Transcription

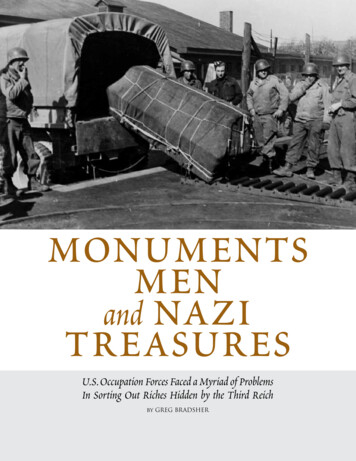

monumentsmenand nazitreasuresU.S. Occupation Forces Faced a Myriad of ProblemsIn Sorting Out Riches Hidden by the Third Reichby GreG Bradsher

In late Januar y 1945, Russian troops moved closer to the massive Tannenberg Memorial nearHohenstein, in what is now Olsztynek in northern Poland near the Baltic Sea.It commemorated the German soldiers killed there in World War I.And it was a battle in whichthe German commander, Paul von Hindenberg , who was later elected president, became a hero.Colonel-General Hans Reinhardt, commander of ArmyGroup Center, ordered the memorial to be blown up, butnot before certain things were removed. Those things werethe bodies of Field Marshal and Weimar President vonHindenburg and his wife. Lt. Gen. Oskar von Hindenburgsupervised the evacuation of the flags of the Prussian regi ments and the coffins of his parents, which were moved toBerlin.Thus began what a 1950 Life magazine article called “oneof the most curious and complicated enterprises the U.S.Army of Occupation ever undertook.”It was perhaps one of the most unlikely and interest ing World War II German cultural property evacuationendeavors. The story involves four caskets; military flags;famous artwork; the Hohenzollern Museum treasure (fromthe Monbijou Palace in Berlin), including the crown jewelsand the coronation paraphernalia of Frederick William I;and cultural treasures.In March 1945, the German Army transported thecaskets of the Hindenburgs, Frederick the Great, andFrederick William I, as well as the cultural items namedabove, to a one-time salt mine in the northern reachesof the Thuringian Forest, about 18 miles southwest ofNordhausen, that had been converted to a munitions plantand storage depot.There, German Army officers supervised 2,000 Italian,French, and Russian forced laborers working in the plant.About 400,000 tons of ammunition and other militarysupplies were stored in the mine.A group of large warehouses adjacent to the entranceinto the shaft contained munitions, signal supplies, cloth ing, and other military stores. A large store of dynamite waslocated in relatively close proximity to the depository in themine. Two rooms in the mine already stored records.German officers sent all civilians out of the area in midMarch. Working with great secrecy and using only militarypersonnel, they brought objects into the mine.Opposite: The casket of Frederick the Great is removed from theBernterode cave southwest of Nordhausen, Germany, in April 1945.Monuments Men and Nazi TreasuresIn a room measuring roughly 45 x 17 feet, they placedthe caskets of Prussian kings Frederick William I (reign1713–1740) and Frederick the Great (1740–1786), bothof whom had been buried in the church of the Potsdamgarrison, and of Field Marshal and Frau Gertrud vonHindenburg. Three of the caskets were made of wood; thefourth, containing the remains of Frederick the Great, wasmetal and larger than the others. Each casket bore a paperlabel fastened with cellophane tape.In the same room the soldiers also placed treasures fromthe Hohenzollern Museum in Berlin. Each item had anidentifying card attached. Most of the items had beenmade for or used at the coronation of King Frederick I andQueen Sophie in 1701. More than 200 German regimen tal flags, some painted and some embroidered, were hungabove the coffins. They dated from the early Prussian warsand included many from the World War I era. A varietyof other cultural items were placed in the room, and theentrances were sealed with brick and mortar on April 2.Officers with Art ExpertiseArrive to Supervise OperationsThe items were not concealed for long. By the end ofApril, the mine treasure would be in American hands. Notlong afterward, the caskets, paintings, and flags would bestored in Marburg, awaiting political decisions as to whatto do with them.Marburg is situated on a hillside along the Lahn River,60 miles north of Frankfort. From a military standpoint in1945, Marburg was important for its marshalling yards atthe south end of town, which were used for the transship ment of German military personnel and supplies.The U.S. Army Air Forces bombed the yards four timesin March. The historic buildings in the central part of thetown were undamaged from these bombings, but the newStaatsarchiv Building (occupied in 1938), suffered moder ate damage.Not long after the last aerial bombardment of Marburg,the American military forces entered the town and cap tured it by the end of March.Prologue 13

