Transcription

U N I T E D N AT I O N S C O N F E R E N C E O N T R A D E A N D D E V E L O P M E N TCOMMODITIES AT A GLANCESpecial issue on goldPhoto credit: Fotolia Roman BodnarchukN 6Layout and Printing at United Nations, Geneva – 1606266 (E) – April 2016 – 1,033 – UNCTAD/SUC/2015/3

U N I T E D N AT I O N S C O N F E R E N C E O N T R A D E A N D D E V E L O P M E N TCOMMODITIES AT A GLANCESpecial issue on goldN 6New York and Geneva 2016

iiiThe series Commodities at a Glance aims to collect, present and disseminate accurate and relevant statisticalinformation linked to international primary commodity markets in a clear, concise and reader-friendly format.This edition of Commodities at a Glance has been prepared by Alexandra Laurent, statistical assistant for theSpecial Unit on Commodities (SUC) of UNCTAD, under the overall guidance of Samuel Gayi, Head of SUC, andthe direct supervision of Janvier Nkurunziza, Chief of the Commodity Research and Analysis Section of SUC.The cover of this publication was created by Nadège Hadjemian, UNCTAD; desktop publishing and graphicswere performed by the prepress subunit with the invaluable collaboration of Nathalie Loriot of the UNOG PrintingSection.For further information about this publication, please contact the Special Unit on Commodities, UNCTAD, Palaisdes Nations, CH-1211 Geneva 10, Switzerland, tel. 41 22 917 5676, e-mail: commodities@unctad.org.EXPLANATORY NOTEAll data sources are indicated under each table and figure.Reference to dollars or use of the symbol, , signifies United States dollars, unless otherwise specified.The term “tons” refers to metric tons.Unless otherwise stated, all prices in this report are in nominal terms.DISCLAIMERThe opinions expressed in this publication are those of the author and are not to be taken as the official views ofthe UNCTAD secretariat or its member States.The designations employed and the presentation of the material do not imply the expression of any opinion onthe part of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of authorities,or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries.Material in this publication may be freely quoted or reprinted, but acknowledgment is requested, together with acopy of the publication containing the quotation or reprint, to be sent to the UNCTAD secretariat.UNCTAD/SUC/2015/3

COMMODITIES AT A GLANCE - Special issue on goldivNOTESGold can be measured in troy ounces or in kilograms. According to the World Gold Council:1 gram1 kilogram1 ton(0.032151 troy ounces)(32.1507 troy ounces)(32’150.75 troy ounces) 1 troy ounce1 troy ounce1 troy ounce(31.103 grams)(0.0311 kilograms)(0.000031 tons)GLOSSARY OF TERMSAbove-ground reserves: This source of gold reserves represents an additional category to the traditionallyagreed concept of reserves, defined as all quantities of minerals economically extractable from the ground.The term “above-ground reserves”, used mainly in the gold industry, defines all quantities of gold that havealready been mined in human history. They include all stocks of jewellery, gold held by central banks and privateinvestors, as well as all gold fabricated products.All-in sustaining costs (AISC): is a voluntary non-GAAP [Generally Accepted Accounting Principles] measureproposed by the World Gold Council to gold mining companies in 2013. This indicator covers cash costs, plusthe costs incurred by the sustainable production of mines during their complete life cycle from explorationto closure. Most of the largest gold companies now publish this indicator in their annual reports. (See WorldGold Council, Guidance note on Non-GAAP metrics – all-in sustaining costs and all-in costs. 27 June 2013, l-costs).Fineness: Defines the gold content of an alloy or impure gold. It is expressed in parts per thousand (ppm). Forexample, when a material contains 90 per cent gold and 10 per cent of another metal, it is referred to as “900 fine”.Karatage: In jewellery, when gold is alloyed with other metals, the weight of gold in the product is measured inkarats (k). Pure gold equals 24 karats.Primary production: Output from large mines, regulated gold mines (excluding informal and artisanal production).Secondary production: Mainly refers to production from recycling.

