Transcription

Art Directors & TRIP / AlamyAFTER STUDYING THIS CHAPTER, YOU SHOULD BE ABLE TO1define sustainable marketing and discuss its importance2identify the major social criticisms of marketing3define consumer activism and environmentalism, and explain how they affect marketing strategies4describe the principles of sustainable marketing5explain the role of ethics in marketingM03 ARMS3141 CH03 p078-115.indd 784th Proof14/01/14 11:59 AM

CHAPTERSustainable Marketing SocialResponsibility and Ethics3Previewing the ConceptsIn this chapter, we’ll examine the concepts of sustainable marketing, meeting the needs of consumers,businesses, and society—now and in the future—through socially and environmentally responsible marketing actions. we’ll start by defining sustainable marketing and then look at some common criticisms ofmarketing as it impacts individual consumers and public actions that promote sustainable marketing.Finally, we’ll see how companies themselves can benefit from proactively pursuing sustainable marketingpractices that bring value not just to individual customers but also to society as a whole. You’ll see thatsustainable marketing actions are more than just the right thing to do; they’re also good for business.First, let’s look at an example of sustainable marketing in action at Unilever, the world’s third-largestconsumer products company. For 12 years running, Unilever has been named sustainability leader in thefood and beverage industry by the Dow Jones Sustainability Indexes. The company recently launched itsSustainable Living Plan, by which it intends to double its size by 2020 while at the same time reducing itsimpact on the planet and increasing the social benefits arising from its activities. That’s an ambitious goal.SUSTAINABILITY AT UNILEVER: CREATING A BETTER FUTUREEVERY DAYWhen Paul Polman took over as CEO of Unilever in 2009, the home and personal careproducts company was a slumbering giant. Despite its stable of star-studded brands—including the likes of Dove, Axe, Noxema, Sunsilk, VO5, Hellmann’s, Lipton, and Ben &Jerry’s—Unilever had experienced a decade of stagnant sales and profits. The companyneeded renewed energy and purpose. “To drag the world back to sanity, we need to knowwhy we are here,” said Polman.To answer the “why are we here” question and find a more energizing mission, Polmanlooked beyond the usual corporate goals of growing sales, profits, and shareholder value.Instead, he asserted, growth results from accomplishing a broader social and environmental mission. Unilever exists “for consumers, not shareholders,” he said. “If we are in syncwith consumer needs and the environment in which we operate, and take responsibility forour [societal impact], then the shareholder will also be rewarded.”As a result of such thinking, in 2010 Unilever launched its Sustainable Living Plan.Under this plan, the company set out to “create a better future every day for peopleM03 ARMS3141 CH03 p078-115.indd 794th Proof09/01/14 12:36 PM

