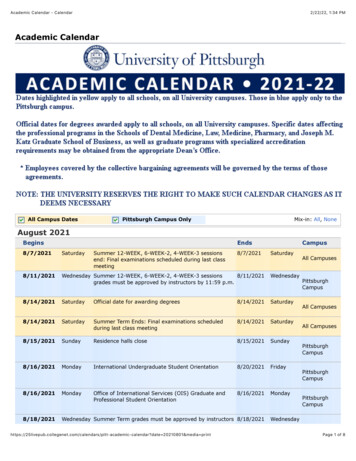

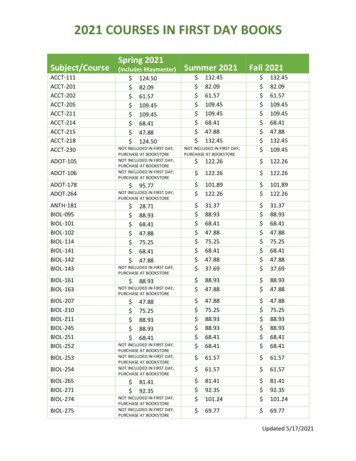

Table of ContentsGeneral Information 3–13Explore Glacier Bay highlightsPark Science 14–19Discover stories behind the sceneryGuide to Park Waters Map 20–21Traveling, Boating & Camping 22–29Plan your adventureWildlife 30–36Look, listen, and protectFor Teachers 37Share Glacier Bay with your classFor Kids 38Become a Junior RangerStay Connected 39Support your parkAdditional Information. . . . back coverEmergency, Medical, and Contact UsThe FairweatherProduced by:Designed by: National Park Service and Alaska GeographicPark Coordinator: Laura BuchheitEditor: Matthew EnderleGraphics: Sean TevebaughWelcome to Glacier BayWelcome to Glacier BayNational Park and Preserve,a place defined by beautyand hope, change andresilience. These are familiarconcepts reflected in thechallenges we face with thepandemic and our sharedefforts to protect what wetreasure.If you are here this summer, then you successfullynavigated the gauntlet of new requirements,restrictions, and fears of travel. You might even havea better appreciation for the challenges faced by thosein the past who came to visit this special place.By now, we had all hoped that we might be furtheralong in our ability to freely visit our National Parks.We also feared that finding a vaccine and a path outof the pandemic might take much longer. Instead,we now find ourselves in the middle place. Alaska’scommunities and travel industry are excited tostart to welcome people back, but the lack of herdimmunity requires us to be cautious and many remotecommunities here are justifiably concerned. Luckily,many of the best experiences in Glacier Bay – suchas breathing in the quiet beauty rather than the airof a crowd – are found outside and can be enjoyedresponsibly so our most vulnerable are protected.Parks are about shared ownership, working togetheras a nation and world to care for a treasure we wantto pass on to our children. Successfully dealing withthe pandemic requires much of the same: collectiveaction to preserve what is precious. Collaboration isespecially important for our vulnerable populations:the tribal elders who hold so much of Tlingit culture,or the people who worked so hard to create thecommunities and protect the areas you are visitingand who still live here. Please join us in helping tokeep this special place special and to ensure the safetyand well-being of yourselves, your fellow travelers,and our local communities.There is a memorial coin beneath each of the fourhouse posts in Xunaa Shuka Hit (page 6), the Eagleand Raven poles outside, and the Healing totem (page8). These coins have a statement, engraved in Tlingitand English, that drive every decision and everyaction this park takes:Haa yátx’i jeeyís áyáFor Our Children Forever.Philip Hooge,SuperintendentEnjoying these places requires flexibility in thoughtand action. You may find your mid-summer tripoccurring when many restrictions have been relaxedand local and regional COVID-19 cases are very low,or you may find yourself in a time of rising numbersand tightening restrictions.Contributors: Michael Bower, Laura Buchheit, Brian Buma, KatConnelly, Sara Doyle, Lisa Etherington, Chris Gabriele, MargaretHazen, Philip Hooge, Emma Johnson, Tania Lewis, Dan Mann,Sandy Milner, Mary Beth Moss, Janet Neilson, Steven Schaller,Melissa Senac, Lewis Sharman, Scott Gende, Ingrid Nixon, andDarlene See.Special thanks to the following photographers:Kaytie Boomer, Michael Bower, Brian Buma, Sara Doyle, JaneneDriscoll (inside cover), Chris Gabriele, Tania Lewis, Dan Mann,Craig Murdoch (front cover), Janet Neilson, Sean Neilson, SteveSchaller, Sean Tevebaugh, and NPS seasonal staff.The Fairweather is published by Alaska Geographic Associationand Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve.Printed on recycled paper using soy-based inks. Alaska GeographicVisitors to Bartlett Cove can still experience the wild, glaciallandscape of Glacier Bay.Glacier Bay offers a myriad of opportunities to “Find Your Park.”3