ABBREVIATIONSABBREVIATIONSAISCall-in sustaining costsASGMartisanal small-scale gold miningCBGACentral Bank Gold AgreementETFexchange-traded fundGFMSThomson Reuters GFMS SurveysICMEInternational Council on Metals and EnvironmentIMFInternational Monetary FundINRIndian rupeeKkaratKkelvinkPakilopascalm3cubic metermgmicrogrammmmicrometren.anot availableozounce(s)pgmplatinum group metalsppmparts per millionRMBChinese renminbiUAHUkrainian hryvniaUNEPUnited Nations Environment ProgrammeUSGSUnited States Geological SurveyWHOWorld Health Organizationv

viCOMMODITIES AT A GLANCE - Special issue on goldCONTENTSEXPLANATORY NOTE. iiiDISCLAIMER. iiiNOTES. ivGLOSSARY OF TERMS. ivABBREVIATIONS. vCHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION: From the gold standard to floating currencies. 11. The characteristics of gold . 32. The role of gold in economies . 33. Recent history of gold as a currency . 4a. The Gold Standard system (1870 1914). 5b. The Bretton Woods system (1944 1971). 5c. The end of the Bretton Woods system and the start of a free-floating exchangerate system (1971 to the present). 6CHAPTER 2: USES. 71. Jewellery . 92. Industrial uses . 10a. Electronics . 10b. Dentistry . 113. Gold as an investment vehicle. 11a. Physical bars and coins . 11b. ETFs and similar products. 124. National gold reserves and purchases of gold by central banks . 13a. Purchases made by central banks of emerging market economies . 14b. Reduction of gold sales by signatories to the Central Bank Gold Agreements . 15CHAPTER 3: PRODUCTION. 171. Technical aspects of gold production . 19a. Primary gold mining . 19b. The metallurgy of gold. 202. Statistics relating to gold production . 21a. Global gold production . 21b. Overview of production in the leading gold-producing countries. 23CHAPTER 4: PRICES. 311. Evolution of gold prices. 33a. Evolution of gold prices during the 1970s. 33b. Evolution of gold prices between 1980 and 2000. 33c. Evolution of gold prices since the beginning of the 2000s . 342. Gold prices and impacts on producing countries. 35

CONTENTSviiCHAPTER 5: CONCLUSIONS. 39REFERENCES. 43APPENDIX 1: THE METALLURGY OF GOLD. 49APPENDIX 2: THE STATE OF GOLD MINES AROUND THE WORLD, 2015. 55FIGURESCHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION: From the gold standard to floating currenciesFigure 1.Share of country gold reserves in total gold reserves, February 2015 (per cent).4Figure 2.Overview of the recent history of gold.5CHAPTER 2: USESFigure 3.Historical evolution of world demand for gold, and distribution of the demand by sector,2000 2014 (tons).9Figure 4.Demand for gold by jewellery sector: geographical distribution, 2014 (per cent).10Figure 5.Demand for gold by electronics sector: geographical distribution, 2014 (per cent).11Figure 6.Investments in gold bars, by weight, in China, Europe and India, 2005 2014 (tons).12Figure 7.Net ETF purchases (tons) and gold prices (dollars per troy ounce), 2005-2014.13Figure 8.Central banks of countries with the largest gold reserves, as a percentage of total worldgold reserves held by central banks, 1980 and 2014 (per cent).14Figure 9.Net purchases of gold by central banks, 1980 2014 (tons).14Figure 10. Gold sales under successive Central Bank Gold Agreements, 1999 2000 to 2013 2014 (tons).16CHAPTER 3: PRODUCTIONFigure 11. The metallurgy of gold.21Figure 12. World primary gold production, 1900 2014 (tons).22Figure 13. Shares of leading gold mine producing countries in total world mine production, 1980 and 2014(per cent) 22Figure 14a. Ten leading gold companies in terms of gold production, 2014 .23Figure 14b. Ten leading gold companies in terms of market capitalization, 5 October 2015 (billions of dollars). 23Figure 15. Large-scale gold mining versus artisanal small-scale gold mining .26Figure 16. Distribution of world gold supply between mine production and recycling, as a percentageof world gold supply (per cent) compared to international gold prices (dollars per troy ounce),2004 2014 .28CHAPTER 4: PRICESFigure 17. Historical evolution of nominal and real gold prices, 1970 2014 (dollars per troy ounce,base year: 2010).33Figure 18. How quantitative easing affects gold prices.34Figure 19a. Average monthly change in the price of gold, 1970-2014 (per cent).35Figure 19b. Seasonality of gold prices, 2000-2014 (monthly percentage change).35