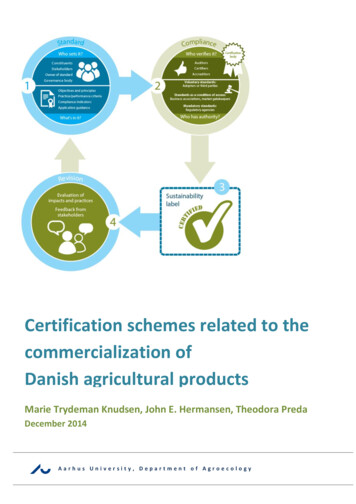

80PART 1 Defining Marketing and the Marketing Processaround the world: the people who work for us, those we do business with, the billions ofpeople who use our products, and future generations whose quality of life depends on theway we protect the environment today.” According to Polman, Unilever’s long-run commercial success depends on how well it manages the social and environmental impact ofits actions.The Sustainable Living Plan sets out three major social and environmental objectivesto be accomplished by 2020: “(1) To help more than one billion people take action toimprove their health and well-being; (2) to halve the environmental footprint of the makingand use of our products; and (3) to source 100 percent of our agricultural raw materialssustainably.”Evaluating and working on societal and environmental impact is nothing new atUnilever. The company already had multiple programs in place to manage the impact of itsproducts and operations. For example, over the past five years, the company’s NutritionEnhancement Program has reviewed Unilever’s entire portfolio of foods—some 30 000products—resulting in reductions in saturated and trans fat, sugar, and salt in thousands ofitems. And over the past decade, the company’s factories have reduced CO2 emissions by44 percent, water use by 66 percent, and total waste disposal by 73 percent. However, theSustainable Living Plan pulls together all of the work the company has been doing and setsambitious new sustainability goals.Unilever’s sustainability efforts span the entire value chain, from how the companysources raw materials to how customers use and dispose of its products. “The world facesenormous environmental pressures,” says the company. “Our aim is to make our activitiesmore sustainable and also encourage our customers, suppliers, and others to do thesame.” On the “upstream supply side,” more than two-thirds of Unilever’s raw materialscome from agriculture, so the company is helping suppliers develop sustainable farmingpractices that meet its own high expectations for environmental and social impact. Unileverassesses suppliers against two sets of standards. The first is the Unilever Supplier Code,which calls for socially responsible actions regarding human rights, labour practices, product safety, and care for the environment. The second is the Unilever Sustainable AgricultureCode, which details Unilever’s expectations for sustainable agriculture practices, so that itand its suppliers “can commit to the sustainability journey together.” Unilever also collaborates closely with its commercial and trade customers, such as Walmart and other largeretailers, many of whom have their own ambitious goals in areas such as energy use,greenhouse gas emissions, recycling, and waste reduction.But Unilever’s Sustainable Living Plan goes far beyond simply creating more responsible supply and distribution chains. Unilever is also working with final consumers to improvethe social and environmental impact of its products in use. More than 2 billion customers in178 countries use a Unilever product on any given day. Therefore, small everyday customeractions can add up to a big difference. Unilever sums it up with this equation: “Unileverbrands small everyday events billions of consumers big difference.”For example, almost one-third of households worldwide use Unilever laundry productsto do their washing—approximately 125 billion washes every year. Up to 70 percent of thetotal greenhouse gas footprint of Unilever’s laundry products and 95 percent of the waterfootprint occur during consumer use. Therefore, under its Sustainable Living Plan, Unileveris both creating more eco-friendly laundry products and motivating consumers to improvetheir laundry habits.M03 ARMS3141 CH03 p078-115.indd 804th Proof09/01/14 12:36 PM

Chapter 3 Sustainable Marketing Social Responsibility and EthicsFor example, around the world, Unilever is encouraging consumers to wash clothes atlower temperatures and use the correct dosage of detergent. One Unilever product, PersilSmall & Mighty laundry detergent, is a concentrated detergent that uses less packaging,making it cheaper and less polluting to transport. More importantly, it washes better atlower temperatures and uses less energy. Another Unilever product, Comfort One Rinsefabric conditioner, was created for hand-washing clothes in developing and emerging markets where water is often in short supply. The innovative product requires only one bucketof water for rinsing rather than three, saving customers time, effort, and 30 litres of waterper wash. Such energy and water savings don’t show up on Unilever’s income statement,but they will be extremely important to the people and the planet. Similarly, small changesin product nutrition and customer eating habits can have a surprisingly big impact onhuman health. “In all,” says the company, “we will inspire people to take small, everydayactions that can add up to a big difference for the world.”Will Unilever’s Sustainable Living Plan produce results for the company? It is still toosoon to tell, but so far, so good. Last year, Unilever’s revenues grew 11 percent while profits grew 26 percent. The sustainability plan is not just the right thing to do for people andthe environment, claims Polman, it’s also right for Unilever. The quest for sustainabilitysaves money by reducing energy use and minimizing waste. It fuels innovation, resulting innew products and new customer benefits. And it creates new market opportunities: Morethan half of Unilever’s sales are from developing countries, the very places which face thegreatest sustainability challenges.In all, Polman predicts, the sustainability plan will help Unilever double in size by 2020,while also creating a better future for billions of people without increasing the environmental footprint. “We do not believe there is a conflict between sustainability and profitablegrowth,” he concludes. “The daily act of making and selling consumer goods drives economic and social progress. There are billions of people around the world who deserve thebetter quality of life that everyday products like soap, shampoo, and tea can provide.Sustainable living is not a pipedream. It can be done, and there is very little downside.”1*81*Excerpts, quotes, and otherinformation from T. L. Stanley,“Easy As Pie: How Russell WeinerTurned Sabotage Into Satisfaction,” Adweek, September 13,2010, p. 40; “Lessons from theDomino’s Turnaround,” Restaurant Hospitality, June 2010, p. 30;Rupal Parekh, “Marketer of theYear,” Advertising Age, October18, 2010, p. 19; Emily BrysonYork, “Domino’s Claims Victorywith New Strategy: Pizza Wasn’tGood, We Fixed It,” AdvertisingAge, May 10, 2010, p. 4; MarkBrandau, “Domino’s Do-Over,”— Nation’s Restaurant News, March8, 2010, p. 44; “Domino’s PutsCustomer Feedback on TimesSquare Billboard,” Detroit News,July 26, 2011; and annual reportsand other information from www.dominosbiz.com and www.pizzaturnaround.com, accessedDecember 2011.RESPONSIBLE marketers such as Unilever discover what consumers want andrespond with market offerings that create value for buyers in order to capture value inreturn. The marketing concept is a philosophy of customer value and mutual gain. Not allmarketers follow the marketing concept, however. In fact, some companies use questionable marketing practices that serve their own rather than consumers’ or society’s interests. Responsible marketers must consider whether their actions are sustainable in thelonger run.Consider the sport-utility vehicles (SUVs). These large vehicles meet the immediateneeds of many drivers in terms of capacity, power, and utility, however, they raise largerquestions of consumer safety and environmental responsibility. For example, in accidents, SUVs are more likely to kill both their own occupants and the occupants of othervehicles. Moreover, SUVs are gas guzzlers. According to Sierra Club, a well known environmental activist group, switching from an average car to an SUV wastes more energyper year than if you left your refrigerator door open for 6 years, or left your bathroomlight burning for 30 years!2This chapter examines sustainable marketing and the social and environmental effects of private marketing practices. First, we address this question: What is sustainablemarketing and why is it important?M03 ARMS3141 CH03 p078-115.indd 814th Proof13/01/14 12:45 PM