When American forces entered the Bernterodesalt mine in April 1945. they found four casketsin a chamber. The coffin of Frederick Wilhelm Iis not pictured. Left, top: Frederick the Great; bottom: Frederick's bronze coffin draped with a Naziflag. Center, top: Field Marshal and President Paulvon Hindenburg; bottom: von Hindenburg's coffin.Above: The casket of Frau von Hindenburg in theBernterode cave.Soon thereafter, in early April, Capt.Walker K. Hancock inspected the pri mary cultural institutions and locations.Hancock was an officer specialist withthe Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives(MFA&A) Section, whose members wereknown as the “Monuments Men.” As a re nowned sculptor, Hancock had won theprestigious Prix de Rome before the war anddesigned the Army Air Medal in 1942. Atthe castle, he found three great halls packedwith parcels from the Staatsarchiv andMarburg town archives. At the Staatsarchivhe found that the building and its archivalholdings had sustained greater damage fromthe occupying troops than from the bombs.While Hancock was dealing with the situ ation in and around Marburg, other U.S.troops came across the Bernterode salt mine.During their inspection of the mine, theyobserved a masonry wall built into the sideof the main corridor about 550 yards fromthe elevator shaft.Noticing that the mortar was still fresh,they made an opening and, after tunneling14 Prologuethrough masonry and rubble to a depth ofmore than five feet, uncovered a latticeddoor padlocked on the opposite side.Breaking through, they entered a roomdivided into a series of compartments hungwith brilliant flags and filled with paintings,boxes, and tapestries. The contents weregrouped around four caskets, one of whichhad been decorated with a wreath and redsilk ribbons bearing Nazi symbols and thename Adolf Hitler.An inspection of the room the followingday, April 28, brought to light a richly jew eled scepter and orb, two crowns, and twoswords with finely wrought gold and silverscabbards. Hancock inspected the deposi tory the next day and later wrote:Crawling though the opening intothe hidden room, I was at once forciblystruck with the realization that this wasno ordinary depository of works of art.The place had the aspect of a shrine. Thesymmetry of the plan, a central passage way with three compartments on eitherside connecting two large end bays; thedramatic display of the splendid flags,hung in deep rows over the casketsand stacked with decorative effect inthe corners; the presence of the casketsthemselves; all suggested the setting fora modern pagan ritual. The pictures inthe entrance bay . . . seemed to havebeen brought in as an afterthought.Two hundred and seventy-one artworks,many of them 18th-century court portraitsand paintings apparently from the SansSouci palace at Potsdam, lay scattered about.There were also several works of LukasCranach the Elder from a 1937 Berlin exhi bition, and works by noted artists Boucher,Watteau, and Chardin.On the right of the central passagewaywere three wooden coffins, with the iden tifications indicating they contained theHindenburgs and Frederick William I. Inthe last compartment on the left was thegreat metal casket of Frederick the Great.Near that casket was a small metal box,from the Kriegschule in Potsdam, contain ing 24 photographs in color (with copiesSummer 2013

in black-and-white) of portraits of Germanmilitary commanders from FrederickWilliam I to Hitler.A large heap of tapestries and altar clothslay damp and unwrapped by the door. Therewere 65 steel ammunition boxes and cases ofbooks, some with the stamp of the CrownPrince’s Library, and some china in boxes.The Art Experts FindTreasures of a Nazi FutureHancock telephoned another MonumentsMan at 12th Army Group Headquarters,Navy Reserve Lt. George Stout, one ofAmerica’s foremost experts in the field of artconservation. He told Stout that he was at amine “with 400,000 tons of explosives in it.I can’t tell you what else is down there, notover the phone, but it’s important, George.Maybe even more important than