Explore Bartlett CoveTrailsBartlett Cove is the only developed area withinthe wilds of Glacier Bay. The forests andshorelines offer great opportunities for hikingand exploring. Maps are available at Glacier BayLodge and the Visitor Information Station (VIS).Forest TrailDistance: 0.7 miles (1.1 km) one wayTime: 30 minutes–1.5 hoursThis leisurely stroll meanders through a lushforest that grows atop a glacial moraine. Awheelchair accessible boardwalk takes you partof the way, leading to two viewing decks thatoverlook a serene pond. Return along the shorefor an easy one-mile loop.The shores of Barlett Cove offer opportunities to explore.If you just have a few hours.If you have a half day.Stop by the Visitor Center: On the second floor of theGlacier Bay Lodge is the National Park Service (NPS)information desk and exhibits. Open daily when lodgeis open. Educational materials and souvenirs availablefor purchase from Alaska Geographic.Hike to the Bartlett River: See trail details, page 5.Walk the Forest Trail: See trail details, page 5.If you have a full day.Go for a beach walk: See trail details, page 5.Explore the intertidal zone at low tide: See mappage 5.Hike to Bartlett Lake: See trail details, page 5.Join a Ranger Program: See bulletin boards or parkwebsite for schedule of activities happening duringyour visit.Go for a paddle: There are several options for kayakingaround Bartlett Cove. Take a guided kayak trip, or rentyour own from Glacier Bay Sea Kayaks.Visit the Whale Exhibit: See one of the largesthumpback whale skeletons on display in the world.Located near the Visitor Information Station.Become a Junior Ranger: Kids can pick up their freeJunior Ranger Activity Book from the NPS informationdesk at the Glacier Bay Lodge, or from the VisitorInformation Station (VIS). See page 38.View the Tribal House and the Healing Pole:Walk along the Tlingit Trail to explore Huna Tlingitconnections to Glacier Bay. See pages 6–8.Explore Glacier Bay on the Dayboat: Spend the dayexploring Glacier Bay to observe wildlife and tidewaterglaciers. Stop by the lodge for availability*.Get the Latest Schedule of EventsPlease see the NPS VisitorCenter information desk in the Glacier BayLodge, the bulletin board in front of thelodge, or the Visitor Information Station(VIS) near the public dock for updates andinformation on available services.4Tlingit TrailDistance: 0.5 mile (800 m) one wayTime: 30 minutes–1 hourEnjoy this easy stroll along a forested shoreline.View the Healing Pole and a traditional Tlingitcanoe, admire a complete whale skeleton, learnabout common native plants, and take in theRaven and Eagle totems, as well as the exterior ofthe Tribal House.Bartlett River TrailDistance: 4 miles (6.4 km) round tripTime: 4–5 hoursExplore a dense spruce-hemlock rainforest. Thetrail through the forest ends at an estuary nearthe mouth of the river. Each summer, spawningsalmon attract otters, eagles, seals, and bears.Anglers enjoy fishing there, too.Bartlett Lake TrailDistance: 8 miles (16 km) round tripTime: 7–8 hoursAbout ¾ of a mile down the Bartlett River Trailyou will find the lake trail, a branch trail thatclimbs the moraine. This primitive trail is arugged day-hike, with rewards of solitude and atranquil lake. Bring water, food, and rain gear.Explore the ShoreDistance: variesThe shoreline beyond the docks continues formiles past the campground. You may observeland and marine wildlife. Look for birds, listenfor whales, and watch for sea otters feeding nearshore. This is not a maintained trail.5

Xunaa Shuká HítXunaa Shuká Hít stands proudly on the shores of Bartlett Cove.Dressed in the beaded vest of a Tlingit elder, tribalinterpreter Don Starbard shares with visitors: “There’sa good balance now. Yes, our young people are goingoff to college to become successful. But our languageis strong. Our dance is strong. Our canoe culture isstrong, and, most importantly, our connection toHomeland remains strong.” All summer long, visitorsgather at the Tribal House. They listen to traditionalstories and explore the intricately carved and paintedbuilding. Cultural interpreters working for the NationalPark Service (NPS) and the Hoonah Indian Association(HIA), the tribal government, share deeply of theirtraditions, history, enduring connection to Glacier Bayhomeland, and the collaborative efforts that led to thecompletion of this magnificent building.throughout Glacier Bay prior to the Little Ice Age.Although