82PART 1 Defining Marketing and the Marketing ProcessSustainable MarketingSustainable marketingSocially and environmentallyresponsible marketing that meets thepresent needs of consumers andbusinesses while also preserving orenhancing the ability of futuregenerations to meet their needs.lo1Sustainable marketing calls for socially and environmentally responsible actions thatmeet the present needs of consumers and businesses while also preserving or enhancingthe ability of future generations to meet their needs. Figure 3.1 compares the sustainablemarketing concept with other marketing concepts we studied in Chapter 1 and 2.3The marketing concept recognizes that organizations thrive from day to day by determining the current needs and wants of target group customers and fulfilling thoseneeds and wants more effectively and efficiently than competitors do. It focuses on meeting the company’s short-term sales, growth, and profit needs by giving customers whatthey want now. However, satisfying consumers’ immediate needs and desires doesn’t always serve the future best interests of either customers or the business.Whereas the societal marketing concept identified in Figure 3.1 considers the futurewelfare of consumers and the strategic planning concept considers future company needs,the sustainable marketing concept considers both. Sustainable marketing calls for sociallyand environmentally responsible actions that meet both the immediate and future needsof customers and the company.Consider McDonald’s. The company’s early decisions to market tasty but fat- andsalt-laden fast foods created immediate satisfaction for customers and sales and profitsfor the company, but in the 1990s critics and activists began to blame fast food chains forcontributing to the obesity problem, burdening the national health system, and causingunnecessary pollution and waste on a global scale. It was not a sustainable strategy, butin recent years, all that’s changed.4For the last decade McDonald’s has undertaken many initiatives to change its corporate philosophy to one of sustainability, beginning by appointing a Senior Vice President, GlobalCorporate Social Responsibility, Sustainability and Philanthropy. The company is aware thatit has a significant global “footprint”—with nearly 2 million employees and more than 5000franchisees serving 69 million customers every day in 118 countries. McDonald’s believesthat because of their size, scope, and scale, they have the ability to make positive differencesin the world—the very definition of sustainability. In 2007 the company created a corporategovernance body called the Sustainable Supply Steering Committee (SSSC), responsible forguiding McDonald’s toward their vision for sustainable supply by identifying global prioritiesand ensuring progress in ways that complement local priorities and efforts.For example, McDonald’s sustainable supply chain initiative means endeavouring topurchase from suppliers that follow practices that ensure the health and safety of theiremployees and the welfare and humane treatment of animals. In the sourcing of materialsand production of packaging and other products, McDonald’s works with companies thatmanufacture and distribute products in a way that minimizes impact on the environment. Inaddition, global suppliers of major products like beef and potatoes are also required to takeon product-specific sustainability initiatives in their strategies.In addition to the corporation’s global initiatives, McDonald’s Canada is actively engagedin national energy saving practices. For example, each year during Earth Hour, a global initiativeNeeds of consumersFigure 3.1 Sustainable MarketingNowMarketing conceptStrategic planningconceptFutureSocietal reNeeds of businessM03 ARMS3141 CH03 p078-115.indd 824th Proof09/01/14 12:36 PM