Siegen[another mine that contained works of artand treasures].”Because of the precarious conditions atthe depository, the Army ordered its evacu ation, with the coronation paraphernaliagoing to headquarters and everything elsemoved to a place of safety. Stout was orderedto go to Bernterode to give technical adviceon the removal of the artworks and otherhistorical holdings.When Hancock and Stout went into themine and reviewed the treasures on May 1,Stout observed that the Germans were hiding“the most precious artifacts of the Germanmilitary state. This room wasn’t intended forHitler; it was intended for the next Reich, sothey could build upon his glory.” Laughing,Hancock replied, “And it didn’t even stay hid den until the end of this one.”Hancock borrowed Stout’s Jeep and, with out a military guard, returned to First U.S.Army headquarters at Weimar with the threeboxes from the Hohenzollern Museum.After inspecting the contents, Hancock tookthe boxes to the Reichsbank at Frankfurt—this time with an armed escort. Anotherthorough inspection concluded that the ob jects had suffered no damage, and the boxesMonuments Men and Nazi TreasuresThis Prussian crown was part of a collection of coronation paraphernalia found at Bernterode. Below:Two finely wrought swords of Frederick the Great.Fourteen French laborers, former plantworkers, helped move the objects to theelevator shaft. German crews operated theelevators. The cage of the elevator was toosmall for a few of the objects—large paint ings and the caskets—and the engineers hadto make temporary alterations to accommo date them. The last to be hoisted was the cas ket of Frederick the Great, which weighedat least 1,200 pounds and filled the elevator,with not a half-inch to spare.As Frederick the Great’s casket neared thetop of the shaft, a radio in the distance blaredforth the “Star-Spangled Banner,” and justas the coffin came into view, the radio bandstruck up “God Save the King.” It was May8, V-E Day; the war in Europe was over.Captured Nazi DocumentsExamined at Marburg Castlewere repacked and deposited in the bank.The boxes contained, among other objects,the Prussian coronation paraphernalia.Back at Bernterode, Stout was planningthe evacuation of the remaining items in themine. Under the arrangement with the mili tary government and local civilians, powerwas kept up to operate the elevator in themine shaft. Power at the mine, however, wasintermittent and the lighting insufficient.Two shifts of soldiers working daily for threedays packed paintings, flags, and other tex tiles into 180 packages and 40 bundles. Thecaskets were sewn and lashed in carpet wrap ping to facilitate handling and to concealtheir identity.A convoy carried the objects fromBernterode to Marburg, some 100 miles tothe southwest. The military government atMarburg took temporary custody of thebodies and the regimental flags in Schloss(Castle) Marburg, pending their final dispo sition. All other objects were delivered to theJubiläumsbau, or Jubilee Building, which wasthe home of the Kunsthistorisches Museum.Stout noted in his report that althoughthe municipal archives in the mine did notneed to be evacuated immediately, theywould face preservation problems over thenext several months. He also noted the pres ence of explosives in the area of the mine.Hancock suggested the Army consider re moving the flags from Germany.In addition to housing the four caskets andarchives, Marburg Castle became home to aPolitical Document Center, operated by theAmerican State Department and the BritishForeign Office. Throughout May, a collec tion of German Foreign Office documentsfrom other evacuation centers were movedto the castle. There an Anglo-American teamexamined and sorted the documents.The Supreme Headquarters AlliedExpeditionary Forces (SHAEF) directed thePrologue 15