villages inside the bay were overrun byglacial advances in the 1700s, the Huna Tlingit reestablished fish camps and seasonal villages soonafter glacial retreat. Establishment of Glacier BayNational Monument in 1925 (and later National Park)and implementation of laws and park regulations ledto a period of alienation and strained relationshipsbetween tribal people and the NPS. Time and newunderstandings have brought much healing. In recentyears, the NPS and HIA worked cooperatively toreinvigorate traditional activities, develop culturalprograms for youth and adults, amend regulations toallow for a broader range of traditional harvests in parkboundaries, and preserve oral histories.For countless generations, the Huna Tlingit sustainedthemselves on the abundant resources foundThe most symbolic cooperative venture—Xunaa ShukáHít (roughly translated as Huna Ancestors’ House)—HIA cultural interpreter leads a group down the Tlingit Trail toXunaa Shuká Hít.6Hoonah youth welcome traditional dugout canoes on BartlettCove’s shoreline during the 2018 Healing Pole Dedication.Tribal members dance and sing during the August 2016 TribalHouse Dedication.NPS cultural interpreter shares messages represented within theRaven and Eagle totems.now stands proudly on the shoreline of Bartlett Cove.Dedicated in August 2016 and opened to the public insummer 2017, it now draws thousands of visitors fromaround the world.sides of Xunaa Shuká Hít. In August 2018, these poleswere joined by Yaa Naa Néx Kootéeyaa (Healing Pole).This totem, collaboratively designed by NPS and HIA,reveals the story of the journey through a painful pastto a healthier, more meaningful partnership. XunaaShuká Hít is a place of learning, growth, inspiration,and continued healing for generations to come.A team of clan leaders, craftsmen, planners, architects,and cultural resource specialists designed XunaaShuká Hít to reflect a traditional architectural stylereminiscent of ancestral clan houses with moderntouches suitable for the needs of the community today.Inside the Tribal House are four richly detailed massivecedar interior house posts and an interior house screenwhich depicts the stories of the four primary HunaTlingit clans and their tie to Glacier Bay homeland.These cultural elements impart spiritual value to theTribal House, and, as importantly, their design andcompletion expand the circle of tribal members whohold traditional skills and share in cultural knowledge.The 2,500 square foot Tribal House is not only a placefor visitors to learn about Tlingit traditions, but isalso a venue for tribal members to reconnect withtheir traditional homeland, life-ways, and ancestralknowledge. Within months of its dedication, the TribalHouse inspired native high school students to spendtheir winter school break at the Tribal House learningtraditional crafts from elders and culture bearers.Months later, hundreds of tribal members gatheredto raise the Eagle and Raven totems that grace theImages of the Huna Tribal House dedication andcarving projects are available on the park’s websiteunder the Tribal House Media Gallery. To learn moreabout special events and opportunities to experiencethe Tribal House, check the posted activity schedules inBartlett Cove or ask a ranger.Traditional songs inspire the strength and stamina to carry theRaven and Eagle totems at the May 2017 Totem Raising.7

Planning for our ParkYaa Naa Néx KootéeyaaI believe we are on a path - that our people will be remembered.”- Frank Wright Jr, President of Hoonah Indian AssociationOur pole.is a story pole. It is, essentially,the recorded history, not only of the HunaTlingit, not only of Glacier Bay NationalPark, but of our long, sometimes painful,sometimes joyous, journey together.