Sustainable Marketing Social Responsibility and Ethics83led by the World Wildlife Fund (WWF),McDonald’s restaurants turn off their road signsand roof beams, and other lights, and in that onehour, across Canada, the company saves morethan 10 000 kWh of electricity—approximatelythe amount required to run one Canadianhousehold for a full year. And through energysaving practices in the areas of ventilation,lighting, and heating, McDonald’s restaurants inCanada have saved an estimated 11.7 millionkWh and 770 000 cubic meters of natural gassince 2005, which equates to 4033 metric tons ofcarbon dioxide emissions—equal to takingapproximately 739 cars off the road. In addition,two restaurants in Quebec have pioneered theuse of a geothermal renewable energy system—a means of extracting heat from the earth—inthe operation of quick-service restaurants.McDonald’s Canada also engages its supExhibit 3.1 Sustainable marketing: McDonald’s sustainability strategy has created value forpliers and encourages them to be more environcustomers and positioned the company for a profitable future.mentally conscious. This led to the creation in2007 of an annual Sustainability Award, whichrecognizes a supplier who has demonstrated a commitment to advancing environmental sustainability in the areas of energy conservation, solid waste mitigation and recycling, amongothers. McDonald’s Canada also recently opened its first green restaurant in Beauport (Quebec),which is a candidate for LEED Certification. (The Leadership in Energy and EnvironmentalDesign (LEED) green building rating system encourages and accelerates global adoption ofsustainable green building and development practices in Canada and the US.) As a result ofits sustainability initiatives, McDonald’s has been a member of the Dow Jones SustainabilityIndex since 2005, and was named one of the Greenest Companies in America by Newsweekmagazine in 2010. Truly sustainable marketing requires a smooth-functioning marketingsystem in which consumers, companies, public policy-makers, and others work together toensure socially and environmentally responsible marketing actions. Unfortunately, however,the marketing system doesn’t always work smoothly. The following sections examine severalsustainability questions: What are the most frequent social criticisms of marketing? Whatsteps have private citizens taken to curb marketing ills? What steps have legislators andgovernment agencies taken to promote sustainable marketing? What steps have enlightenedcompanies taken to carry out socially responsible and ethical marketing that creates sustainablevalue for both individual customers and society as a whole?Social Criticisms of MarketingAlexandre Gelebart/Redux PicturesChapter 3lo2Marketing receives much criticism. Some of this criticism is justified; much is not. Socialcritics claim that certain marketing practices hurt individual consumers, society as awhole, and other business firms.Marketing’s Impact on ConsumersConsumers have many concerns about how well the marketing system serves their interests. Surveys usually show that consumers hold mixed or even slightly unfavourable attitudes toward marketing practices. Consumer advocates, government agencies, andother critics have accused marketing of harming consumers through high prices, deceptive practices, high-pressure selling, shoddy or unsafe products, planned obsolescence,and poor service to disadvantaged consumers. Such questionable marketing practicesare not sustainable in terms of long-term consumer or business welfare.M03 ARMS3141 CH03 p078-115.indd 834th Proof09/01/14 12:36 PM