Army Groups to store, safeguard, preserve,and inventory art treasures discovered inareas occupied by their forces. Hancock es tablished the first central collecting point inMarburg in late May 1945.He set up primary operations of the collect ing point in the relatively vacant Staatsarchivbuilding and in the Jubiläumsbau. TheStaatsarchiv building eventually housed paint ings from the Suermondt Museum in Aachen,the Metz Cathedral treasure, and numer ous other cultural properties from Cologne,Essen, and other western German cities.To help Hancock deal with the art, 2ndLt. Sheldon W. Keck (formerly an art con servator at the Brooklyn Museum of Art anda fellow Monuments Man) arrived to pro vide expert care and emergency treatmentfor works of art at Marburg.While Hancock spent most of his timeduring the summer getting the collectingpoint up and running, he found time forthe Bernterode treasure. Hancock had the225 regimental flags transferred from theJubiläumsbau to the castle, where they werestored in the room with the caskets.The treasures stored in the Jubiläumsbauincluded masterpieces from the Berlin Statemuseums. The paintings retrieved from theBernterode mine included two paintings byWatteau that had belonged to Frederick theGreat and other works by Boucher, Chardin,Cranach, Rubens, Van Dyck, Ruysdael, andVan Goyen.On September 15, the Headquarters ofthe Military Government of Land HessenNassau recommended that the regimentalflags be transported to the United States,either as trophies of war or held in custodyfor future disposition. They further recom mended that, “Because of their propagandavalue as symbols of the military tradition,. . . they should not be permitted to remainin Germany. The caskets can be stored in definitely in their present location [inMarburg Castle].”There was similar concern about the royalregalia of Prussia in the Foreign Exchange16 PrologueDepository at Frankfurt. The U.S. GroupControl Council’s MFA&A Branch doubt ed the wisdom of returning the regaliato Potsdam, and they were transferred onSeptember 17 to the Wiesbaden CentralCollecting Point instead.During the last week of the month, allthe paintings recovered at Bernterode, withthe exceptions of the ones that were to beexhibited in Marburg, were moved to theStaatsarchiv as the beginning of a programto consolidate the collecting point underone roof. In the latter part of October, therewas some consideration of moving the battleflags stored in Marburg Castle to the collect ing point, but it was decided that, since theywere trophies of war, they would be keptseparate from the art.Some Artwork is Displayed;Fate of Flags Still UnclearWhen Hancock returned to Marburgin November, after two weeks’ leave, hesaw his long-desired exhibit of German arttake place. Through joint efforts of the staffof the Kunsthistorisches Institut, the rec tor of the university, and the MonumentsMen, the Marburg Central Collecting Pointmounted its first art exhibit, “Masterpiecesof European Paintings.” The exhibit fea tured 30 paintings of very high quality fromamong the artworks found at the Bernterodeand Siegen mines. The exhibit opened inmid-November at the Jubiläumsbau.Keck, the former Brooklyn Museum ofArt conservator, took charge of the MarburgCentral Collecting Point in early November.The transfer of cultural objects from theJubiläumsbau to the Staatsarchiv was com pleted in mid-December.At the same time, the Department of Staterequested that the caskets not be turned over tothe German authorities. State further asked au thorities of the Office of Military Government,U.S. (OMGUS) to arrange for the safekeepingof the caskets for some time to come.The regimental flags, still stored in MarburgCastle, were prepared to be shipped back toWalker K. Hancock, an officer specialist with theMonuments, Fine Arts, and Archives (MFA&A)Section inspected Bernterode on April 29. He reported on the discovery, that officers “entered aroom divided by partitions into a series of compartments, filled with paintings, boxes and tapestries, and hung with brilliant banners.”America as trophies of war and housed at theU.S. Military Academy at West Point. OnDecember 17, however, there was a change ofheart regarding the disposition of the flags bythe MFA&A sections in Seventh Army, andshipment to the United States was postponeduntil further notice.Col. John H. Allen, the chief of theRestitution Branch, wrote to the OMGUSSummer 2013