viiiCOMMODITIES AT A GLANCE - Special issue on goldTABLESTable 1.Concentration of gold and other selected industrial and precious metals in the earth’s crust (ppm).3Table 2.Trends in real GDP growth and gold reserves in emerging market economies, 2000 2014(per cent and tons).15Table 3.Gold ore types.19Table 4.Five leading gold-producing mines in Australia, 2014 (troy ounces).24Table 5.Five leading gold-producing mines in the Russian Federation, 2014 (troy ounces).24Table 6.Five leading gold-producing mines in the United States, 2014 (troy ounces).25Table 7.Five leading gold-producing mines in Canada, 2014 (troy ounces).25Table 8.Five leading gold-producing mines in South Africa, 2014 (troy ounces).25Table 9.Five leading gold-producing mines in Peru, 2014 (troy ounces).26Table 10.Economic importance of gold in selected countries.27Table 11.Mineral tax on gold mine production in producing countries, as of January 2012.36

CHAPTER 4 - PRICESCHAPTER 1:INTRODUCTIONFrom the gold standard tofloating currencies1

3CHAPTER 1 - INTRODUCTION From the gold standard to floating currencies1. THE CHARACTERISTICS OF GOLDTable 1. Concentration of gold and other selected industrialand precious metals in the earth’s crust (ppm)Gold is a precious yellow, bright and highly valuedmetal. It has been known, appreciated and used forthousands of years. The first documented goldminein the world, estimated to be 4,000 years old, wasdiscovered in Tbilisi (Georgia) in 2005.AtomicnumberThe origins of gold are considered to be “cosmic”. In2013, the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysicsnoted that observations have found evidence that goldwas created in a short gamma-ray burst resulting from“the collision of two neutron stars the dead cores ofstars that previously exploded as supernovae”.1Symbol: Au (from Aurum)Atomic number: 79Density: 19.32 g/cm3Melting point: 1,064 CAtomic mass: 196.97 atomic mass units (amu)Gold is among the rarest elements in the earth’s crust(table 1), where it is mainly present in its native form(about 80 per cent of the total metal worldwide); itcan also be associated with other elements, such assilver resulting mainly in the elements, electrum andtellurium but also with copper or iron, among others.Gold is the most malleable and ductile transitionmetal, meaning that it can be shaped and bent easily.It is considered a heavy metal and one of the densestelements in the periodic table. Like silver, iridium,osmium, palladium, platinum, rhodium and ruthenium,it is a noble metal, which means that it presents anexceptional resistance to oxidation. However, goldcan be dissolved in aqua regia.2 Gold is also a goodconductor of heat and electricity, and a strong reflectorof infrared radiation. Based on these characteristics, itis used as input in many industries, such as jewellery,dentistry or electronics, and for electrical applications.However, its softness and high prices ( 1,428 per troyounce, on average, between 2010 and 2014) tend tolimit its use to sectors where no efficient substituteshave been developed, or encourage its mixture with12Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, Earth’sgold came from colliding dead stars, 17 July 2013 cribed by Oxford Dictionaries online as “A mixture ofconcentrated nitric and hydrochloric acids. It is a highlycorrosive liquid able to attack gold and other resistantsubstances”.NameCrustSymbol abundance(ppm)Group13AluminiumAl79 000Industrial metal26IronFe55 350Industrial metal12MagnesiumMg26 000Industrial metal22TitanumTi6 302Industrial metal25ManganeseMn1 156Industrial metal24ChromiumCr131Industrial metal28NickelNi90Industrial metal30ZincZn76Industrial metal29CopperCu59Industrial metal82LeadPb13Industrial metal50TinSn2.27Industrial metal74TungstenW1.29Industrial metal42MolybdenumMo1.27Industrial metal47Silver470.0750Precious metal46PalladiumPd0.0082Precious metal78PlatinumPt0.0036Precious metal79GoldAu0.0032Precious metal76OsmiumOs0.0018Precious metal44RutheniumRu0.0010Precious metal45RhodiumRh0.0010Precious metal77IridiumIr0.0008Precious metalSource: UNCTAD secretariat.other metals (e.g. silver, copper, platinum groupmetals). Gold is also used for monetary purposes (e.g.coinage), and as a safe-haven asset and investmentvehicle during periods of economic uncertainty.2. THE ROLE OF GOLD IN ECONOMIESGold plays a vital, multidimensional role in both localand international economies. In gold-producingdeveloping countries, it may account for a largeshare of their merchandise export revenues.3 Forinstance, it accounted for more than 40 per centof the export revenues of Mali, Burkina Faso andGuyana between 2009 and 2013, and for 56 percent in Suriname in 2013. Gold is also a sourceof substantial government revenues through taxes3Gold. Standard International Trade Classification, Revision3. 971, gold, non-monetary (excluding gold ores andconcentrates).