84PART 1 Defining Marketing and the Marketing ProcessHigh Prices Many critics charge that the marketing system causes prices to be higherthan they would be under more “sensible” systems. Critics point to three factors—highcosts of distribution, high advertising and promotion costs, and excessive markups.A long-standing charge is that channel intermediariesmark up prices beyond the value of their services. Critics charge that there are too many“middlemen,” and that they are inefficient, or that they provide unnecessary or duplicateservices. As a result, distribution costs too much, and consumers pay for these excessivecosts in the form of higher prices.As we’ll learn in Chapter 11, marketing intermediaries provide a variety of servicesin the chain of distribution—the movement of products from their source of productionto the hands of the final customer. The planning, organization, and ongoing management of these channels is an expensive proposition for any firm, and since all firms areconcerned about their bottom line, any channel partners or intermediaries who were notadding value would quickly be cut from the process.HIGH COSTS OF DISTRIBUTIONModern marketing is also accused of pushing up prices to finance heavy advertising and sales promotion. For example, a few dozentablets of a heavily promoted brand of pain reliever sell for the same price as 100 tabletsof less-promoted brands. Differentiated products—cosmetics, detergents, toiletries—include promotion and packaging costs that can amount to 40 percent or more of themanufacturer’s price to the retailer. Critics charge that much of the packaging andpromotion adds only psychological value to the product rather than functional value.Marketers respond that although advertising is expensive, it also adds value by informing potential buyers of the availability and merits of a product. Brand name productsmay cost more, but branding gives buyers assurances of consistent quality. Moreover, consumers can usually buy functional versions of products at lower prices. However, theywant and are willing to pay more for products that also provide psychological benefits—that make them feel wealthy, attractive, or special. Also, advertising and promotion aresometimes necessary, especially for marketers of products such as consumer electronics,cars, and personal care products—product categories in which there exist many brandsand many competitors. Otherwise, the firm would not be able to compete.Though it may seem logical that because advertising is expensive and therefore iffirms did no advertising the price of their products would go down, this is in fact a fallacy. Without advertising, sales would decrease,therefore production would decrease. Whenfewer products are manufactured, the price tomanufacture each product goes up—and priceswould go up correspondingly. Recently in theUK, consumer activists called for more regulation in the advertising of children’s toys, and argued that all toy advertising should be banned.But economics researcher and journalist ChrisSnowdon argued that the prohibition of advertising would lead to monopolistic markets resulting in higher prices for consumers.5 Mira / AlamyHIGH ADVERTISING AND PROMOTION COSTSExhibit 3.2 Criticisms of marketing: A heavily promoted brand of Aspirin sells for much morethan a virtually identical nonbranded or store-branded product. Critics charge that promotionadds only psychological value to the product rather than functional value.M03 ARMS3141 CH03 p078-115.indd 844th ProofEXCESSIVE MARKUPS Critics also charge thatsome companies mark up goods excessively.They point to the drug industry as an example ofthe worst offenders, where a pill costing fivecents to make may cost the consumer 2 to buy.Marketers sometimes respond that consumers09/01/14 12:36 PM

Chapter 3 Sustainable Marketing Social Responsibility and Ethics85often don’t understand the reasons for high markups. For example, pharmaceuticalmarkups must cover the costs of purchasing, promoting, and distributing existing medicines plus the high research and development costs of formulating and testing new medicines—all of which is very expensive. The simple fact is, all companies are in business tooffer something of value to the market, and producing that market offering involvesmuch more than just the costs of the manufacturing process.Most businesses try to deal fairly with their customers because they want to buildrelationships and repeat business—it’s simply not in their own best interests to cheat ormislead those customers. There are, of course, exceptions to the rule, and when consumers perceive any abuse of marketing, whether it’s false advertising, or unfair pricing, theyshould report those abuses to their local Better Business Bureaus or to the provincialConsumer Affairs office.consumers to believe they will get more value than they actually do. Deceptive practicesfall into three groups: pricing, promotion, and packaging. Deceptive pricing includes practices such as falsely advertising “factory” or “wholesale” prices or a large price reduction froma phony high retail list price. Deceptive promotion includes practices such as misrepresenting the product’s features or performance or luring the customers to the store for a bargainthat is out of stock. Deceptive packaging includes exaggerating package contents throughsubtle design, using misleading labelling, or describing size in misleading terms.In Canada, the Competition Bureau acts as a watchdog to prevent such practices.They are alerted to instances of deceptive marketing through consumer complaints, andthey do take action. For example, they recently took Rogers Communications to courtand charged the telecommunications giant with violating Canada’s false advertising ruleswhen they claimed their Chatr cellphone service had “fewer dropped calls” than thecompetition. The Bureau charged that Rogers produced “false and misleading” ads, andfailed to back up its claims about dropped calls with “adequate and proper tests,”—andsought to impose a 10 million fine.6 And just two years earlier, the federal watchdogforced Bell Canada to stop making what the Bureau had concluded were misleadingrepresentations about the prices offered for its services—and required them to pay apenalty of 10 million, the maximum amount allowed under the Competition Act.7In addition to the long standing rules enforced by the Competition Bureau, new federal, provincial, and municipal guidelines and regulations are created as they becomenecessary. For example, as a result of claims of“greenwashing”—companies that claim to beenvironmentally friendly in some way, butwho are not really doing what they claim to bedoing—in 2008, the Competition Bureau incollaboration with the Canadian StandardsAssociation issued guidelines to provide thebusiness community with tools to ensure thatgreen marketing claims are not misleading.8Companies who greenwash should takenote: consumers everywhere are paying attention and crying foul when they perceivethey’ve been greenwashed. In a recent survey, four out of five residents of the UK saidthey suspect companies of trying to get awaywith false claims of green marketing. ThatExhibit 3.3 Deceptive practices: Despite plenty of regulation, some critics argue thatcountry’s watchdog organization, the Adverdeceptive claims are still the norm. Consider all of those “green marketing” claims.tising Standards Authority (ASA) receivedM03 ARMS3141 CH03 p078-115.indd 854th Proof [2013] UL LLC. Reprinted with permission.Deceptive Practices Marketers are sometimes accused of deceptive practices that lead09/01/14 12:36 PM