Monuments Men (from left) George Stout, Sgt. Travese, Walker Hancock, and Steven Kovalyak during theexcavation of Bernterode.chief of staff that the flags appeared to be allof German origin and that the MFA&A officer at the Marburg Central Collecting Pointwas attempting to obtain from scholars a listof exact descriptions of each banner, in thehope that the flags would not have to be unpacked and then repacked before shipment.The chief of staff responded on December20, asking Allen for a more detailed list anddescription of the flags. He stated that it wasdoubtful all of the flags would be sent toWest Point. Some might be turned over tothe French or other Allies, and some, possibly a large part, should be destroyed.A museum expert was found, and he determined that the regimental and battalionflags were all of German origin, with the majority from the 19th and 20th centuries. OnJanuary 3, the collecting point sent OMGUSa list of the flags and recommended that, inview of the artistic and historic significanceof the flags, they be held in custody untiltheir return to the German Government wasdeemed advisable.When it became known that the PoliticalDocuments Unit, and the accompanyingguard, were leaving Marburg Castle, the fourcaskets, flags, and other articles were movedto the Marburg Central Collecting Point atthe Staatsarchiv building on February 8 soMonuments Men and Nazi Treasuresthat they could remain under U.S. militaryguard. The caskets were placed in a locked,fireproof room with barred windows on theground floor.The disposition of the German flags wasstill unsettled. German consultants had recommended that the flags be preserved, especially 14 dating from the 18th century,because of their historical interest and theirartistic value. While awaiting a reply fromWest Point regarding the flags, the OMGfor Greater Hesse reminded OMGUS thatit had 225 military flags and requestedOMGUS make a decision regarding theirdisposition. By early April no decision hadyet been made. Pending a decision, theflags would remain at the Marburg CentralCollecting Point.Finally in May, the Central CollectingPoint sent two shipments to the WiesbadenCentral Collecting Point, which includedthe flags, libraries, paintings, and furniturethat had been recovered at Bernterode.The Four Caskets RemainA Problem for the AmericansAnd what about the caskets?At the State Department, Division ofCentral European Affairs chief James W.Riddleberger and his colleagues talked aboutthe best possible solution for the caskets.Riddleberger believed that if they waited toolong, the reinterment might conceivably become the occasion for some kind of nationalistic demonstration. There was much to besaid in favor of returning the bodies of theHohenzollern rulers to Potsdam, but theyshould be fairly certain of what uses mightbe made of the occasion before proceeding.An alternative would be to ask the government of Greater Hesse to take over the responsibility for a dignified reburial.As for the bodies of the Hindenburgs,Riddleberger advised Ambassador Murphythat the reinterment should be strictly forfamily, “thereby at least symbolically removing the aura of national possession whichthe Nazis attempted to fasten on the oldMarshal.” He added that he did not knowif this idea would be feasible since he hadbeen unable to glean information aboutHindenburgs who still might be alive.Col. John H. Allen, chief of theRestitution Branch, informed Murphy thatthe Marburg Central Collecting Point andall of its German-owned contents housed inthe Staatsarchiv Building were to be turnedover to the appropriate German authorities no later than June 1. He added thatno MFA&A personnel would be stationedin Marburg after this transfer and that thecaskets could not be considered strictly as“cultural objects.” He asked Murphy to advise him what disposition was to be madeof the caskets.Murphy responded to Riddleberger inearly April that the Berlin office had beenseriously considering the problems of thefour caskets. He agreed with Riddleberger’sview that they should rid themselves of theresponsibility before it became a politicalliability. Murphy said they had instituteda search to discover the nearest living relative of the Hindenburgs for a quiet, privatereinterment.As for the two Hohenzollerns, OMGUSfavored the proposal to turn over these bodies, together with those of Hindenburgs ifPrologue 17