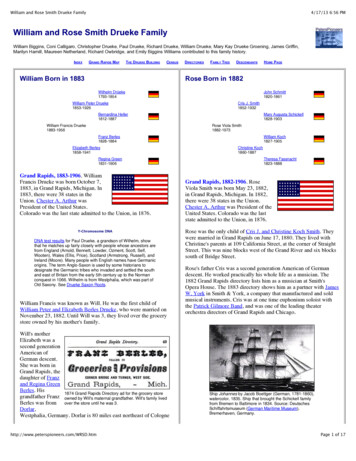

COMMODITIES AT A GLANCE - Special issue on gold4and royalties on mining and processing activities.Moreover, while activities associated with goldare generally capital-intensive, they neverthelessrepresent an important source of local employment,with about 50,000 people directly or indirectlyemployed by the gold sector in Australia4 and around300,000 people in South Africa, for instance. In all,according to World Gold Council estimates, about100 million people rely on gold mining activities fortheir livelihoods. 5The United States Geological Survey (USGS)estimates that world gold reserves stood at 54,000tons in 2014, representing about two decades ofproduction, in terms of current world production.6From a historical perspective, gold reserves havebeen located largely in South Africa (24 per centof world reserves, on average, between 1996 and2014). However, the country’s share in world goldreserves has been declining sharply over the period,falling from 41 per cent in 1996 to 11 per cent in2014. Since 2011, Australia has been the world’sleading gold reserves. As on February 2015, thethree main gold reserves were located in Australia,456Minerals Council of Australia, Australia’s gold industry:employment (see: nt/).See: Gold facts, at: http://www.goldfacts.org/en/.Based on 2012 production data; however, this computationdoes not take into account “reserve base” data or otheridentified and not already identified sources which are (orcould) be discovered and mined economically.South Africa and the Russian Federation (figure 1).Together, these three countries accounted for 38 percent of world reserves in 2014. Other gold reservesare widely spread around the world, with no countryhaving reserves exceeding 18 per cent of the worldtotal in 2014 (compared with 30 per cent in the caseof copper, for instance).Oceans could be a good potential reserve for gold.Indeed, oceans are estimated to contain up to 15,000tons of gold, according to the World Gold Council,which would represent more than a quarter of totalworld reserves, as estimated by the USGS in 2014.However, extraction of gold from the oceans iscurrently not considered economically viable.In addition to gold found in precious metaldeposits, it is also commonly recovered during thesmelting or refining processes of base metals. It isgenerally accepted that between 5 per cent and15 per cent of total gold worldwide is extracted asa by-product.3. RECENT HISTORY OF GOLD AS ACURRENCYUp to the end of the nineteenth century, the historyof gold may be divided into three main periods (figure2): (i) The gold standard system from 1870 to 1914,(ii) the Bretton Woods system, between the end ofthe Second World War and 1971; and (iii) the currentglobal free-floating exchange rate system whichstarted in 1971.Figure 1. Share of country gold reserves in total gold reserves, February 2015 (per cent)United States: 5Australia: 18Rest ofthe world:40Brazil: 4Chile: 7Indonesia: 5South Africa: 11Russian Federation: 9Source: UNCTAD secretariat, based on United States Geological Survey, Mineral Commodity Summaries, February 2015.