- Philip Hooge, SuperintendentJourney of HealingPhilip Hooge (left) and FrankWright, Jr. (right) at the Healing PoleDedication.The National Park Service caresfor special places saved by theRaised on August 25, 2018, Yaa Naa Néx Kootéeyaa (Healing Pole) tellsthe story of the long journey for both Huna Tlingit and the NationalPark Service to heal years of misunderstandings and hurt.Designed collaboratively by tribal elders, carvers, and NPS staff,the pole contains a mix of traditional formline design and modernrepresentations of symbols—differentiating it from other poles inSoutheast Alaska.Glacier Bay is the traditionalhome and “breadbasket” of theHuna Tlingit—sustaining themphysically and spiritually until arapidly advancing glacier pushedthem out in the late 1700s.The Huna Tlingit felt that thefederal government—a faceless,soulless being with too manyhands—barred them from manytraditional practices upon theirreturn after the glacier receded.Traditional dugout canoessupport healing journeyscooperatively planned byNPS and the Hoonah IndianAssociation—connecting tribalmembers with Glacier Bayhomeland.Visit the Healing Pole next to the Visitor Information Station,and read the complete story from bottom to top at our website:go.NPS.gov/healingtotem8American people so that all mayexperience our heritage.Glacier Bay by satellite, from NASA’s Earth Observatory.Your Opinion CountsYou are a part of a long legacy of adventurers inspired byGlacier Bay! Keep connected and involved even from afar.The NPS relies on your feedback to help guide stewardshipof America’s great natural and cultural resources.Glacier Bay National Park is currently working with theNPS to update some of the park’s management plans. Thisplanning effort will strengthen the park service missionto provide for visitor enjoyment while also preserving thepark’s extraordinary natural and cultural heritage forfuture generations.Please take the time to visit our Frontcountry andBackcountry Management Plan websites (see below) orcontact us (see right) to learn more about our process andprogress, and to offer your unique perspective. There aremultiple ways you can be involved.Follow implementation of theupdated Bartlett Cove plan:go.nps.gov/GLBA FMPFrontcountry ManagementPlan websiteFollow Glacier Bay wildernessexperience planning:go.nps.gov/GBwildBackcountry ManagementPlan websiteStay Tuned!You don’t need to live close by to be connectedand stay involved. You can follow progress andoffer feedback to inform park planning in thefollowing ways: SUBSCRIBE to our planning notification listby sending us your contact information:glba public comments@nps.govGlacier Bay National Park & PreservePO Box 140Gustavus AK 99826 FOLLOW the park’s social media for pressreleases and planning announcements (publicmeetings, review drafts, comment periods). VISIT US ONLINE to learn more aboutpark management: isit the NPS online portal for real time public notices and commentopportunities: Planning, Environment, and Public Comment (PEPC)https://parkplanning.nps.gov/glba9

Timeline of Glacier Bay1980 Congress, under1794Since time immemorial,Tlingit clans live in the area thatis now Glacier Bay. Advancingglaciers in the 1700s during theLittle Ice Age force the Tlingitout of their homeland. Afterthe Little Ice Age, the glaciermelts back and the ocean fillsthe valley quickly, creatingGlacier Bay.17501770s–1790sEuropean explorers arrive.Excursions led by CaptainsMalaspina, La Perouse, Cook,Vancouver, and many othersprovide the first westerndescriptions of the area and itspeople. Cartographers createthe first maps of the area andnon-Native names are given tolandforms.10Captain GeorgeVancouver of the H.M.S.Discovery and Lt. JosephWhidbey describe GlacierBay as “a compact sheet ofice as far as the eye coulddistinguish.” The “bay” is amere five-mile indentationin the coastline.18001925 Ecologist William1883 James Carroll and othercommercial steamship captainsmake Muir Glacier a populartourist destination.18501900Park Service and HoonahIndian Associationsign a Memorandum ofUnderstanding to establisha working partnership.19501916U.S. Congress passesthe Organic Act, creating theNational Park Service.part of the “Mission 66” initiativethat brought facility improvementsto national parks nationwide duringthe 50th anniversary of the NationalPark Service.2020 Reducedpark operationscontinue withlimited visitationdue to the Covid-19pandemic. In2019, Glacier Baywelcomes over640,000 visitors.200020161966 Glacier Bay Lodge opens as1879 John Muir, guided by Tlingitmen, paddles into Glacier Bay. Theyfind the glacial ice has retreated 40miles since 1794. Muir returns threetimes over the next 15 years. Heconstructs a cabin, makes extensiveobservations of glaciers, andexplains