George Stout, MFA&A Specialist Officer, reported in May 1945 on the removal of the coffins and other artifacts from the mine and their delivery to the MarburgCollecting Point.no relative could be found, to the GreaterHesse government for simple, dignifiedreburial, devoid of anything resemblinga public demonstration. It would only benecessary, Murphy observed, to state howthe bodies came into U.S. possession. Thedecision not to return the Hohenzollernsto Potsdam could easily be explained by thelack of any central German government ableto take custody.The War Department now had concurredwith the State Department that there shouldbe quiet reinterments of the bodies beforethey became political liabilities.Meanwhile, 62-year-old Oskar vonHindenburg, residing in northern Germanyat Medingen, wrote to the Burgermeister ofMarburg on March 22, stating that he wastrying to locate the coffins of his parents. Hehad received unconfirmed news that theywere supposed to be in Marburg, and heasked if this was correct, adding that the mat ter was of great concern to him. A month lat er, the OMG for Greater Hesse sent the letterto the MFA&A Section, Restitution Branch,which forwarded the correspondence to theOffice of the Political Adviser.“Operation Bodysnatch”Nears an EndingOn May 3 Gen. Lucius Clay, deputy mili tary governor, directed OMG Greater Hesseto turn over the bodies of the Hindenburgsto Oskar von Hindenburg. Hindenburgcould reinter the bodies in either the U.S.or British Zone, but the ceremony mustbe strictly a private family affair with nopublicity.Clay directed that the bodies of the twoHohenzollerns be delivered to the govern ment of Greater Hesse, acting as interimtrustee in absence of any German govern ment. Reinterment in Greater Hesse, hewrote, may be official without being opento the general public, and the OMG forGreater Hesse had to approve the plans.On May 17, the OMG for Greater Hessesummoned the minister president of GreaterHesse, Dr. Karl Geiler, to its headquarters,where he was told to await instructions con cerning the caskets and to be prepared toexecute those instructions as soon as he re ceived them. Before initiating action throughthe German civil government, OMG forGreater Hesse would consult with Wilhelm,the former Crown Prince of Prussia, the cur rent head of the house of Hohenzollern. Thetwo officers who would deal with the fourcaskets were 1st Lt. Theodore A. Heinrich,the MFA&A officer for Kassel, and Capt.Everett P. Lesley, Jr., then with the MFA&Adetachment at Frankfurt. Both had academ ic credentials in art history.Once Lesley became aware of Clay’s in struction, he “immediately dubbed the proj ect Operation Bodysnatch.” Thereafter thecodename “Operation Bodysnatch” was of ten used in official communications.The first two issues relating to OperationBodysnatch were to find places to rebury thecaskets and to inform the Hohenzollern andHindenburg families about the matter. As afirst step, Lesley went to Burg Hohenzollern,Hechingen, Württemberg, in the FrenchZone of Occupation, where former CrownPrince Wilhelm, son of the late Kaiser,was acquainted with the substance of theOMGUS instructions. He concurred in anyfuture steps that might be taken, so long asthese were respectful and observed the req uisite solemnity.Next, the Americans looked for a place tobury the Hohenzollerns. They learned thatthe family owned only two pieces of prop erty in Germany. The first, near Wiesbaden,was deemed unsuitable. The other was BurgHohenzollern, a mountain-peak fairy-talecastle. But the castle was in the FrenchZone. When queried about its possibilityfor the reinterment, the French answer wasunequivocal: they wanted no Hohenzollernsburied in the zone.Then the three explored other possibilitiesin the U.S. Zone without success until theirinvestigation disclosed the Elisabethkirchein Marburg. As the burial place of theLandgraves of Hesse, related by marriageto the Hohenzollerns, it appeared doublyappropriate.The place chosen to bury the twoHohenzollerns was below the floor at the eastside of the north transept, near a medievalTo learn more about The A llies’ discovery of cultural treasures in a German mine after World War II, go to /. Restitution of Nazi looted art, go to /. The discovery of Nazi documents in a cave in Czechoslovakia, go to /.18 PrologueSummer 2013