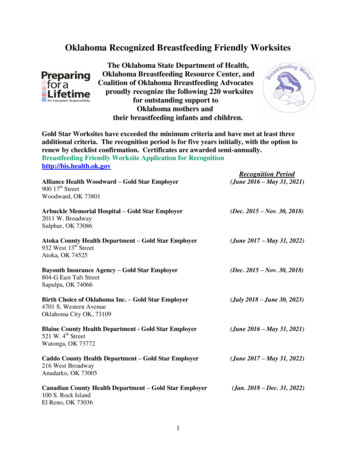

5CHAPTER 1 - INTRODUCTION From the gold standard to floating currenciesFigure 2. Overview of the recent history of goldUnited States President Rooseveltbans the possession of gold byUnited States citizens(1) End of the Bretton Woods system(2) Stop the convertibility of the dollar with gold End of the gold standard5 April 1933Executive order6102Sept. 1939London Gold Market(LGM) closesGOLD STANDARD1870–1914Classical goldstandardSept. 2011Gold price peaksat 1 77215 Aug. 1971Nixon closes thegold windowBRETTON WOODSFREE–FLOATING CURRENCIESMarch 1954Reopeningof the LGM31 Dec. 1974Executive order 1182522 July 1944Bretton Woodssystem1968Gold poolcollapses G. Ford restores theright of United Statescitizens to own goldBriefly reinstatedfrom 1925 to 1931,as the Gold ExchangeStandardDec. 2014Gold reaches 1,202/oz(1) US gold,Fixed rate of 35/oz(2) Other currencies pegged to US Source: UNCTAD secretariat.a. The Gold Standard system (1870 1914)The gold standard system, in place during the period1870 1914, used gold as the world’s commonunit of account. This meant that the value of eachparticipating currency was determined according toa specific weight in gold. Each currency could befreely converted into gold, and the nominal exchangerate between two currencies was fixed according totheir respective gold content. Within this system, themaximum amount of money that could be issuedby central banks was determined by the level of itsdomestic gold reserves. The gold standard hadalready been in place in the United Kingdom since1821, but the system was extended to cover othercountries during the 1870s.The gold standard system came to an end with thebeginning of the First World War. After a period of freefloating exchange rates from the end of the First WorldWar to the beginning of the Great Depression, a fewcountries joined forces to try to revive a system similarto that of the gold standard. However, the difficultpolitical situation, notably in Europe, fears regardinghigh inflation risks and the beginning of the GreatDepression, followed by the Second World War, ledto the definitive collapse of the gold standard system.b. The Bretton Woods system (1944 1971)Named after the New Hampshire town where theBretton Woods Agreement was signed, the BrettonWoods system aimed at establishing an adjustablepeg currency regime. Each of the participatingcountries was required to fix its exchange rate by tyingit to the United States dollar, which itself was peggedto gold at a fixed value of 35 per troy ounce. TheUnited States currency was chosen as a referenceas that country held three fourths of the world’s goldstocks at that time.

The system was more flexible than the former goldstandard system as the Bretton Woods Agreementallowed a fluctuation of the parity of currencies withina range of more or less 1 per cent around the peg.This flexibility was expected to allow the correctionof fundamental disequilibria. Outside this range,stakeholders were required to intervene by buying orselling their currency.c. The end of the Bretton Woods system andthe start of a free-floating exchange ratesystem (1971 to the present)From the beginning of the 1960s, the US dollarstarted to be seen as overvalued compared with thevalue defined in the Bretton Woods Agreement. Asa result of the rapid expansion of international tradeand military spending, the volume of US dollars incirculation increased dramatically and finally exceededthe value of gold effectively held by the United States(at the rate of 35 per troy ounce). The Bretton Woodssystem collapsed in 1971, following the decision of theUnited States President, Richard Nixon, to suspendthe convertibility of the US dollar into gold. Since1973, most countries have turned to a free-floatingexchange rate system, or to the adoption of anothercountry’s currency (e.g. the adoption of the US dollarin Ecuador in 2001),7 or to the creation of a singlecurrency in a monetary union, as in Europe.7Central Intelligence Agency, The World Factbook worldfactbook/geos/ec.html).