interglacial tree stumps.The eloquent writings of enthusiastslike Muir and Eliza Scidmore beginattracting new visitors to the bay.S. Cooper, studying plantsuccession in Glacier Bay,and the Ecological Societyof America persuadePresident Coolidge toestablish Glacier BayNational Monument.the leadership of PresidentJimmy Carter, signs theAlaska National InterestLands Conservation Actinto law. Glacier Baybecomes a national parkand preserve encompassing3.3 million acres.1995 The National1992 UNESCO designatesGlacier Bay, along withWrangell-St. Elias National Parkand Preserve (Alaska), KluaneNational Park Reserve (Canada)and Tatshenshini-AlsekProvincial Park (Canada), as a24-million-acre World HeritageSite, one of the world’s largestinternationally protected areas.The NationalPark Service celebratesits centennial: 100 yearsof “America’s Best Idea.”Glacier Bay celebrateswith the opening of theHuna Tribal House, acollaborative projectwith the Hoonah IndianAssociation. The buildingserves as a cultural anchorand a place of learning.11

World HeritageGlaciersA cruise ship appears small within the expansive Glacier Bay landscape. Through careful vessel management, Glacier Bay NationalPark seeks to balance visitation with resource preservation.International ConnectionsA cruise ship sails into Glacier Bay, one of potentially onlytwo for that summer’s day. The ship’s company followsvoluntary environmental protocols to reduce vesselemissions and lower impacts. The ship’s crew curtailsactivities aboard, encouraging passengers to take in thewilderness around them. Interpretive rangers, invitedaboard for the day, share stories of the park and itssignificance. After visiting the tidewater glaciers, the shipeventually departs leaving nothing but its wake.the 50 marine sites on the United Nations Educational,Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO)converged on Bartlett Cove for a symposium withone major goal: to learn from each other how to bestmanage their protected areas. Over the five-day event,managers from sites all over the world shared stories ofthe challenges they face including increasing visitation,climate change, and marine pollution. They also sharedsolutions.This Glacier Bay model of vessel management is asignificant reason why in September 2019, managers ofAccording to Superintendent Philip Hooge, thegathering was a chance to highlight the park’ssuccess with public-private partnerships. “Workingtogether with the cruise industry we have been ableto successfully deal with some of the issues associatedwith cruise tourism,” he said, “and achieve higherenvironmental standards using means other than theregulatory process.”Park Superintendent and West Norwegian Fjords BoardChairman sign Sister Park Agreement at Lamplugh Glacier.12While in the bay in front of the Lamplugh Glacier withthe marine managers cheering on, SuperintendentHooge signed a Sister Park Agreement withrepresentatives of West Norwegian Fjords WorldHeritage Site in Norway. The two sites have much incommon in that they both feature scenic fjords withmajor visitation by cruise ships. “This provides anincredible opportunity for protected areas that share somuch to learn from each other,” said Hooge.A glacier flows from the Fairweather Mountains. Glaciers continue to change in response to their environment.Rivers of IceTall, coastal mountains and an abundance of snowmake Glacier Bay a comfortable home for hundreds ofglaciers. Storms from the Pacific Ocean collide with thetowering Fairweather Mountains, often producing rainat sea level and snow at higher elevations. More snowfalls each year than melts in the mountains. The snowcompacts, forming ice. With the influence of gravity,the ice slides down the mountainside. Basically, ice inmotion is a glacier.As a glacier flows down the mountainside, it reacheswarmer elevations. When the air above a glacier is abovefreezing or if it is raining, then ice melts. The balancebetween the amount of ice forming and ice meltingdetermines whether a glacier advances (grows) orretreats (shrinks), though it always flows forward.Glaciers shrink in size when more ice is lost from melting thangained from snowfall.