86PART 1 Defining Marketing and the Marketing Process93 complaints about 40 different ads in one month alone. Among the offenders wereLexus, who ran an ad with the headline “High Performance. Low Emissions. Zero Guilt,”deemed to give the misleading impression that the car caused little or no harm to theenvironment. Likewise Volkswagen ran an ad that promised their car was “better for theplanet,”—which was banned by the ASA because the claims were “too general.”9 And intoday’s always online and socially connected universe, offenders not only get caught, butinformation about their offences is quickly spread through social media.The toughest problem is defining what is “deceptive.” One noted marketing thinker,Theodore Levitt, once claimed that advertising puffery and alluring imagery are boundto occur—and that they may even be desirable: “There is hardly a company that wouldnot go down in ruin if it refused to provide fluff, because nobody will buy pure functionality. . . . Worse, it denies people’s honest needs and values. Without distortion,embellishment, and elaboration, life would be drab, dull, anguished, and at its existential worst.”10In today’s world of marketing, the term puffery actually has meaning in a legalsense. The law in Canada and in the US recognizes that some statements made in advertising are not intended to be taken literally, and are therefore not illegal. A famousexample that is often cited is the Barnum & Bailey Circus promoting itself as “the greatest show on earth.” Puffery and hyperbole—extreme exaggeration for effect—are thestaples of advertising.Though it is sometimes debatable what constitutes deception, Ontario’s ConsumerProtection Act lays down some pretty clear definitions of false, misleading, and deceptive marketing practices:1. A representation that the goods or services have sponsorship, approval, performance characteristics, accessories, uses, ingredients, benefits, or qualities they donot have.2. A representation that the person who is to supply the goods or services has sponsorship, approval, status, affiliation, or connection the person does not have.3. A representation that the goods or services are of a particular standard, quality,grade, style, or model, if they are not.4. A representation that the goods are new or unused; if they are not, or are recon ditioned or reclaimed, but the reasonable use of goods to enable the person toservice, prepare, test, and deliver the goods does not result in the goods beingdeemed to be used for the purposes of this paragraph.5. A representation that the goods have been used to an extent that is materially different from the fact.6. A representation that the goods or services are available for a reason that does notexist.7. A representation that the goods or services have been supplied in accordance witha previous representation, if they have not.8. A representation that the goods or services or any part of them are available or canbe delivered or performed when the person making the representation knows orought to know they are not available or cannot be delivered or performed.9. A representation that the goods or services or any part of them will be availableor can be delivered or performed by a specifi d time when the person making therepresentation knows or ought to know they will not be available or cannot bedelivered or performed by the specifi d time.10.

The first is the Unilever Supplier Code, which calls for socially responsible actions regarding human rights, labour practices, prod-uct safety, and care for the environment. The second is the Unilever Sustainable Agriculture Code, which details Unilever’s expectations for