7CHAPTER 4 - PRICESCHAPTER 2:USES

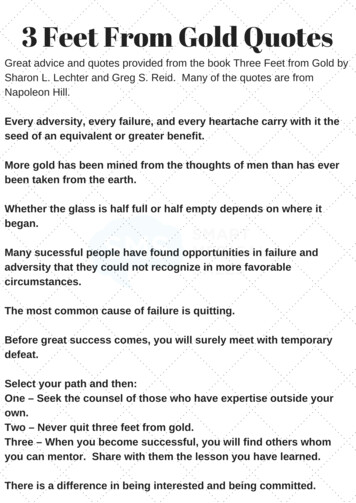

9CHAPTER 2 - USESThe history of gold dates back to at least 5,000years ago, and demand for it has been expandingcontinuously in both quantity and types of uses.In recent times, after a sharp slowdown of worlddemand from 2000 to 2003 (by 25 per cent), thedemand for gold started to rise again between 2004and 2007. On average, 2,900 tons were tradedannually during this latter period. In 2008, as a resultof the global financial and economic crisis, demandfor gold accelerated, reaching 4,515 tons in 2011 andlater peaking at 5,042 tons in 2013. In 2014, demanddeclined by 17.5 per cent, to 4,159 tons (figure 3).Demand for gold mainly results from a combinationof purchases made for (1) jewellery fabrication, (2)industrial purposes, (3) investments in the form ofbars and coins, exchange traded funds (ETFs) orsimilar products, and, (4) net sales by central banks.The historical background of these various sectorsand subsectors that have been the source of globaldemand for gold since the beginning of the 2000s isdiscussed below, as well as potential developments inthe years to come.1. JEWELLERYSince the discovery of gold, it has mainly been usedfor making jewellery. Traditionally, gold has been highlyappreciated for its lustre, resistance to tarnishing andcorrosion, and its malleability and ductility, whichallow it to be crafted into various shapes. Moreover,thanks to its scarcity and globally recognized beauty,it is highly valued in the production of objects usedin special events, such as wedding rings. But gold isalso used for the production of religious items and forthe fabrication and restoration of artistic objects (e.g.gold leaves).For jewellery, gold can be used in its pure form.However, because of its softness, it is often alloyedwith other metals, such as silver and copper. Althoughthese alloys are less resistant to tarnishing, they arealso less expensive than pure gold. A standard oftrade known as “karatage” has been developedto define and harmonize the gold content of alloys.Pure gold of 24 karats (a ratio of 24 out of 24) is thebenchmark, whereas an alloy containing 75 per centof gold is said to be 18 karat gold (18 out of 24). Thepreferred karatage varies by country. For instance, inFrance, 18 karats is the reference for jewellery madeof gold, while 22 karats and 14 karats are used morein India and the United States respectively.In some developing countries where a large proportionof the population does not have easy access to thefinancial and banking system, gold is often used as ameans of storing value, preserving wealth and passingdown savings to heirs. For this reason, falling goldprices can have a direct negative impact on vulnerablelocal populations.Between 2005 and 2014, jewellery remained by farthe largest gold-consuming sector, accounting forFigure 3. Historical evolution of world demand for gold, and distribution of the demand by sector, 2000 2014 (tons)6 0005 0004 0003 0002 0001 0000JewelleryTechnologyInvestmentCentral bank net purchasesSource: UNCTAD secretariat based on Thomson Reuters Eikon (accessed 8 April 2003200220012000-1 000World demand

COMMODITIES AT A GLANCE - Special issue on gold1056 per cent of total world demand, though this wasa significant decline from the year 2000, when itaccounted for 84 per cent.In recent years, demand for gold for jewellery hasbeen mainly concentrated in Asia (figure 4), with Chinaand India in the lead. Their combined share in worlddemand has nearly doubled during the past decade(from 32.1 per cent in 2005 to 60 per cent in 2014).Figure 4. Demand for gold by jewellery sector:geographical distribution, 2014 (per cent)Europe15India 31NorthAmerica 3SouthAmerica 2Africa 3Oceania 0.1China29Asia(excludin

already been mined in human history. They include all stocks of jewellery, gold held by central banks and private investors, as well as all gold fabricated products. All-in sustaining costs (AISC): is a voluntary non-GAAP [Generally Accepted Accounting Principles] measure proposed by