“Words and dry figures can give one little ideaof the grandeur of this glacial torrent flowingsteadily and solidly into the sea, and the beautyof the fantastic ice front, shimmering with all theprismatic hues, beyond imagery or description.”-Eliza Scidmore, 1883A few glaciers, called tidewater glaciers, reach all theway to the ocean and are strong enough to survivewith their ice touching warm ocean water. Tidewaterglaciers have a naturally occurring cycle of advanceand retreat that has shaped Glacier Bay for millennia. Afew hundred years ago, a glacier that sat mid-way downthe bay for centuries advanced rapidly until it came tothe waters of Icy Strait. The salty ocean water causedthe glacial ice to melt and dramatically break away ina process called calving. Snowfall couldn’t keep upwith the amount of melting and calving, so the glacierretreated quickly. All of the glaciers visitors see in thepark today are remnants of that once large glacier.Changes to glacial ice continue in Glacier Bay. Whiletidewater glaciers are still influenced by ocean water,all glaciers are now impacted by a rapidly warmingplanet. Glacier Bay National Park will continue to studyglaciers as the climate warms. As a living labratory,Glacier Bay provides outstanding opportunities toexplore the intricate dynamics of glaciers.13

Park ScienceVisitors and researchers alike from around the worldexplore and admire Glacier Bay. The dramatic retreatof glaciers created a premiere scientific laboratory.Explorer John Muir initiated the park’s remarkablelegacy of scientific inquiry in the late 1800s. BotanistWilliam Cooper secured protected status for GlacierBay following his research about how plant lifefollows glacial retreat. In fact, the initial proclamationprotecting Glacier Bay National Park states researchas a reason for national preservation. From whales andplankton to climate and otters, research is a commonoccurrence in the protected laboratory of Glacier Bay.This scientific study provides greater understandingand appreciation for the wilderness we explore. Learnmore by reading the following pages, and make yourown discoveries in Glacier Bay.“The most beautiful thing we can experienceis the mysterious. It is the source of all true artand science.”- Albert EinsteinWilliam S. Cooper recognized Glacier Bay as a living laboratory. He studied the process of pioneer plants colonizing land recentlyrevealed by retreating glaciers.Meet a researcherSandy Milner, Pioneer of Glacier Bay StreamsDr. Milner has studiedstreams created after glacierretreat for 40 years.Dr. Alexander “Sandy”Milner has been researchingGlacier Bay’s streams for38 of the past 40 summers!His first visit was as anundergraduate student onan expedition from ChelseaCollege, UK in 1977. Herehe found a natural livinglaboratory, a place topioneer research on how lifeestablishes in new streams.Today, Dr. Milner is regarded as the world experton stream ecosystem development following glacialretreat. His work has revealed the patterns of streamsuccession as new watersheds form in this dynamiclandscape. As streams age, the stream channelsstabilize, water clarity improves, and water temperatureThe mouth of Wolf Point Creek (pictured 40 years ago) emergedfrom under the retreating glacier in the mid 1940s.14increases. Aquatic insect fauna become more diverseand abundant. Salmon colonize new spawning habitat.Dr. Milner has shared his passion for learning and forGlacier Bay as a professor at the University of Alaskaand the University of Birmingham (UK). He hassupervised 12 graduate students (ten of them Ph.D.’s)and authored 26 scientific journal articles focused onstream development in Glacier Bay.The transformation of streams continues to captivateDr. Milner. When asked why he returns to GlacierBay, he explained “I would never have thought when Isampled a cold Wolf Point Creek [Muir Inlet] with novegetation on a barren landscape in the late 1970s asit emerged from the ice, that I would still be samplingthe same stream 38 years later in a cottonwood forestwith so much biodiversity and thousands of salmonspawning. The stream system is still dynamic and everyyear a new discovery is evident.”The stream now supports pink salmon runs of more than12,000 fish.A Vision of PreservationPeople visit Glacier Bay to view amazing