More than 200 German regimental flags, datingfrom both the early Prussian wars and the WorldWar I era, were hung above the coffins.shrine marking the supposed resting pace ofSt. Elizabeth, a Hohenzollern ancestor. Thenorth transept, cut off from the choir, nave,and crossing by screens and metal gates,could thus be kept closed to public viewwithout arousing curiosity or impairing thefabric of the building.Burial Sites Are FoundBut There Are ProblemsMinister President Geiler was informedof the arrangements for the interment of theHohenzollerns in the Elisabethkirche andwas directed to make arrangements for thetransportation of the caskets and for pro viding simple and dignified markers for thegraves.The two Hohenzollern kings had a fi nal resting place, but where would theHindenburgs be laid to rest?Oskar von Hindenburg was to receivethe bodies of his parents for burial, but inJune, British military government authori ties made it clear that they would opposeany attempt to bury the bodies in the BritishZone of Occupation. In order to avoid in ter-zonal difficulties, and to simplify trans portation concerns, OMG of Greater HesseMonuments Men and Nazi Treasuresdecided to inter the Hindenburg bodies inthe Elisabethkirche as well.Geiler sent von Hindenburg a discreet tele gram inviting him to Wiesbaden to discussa private business matter. On June 12, vonHindenburg was taken to Marburg to viewthe prospective site for his parents’ graves.As the north transept would not read ily accommodate four new graves, and vonHindenburg stated that his father wouldhave considered burial in the company oftwo kings of Prussia to be “ostentatious,” itwas decided that the Hindenburgs shouldbe interred in the chamber (“Turmhalle”) inthe base of the north tower, at the easternend of the church.Von Hindenburg was pleased with thesite, as well as to hear that the state of Hessewould bear most of the costs for reburyinghis parents. “My family,” he said, “is now aspoor as church mice.”During the afternoon, the four cas kets were unwrapped in the MarburgCentral Collecting Point, those of the vonHindenburgs being identified by Oskar vonHindenburg. All caskets were found to bein good condition, though “somewhat bat tered.” The bodies were contained in sealedlead inner coffins, which were not opened.Each of the four gravestones measuredtwo meters by one meter and weighed twotons, sealing the graves and discouraging anyfanatic who might want to steal the bodies.Digging the four graves was not as simplea procedure as first thought. The north tran sept of the Elisabethkirche is built over thesite of an earlier structure, the pilgrimageshrine and tomb of St. Elizabeth of Hungary.Though the remains of St. Elizabeth werethen kept in a shrine in the sacristy, excava tions had to be carried out with care, in caseother relics should be uncovered. The exca vation uncovered masses of bones under theflooring, where none should have been. Thespot had evidently been used for unrecordedburials of pre-Reformation monks attachedto the church. The old bones were carefullymoved over a few feet and reconsecrated.Workers digging under the north towerhit bedrock 24 inches below the floor. Thismeant that the large Hindenburg casketscould not rest beneath the floor as planned.Blasting the bedrock was out of the questiononce someone pointed out that the samedynamiting might bring down the 236-foot14th-century tower.Consequently, a local architect was in structed to raise the church floor in the tow er by several steps so that the large casketscould be accommodated. Carrying out suchextensive alterations within the church whilekeeping their purpose secret, and keepingthe structure open for normal services at thesame time, called for a “maximum of dis simulation” by the various officials.Marburg Operations Closing;Cultural Items Go to WiesbadenWhile Operation Bodysnatch progressed,the Marburg collecting point was clos ing down. The remaining cultural items inthe Staatsarchiv were moved to Wiesbadenin early August. The Wiesbaden CentralCollecting Point now had custody of allthe Bernterode treasure and responsibilityfor its disposition. An unexpected glitch inthe form of a new state secretary arose af ter the June 30 elections. Dr. Hug

and included many from the World War I era. A variety of other cultural items were placed in the room, and the entrances were sealed with brick and mortar on April 2. Oficers with Art Expertise Arrive to Supervise Operations he items were not concealed for long. By the end of