scenery,dramatic glaciers, and spectacular wildlife. Yet acentury ago one man saw something else of great valuehere: incredible opportunities for science.monument. One of the monument’s fundamentalmandates was to preserve the opportunity to conductscientific studies, making Glacier Bay a true “park forscience.”Botanist William Skinner Cooper (1884–1978) cameto Glacier Bay in 1916 to study how plants colonizenewly-exposed ground following glacial retreat. Herecognized Glacier Bay as the best place on earth towitness the process of “plant succession,” a fascinatinginterplay of plants, nutrients, soil, and time. In thisprocess the bare ground emerging from beneath aglacier goes through various stages to become a rich,thick, mossy evergreen forest of towering spruces andhemlocks.Dr. Cooper returned to his beloved Glacier Bay manytimes to document the successional development in thestudy areas and plots he established on his first visit.Dr. Cooper’s students and other scientists continue hiswork on how ecosystems respond to glacial recessionand, more broadly, global climate change. This ongoingresearch makes Glacier Bay the oldest continuouslyresearched post-glacial landscape in the world.Dr. Cooper saw a natural laboratory in Glacier Baywhere scientific principles could be discovered aswell as tested; a place where completely new scientificquestions could be asked. As a prominent memberof the Ecological Society of America, Dr. Coopersuccessfully led a committee of colleagues in a vigorouscampaign to lobby President Calvin Coolidge forprotection of the Glacier Bay area in 1925 as a nationalGlacier Bay is preservedas public land for manyreasons: protection ofwildlife habitat, scenery,value to the world,enjoyment by presentand future generations,and as a living laboratory.Glacier Bay still inspiresnew discoveries today.Ecologist Brian Buma continuesthe legacy of research onDr. Cooper’s original plots.From rock to rainforest—in just 75 years! Images taken at the same location document the landscape changes.15

Park ScienceNinety-five percent of Alaska’s glaciers are thinning, stagnating, or retreating.The Ice Is MeltingThe Earth’s climate is changing—and fast! InGlacier Bay, glaciers are rapidly shrinking and oceantemperature is rising. Scientists who study the Earth’sclimate have documented warming temperatures inAlaska due to increased carbon dioxide levels. Warmingtemperatures lead to changes in fire cycles, tree growth,animal migrations, and rapidly melting glaciers.Ninety-five percent of Alaska’s glaciers are currentlyretreating, thinning, or stagnating. Importantly, therate of thinning is increasing. Glacier Bay’s glaciersfollow this trend. Recent research determined thatthe area covered by ice in Glacier Bay has shrunk 15%from 1950 to now. Nevertheless, heavy snowfall in thetowering Fairweather Mountains means that a fewglaciers might remain stable in Glacier Bay, a rarity intoday’s world. Take a good look at the glaciers you see inGlacier Bay today. The next time you see these glaciers,they will be different.Alaska and other polar regions experience the effectsof climate change more strongly than other places.Decades of data from NASA’s Goddard Institute forSpace Studies show that Alaska and the polar regionshave warmed more than twice as much as the rest ofthe earth. Climate change is a reality for Alaskans,threatening villages with coastal erosion, changingsubsistence practices, and altering weather patterns.Ask park rangers about what changes they have noticedin Glacier Bay.16There is good news. Humans are inventive, resourceful,and capable of overcoming great challenges. Althoughclimate change is a global concern, we each hold a partof the answer to minimizing its impact.The Earth’s climate is changing and Glacier Bay iswarming. How will these changes affect you? Onefact is certain: the choices we make today will make adifference in the future.A weather station high above the bay collects information that will contribute to understanding Glacier Bay’s changing climate.Tracking Ecosystem

Guide to Park Waters Map 20–21 Traveling, Boating & Camping 22–29. Plan your adventure. . Alaska’s communities and travel industry are excited to start to welcome people back, but the lack of